Community Report No. 05

Winter 1999

Caroline Rossi Steinberg, Paul B. Ginsburg, June Eichner

![]() he Lansing health care market has

long been highly concentrated, and has become even more so over the past two years.

Mergers have left only two hospital systems serving the community, and the exit of a

health plan reinforced the strength of the remaining

two plans. These few organizations, along with the community’s three large local

employers, share a

balance of power, while unions and a strong local health department provide a check

on their influence.

he Lansing health care market has

long been highly concentrated, and has become even more so over the past two years.

Mergers have left only two hospital systems serving the community, and the exit of a

health plan reinforced the strength of the remaining

two plans. These few organizations, along with the community’s three large local

employers, share a

balance of power, while unions and a strong local health department provide a check

on their influence.

In 1996, there was tension among these major actors. Purchasers were exerting pressure to lower health care costs, and a proposed merger of a local hospital with Columbia/HCA was widely divisive. Key developments since 1996 include:

- Recent Hospital Mergers Intensify Competition

- Sparrow-St. Lawrence Merger

- IRMC-McLaren Merger

- Physician Efforts to Exert Power Resisted

- New PPO Gains Market Share

- Purchaser Alliance Regroups and Refocuses

- Information Provides Mechanism for Accountability

- Collaborative Community Efforts Led by Health Department

- Problems Looming for Mandatory Medicaid Managed Care

- Issues to Track

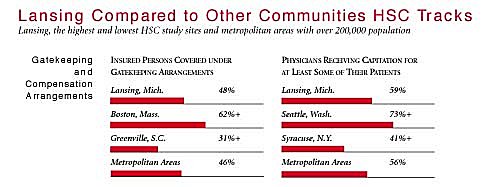

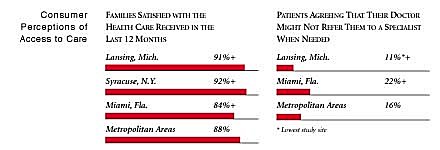

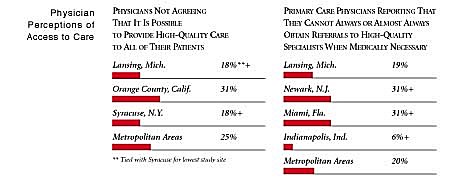

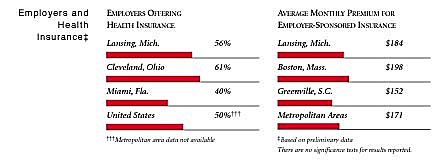

- Lansing Compared to Other Communities HSC Tracks

- Background and Observations

![]() wo mergers took place in the Lansing

market since HSC’s site visit in 1996,

leaving only two hospital systems in

the area. The Sparrow Health System-

St. Lawrence Hospital merger in late 1997 brought together two local entities.

After a failed merger attempt with Columbia/ HCA, Ingham Regional Medical Center

(IRMC) merged with a regional system, the McLaren Health Care Corporation based in

Flint. These mergers have left two financially strong competitors, reduced inpatient

capacity and more starkly defined competition.

wo mergers took place in the Lansing

market since HSC’s site visit in 1996,

leaving only two hospital systems in

the area. The Sparrow Health System-

St. Lawrence Hospital merger in late 1997 brought together two local entities.

After a failed merger attempt with Columbia/ HCA, Ingham Regional Medical Center

(IRMC) merged with a regional system, the McLaren Health Care Corporation based in

Flint. These mergers have left two financially strong competitors, reduced inpatient

capacity and more starkly defined competition.

![]() n 1996, St. Lawrence was experiencing

financial difficulties, and its physical

plant was deteriorating due to lack of capital investment. Given overcapacity

in Lansing hospitals in general and a declining patient census at St. Lawrence, it did

not make sense to invest in much-needed upgrades. Its parent, Mercy Health Services,

wanted to maintain a Catholic presence in the market and had been exploring partnership

opportunities for St. Lawrence with Sparrow and

IRMC for some time. An arrangement with Sparrow, the stronger of the two, appeared to

offer the best option.

n 1996, St. Lawrence was experiencing

financial difficulties, and its physical

plant was deteriorating due to lack of capital investment. Given overcapacity

in Lansing hospitals in general and a declining patient census at St. Lawrence, it did

not make sense to invest in much-needed upgrades. Its parent, Mercy Health Services,

wanted to maintain a Catholic presence in the market and had been exploring partnership

opportunities for St. Lawrence with Sparrow and

IRMC for some time. An arrangement with Sparrow, the stronger of the two, appeared to

offer the best option.

St. Lawrence’s strengths-behavioral health and aging services and its west side location - complemented Sparrow’s services and geographic market. The Sparrow-St. Lawrence merger was predicted in 1996 and is widely viewed as successful. Most St. Lawrence physicians reportedly have moved to Sparrow, where many already had privileges, although some chose to practice with the competing hospital system, IRMC. St. Lawrence has closed its inpatient medical and surgical services, but still operates an emergency room and maintains beds for psychiatric, substance abuse and hospice services. Community inpatient capacity is now somewhat stretched, and both Sparrow and IRMC have had to close their emergency rooms to nontrauma cases at different times because their inpatient beds were full. However, hospital respondents claim that reduced capacity has lowered costs for inpatient care.

![]() n 1996, IRMC was still working

through the merger that had formed it several years earlier. While it operated in

the black, it needed capital for facility upgrades to consolidate services and

benefit more effectively from the merger. IRMC initially chose to pursue a

partnership with Columbia/HCA, which would have brought the first for-profit

general acute care hospital to Michigan.

n 1996, IRMC was still working

through the merger that had formed it several years earlier. While it operated in

the black, it needed capital for facility upgrades to consolidate services and

benefit more effectively from the merger. IRMC initially chose to pursue a

partnership with Columbia/HCA, which would have brought the first for-profit

general acute care hospital to Michigan.

While the Capital Area Health Alliance (CAHA), which at the time represented primarily the business community, initially supported the deal, four key market leaders - the United Auto Workers (UAW) and later General Motors (GM), Sparrow and Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Michigan (BCBSM) - opposed it. There was significant press coverage and public concern about the potential impact of this merger on IRMC’s accountability to the community. Ultimately, the state Attorney General sued, and a Michigan state court ruled that it was illegal to comingle assets from a not-for-profit and a for-profit entity, thus preventing the merger as structured from proceeding.

BCBSM reportedly suggested several alternative partners for IRMC, including the not-for-profit McLaren, which was trying to develop a regional presence and which offered access to capital for IRMC. An affiliation agreement was reached in 1997 that made IRMC a wholly owned subsidiary of McLaren. Community response to this relationship has been favorable. IRMC has since improved its financial performance, increased market share and made significant capital improvements.

Since the mergers, competition between the two hospital systems has reportedly increased, even though both are operating at high occupancy levels because of reduced hospital capacity overall. Physicians report increased hospital efforts to align them to one hospital or the other through physician-hospital organizations. This trend may intensify if the hospital systems move forward with plans to develop exclusive products. Currently, both systems are exploring this option. The Sparrow-owned Physicians Health Plan (PHP) is considering offering Sparrow-only products, and McLaren is working on developing an exclusive network product through an arrangement with BCBSM.

![]() hysicians have been uneasy

about the concentration and power of Lansing

hospitals and health plans, but efforts to establish their own base have been

largely unsuccessful. At the time of the first site visit, several physician

entrepreneurs

were opening ambulatory surgery centers.

GM views these facilities as duplicative of hospital capacity rather than as

desirable competition and does not allow its health plans to include them in

their networks. Meanwhile, the major plans have refused to contract with them,

with the exception of PHP, which contracts with a center owned by Sparrow. As a

result, the centers have been cut off from most of Lansing’s privately insured

patients.

hysicians have been uneasy

about the concentration and power of Lansing

hospitals and health plans, but efforts to establish their own base have been

largely unsuccessful. At the time of the first site visit, several physician

entrepreneurs

were opening ambulatory surgery centers.

GM views these facilities as duplicative of hospital capacity rather than as

desirable competition and does not allow its health plans to include them in

their networks. Meanwhile, the major plans have refused to contract with them,

with the exception of PHP, which contracts with a center owned by Sparrow. As a

result, the centers have been cut off from most of Lansing’s privately insured

patients.

In 1997, the Thoracic Cardiovascular Institute (TCI), a group of thoracic and vascular surgeons and cardiologists, negotiated a contract with Blue Care Network (BCN) to be the exclusive provider of cardiovascular care under a capitated arrangement. This would have given TCI significant control over payment for these services, putting the hospitals and supporting specialists in the position of negotiating rates with TCI rather than BCN. Sparrow and a group of competing specialists reportedly fought the deal, and new management at BCN withdrew from the contract. Had the contract gone through as originally structured it would have been the first of its type in the Lansing market.

Against a backdrop of these unsuccessful entrepreneurial ventures, physicians are adopting a defensive strategy of consolidating into larger group practices in an effort to counteract growing polarization of the market around the two hospital systems. To ensure continued patient flow if more exclusive network arrangements take hold, physicians want to have colleagues in their practices who can admit patients to both hospitals. As one physician said, "I could wake up tomorrow and find that Michigan State University [MSU] has shifted its entire enrollment to a different plan and that I have lost half my patients."

![]() ell-connected to auto manufacturers

and the UAW, BCBSM has a stable and strong position in Lansing, controlling well over

half of the commercially

insured market in the state. Until

recently it had not been known as an innovator. However, the introduction

of Community Blue, a preferred provider organization (PPO), indicates change,

as it is a competitive move to shift

enrollment from BCBSM’s basic fee-

for-service product to one that is

relatively unrestricted and significantly less expensive. The PPO offers a broad

network, an out-of-network option

and increased access to preventive

services compared to the traditional product. BCBSM is able to offer the PPO at a

lower cost because it pays hospitals managed care contract rates rather than rates

used for traditional products.

ell-connected to auto manufacturers

and the UAW, BCBSM has a stable and strong position in Lansing, controlling well over

half of the commercially

insured market in the state. Until

recently it had not been known as an innovator. However, the introduction

of Community Blue, a preferred provider organization (PPO), indicates change,

as it is a competitive move to shift

enrollment from BCBSM’s basic fee-

for-service product to one that is

relatively unrestricted and significantly less expensive. The PPO offers a broad

network, an out-of-network option

and increased access to preventive

services compared to the traditional product. BCBSM is able to offer the PPO at a

lower cost because it pays hospitals managed care contract rates rather than rates

used for traditional products.

Early indications are that Community Blue will further bolster BCBSM’s position in the Lansing market. It is taking business away from PHP and the Blues’ own HMO subsidiary, BCN. Community Blue premiums are below BCBSM’s traditional and HMO products, and in 1998, MSU converted all of its non-Medicare enrollment in its Blues’ traditional and HMO plans to Community Blue. PHP lost enrollment to Community Blue as well, and was forced to lower its rates to remain competitive. Several other purchasers, including the Chamber of Commerce - the exclusive sponsor of Blues’ products for small employers - have converted to Community Blue.

As a result of the success of Community Blue, BCBSM has been able to convert large blocks of business to the lower hospital rates without negotiating with the hospitals. Because they are receiving less money for the same population, hospitals are seeking recourse through the state hospital association.

![]() n 1996, purchasers seemed poised to

play a more active leadership role in

the Lansing market through CAHA, the

local health care coalition. The three large employers in the area - GM, MSU and

the state - had joined with local providers and other health care stakeholders to

reduce costs and monitor quality. The coalition became strained when its purchaser

members began to exert pressure on local providers to drive down costs.

n 1996, purchasers seemed poised to

play a more active leadership role in

the Lansing market through CAHA, the

local health care coalition. The three large employers in the area - GM, MSU and

the state - had joined with local providers and other health care stakeholders to

reduce costs and monitor quality. The coalition became strained when its purchaser

members began to exert pressure on local providers to drive down costs.

As a result, CAHA nearly disbanded before reorganizing and changing its focus to public health goals, including promoting wellness and supporting universal access to health care. CAHA has expanded from 70 to 108 members and has given seats on its board to the Ingham County Health Department, health plans and unions. The state has pulled out of CAHA, and the three large employers are pursuing their cost and quality objectives apart from this venue, with the state and the university working together and GM working independently.

One issue that all of the constituencies represented in CAHA can organize around is saving GM. According to news reports, the automobile company is considering whether to rebuild its outdated plants in Lansing or relocate them elsewhere. This decision puts at risk 13,000 GM jobs and an estimated 21,000 supporting jobs in Lansing. Demonstrating that Lansing is a good place to do business, which includes being a low-cost health care market, is a major element in the save-GM strategy.

![]() nformation continues to provide a

way to hold Lansing health system organizations accountable to standards of cost,

quality and community benefit. Efforts

to report such information to the public have been controversial, so many of the

data produced recently have been for internal use by hospitals, physician groups,

plans and purchasers. The

impact of this change on community accountability remains to be seen.

nformation continues to provide a

way to hold Lansing health system organizations accountable to standards of cost,

quality and community benefit. Efforts

to report such information to the public have been controversial, so many of the

data produced recently have been for internal use by hospitals, physician groups,

plans and purchasers. The

impact of this change on community accountability remains to be seen.

In 1996, the three large employers had a number of initiatives underway to gather and compare information across hospitals through claims data analysis. These led to a reduction in hospital rates in Lansing and were the genesis of additional efforts to look at cost and quality indicators across the hospitals.

Just after the 1996 site visit, the three large employers uncovered a substantial payment differential in what BCBSM paid the two hospital systems, with Sparrow’s rates significantly higher than those of IRMC. Public release of this information was controversial and led to a reduction in hospital reimbursement and premium levels for BCBSM across the market. Sparrow objected to the process and outcome of this effort and has become mistrustful of additional collaborative information initiatives.

CAHA’s subsequent effort to collect data on cost and quality heightened hospital concerns that the data could not be adequately risk-adjusted and represented only a limited patient base. As in many markets, providers are not convinced that cost and quality information can be conveyed fairly and accurately to the public.

Since that time, the hospitals have begun to produce their own data using a medical record-based system instead of one that was claims-based, to improve data accuracy and allow for risk-adjustment. The three large employers and the hospitals have been sharing information among themselves, but are not releasing it to the public.

No longer working together, each of the large purchasers is using data for its own purposes. The state and MSU have been analyzing claims data and are meeting with the hospitals individually to discuss the results; GM is using a health plan report card for internal scoring of plans, a system that may be adopted by Medicaid. But since these comparative data are no longer publicly available, smaller employers do not have access to them to inform their purchasing decisions.

Efforts to release data have also been pursued for the noncommercial population. Shortly after HSC’s first site visit, the Ingham County Health Department released data showing that the level of indigent care that IRMC was providing was low in proportion to its overall market share. The report sparked controversy and ongoing disagreement on the methodology for calculating more broadly how hospitals provide benefit to the community. This issue still has not been resolved locally.

![]() he Ingham County Health Department

continues to identify public health and indigent care issues and to play a critical

role in bringing together health system and business leaders in the community

to address them. Several initiatives to increase access are underway, and Lansing’s

mayor is playing an active

role in these efforts, despite the city’s

lack of jurisdiction over health care.

he Ingham County Health Department

continues to identify public health and indigent care issues and to play a critical

role in bringing together health system and business leaders in the community

to address them. Several initiatives to increase access are underway, and Lansing’s

mayor is playing an active

role in these efforts, despite the city’s

lack of jurisdiction over health care.

Key among these initiatives is the newly implemented Ingham Health Plan, a program to provide coverage for the uninsured. The program taps into federal Medicaid matching dollars, bringing $1.8 million of new funding into the community to provide coordinated preventive, primary, specialty and ancillary care to about 7,500 uninsured individuals with income levels up to 140 percent of poverty level. Although the program does not cover inpatient care, funding flows through the hospitals as a disproportionate share payment. However, Sparrow has elected not to participate, which has reduced access to federal funding and limited the program’s capacity. According to the county health department, if Sparrow were to participate, the program would be able to get an additional $1.6 million in federal funding and extend coverage to 3,500 more individuals.

To build on this program, the health department has also taken the lead in securing funding from The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the W. K. Kellogg Foundation for two initiatives to increase access to the uninsured. Access to Health will bring together local hospital systems, the business community, insurers and consumers to assess the needs of the uninsured and recommend ways to finance and deliver care to this population. Ingham Community Voices will provide funding to conduct outreach and develop an information system to support this effort.

![]() nrollment in mandatory Medicaid

managed care was scheduled to be complete in the Lansing area by January 1999, but

health plans are having difficulty managing the Medicaid population, and there is

some question about whether

the plans will continue to offer Medicaid managed care products. Three plans

currently enroll Medicaid beneficiaries

in Lansing: PHP, The Wellness Plan

and the McLaren Medicaid plan. Care Choices, the Mercy plan, agreed to exit the

Medicaid market in Lansing as part

of the Sparrow-St. Lawrence merger. Despite losses in 1997, the other plans have

not dropped out.

nrollment in mandatory Medicaid

managed care was scheduled to be complete in the Lansing area by January 1999, but

health plans are having difficulty managing the Medicaid population, and there is

some question about whether

the plans will continue to offer Medicaid managed care products. Three plans

currently enroll Medicaid beneficiaries

in Lansing: PHP, The Wellness Plan

and the McLaren Medicaid plan. Care Choices, the Mercy plan, agreed to exit the

Medicaid market in Lansing as part

of the Sparrow-St. Lawrence merger. Despite losses in 1997, the other plans have

not dropped out.

Specific issues that plans have encountered in the Medicaid market include:

The Medicaid contracts run through 1999, but the minority-owned Wellness Plan is experiencing severe difficulty, and PHP has indicated it may drop its Medicaid product if it operates at a loss. The state is working with The Wellness Plan to keep it operating. If these two plans pull out, it is unlikely that the state will have sufficient capacity to support Medicaid managed care in Ingham County.

![]() he Lansing market continues to be

dominated by a few large, powerful local organizations. Hospital mergers have

created two strong players and polarized the market, and competition appears to be

increasing. Unable to exert power effectively, physicians are organizing defensively

so they can care for their patients in either existing hospital. The county health

department continues to play a leadership role in expanding

access for the uninsured.

he Lansing market continues to be

dominated by a few large, powerful local organizations. Hospital mergers have

created two strong players and polarized the market, and competition appears to be

increasing. Unable to exert power effectively, physicians are organizing defensively

so they can care for their patients in either existing hospital. The county health

department continues to play a leadership role in expanding

access for the uninsured.

As the market continues to evolve, several key issues bear watching:

Lansing, the highest and lowest HSC study sites and metropolitan areas with over 200,000 population

+Site value is significantly different from the mean for metropolitan areas over 200,000

population.

The information in these graphs comes from the Household, Physician and Employer

Surveys conducted in 1996 and 1997 as part of HSC’s Community Tracking Study. The

margins of error depend on the community and survey question and include +/- 2

percent to +/- 5 percent for the Household Survey, +/-3 percent to +/-9 percent

for the Physician Survey and +/-4 percent to +/-8 percent for the Employer Survey.

| Lansing, Mich. | Metropolitan areas above 200,000 population | |

| Population, 19971 | ||

| 447,349 | ||

| Population Change, 1990-19971 | ||

| 3.2% | 6.7% | |

| Median Income2 | ||

| $29,999 | $26,646 | |

| Persons Living in Poverty2 | ||

| 11% | 15% | |

| Persons Age 65 or Older2 | ||

| 9.8% | 12% | |

| Persons with No Health Insurance2 | ||

| 8.3% | 14% | |

|

Sources: 1. U.S. Census, 1997 2. Household Survey Community Tracking Study, 1996-1997 | ||

The Community Tracking Study, the major effort of HSC, tracks changes in the health system in 60 sites that are representative of the nation. Every two years, HSC conducts surveys in all 60 communities and site visits in the following 12 communities: