HSC Research Brief No. 11

April 2009

Ann Tynan, Elizabeth A. November, Johanna Lauer, Hoangmai H. Pham, Peter Cram

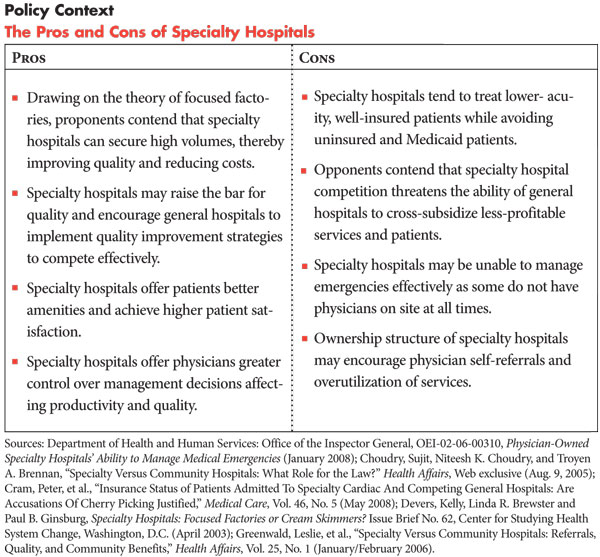

In the past decade, the rapid growth of specialty hospitals focused on profitable service lines, including cardiac and orthopedic care, has prompted concerns about general hospitals’ ability to compete. Critics contend specialty hospitals actively draw less-complicated, more-profitable patients with Medicare and private insurance away from general hospitals, threatening general hospitals’ ability to cross-subsidize less-profitable services and provide uncompensated care. A contentious debate has ensued, but little research has addressed whether specialty hospitals adversely affect the financial viability of general hospitals and their ability to care for low-income, uninsured and Medicaid patients. Despite initial challenges recruiting staff and maintaining service volumes and patient referrals, general hospitals were generally able to respond to the initial entry of specialty hospitals with few, if any, changes in the provision of care for financially vulnerable patients, according to a new study by the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC) of three markets with established specialty hospitals—Indianapolis, Phoenix and Little Rock, Ark. In addition, safety net hospitals—general hospitals that care for a disproportionate share of financially vulnerable patients—reported limited impact from specialty hospitals since safety net hospitals generally do not compete for insured patients.

![]() mid concerns that specialty hospitals “cream-skim” more-profitable,

less-complicated, well-insured patients from general hospitals, Congress in

2003 mandated an 18-month Medicare moratorium on physician self-referrals to

new physician-owned specialty hospitals, effectively stalling their development

(See box for more about specialty hospital pros and cons).

Specialty hospitals and general hospitals typically compete for profitable service

lines, such as cardiac and orthopedic care, which because of unintended payment

rate distortions tend to be more lucrative.1

mid concerns that specialty hospitals “cream-skim” more-profitable,

less-complicated, well-insured patients from general hospitals, Congress in

2003 mandated an 18-month Medicare moratorium on physician self-referrals to

new physician-owned specialty hospitals, effectively stalling their development

(See box for more about specialty hospital pros and cons).

Specialty hospitals and general hospitals typically compete for profitable service

lines, such as cardiac and orthopedic care, which because of unintended payment

rate distortions tend to be more lucrative.1

General hospitals often rely on profitable services and patients to subsidize unprofitable services and patients. Faced with the loss of profitable services and patients to specialty hospitals, some feared that general hospitals might curtail emergency services, close burn or psychiatric units or provide less uncompensated care. Whether specialty hospitals compromise general hospitals’ financial viability and ability to cross-subsidize care for financially vulnerable populations—low-income, uninsured and Medicaid patients—remains a debated issue.2

Since the 2003 moratorium, a body of research has been conducted evaluating physician-owned specialty hospitals. Generally, the research indicates that specialty hospitals treat less-complex patients with lower acuity3 and a higher proportion of patients with more generous insurance coverage.4 In addition, physician ownership interests in specialty hospitals may result in referral patterns that shift patient volume from general to specialty hospitals.5

In 2007, in an effort to improve payment accuracy based on patient acuity and reduce cream skimming by all types of hospitals—which rely on Medicare for a significant portion of their revenue—the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services began phasing in severity-based adjustments and other changes to Medicare payments for inpatient care.

![]() his study examines the impact of specialty hospitals—cardiac,

surgical and orthopedic—on the ability of general and safety net hospitals

to care for financially vulnerable patients in Indianapolis, Little Rock and

Phoenix (see Data Source). While these markets are not nationally

representative, and specialty hospitals represent a relatively limited share

of the overall inpatient market, their experiences are useful in illustrating

the range of hospital responses to the market entry of specialty hospitals.

Each of the three communities has an established presence of specialty hospitals,

general hospitals that provide care to financially vulnerable populations and

a major safety net hospital that primarily serves low-income and uninsured patients.

his study examines the impact of specialty hospitals—cardiac,

surgical and orthopedic—on the ability of general and safety net hospitals

to care for financially vulnerable patients in Indianapolis, Little Rock and

Phoenix (see Data Source). While these markets are not nationally

representative, and specialty hospitals represent a relatively limited share

of the overall inpatient market, their experiences are useful in illustrating

the range of hospital responses to the market entry of specialty hospitals.

Each of the three communities has an established presence of specialty hospitals,

general hospitals that provide care to financially vulnerable populations and

a major safety net hospital that primarily serves low-income and uninsured patients.

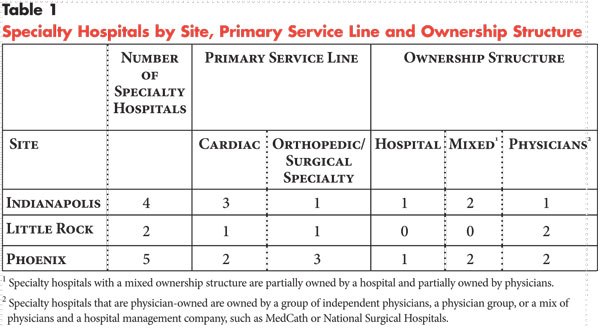

The three communities vary in terms of ownership structures of specialty hospitals (see Table 1) and the level of specialty physician consolidation. However, all three markets lack certificate-of-need requirements that can restrict the growth of specialty hospitals.

In Indianapolis, where there are a few very large single-specialty medical groups,6 cardiac specialty hospitals began as joint ventures between local general hospital systems and physicians. Over time, they became majority-owned by the hospital systems. In Little Rock, which has large single-specialty medical groups,7 the only stand-alone cardiac specialty hospital is owned by physicians affiliated in a medical group and MedCath, a corporation that operates specialty hospitals. In Phoenix, with fewer single-specialty medical groups than Little Rock,8 one of the cardiac specialty hospitals also is owned by physicians and MedCath, while the surgical specialty hospital is wholly owned by physicians. Orthopedic specialty hospitals in the three communities are typically wholly owned by physicians.

Specialty hospitals in the three markets were established between 2000 and 2005, with the exception of a heart hospital in Little Rock in 1997 and a heart hospital in Phoenix in 1998. Across all three markets, general hospital systems lacking ownership interest in stand-alone specialty hospitals operate competing specialty-service lines, for example, through a center of excellence for cardiac care or orthopedics.

![]() tudy respondents identified several ways that specialty hospital competition affected the financial well-being of general and safety net hospitals through competition for physicians and other staff, new challenges in providing emergency department (ED) on-call coverage and decreases in service volume. Respondents reported little, if any, change in patient acuity in general hospitals. And respondents more often attributed changes in payer mix to the rising rate of uninsured people in the market generally, rather than the loss of patient volume to specialty hospitals. General hospitals were more likely than safety net hospitals to feel the impact of competition from specialty hospitals.

tudy respondents identified several ways that specialty hospital competition affected the financial well-being of general and safety net hospitals through competition for physicians and other staff, new challenges in providing emergency department (ED) on-call coverage and decreases in service volume. Respondents reported little, if any, change in patient acuity in general hospitals. And respondents more often attributed changes in payer mix to the rising rate of uninsured people in the market generally, rather than the loss of patient volume to specialty hospitals. General hospitals were more likely than safety net hospitals to feel the impact of competition from specialty hospitals.

Specialty hospitals initially attracted physicians and other staff from general hospitals and, to a lesser extent, safety net hospitals. An ownership stake in a specialty hospital enables physicians to have a larger role in hospital governance and share in the hospital’s profits. A few general hospitals reported losing significant numbers of cardiologists, orthopedists or other specialists who left to start their own hospitals or enter joint ventures with a corporate entity.

For physicians, specialty hospitals can offer greater control over their work environment, such as more predictable scheduling and more access to operating rooms and diagnostic equipment. Respondents also noted that physicians may be drawn to specialty hospitals because of efficiencies associated with focusing on a single service line and the opportunity to see more patients at one location, reducing the inefficiency of traveling among hospitals.

Specialty hospitals also increased competition for other clinical staff, such as nurses and diagnostic technicians, by offering competitive compensation packages and more predictable work hours. As one specialty hospital respondent noted, “We have been very successful at recruiting full-time nurses. And nurses are in a shortage, so I imagine there is some withdrawal [from other hospitals].” Specialty hospitals also enable non-physician staff to focus on a particular specialty, potentially creating a less stressful and more predictable work environment compared with general hospitals where the demands of the patients and physicians change daily.

Safety net hospitals in two markets that also are academic medical centers reported being somewhat buffered from losing physicians, because physicians at these hospitals are often employees and would have to start or join a private practice to move to a specialty hospital. Also academic medical centers have complex case loads and teaching opportunities that attract physicians. Respondents also noted that their physicians, nurses and other staff may be attracted to the organizations’ mission to serve the underserved in the community.

General and safety net hospitals also faced challenges getting specialists who retain admitting privileges at their facilities to take on-call coverage and this situation has worsened because of the entry of specialty hospitals, according to respondents. Physicians practicing at specialty hospitals with very small or no emergency departments have little or no obligation for ED call coverage. Specialists, particularly newly trained physicians with different lifestyle expectations—such as work-life balance, shorter work weeks—than previous generations, may prefer not to have on-call obligations and may choose to practice at a specialty hospital rather than a general hospital. Or they may threaten to move to a specialty hospital in negotiating for reduced call responsibilities at general hospitals.

According to one hospital association respondent, “Every hospital has a requirement in their bylaws that physicians will take ED call as part of having medical staff privileges. More and more physicians are saying ‘I don’t care what’s in the bylaws, I’m not doing it. You can throw me off the medical staff.’ Specialty hospitals have contributed to and exacerbated the problem [lack of ED call coverage] without a doubt, but the problem is beyond them.”

General hospitals have responded to the increased competition for staff and call coverage in various ways. Some hospitals, particularly those that have lost specialist physicians to specialty hospitals, have employed specialists or aggressively aligned with specialists who practice at multiple facilities via contractual arrangements, encouraging them to concentrate their practice at a particular hospital. This strategy also helped general hospitals rebound from initial losses in service volume to specialty hospitals. General hospitals also reported adapting the hospital environment to better accommodate physicians’ preferences, such as making more operating rooms available to them.

One Little Rock general hospital took a more aggressive approach, using economic credentialing for its medical staff, which bars physicians with admitting privileges or their family members from having financial interests in competing specialty hospitals. In recent years, there have been highly publicized court cases related to the general hospital’s economic credentialing policy, as well as a lawsuit alleging that the general hospital aligned with the state’s largest insurer to avoid competition by keeping physicians affiliated with specialty hospitals out of the insurer’s network. Finally, general and safety net hospitals often have to pay significant money to ensure emergency call coverage and, in some cases, recruit specialists from outside of the market, which has resulted in increased costs.

General hospitals in all three communities and a safety net hospital in Little Rock observed a drop in service volume upon the entry of specialty hospitals. Some respondents suggested that the drop in service volume may have been caused at least in part by the loss of patients as physicians left the general hospital staff to join the specialty hospital staff. Additionally, specialists with privileges at both general and specialty hospitals may have begun preferentially referring patients to the specialty hospital. However, hospital executives acknowledged that other factors beyond specialty hospitals might have affected their service volumes.

According to hospital executives, some market factors may have shielded general hospitals from worse losses in service volume. Phoenix—which has experienced rapid population growth in recent years—had relatively low per-capita hospital capacity, which may have ensured sufficient patient demand to offset any noticeable drop in service volume at general hospitals when specialty hospitals entered the market. Respondents also noted that changes in medical technology may have prompted a decline in cardiac service volume at general hospitals—there has been a nationwide drop in cardiac surgeries because of increased use of stents and balloon angioplasty as alternatives to cardiac bypass surgery. According to a Little Rock hospital respondent, “There have been trends in technology offerings related to fewer bypass procedures and more procedures in the catheterization lab. So there’s a definite decrease in surgical procedures that’s not necessarily related to the heart hospital.”

Safety net hospitals reported little impact on service volume because of the presence of specialty hospitals, since safety net hospitals generally do not compete intensely for patients with private insurance or Medicare. According to one safety net hospital respondent, “Our competitors don’t want us to fail. they don’t want us to compete, but don’t want us to go away because then they’d have to deal with our patients.”

General hospitals and a safety net hospital reported using various strategies to respond to the initial losses in service volume. As discussed earlier, general hospitals increased employment of specialists or more tightly aligned themselves with specialists as strategies to retain staff and to preserve, if not grow, service volume. General hospitals in Indianapolis and Little Rock, for example, reported developing new specialty-service lines, mainly for orthopedic services. Respondents noted that some general hospitals began advertising campaigns to promote cardiac services and facilities as a way to increase demand. A state insurance regulator explained, “General hospitals are doing a whole lot of advertising now. And the area of heart and cancer are two of the areas where they’re doing a lot of heavy advertising and seeing they need to do that to compete.”

General and safety net hospital respondents generally did not observe specialty hospitals as cream skimming less-complicated, lower-risk patients. General hospital respondents in Little Rock and Phoenix reported higher patient acuity since the entry of specialty hospitals but couldn’t specifically attribute this to specialty hospitals. Moreover, respondents reported that transfers from specialty hospitals to general or safety net hospitals generally are rare in contrast to recent media reports that specialty hospitals off-load complicated patients to general and safety net hospitals.9

A few general and safety net hospitals noted serving more financially vulnerable patients. In some cases, hospitals attributed these changes in payer mix to a loss of insured patients to specialty hospitals. More often, however, respondents, particularly safety net hospitals, attributed changes in payer mix to an overall increase in the number of uninsured in their respective markets. Further, the leading general hospitals likely were able to cost shift to private payers by negotiating increases in payment rates to cross-subsidize losses from charity care and Medicaid.

Respondents observed little impact on payer mix from the introduction of Medicare severity-adjusted diagnostic related groups that allow higher reimbursements for sicker patients. These reimbursement changes haven’t yet had the leveling effect between general hospitals and specialty hospitals (boosting reimbursement to general hospitals and reducing reimbursement to specialty hospitals) anticipated by policy makers, assuming the presence of cream skimming by specialty hospitals. According to respondents, the changes helped all hospitals caring for a greater proportion of higher-severity patients. General and specialty hospitals that have a mix of patients with different levels of acuity reported seeing no change in payments.

![]() hile specialty hospitals affected general hospitals’ ability

to attract and retain physicians and other staff and service volumes, general

hospitals’ responses limited the impact on their financial viability. In a 2006

study, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) similarly reported

that, “While specialty hospitals took profitable surgical patients from the

competitor community hospitals (slowing Medicare revenue growth at some hospitals),

most competitor community hospitals appeared to compensate for this lost revenue.”10

hile specialty hospitals affected general hospitals’ ability

to attract and retain physicians and other staff and service volumes, general

hospitals’ responses limited the impact on their financial viability. In a 2006

study, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) similarly reported

that, “While specialty hospitals took profitable surgical patients from the

competitor community hospitals (slowing Medicare revenue growth at some hospitals),

most competitor community hospitals appeared to compensate for this lost revenue.”10

General and safety net hospital respondents did not report changes in the provision of care for financially vulnerable patients as a result of specialty hospital competition. One general hospital each in Indianapolis and Little Rock reported that competition from specialty hospitals has strained their ability to cross-subsidize services but did not report limiting care to financially vulnerable patients. Many respondents noted that competition by specialty hospitals is only one of many factors that affect the financial stability of general and safety net hospitals, including cost increases outpacing payment rate increases from Medicare and Medicaid.

According to one Indianapolis general hospital executive, “Specialty hospitals definitely have an impact. At the same time you have to say the reimbursement levels and government programs aren’t going up as fast as the cost is going up. Costs are going up double digits, but we get a single-digit increase on Medicare and things like that. You have that as another hurdle that is having an impact on your economic health.” This assessment was echoed by a Phoenix general hospital executive, “If you asked me the three-to-five factors on financial performance [in general hospitals], specialty hospitals wouldn’t be in that list.”

![]() o date, the entry of specialty hospitals to the Indianapolis, Little Rock and Phoenix markets has not had dramatic, adverse effects on the financial viability of general and safety net hospitals and their ability to provide care to financially vulnerable populations. However, this seems largely because of the ability of general hospitals to compensate for the competition in various ways. General hospitals likely have enjoyed sufficient market leverage in recent years to allow them to cost-shift to private payers without reducing unprofitable services that provide community benefit, such as burn units and psychiatric care.

o date, the entry of specialty hospitals to the Indianapolis, Little Rock and Phoenix markets has not had dramatic, adverse effects on the financial viability of general and safety net hospitals and their ability to provide care to financially vulnerable populations. However, this seems largely because of the ability of general hospitals to compensate for the competition in various ways. General hospitals likely have enjoyed sufficient market leverage in recent years to allow them to cost-shift to private payers without reducing unprofitable services that provide community benefit, such as burn units and psychiatric care.

In the context of the current economic recession, however, it is unclear whether general hospitals will be able to continue cost-shifting to private payers that must balance the demands for provider payment rate increases with employer-purchaser pressures to contain escalating health care costs and insurance premiums. General hospitals will likely experience an increased burden of uncompensated care as job losses in the worsening economy are accompanied by the loss of health insurance. According to one estimate, for every 1 percent increase in unemployment, the number of uninsured grows by 1.1 million.11 Further, general hospitals’ reserves and investment portfolios, which can help offset increases in the cost of uncompensated care, have likely lost significant value. As financial constraints tighten, general hospitals may seek alternative remedies to specialty hospital competition, such as economic credentialing. Consequently, pending court decisions could have significant policy implications for the ability of general hospitals to manage competition from specialty hospitals.

Broader market changes and the worsening economic recession—characterized by job loss, increased number of uninsured, more difficult debt financing, reduced or stagnant reimbursement by private payers—likely will adversely affect specialty hospitals as well. Specialty hospitals burgeoned in times of relative economic prosperity. How specialty hospitals in the three communities will cope with a shrinking base of privately insured patients and reductions in elective procedures already reported by hospitals around the country remains to be seen.

Severity adjustments to Medicare inpatient hospital payment rates haven’t had a noticeable impact on the hospitals in the three communities; however, these payment changes haven’t been fully phased in. Over time, it is possible that severity-adjusted payments may prove to do more to support general hospitals. The continued effort by Medicare to accurately price inpatient services based on patient acuity will be integral to future policy regarding specialty hospitals. Moreover, it will be important for policy makers to continue to track the impact of specialty hospitals on the ability of general hospitals—more so than safety net hospitals—to serve financially vulnerable patients and provide other less-profitable but needed services.

| 1. | Ginsburg, Paul B., and Joy M. Grossman, “When the Price Isn’t Right: How Inadvertent Payment Incentives Drive Medical Care,” Health Affairs, Web exclusive (Aug. 5, 2005). |

| 2. | Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC), Report to the Congress: Physician-Owned Specialty Hospitals, Washington, D.C. (March 2005); Moore, Keith, and Dean Coddington, “Specialty Hospital Rise Could Add to Full-Service Hospital Woes,” Healthcare Financial Management (July 2005). |

| 3. | Greenwald, Leslie, et al., “Specialty Versus Community Hospitals: Referrals, Quality, and Community Benefits,” Health Affairs, Vol. 25, No. 1 (January/February 2006). |

| 4. | Cram, Peter, et al., “Insurance Status of Patients Admitted to Specialty Cardiac and Competing General Hospitals: Are Accusations of Cherry Picking Justified,” Medical Care, Vol. 46, No. 5 (May 2008). |

| 5. | Greenwald, et al. (2006). |

| 6. | Devers, Kelly, Linda R. Brewster and Paul B. Ginsburg, Specialty Hospitals: Focused Factories or Cream Skimmers? Issue Brief No. 62, Center for Studying Health System Change, Washington, D.C. (April 2003). |

| 7. | Katz, Aaron, et al., Little Rock Providers Vie for Revenues, As High Health Care Costs Continue, Community Report No. 3, Center for Studying Health System Change, Washington, D.C. (July 2005). |

| 8. | Trude, Sally, et al., Rapid Population Growth Outpaces Phoenix Health System Capacity, Community Report No. 6, Center for Studying Health System Change, Washington, D.C. (September 2005). |

| 9. | “5 Investigates Hospitals Calling 911,” KPHO (Julys 27, 2007) at http://www.kpho.com/iteam/13770265/detail.html. |

| 10. | MedPAC, Report to Congress: Physician-Owned Specialty Hospitals, Revised, Washington, D.C. (August 2006). |

| 11. | Holahan, John, and Bowen Garrett, Rising Unemployment, Medicaid and the Uninsured, prepared for the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured (January 2009). |

To examine the impact of specialty hospitals on the ability of general and

safety net hospitals to care for vulnerable populations, HSC conducted key stakeholder

interviews in three Community Tracking Study communities with an established

presence of specialty hospitals. These communities are Indianapolis, Little

Rock and Phoenix. In each of these communities, researchers interviewed representatives

from physician practices, community health centers, emergency medical services,

medical societies, hospital associations, state regulatory agencies, and other

respondents who could provide a market-wide perspective. Interviews also were

conducted with hospital executives of at least two general hospitals, two specialty

hospitals and one safety net hospital in each community, with the exception

of Little Rock. Researchers were unable to interview executives from the two

specialty hospitals in Little Rock (because of ongoing litigation (heart hospital)

and changes in leadership (surgical hospital)). The findings are based on semi-structured

phone interviews with 43 respondents conducted by two-person interview teams

between March and June 2008, and interveiw data were analyzed using Atlas.ti,

a qualitative software package.

This research was funded by a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Physician Faculty Scholars Program grant to Dr. Peter Cram of the University of Iowa.

ISSUE BRIEFS are published by the Center for Studying Health System

Change.

600 Maryland Avenue, SW, Suite 550

Washington, DC 20024-2512

Tel: (202) 484-5261

Fax: (202) 484-9258

www.hschange.org