Tracking Report No. 23

March 2009

James D. Reschovsky, Laurie E. Felland

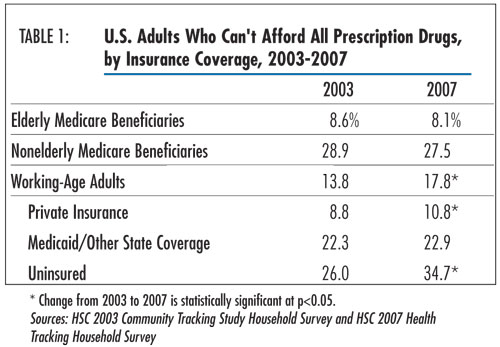

Despite the introduction of a Medicare outpatient prescription drug benefit in January 2006, roughly the same proportion of elderly Medicare beneficiaries in 2003 and 2007—about 8 percent—skipped filling at least one prescription drug because of cost concerns, according to a new national study by the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC). However, over the same period, more working-age adults went without a prescribed drug because of cost, suggesting the new Medicare drug benefit may have prevented a similar deterioration in access for the elderly. But, the proportion of seniors dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid who went without a prescribed medicine almost doubled between 2003 and 2007—from 10.8 percent to 21.3 percent. And, the new Medicare drug benefit did little to close large, longstanding prescription drug access gaps between elderly white and African-American beneficiaries, healthier and sicker beneficiaries, and lower-income and higher-income beneficiaries. For example, three times as many elderly African-American beneficiaries (17.6%) went without a prescribed medication in 2007 as white beneficiaries (6.2%). In addition, Medicare beneficiaries under age 65—typically eligible because of permanent disability or severe kidney disease—had more than three times the prescription drug access problems (27.5%) as elderly beneficiaries in 2007.

![]() he proportion of Medicare beneficiaries 65 and older reporting

problems affording prescription drugs remained unchanged between 2003 and 2007.

In both years, about 8 percent of elderly beneficiaries reported they could

not afford to fill a prescription in the previous 12 months, according to findings

from HSC’s nationally representative 2007 Health Tracking Household Survey (see

Data Source and Table 1). This translates

to approximately 2.5 million of the more than 30 million full-year elderly noninstitutionalized

Medicare beneficiaries living in the community going without at least one prescribed

medication in 2007.

he proportion of Medicare beneficiaries 65 and older reporting

problems affording prescription drugs remained unchanged between 2003 and 2007.

In both years, about 8 percent of elderly beneficiaries reported they could

not afford to fill a prescription in the previous 12 months, according to findings

from HSC’s nationally representative 2007 Health Tracking Household Survey (see

Data Source and Table 1). This translates

to approximately 2.5 million of the more than 30 million full-year elderly noninstitutionalized

Medicare beneficiaries living in the community going without at least one prescribed

medication in 2007.

While the proportion of elderly Medicare beneficiaries who couldn’t afford a prescription drug remained stable between 2003 and 2007, working-age adults didn’t fare as well, with sizeable increases in prescription drug access problems for both the uninsured and those with employer-based coverage.1 The proportion of privately insured, working-age adults—the group most similar to elderly Medicare beneficiaries in terms of insurance coverage—going without a prescription drug because of cost increased from 8.8 percent in 2003 to 10.8 percent in 2007.

A key difference between Medicare seniors and working-age adults with prescription drug coverage is that the Medicare drug benefit has a coverage gap—known as the doughnut hole—when beneficiaries are responsible for the full cost of their drugs out of pocket. In 2007, the coverage gap began when a beneficiary incurred $2,400 in total drug spending and ended after out-of-pocket spending reached $3,850, equivalent to $5,451 in total drug spending.

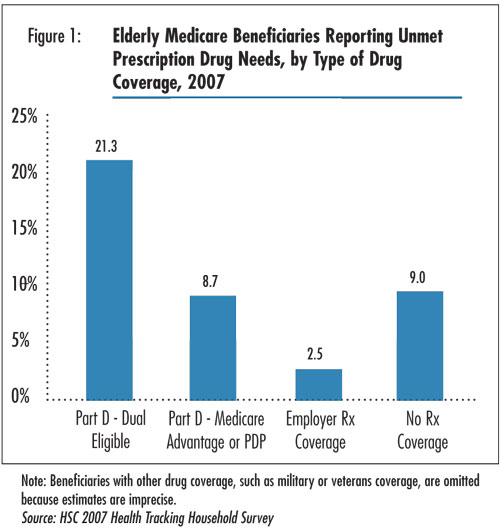

![]() ccess to prescription drugs varies considerably across

elderly Medicare beneficiaries, reflecting differences in the source of their

drug coverage and differences in age, health and income. Under the Medicare

drug benefit, known as Part D, beneficiaries can obtain creditable drug coverage

from an employer or union plan that is at least comparable to the Part D standard

benefit, obtain drug coverage through a private Medicare Advantage plan, enroll

in a stand-alone Medicare prescription drug plan (PDP), or go without coverage.

Most elderly beneficiaries who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid

are automatically enrolled in a stand-alone PDP (see Figure

1).

ccess to prescription drugs varies considerably across

elderly Medicare beneficiaries, reflecting differences in the source of their

drug coverage and differences in age, health and income. Under the Medicare

drug benefit, known as Part D, beneficiaries can obtain creditable drug coverage

from an employer or union plan that is at least comparable to the Part D standard

benefit, obtain drug coverage through a private Medicare Advantage plan, enroll

in a stand-alone Medicare prescription drug plan (PDP), or go without coverage.

Most elderly beneficiaries who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid

are automatically enrolled in a stand-alone PDP (see Figure

1).

Even after adjusting for differences in beneficiaries’ age, health and income, differences in prescription drug access by source of drug coverage narrowed only slightly, with basic patterns remaining. Among seniors with Part D coverage who are not dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, 8.7 percent reported unmet prescription needs in 2007, about the same level (9%) as elderly beneficiaries without drug coverage. One possible explanation is that beneficiaries without drug coverage may have fewer drug needs than those enrolled in Part D, even after adjusting for general health status and chronic conditions.

Moreover, the doughnut hole may impede access. About one-quarter of PDPs and Medicare Advantage plans offered some coverage for prescription drugs in the doughnut hole in 2007 but typically only for generic drugs.2 Also, plans with such coverage tend to have higher premiums, potentially putting them out of reach for lower-income beneficiaries who face greater challenges affording prescription drugs. Although beneficiaries can choose among plans with and without deductibles, deductibles also can result in large increases in out-of-pocket drug costs at the beginning of the year.

Elderly Medicare beneficiaries with employer drug coverage reported the lowest rate of unmet needs in 2007 at 2.5 percent. Beneficiaries with employer drug coverage tend to have higher incomes and fewer health problems than beneficiaries with other types of drug coverage.3 Also, employer-sponsored drug benefits typically do not have doughnut holes and usually offer more generous coverage than Medicare Part D.

At the other extreme, dually eligible beneficiaries had much greater problems affording prescription medications, despite auto-enrollment in stand-alone PDPs and automatically receiving the low-income subsidy (LIS). The LIS eliminates premiums for the standard benefit and deductibles, provides coverage in the doughnut hole, and limits beneficiary cost sharing. Nonetheless, more than two in 10 elderly dually eligible beneficiaries reported not being able to afford prescription drugs.

![]() ecause Part D prescription drug plans did not exist in 2003, trends related to unmet prescription drug needs by type of drug coverage cannot be fully investigated. One exception is beneficiaries dually eligible for Medicaid and Medicare. In 2003, dually eligible beneficiaries received drug coverage through Medicaid, but the advent of the new Medicare drug benefit shifted their drug coverage to Medicare. Between 2003 and 2007, elderly beneficiaries dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid experienced a two-fold increase in unmet prescription drug needs. In 2003, 10.8 percent reported difficulty affording prescription drugs, which grew to 21.3 percent in 2007.

ecause Part D prescription drug plans did not exist in 2003, trends related to unmet prescription drug needs by type of drug coverage cannot be fully investigated. One exception is beneficiaries dually eligible for Medicaid and Medicare. In 2003, dually eligible beneficiaries received drug coverage through Medicaid, but the advent of the new Medicare drug benefit shifted their drug coverage to Medicare. Between 2003 and 2007, elderly beneficiaries dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid experienced a two-fold increase in unmet prescription drug needs. In 2003, 10.8 percent reported difficulty affording prescription drugs, which grew to 21.3 percent in 2007.

The switch in responsibility for administering prescription drug benefits for dual-eligibles from state Medicaid programs to private health plans under Part D may have contributed to the access decline. Transition problems in the first months of 2006, when some dual-eligibles faced difficulties verifying coverage or were overcharged for medications, likely contributed to access problems. However, in examining only elderly dually eligible survey respondents interviewed after July 1, 2007, whose reports of unmet prescription needs do not include the first six months that the Medicare Part D benefit was in effect, rates of unmet prescription drug need declined only slightly from 21.3 percent to 18.1 percent. Another factor that may have contributed to access problems is that dually eligible beneficiaries often face higher costs and more limited formularies under the Medicare drug benefit than they did in state Medicaid programs.4

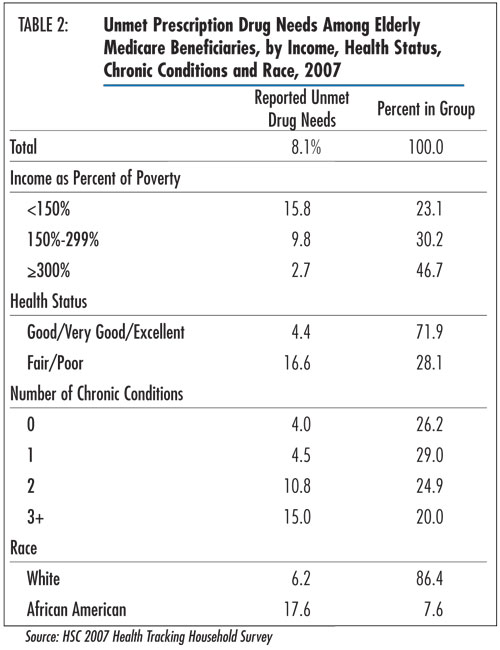

![]() he new Medicare drug benefit did little to close large

prescription drug access gaps between elderly white and African-American beneficiaries

and healthier and sicker beneficiaries (see Table 2).5

In 2007, almost three times as many elderly African-American beneficiaries (17.6%)

went without a prescribed medication as white beneficiaries (6.2%), while nearly

four times as many elderly beneficiaries in fair or poor health (16.6%) skipped

filling a prescription compared with those in good to excellent health (4.4%).

Moreover, four times as many elderly beneficiaries with three or more chronic

conditions (15%) went without a prescription because of cost as those without

chronic conditions (4%).

he new Medicare drug benefit did little to close large

prescription drug access gaps between elderly white and African-American beneficiaries

and healthier and sicker beneficiaries (see Table 2).5

In 2007, almost three times as many elderly African-American beneficiaries (17.6%)

went without a prescribed medication as white beneficiaries (6.2%), while nearly

four times as many elderly beneficiaries in fair or poor health (16.6%) skipped

filling a prescription compared with those in good to excellent health (4.4%).

Moreover, four times as many elderly beneficiaries with three or more chronic

conditions (15%) went without a prescription because of cost as those without

chronic conditions (4%).

Likewise, low-income elderly Medicare beneficiaries have greater unmet prescription drug needs than higher-income beneficiaries. Almost 16 percent of beneficiaries with incomes below 150 percent of the federal poverty level—$15,315 for an individual or $20,535 for a couple in 2007—reported unmet prescription drug needs in 2007, compared with 2.7 percent of beneficiaries with incomes at or above 300 percent of poverty. Many beneficiaries with incomes below 150 percent of the poverty level, even if they are not eligible for Medicaid, are eligible for the LIS.

![]() he proportion of nonelderly Medicare beneficiaries—typically eligible because of permanent disability or severe kidney disease—that went without a prescription drug because of cost was high in 2007 at 27.5 percent but remained unchanged from 2003.

he proportion of nonelderly Medicare beneficiaries—typically eligible because of permanent disability or severe kidney disease—that went without a prescription drug because of cost was high in 2007 at 27.5 percent but remained unchanged from 2003.

About 40 percent of nonelderly Medicare beneficiaries living in the community are dually eligible for Medicaid, compared with about 10 percent of elderly Medicare beneficiaries. Nonelderly dual-eligibles experienced even higher rates of unmet prescription drug needs than their elderly counterparts, with about three in 10 reporting problems affording a prescription drug. Unlike their elderly counterparts, unmet prescription drug needs among nonelderly dual-eligibles did not increase between 2003 and 2007. A possible explanation is that Part D drug plans are required to cover all drugs in certain classes of medications used to treat psychiatric disorders, which particularly affect nonelderly dual-eligibles.

![]() verall, Medicare beneficiaries’ access to prescription drugs remained stable between 2003 and 2007, suggesting the new Medicare drug benefit may have prevented a decline in seniors’ access at a time when more working-age adults reported prescription drug affordability problems.

verall, Medicare beneficiaries’ access to prescription drugs remained stable between 2003 and 2007, suggesting the new Medicare drug benefit may have prevented a decline in seniors’ access at a time when more working-age adults reported prescription drug affordability problems.

Although out-of-pocket prescription drug expenses for elderly Medicare beneficiaries as a whole have declined under Part D,6 most Medicare PDPs, including Medicare Advantage drug plans, have tiered formularies, meaning that beneficiary cost sharing for brand-name and specialty drugs may be substantial. Use of specialty drugs, drug prices and prescribing rates generally all increased between 2003 and 2007. These trends mean that more beneficiaries will enter the doughnut hole, and this gap in coverage will only become more problematic as the size of the doughnut hole expands each year and health plans’ coverage of that gap becomes more limited.7

Of particular concern are the high and, in some cases, rising rates of unmet prescription drug needs among the most vulnerable Medicare beneficiaries. Those with low incomes or high prescription drug needs are more likely to experience problems affording prescription drugs. The Medicare drug benefit was structured to shield beneficiaries dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid and other low-income beneficiaries from cost concerns through relief from premiums, low cost-sharing requirements and exemption from the doughnut hole. But, even modest cost-sharing requirements and restrictions on which drugs are covered can pose substantial financial burdens. Moreover, many low-income beneficiaries eligible for the low-income subsidy remain unenrolled.8 In addition, the sheer number of different drug plan choices, changing prescription drug formularies, and the complexity of the benefit may have created significant challenges for beneficiaries to navigate the system and obtain the drugs they need.

The basic structure of the Part D benefit—the doughnut hole and the ability of private health plans to affect access through deductibles, cost sharing and drug formularies—may contribute to problems affording prescription drugs, particularly for lower-income beneficiaries. These features mean that out-of-pocket costs can vary considerably over the course of a year and depend on the specific drugs beneficiaries’ physicians prescribe for them.

Other research suggests that the doughnut hole has a significant impact on access to prescription drugs. In 2007, one-quarter of Part D enrollees—who filled at least one prescription drug and did not receive the low-income subsidy—fell into the doughnut hole, and most (85%) remained in the doughnut hole for the remainder of the year. And, 15 percent of beneficiaries in the doughnut hole stopped taking their medication in 2007.9 Although additional assistance for low-income beneficiaries may be available from state and pharmaceutical manufacturers’ assistance programs, access to such assistance by low-income Medicare beneficiaries is limited.10

Drug access problems for Medicare beneficiaries will likely grow in the future. Although recent trends in drug spending have slowed and some widely used prescription drugs face expiring patents, prescribing rates by physicians will likely continue to grow and the doughnut hole is set to increase in size. Perhaps of greater concern, the recent economic downturn has eroded assets and cut incomes of many Medicare beneficiaries, making prescription drugs less affordable.

This Tracking Report presents findings from the HSC 2007 Health Tracking Household Survey and the 2003 Community Tracking Study Household Survey. Both telephone surveys used nationally representative samples of the civilian, noninstitutionalized population. Sample sizes included about 47,000 people for the 2003 survey and about 18,000 people for the 2007 survey. Estimates are based on samples of about 7,500 and 3,200 Medicare beneficiaries in 2003 and 2007, respectively. Response rates for the surveys were 57 percent in 2003 and 43 percent in 2007. Population weights adjust for probability of selection and differences in nonresponse based on age, sex, race or ethnicity, and education. Although both surveys are nationally representative, the sample for the 2003 survey was largely clustered in 60 representative communities, while the 2007 survey was based on a stratified random sample of the nation. Standard errors account for the complex sample design of the surveys. Questionnaire design, survey administration and the question wording of all measures in this study were similar across both surveys.

Estimates of unmet need for prescription drugs were based on the following

question: “During the past 12 months, was there any time you needed prescription

medicines but didn’t get them because you couldn’t afford it?”

We include in the analysis respondents who have been Medicare beneficiaries

for at least 12 months. Most 2007 survey respondents (74%) were interviewed

after July 1, which meant that the look-back period did not include the first

six months of the Part D drug benefit, when transition problems might have resulted

in access difficulties.

Funding Acknowledgements: This research was funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The HSC 2007 Health Tracking Household Survey and the HSC 2003 Community Tracking Study Household Survey used for the analysis were funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

TRACKING REPORTS are published by the

Center for Studying Health System Change.

600 Maryland Avenue, SW, Suite 550

Washington, DC 20024-2512

Tel: (202) 484-5261

Fax: (202) 484-9258

www.hschange.org