Issue Brief No. 124

October 2008

Debra A. Draper, Laurie E. Felland, Allison Liebhaber, Johanna Lauer

Passage of health reform legislation in Massachusetts required significant bipartisan compromise and buy in among key stakeholders, including employers. However, findings from a recent follow-up study by the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC) suggest two important developments may threaten employer support as the reform plays out. First, improved access to the nongroup—or individual—insurance market, the availability of state-subsidized coverage, and the costs of increased employee take up of employer-sponsored coverage and rising premiums potentially weaken employers’ motivation and ability to provide coverage. Second, employer frustration appears to be growing as the state increases employer responsibilities. While the number of uninsured people has declined significantly, the high cost of the reform has prompted the state to seek additional financial support from stakeholders, including employers. Improving access to health care coverage has been a clear emphasis of the reform, but little has been done to address escalating health care costs. Yet, both must be addressed, otherwise long-term viability of Massachusetts’ coverage initiative is questionable.

![]() assachusetts health care reform to attain near-universal

health insurance coverage has been widely heralded as successful in improving

residents’ access to coverage. Since the reform became law in 2006, 439,000

people have gained coverage—many more than the 379,000 people the state

initially estimated as being uninsured.1 As a result, the

state’s rate of uninsured working-age adults has dropped significantly, decreasing

from 13 percent to 7 percent.2

assachusetts health care reform to attain near-universal

health insurance coverage has been widely heralded as successful in improving

residents’ access to coverage. Since the reform became law in 2006, 439,000

people have gained coverage—many more than the 379,000 people the state

initially estimated as being uninsured.1 As a result, the

state’s rate of uninsured working-age adults has dropped significantly, decreasing

from 13 percent to 7 percent.2

A hallmark of the reform is the individual mandate, which emphasizes individual responsibility for obtaining health insurance coverage. Under the individual mandate, uninsured adults who the state has deemed able to afford coverage face a tax penalty. Although many residents complied with the mandate, approximately 62,000 taxpayers were deemed unable to afford even the lowest cost insurance in 2007; an additional 86,000 taxpayers went without insurance and were assessed the tax penalty of approximately $200.3

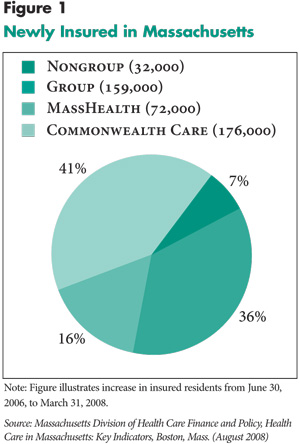

The majority of newly insured residents—57 percent—obtained either free coverage through the state’s Medicaid program (MassHealth) or subsidized coverage through the Commonwealth Care program (see Figure 1). The high cost of these programs has prompted the state to seek additional financial support. A critical funding source for the reform is a Medicaid waiver, which the federal government recently renewed, generating $21.2 billion over three years. The renewal includes a $4.3 billion increase over the next three years, which reflects in part the heavy demand for state-supported coverage and the high costs of those programs. Beginning July 2008, the state also increased tobacco taxes by $1 per pack, which is expected to raise $174 million in new funding.4 Moreover, the state passed a supplemental appropriations bill in July 2008 to provide $89 million in additional funding, including assessments and fees levied on health plans and providers.

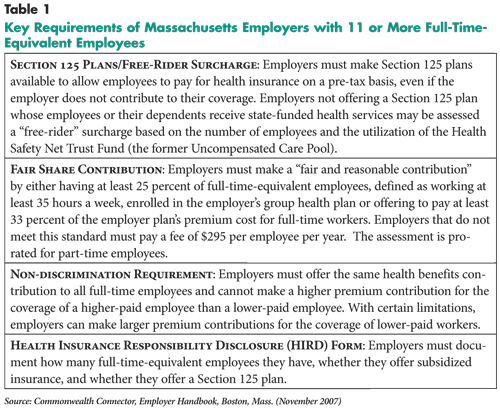

The state continues to look to another important stakeholder group—employers—to ramp up their commitment to the reform. Employer support was key to passing the legislation. A previous reform effort in the 1980s was not implemented because of employer resistance to an employer coverage mandate, so premising the reform as an individual mandate went a long way toward gaining employer support. Along with the individual mandate, however, there are specific requirements of employers with 11 or more full-time-equivalent employees that aim to increase the overall accessibility of coverage for residents, as well as help fund state coverage programs for low-income residents (see Table 1).

Employers are required to set up Section 125, or cafeteria, plans to allow employees to purchase health insurance with pre-tax dollars, and employers that do not meet this requirement may be subject to a “free-rider” surcharge if their employees’ or dependants’ care is paid for by the state’s Health Safety Net Trust Fund (the former Uncompensated Care Pool). In addition, employers that do not offer a “fair and reasonable” contribution for their employees’ coverage are assessed up to $295 per worker per year, which is intended to help equalize the uncompensated care burden among all employers. As the reform moves forward, these requirements continue to expand.

HSC researchers recently conducted a follow-up site visit to Massachusetts to explore the impact of the state’s reform effort on employers more than a year into its implementation (see Data Source). A previous site visit in 2007 examined how employers were preparing for the reform’s implementation.5 While employer support for the reform has been relatively strong to date, findings from the recent follow-up site visit suggest two potential changes that may threaten employers’ continued support. First, higher costs from increased take up of employer-sponsored coverage and rising premiums, coupled with improved access to the nongroup, or individual, insurance market, potentially weaken employers’ motivation and ability to provide coverage. Second, employer frustration appears to be growing as the state pressures them to increase their responsibilities.

|

|

![]() lthough the state has made significant progress in reducing

the number of uninsured people through state-supported coverage programs, increased

take up of employer-sponsored coverage also has played a major role in reducing

the number of uninsured. Nearly 160,000 newly insured residents—36 percent

of the total—complied with the individual mandate by obtaining coverage

through their employer. Respondents largely attributed the increase in coverage

to higher take up by workers of existing employer offers of coverage.

lthough the state has made significant progress in reducing

the number of uninsured people through state-supported coverage programs, increased

take up of employer-sponsored coverage also has played a major role in reducing

the number of uninsured. Nearly 160,000 newly insured residents—36 percent

of the total—complied with the individual mandate by obtaining coverage

through their employer. Respondents largely attributed the increase in coverage

to higher take up by workers of existing employer offers of coverage.

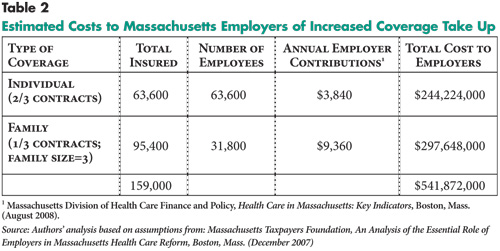

The cost to employers of the additional coverage take up is substantial. Based on similar assumptions previously used by the Massachusetts Taxpayers Foundation, a ballpark estimate of the increased costs to employers is about $540 million (see Table 2). Costs are likely to increase as more residents are expected to take up employer coverage to avoid the tax penalty, which will be significantly higher for 2008 at half the annual premium of the lowest cost health plan available. For an adult making approximately $31,000 a year, the penalty would be about $900.6

In addition to the cost pressures created by the increased take up of coverage, Massachusetts employers continue to experience large premium increases, which for some small employers are reportedly in the double digits. Respondents largely attributed rising premiums to the escalating costs of Massachusetts’ characteristically expensive health care system. Many expressed concern that unless the state seriously addresses the underlying factors driving costs, the current trajectory of the reform is financially unsustainable.

The Massachusetts Health Care Quality and Cost Council was created by the reform law to develop quality improvement and cost-containment goals and strategies. However, its start up has been slow, and many expressed disappointment that more progress has not been made. As one respondent commented, “I would say there isn’t a lot concrete to point to. They have set up rigorous goals for themselves, now we’ll see whether they can achieve them.” But given the state’s difficulty in controlling health care costs, premiums are likely to continue to escalate, at least in the near term.

|

![]() ccess to individual coverage has markedly improved under the reform. While this is a positive outcome, it also has the potential to weaken employers’ motivation to offer coverage, particularly employers with many low-wage workers or who are not already offering coverage. Approximately 32,000 of the newly insured—7 percent of the total—purchased individual, non-subsidized coverage either through private insurers or the Commonwealth Health Insurance Connector Authority, known as the Connector, the independent public agency responsible for administering key components of the reform, including the Commonwealth Choice program.

ccess to individual coverage has markedly improved under the reform. While this is a positive outcome, it also has the potential to weaken employers’ motivation to offer coverage, particularly employers with many low-wage workers or who are not already offering coverage. Approximately 32,000 of the newly insured—7 percent of the total—purchased individual, non-subsidized coverage either through private insurers or the Commonwealth Health Insurance Connector Authority, known as the Connector, the independent public agency responsible for administering key components of the reform, including the Commonwealth Choice program.

An important strategy to improve access to individual coverage was the merger of the small group (750,000 individuals) and nongroup (50,000 individuals) markets to pool the health care risks. Prior to the reform, the nongroup market offered the protections of modified community rating, allowing premiums to vary only by age, geography and family size but not by gender or health status. Adverse risk selection plagued the nongroup market as older, less-healthy people were more likely to purchase individual coverage. Because few people could afford the high premiums caused by this market dynamic, few insurers offered individual insurance products. The merger of the markets was expected to reduce nongroup premiums by approximately 15 percent and raise small group premiums slightly.7 To date, however, nongroup premiums have declined more than expected. For example, the Connector reported that premiums for a 37-year-old purchasing individual coverage declined by as much as 50 percent.

The availability of individual insurance products through the Commonwealth Choice program also has made it much easier for residents to shop for coverage. Residents can choose from an array of products offered by six different insurers. About 18,000 newly insured residents with individual coverage, or 60 percent, purchased it through the Connector.8 This includes 4,000 young adults (ages 19-26) who purchased insurance products tailored to their age group offered exclusively through the Connector. The Connector also was expected to provide a marketplace for small employers to purchase coverage but implementation has been delayed. Several respondents suggested that the delay may have resulted in missed opportunities for the Connector to engage employers, particularly small employers, that have not previously offered coverage to begin doing so.

Additionally, more individuals are now able to purchase nongroup coverage using pre-tax dollars under the reform’s requirement that employers make available Section 125, or cafeteria, plans. This option saves employees an average of 41 percent—although it varies depending on an individual’s tax bracket—on insurance premiums without direct involvement from the employer.9 Employees’ reduced taxable income also reduces payroll taxes for the employer. Respondents reported that the burden of setting up a Section 125 plan is not particularly onerous, and employers can obtain assistance from a variety of sources, including the Connector, business groups and insurers. As of July 2008, the Connector reported setting up these plans for more than 3,000 employers with approximately 1,000 employees purchasing coverage using this mechanism.

State-subsidized coverage also may weaken some employers’ motivation to offer coverage—especially those with many low-wage workers—because in the absence of an employer offering coverage, low-wage employees may be eligible for subsidized coverage through Commonwealth Care. Currently, if individuals are eligible for and offered coverage through their employer, they are ineligible for state-subsidized coverage. The reform has safeguards against crowd out—a substitution of public coverage for employer-sponsored coverage—by setting Commonwealth Care’s premium contributions and patient cost sharing at levels approximate to employer-sponsored coverage. Consideration is being given to allow low-wage workers who cannot afford to take up their employers’ insurance to instead obtain coverage through Commonwealth Care. However, some respondents expected the contemplated change would generate significant crowd out over time, resulting in considerably higher costs to the state.

While it is too early to determine whether employers’ motivation to offer coverage will weaken to the point of their dropping coverage, there is at least a preliminary report of a slight enrollment decline in the small group market. According to the Massachusetts Association of Health Plans, small group enrollment declined by about 15,000 individuals in 2007 despite an overall increase in the take up of employer-sponsored coverage. However, most respondents expected that large employers’ commitment to offering coverage will remain largely unchanged in the near future, but small employers’ interest and ability to continue administering health benefits may be waning and hastened by the economic downturn. As one broker remarked, “I think for employers, they’re getting more involved [in health benefits] than they ever meant to be. They’re trying to find ways to distance themselves.”

![]() he absence of an employer mandate in the reform legislation went a long way toward gaining employer support. Yet, respondents of several small business groups were skeptical of the reform from the beginning, given key questions left unanswered by the legislation and the wide discretion left to state regulatory agencies and to the Connector to establish specific requirements. At the time, however, they thought it politically inadvisable to voice opposition, which as one respondent said, “To challenge the law would be a challenge to the political structure, and that gives pause to a lot of people.” Also, given the disparate stakeholders involved and the national attention focused on the reform, there was considerable pressure on employers to cooperate. But now that dynamic may change as employers face expanding requirements. As one respondent observed, “The recent proposals for new assessments and triggers are starting to really cause major faults in the business community’s support.”

he absence of an employer mandate in the reform legislation went a long way toward gaining employer support. Yet, respondents of several small business groups were skeptical of the reform from the beginning, given key questions left unanswered by the legislation and the wide discretion left to state regulatory agencies and to the Connector to establish specific requirements. At the time, however, they thought it politically inadvisable to voice opposition, which as one respondent said, “To challenge the law would be a challenge to the political structure, and that gives pause to a lot of people.” Also, given the disparate stakeholders involved and the national attention focused on the reform, there was considerable pressure on employers to cooperate. But now that dynamic may change as employers face expanding requirements. As one respondent observed, “The recent proposals for new assessments and triggers are starting to really cause major faults in the business community’s support.”

The inclusion of prescription drug coverage in the minimum creditable coverage requirements established by the Connector Board has particularly irritated employers. Effective Jan. 1, 2009, individuals are required to have prescription drug coverage to meet the individual mandate and avoid the tax penalty. Although employers are not directly affected by the requirements, respondents expected employers to be pressured to provide coverage that meets the requirements. Otherwise, employees will be required to obtain additional coverage or pay the tax penalty because their coverage does not meet the minimum standard. The Massachusetts Taxpayers Foundation has estimated that approximately 163,000 insured residents do not have prescription drug coverage, and of these, more than 80 percent have employer-sponsored coverage. According to the foundation, the additional cost to employers of adding prescription drug coverage is estimated at $24 million.

Given the high costs of the reform, many respondents expressed dismay at what they perceived as the “richness” of the benefit requirements, believing the requirements fuel cost pressures and make affordable coverage even less attainable. As one respondent stated, “If the choice is between comprehensive and cost, comprehensive wins every time.”

Other recent developments also have frustrated employers and led to some pushback. Effective Jan. 1, 2009, for example, the state plans to implement a change in the standards for defining a “fair and reasonable” contribution to employees’ health care costs, requiring employers with more than 50 full-time-equivalent employees to meet both thresholds (33 percent premium contribution and 25 percent employee take up). Initially, the state proposed that employers with 11 or more employees be subject to the more stringent criteria. Among the concerns of the employer community was that small employers, those with fewer than 50 employees, would be disproportionately affected by the change. The state compromised and excluded these small employers from the additional requirement. The state also agreed to allow employers with 75 percent or greater take up among full-time employees to pass the fair share test, regardless of their rate of contribution. Under the change, the state estimates that approximately 1,100 employers will be required to pay the fair share assessment and expects to raise about $30 million annually, nearly four times more than previously collected.

The state also is changing the fair share filing requirements. Instead of an annual filing, employers will now be required to file on a quarterly basis. Several respondents discussed that the more frequent filings create additional burden and have contributed to growing employer frustration.

As responsibilities increase and affect a broader set of employers, including those already offering coverage, it raises an important question about whether the reform is evolving into an employer mandate. Federal Employee Retirement Income and Security Act (ERISA) regulations effectively pre-empt self-funded employer health plans from state laws governing health insurance, including state coverage mandates. Some respondents were surprised that an ERISA challenge to the reform law has not been attempted in Massachusetts, with a successful legal challenge potentially undoing important reform components.

![]() assachusetts has made remarkable progress in improving access to health care coverage for residents, and, as a result, the number of uninsured residents has significantly declined. But almost two years into the reform, Massachusetts has done little to address rising health care costs.

assachusetts has made remarkable progress in improving access to health care coverage for residents, and, as a result, the number of uninsured residents has significantly declined. But almost two years into the reform, Massachusetts has done little to address rising health care costs.

While the reform was premised on individual responsibility, the reality is that individuals have limited wherewithal to do more, especially considering that nearly 60 percent of the newly insured gained coverage through state-supported programs. As the economy declines, cost pressures on the state may increase to the extent that more individuals seek subsidized coverage. Consequently, other stakeholders—health plans, providers and employers—will assuredly be called upon to assume greater responsibility. Yet, additional levies on health plans and providers are likely to be passed on to employers through higher premiums. So, ultimately, it may be employers who are expected to shoulder a large share of the burden.

Employers offer health coverage to attract and retain a qualified and productive workforce. But this is a voluntary employer activity, and if the reform plays out in a way they perceive as disadvantageous, they may push back and seek judicial or other remedies. This may be especially pertinent for employers offering coverage, but whose workers face tax penalties because the coverage offered does not meet state requirements. Other employers, especially small employers that are financially vulnerable, may decide that the requirements associated with offering their employees coverage are onerous or costly compared to the benefits, and may opt instead to forgo providing coverage. Moreover, it is unlikely that employers not offering coverage would be encouraged to do so if they perceive the required responsibilities as financially or administratively burdensome.

In its efforts to attain near-universal coverage for residents, Massachusetts has clearly focused on improving access to health care coverage rather than on controlling costs. Yet, long-term sustainability requires both be addressed in tandem. Absent credible cost-containment efforts, health care costs will continue to escalate, which may ultimately prove to be the undoing of Massachusetts’ historic coverage initiative.

In 2008 HSC conducted a follow-up site visit to Massachusetts to study the

impact in the second year of the state’s health reform law on employers.

The first site visit was conducted in January 2007, and the findings were disseminated

through an HSC Issue Brief in July 2007. Between May and August 2008, HSC researchers

interviewed 28 key stakeholders, including representatives of employer groups,

benefits consultants, brokers, health plans, providers, policy makers, advocates

and other knowledgeable observers to obtain their perspectives on how the reform

is progressing and its impact on employers. A two-person research team conducted

each interview, and notes were transcribed and jointly reviewed for quality

and validation purposes. The interview responses were coded and analyzed using

Atlas.ti, a qualitative software tool.

ISSUE BRIEFS are published by the

Center for Studying Health System Change.

600 Maryland Avenue, SW, Suite 550

Washington, DC 20024-2512

Tel: (202) 484-5261

Fax: (202) 484-9258

www.hschange.org