Community Report No. 4

December 2010

Laurie E. Felland, Grace Anglin, Amelia M. Bond, Gary Claxton, Ann S. O'Malley, Caroleen W. Quach

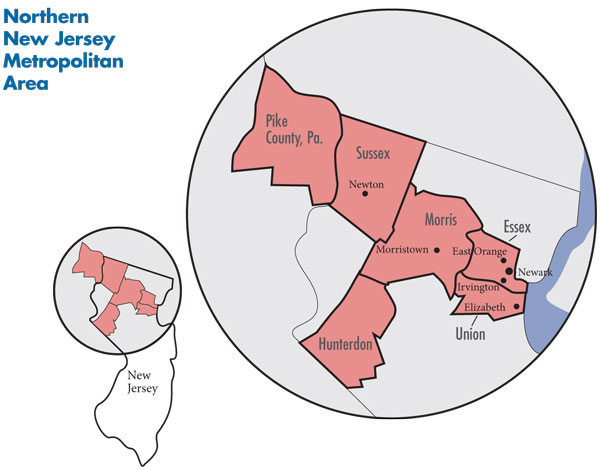

In May 2010, a team of researchers from the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC), as part of the Community Tracking Study (CTS), visited the northern New Jersey metropolitan area to study how health care is organized, financed and delivered in that community. Researchers interviewed more than 40 health care leaders, including representatives of major hospital systems, physician groups, insurers, employers, benefits consultants, community health centers, state and local health agencies, and others. The northern New Jersey metropolitan area encompasses Essex, Hunterdon, Morris, Sussex and Union counties in New Jersey and Pike County, Pa.

![]() orthern New Jersey is a community of contrasts with affluent suburbs and financially strong health care providers juxtaposed against the fragile health care safety net of impoverished inner-city Newark. Excess provider capacity, comprehensive insurance coverage and residents’ high incomes have contributed to high health care costs in the suburbs, although several recent hospital closures and nascent moves toward more restrictive insurance products may help temper rising costs. However, the remaining hospitals, particularly in affluent areas, have more leverage to negotiate higher payment rates from health plans and are expanding profitable services.

orthern New Jersey is a community of contrasts with affluent suburbs and financially strong health care providers juxtaposed against the fragile health care safety net of impoverished inner-city Newark. Excess provider capacity, comprehensive insurance coverage and residents’ high incomes have contributed to high health care costs in the suburbs, although several recent hospital closures and nascent moves toward more restrictive insurance products may help temper rising costs. However, the remaining hospitals, particularly in affluent areas, have more leverage to negotiate higher payment rates from health plans and are expanding profitable services.

At the same time, the economic downturn has led to more uninsured patients for suburban and inner-city hospitals, alike. Significant state budget shortfalls have forced health care program cuts, including a scaling back of public coverage for low-income adults, although the state has maintained its commitment to covering children.

Key developments include:

- A Study of Contrasts

- More Consolidation Expected

- Hospitals Compete for Well-Insured Patients

- Physician Strategies to Boost Income

- Pressure on Insurers to Control Costs

- Growing Interest in Wellness Programs

- Safety Net Focuses on Primary Care

- State Focuses on Covering Children; Adults Lose Ground

- Anticipating Health Care Reform

- Issues to Track

- Background Data

A Study in Contrasts

![]() ith a population of about 2.1 million people, the northern New Jersey metropolitan area (see map below) is marked by significant urban poverty contrasted with suburban wealth. The market encompasses both economically distressed Newark and the urban-ring communities of East Orange and Irvington in Essex County, as well as the working-class city of Elizabeth, just south of Newark in Union County. In contrast, the counties to the west—particularly Morris County—are home to higher-income, white-collar residents with more economic ties to New York City than to Newark or Elizabeth.

ith a population of about 2.1 million people, the northern New Jersey metropolitan area (see map below) is marked by significant urban poverty contrasted with suburban wealth. The market encompasses both economically distressed Newark and the urban-ring communities of East Orange and Irvington in Essex County, as well as the working-class city of Elizabeth, just south of Newark in Union County. In contrast, the counties to the west—particularly Morris County—are home to higher-income, white-collar residents with more economic ties to New York City than to Newark or Elizabeth.

Although northern New Jersey residents overall are more educated and have higher incomes than residents in large metropolitan areas on average, a relatively high percentage of residents speak limited or no English, and there is considerable variation in socioeconomic status among the more-urban and suburban New Jersey counties. For example, approximately 17 percent of Essex and Union county residents were uninsured in 2008, compared to 7-percent uninsured in Morris County. The unemployment rate in May 2010 in Essex County was 11.1 percent—higher than the national rate of 9.3 percent—while more prosperous Morris County had a 7-percent unemployment rate.

The northern New Jersey health care market is served by a number of hospital systems and independent hospitals. The major systems include Saint Barnabas Health Care System, with three acute care hospitals in the metropolitan area studied, and Atlantic Health System, with two acute care hospitals. The two systems together represent approximately 40 percent of inpatient admissions in the market. Trinitas Regional Medical Center, a Catholic teaching hospital, is another key provider. The University Hospital in Newark, the major teaching hospital of the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, is the main safety net hospital and the only state-designated Level I trauma center in the market. Saint Michael’s Medical Center—part of Catholic Health East, a large system with 34 hospitals in 11 states—and Saint Barnabas’ Newark Beth Israel Medical Center also serve a large proportion of low-income people.

The market has a greater supply of specialists and primary care physicians (PCPs) than the average metropolitan area. Still, market observers reported a shortage of PCPs and expressed concern that new physicians were not seeking primary care careers at a rate sufficient to offset expected PCP retirements. Physicians in northern New Jersey generally practice in solo or small group practices, with a small portion working in larger groups.

Nonprofit Horizon Blue Cross Blue Shield of New Jersey (Horizon BCBS) has the largest share of the health insurance market, but three for-profit national insurers—Aetna, UnitedHealth Group and CIGNA—have significant shares as well, appealing to the many national employers in the market. Outside of the health care sector, key private employers in New Jersey include retail, food manufacturers and pharmaceutical manufacturers.

More Consolidation Expected

![]() he financial status of northern New Jersey hospitals typically mirrors the socioeconomic differences of the market’s communities and residents. Solely a suburban system with few nearby competitors, Atlantic—Morristown Memorial Hospital in Morris County and Overlook Hospital in Union County—attracts well-insured patients and has greater access to capital and other resources than the more-urban hospitals.

he financial status of northern New Jersey hospitals typically mirrors the socioeconomic differences of the market’s communities and residents. Solely a suburban system with few nearby competitors, Atlantic—Morristown Memorial Hospital in Morris County and Overlook Hospital in Union County—attracts well-insured patients and has greater access to capital and other resources than the more-urban hospitals.

A bigger system than Atlantic, Saint Barnabas has both a suburban and urban presence, with its main campus—Saint Barnabas Medical Center—and Clara Maass Medical Center in the suburbs and Newark Beth Israel in downtown Newark. Saint Barnabas also has three additional acute care hospitals outside the immediate metropolitan area. Reflecting the mix of well-insured to uninsured patients at the system’s different hospitals, Saint Barnabas’ financial status has fluctuated more than Atlantic’s. Trinitas Regional Medical Center, which operates two campuses in Elizabeth, serves a more-moderate income population than the suburban or urban hospitals. On the other end of the spectrum are University Hospital and Saint Michael’s Medical Center, which both face persistent, significant financial struggles because they treat many low-income and uninsured patients living in Newark.

The number of hospitals in the market—and the state more broadly—has declined in recent years. A 2008 report from the Governor’s Commission on Rationalizing Health Care Resources drew attention to an oversupply of hospital beds statewide and suggested that the patient loads of some struggling hospitals could be absorbed by other hospitals. Seven hospitals in the northern New Jersey market have closed for financial reasons in the last 10 years, including two in urban areas surrounding Newark (Irvington and Orange), three outside of Elizabeth in Union County—Union Hospital, HealthSouth Specialty Hospital and Muhlenberg Regional Medical Center—and most recently two in inner-city Newark. The Newark hospitals—Columbus Hospital and Saint James Hospital—were closed by the financially ailing Cathedral Healthcare System in 2008, while Catholic Health East acquired Cathedral’s remaining hospital, Saint Michael’s. The number of hospital beds in the market has declined over time, and by 2008 was only slightly higher than the per capita rate for the average large metropolitan area. Still, many market observers believe the market remains over-bedded, primarily in suburban areas.

The reduction in hospital capacity has shifted insured patients to the remaining hospitals, particularly for inpatient and emergency department (ED) care. As one hospital CEO said, “The closures of Muhlenberg, Union, Saint James and Columbus. stabilized the health of the institutions around them.” Increased patient volume contributed to Saint Barnabas’ significant financial improvement between 2008 and 2009, and Saint Michael’s financial performance has improved as the hospital attracted patients previously cared for at the two closed Cathedral hospitals. Further, while the Atlantic and Saint Barnabas systems, given their size and geographic reach, have long had more negotiating leverage with health plans than the area’s other hospitals, reduced hospital capacity elsewhere has strengthened the two systems’ ability to win better payment rates.

However, hospitals’ recent financial gains have been muted by the economic downturn. Although suburban hospital systems reported positive margins, their financial status has fluctuated over the last three years, which they attributed to rising charity care and some declines in inpatient service volume, especially for elective procedures. While Saint Barnabas was able to negotiate more favorable rates with health plans, the system also laid off hundreds of employees to avoid losing money.

The inner-city safety net hospitals have been particularly affected by the economic downturn. Although these hospitals receive assistance from the state’s charity care funding program (see box below), they reported higher and growing charity care costs beyond what the state subsidizes. As the largest provider of charity care, not only in the market but in the state, University Hospital receives by far the largest amount of state charity care dollars but still faces significant challenges because about three-quarters of its patients are publicly insured or uninsured. The hospital had a significant operating loss in 2008 but broke even in 2009 with additional state assistance. While facing similar payer-mix challenges, Saint Michael’s has benefited from joining Catholic Health East, through, for example, savings from materials management and other contracts. Saint Michael’s is redeveloping its main campus, including redesigned inpatient and outpatient facilities and a larger ED. Similarly, Newark Beth Israel benefits from being part of the Saint Barnabas system.

New Jersey’s Charity Care Programs The cost of caring for low-income uninsured patients is partially offset by the state’s two charity care programs, which provide funding to hospitals and federally qualified health centers (FQHCs). Implemented following the repeal of the state’s hospital rate-setting program in 1992, the hospital charity care subsidy program consists of a combination of state funds and taxes on health care providers, matched with federal disproportionate share hospital (DSH) funds. Available funding reached a height of $715 million in 2008, but state budget shortfalls in 2009 and 2010 led the state to reduce funding by about 15 percent, to $605 million. Despite ongoing budget shortfalls, the 2011 budget raises the tax on hospitals and ambulatory care facilities by almost $40 million to generate a total of $665 for the charity care pool. The pool covers a greater percentage of the main safety net hospitals’ charity care costs than those of other hospitals; how the funds are distributed among hospitals has been a perennial issue. The state has provided FQHCs some funding to help cover their charity care costs since the early 1990s and in 2005 established a formal FQHC charity care program. Funded through the tax on hospital revenues, the program disperses $40 million to FQHCs across the state annually. FQHCs are concerned about the static amount of funding—that the amount per visit they receive (currently approximately $100) will decline as FQHC capacity and uninsured patients served continue to grow. Some private physician groups have reported providing growing amounts of charity care, but they do not receive direct support from either of the state charity care programs. However, hospitals and FQHCs may pass some of their funding on to physicians. For example, given the difficulty of finding specialists to treat their patients, some FQHCs spend a small portion of their charity-care dollars to reimburse specialists for consultations, although the FQHCs do not have funds to cover physician fees if patients need follow-up procedures. |

Hositals Compete for Well-Insured Patients

![]() ven as hospitals have gained patients because of reduced capacity elsewhere, they—particularly Atlantic and Saint Barnabas—still compete to attract well-insured patients. Hospitals have long focused on developing more-profitable service lines and reducing less-profitable services. In January 2009, for example, Atlantic opened a large cardiovascular institute on its Morristown Memorial campus and expanded oncology and neuroscience service lines. Saint Barnabas has focused on restructuring its cardiology, oncology, orthopedic and neuroscience services to better attract and keep patients in the system. At the same time, Saint Barnabas closed primary care clinics in low-income areas and nursing homes. Trinitas expanded to become more of a regional medical center with two campuses and a comprehensive cancer center. Market observers asserted that some of the hospitals’ expansions duplicate existing services with the potential to drive up overall costs.

ven as hospitals have gained patients because of reduced capacity elsewhere, they—particularly Atlantic and Saint Barnabas—still compete to attract well-insured patients. Hospitals have long focused on developing more-profitable service lines and reducing less-profitable services. In January 2009, for example, Atlantic opened a large cardiovascular institute on its Morristown Memorial campus and expanded oncology and neuroscience service lines. Saint Barnabas has focused on restructuring its cardiology, oncology, orthopedic and neuroscience services to better attract and keep patients in the system. At the same time, Saint Barnabas closed primary care clinics in low-income areas and nursing homes. Trinitas expanded to become more of a regional medical center with two campuses and a comprehensive cancer center. Market observers asserted that some of the hospitals’ expansions duplicate existing services with the potential to drive up overall costs.

Both Atlantic and Saint Barnabas are expanding their geographic reach, in part because the northern New Jersey population is not growing. Atlantic is looking to the northwest, starting with a planned merger with Newton Memorial Hospital in Sussex County, while Saint Barnabas is trying to attract patients from the east in Hudson County—outside the study area.

Additionally, Atlantic and Saint Barnabas are striving to align with primary care physicians to shore up patient referrals. With more resources to draw on, Atlantic’s alignment strategies are more advanced than Saint Barnabas’. Atlantic’s goal is to affiliate with at least 30 primary care physicians over the next five years, in part to replace retiring PCPs. Atlantic is subsidizing physicians’ costs to adopt electronic medical records (EMRs) as an incentive to affiliate with the system and providing income subsidies and other assistance to small practices, allowing them to hire additional PCPs in areas where a study has documented existing and expected primary care physician shortages.

As another example of greater alignment between hospitals and physicians, Atlantic’s Overlook Hospital and Summit Medical Group, a multispecialty physician practice, are participating in a Medicare gainsharing demonstration project that encourages physicians and hospitals to work together to lower costs and improve quality by allowing them to share any savings.

Despite increased efforts to align with physicians, hospitals in northern New Jersey employ relatively few physicians and show little interest in doing so, bucking a strong national trend. One key exception is employed and contracted hospitalists, who reportedly manage inpatient care for more than half of the patients in the market. Hospital executives cited financial constraints and concerns that physician productivity would decline as reasons they were not pursuing greater employment of physicians. Standing out from other hospitals, Trinitas recently purchased three primary care practices—a total of five physicians—that were under financial strain.

In another strategy to attract insured patients, some hospitals outside of Newark are promoting their emergency departments, a key source of inpatient admissions. Hospital systems are maintaining satellite EDs at sites where inpatient services have closed (although, at least in one case, this was part of a state requirement for allowing the hospital to close). For example, Atlantic took over the ED at Union Hospital after Saint Barnabas closed it. Also, Atlantic started an ambulance and helicopter transport service, and Saint Barnabas is working with the local emergency medical services to simplify drop-off procedures to attract paramedics back with additional patients.

Physician Strategies to Boost Income

![]() ith a few exceptions, physicians in northern New Jersey have historically practiced in solo or small groups. This autonomous nature reflects long-standing physician culture, differences in practice styles and the financial stability that serving a well-insured, suburban patient base provides. Physicians have adopted strategies to generate more revenue—some of which are longstanding and match their independent practice styles, while more recent strategies signal an increasing willingness to partner with other physicians and hospitals.

ith a few exceptions, physicians in northern New Jersey have historically practiced in solo or small groups. This autonomous nature reflects long-standing physician culture, differences in practice styles and the financial stability that serving a well-insured, suburban patient base provides. Physicians have adopted strategies to generate more revenue—some of which are longstanding and match their independent practice styles, while more recent strategies signal an increasing willingness to partner with other physicians and hospitals.

Some physicians in northern New Jersey are able to earn more by not contracting with health insurers. To avoid administrative hassles and payment delays, some established PCP practices in suburban areas operate cash-only practices, requiring patients to pay up front, but depending on the type of insurance they have, receive partial reimbursement from their insurer. Some surgical specialists also attract sufficient numbers of patients and higher reimbursement without joining health plan provider networks, even though northern New Jersey is “densely populated with specialists, making it a very competitive environment,” as one observer said.

New Jersey physicians face somewhat unusual incentives to remain outside of health plan networks. State law requires insurers to pay physicians out-of-network rates that generally exceed the rates paid to plans’ contracted physicians. For example, the state requires insurers in the small group and individual markets to reimburse out-of-network physicians at the 80th percentile of prevailing billed charges in the area, which is significantly higher than the rates network physicians typically receive. Although insurance carriers for private employers with more than 50 employees do not face such requirements, state and school employee benefits programs are required to pay physicians at the 90th percentile of prevailing charges.

Health plan concerns about the prevalence and cost of out-of-network care likely will be exacerbated in 2011, when a new assignment-of-benefits law goes into effect in New Jersey. The new law is the culmination of a protracted legal dispute between health care providers and Horizon BCBS, which had contractually prohibited its enrollees from assigning benefit payments to out-of-network providers. Instead, Horizon BCBS reportedly would send payments directly to patients, leaving out-of-network physicians to recover payment from patients who did not pay for care up front. The new law allows patients to assign benefits to out-of-network physicians, and if they do so, requires insurers to send payment directly to non-contracted physicians or issue joint-payee checks requiring both the provider’s and patient’s signatures. Many respondents believed the new law, coupled with the state-required payment levels for out-of-network providers, would encourage physicians to continue to decline to contract with insurers. In response, business groups and insurers have advocated for legislation to create disincentives for patients to seek care from out-of-network providers.

In the face of rising overhead costs and declining reimbursement for some specialists, there is interest among existing physician groups to expand and independent physicians to join groups. The largest private physician groups—the multispecialty Summit Medical Group and the primary care Paramount Medical Group—are recruiting physicians from within and beyond northern New Jersey. Summit has grown from 120 to 165 physicians in the last three years, has added satellite practice sites, and was in the process of hiring 20-30 additional physicians, mostly specialists. Summit has an advantage over primary care groups because it can subsidize higher PCP salaries from surpluses generated from more-lucrative specialty services. Still, increased pressures on physicians have not yet resulted in the development of new independent or hospital-based groups.

Some physicians continue to add ancillary services to their practices in direct competition to hospitals, which often provide the same services in outpatient departments. In other cases, physicians who were competing directly with hospitals for certain services now want to partner with hospitals because changes in payment rates and other factors have decreased the profitability of these services.

Summit Medical Group has expanded ancillary services, including adding an endoscopy suite and a positron emission tomography, or PET, scanner. Further, in the last three years, urologists and medical oncologists have opened large radiation-oncology ambulatory surgical centers (ASCs), particularly for prostate procedures. A spate of activity to establish ASCs occurred before September 2009, when a state moratorium on new physician-owned ASCs went into effect with the intent of limiting duplication of services. At the same time, orthopedic ASCs and freestanding cardiology centers face financial problems of aging equipment, increased competition and declining Medicare and commercial reimbursement. Both hospitals and physicians appear to be interested in partnering and forming joint ventures to provide these services.

Like individual physicians, many ASCs do not participate in health plan networks, adding to significant cost pressures for health plans. Although some health plans reported recent success in contracting with ASCs, health plan executives expressed frustration about their inability to reduce the number of providers practicing outside of insurance networks and curb enrollees’ use of out-of-network providers. Horizon BCBS recently settled a class-action lawsuit with approximately 130 ASCs, which claimed the insurer underpaid them for out-of-network care provided to the plan’s enrollees.

Pressure on Insurers to Control Costs

![]() orthern New Jersey residents—particularly the many covered by larger employers—have enjoyed relatively comprehensive health benefits with broad choice of providers and low patient cost sharing. Given this demand for rich benefits, there has been little differentiation among the four major health plans or innovation to offer lower-cost options. Plans typically offer insurance products—the preferred provider organization (PPO) model is increasingly dominant—with similar provider networks. In contrast, more-price-conscious smaller employers have adopted lower-cost products—such as health maintenance organizations (HMOs) and other more restrictive products that expose consumers to higher out-of-pocket costs.

orthern New Jersey residents—particularly the many covered by larger employers—have enjoyed relatively comprehensive health benefits with broad choice of providers and low patient cost sharing. Given this demand for rich benefits, there has been little differentiation among the four major health plans or innovation to offer lower-cost options. Plans typically offer insurance products—the preferred provider organization (PPO) model is increasingly dominant—with similar provider networks. In contrast, more-price-conscious smaller employers have adopted lower-cost products—such as health maintenance organizations (HMOs) and other more restrictive products that expose consumers to higher out-of-pocket costs.

However, rising health care costs and recessionary pressures have led employers to gradually shift more health insurance costs to their workers and to start seeking lower-cost product designs. Over a number of years, employees at large firms have seen PPO coinsurance rates increase from typically 10 percent to 20 percent for in-network care and deductibles increase to $300-$400. Workers at small firms also have experienced rising cost sharing.

In addition, both very small and very large employers are offering consumer-driven health plans (CDHPs) that include larger deductibles and options for a health savings account or health reimbursement arrangement. Smaller employers typically offer CDHPs to replace other insurance products, while larger employers offer CDHPs as an option alongside other types of plans. Most of the CDHP offerings include first-dollar coverage for preventive services. CDHPs still comprise only a small percentage of the market.

Some employers are considering adopting product designs that restrict provider choice in exchange for lower costs, such as narrow networks and tiered-provider networks, but these products have yet to emerge. As a health plan marketing executive acknowledged, “What you hear if you go out in to the market is frustration that almost everyone [health plans and products] looks like vanilla.” Although health plans have lower-cost products with slightly narrower physician networks—for instance, UnitedHealth Group’s Liberty network includes the same hospitals but only three-quarters of the physicians in its Freedom network—they are not considered restrictive enough to offer significant cost savings.

The relative leverage of the suburban hospital systems and some physicians over rate negotiations and provider decisions about network participation have limited health plans’ ability to control rising premiums. Rate negotiations between Horizon BCBS, the largest plan in the market, and providers reportedly are contentious and growing more so. One health plan executive said hospitals often begin negotiations by threatening to terminate their contract. Summit Medical Group and Newton Memorial Hospital do not contract with Horizon BCBS, and independent Mountainside Hospital in suburban Montclair recently terminated its contract with Aetna. However, at least one health plan has found some physicians are deciding to join provider networks in light of concern that the incentives to remain out of network may not last.

Growing Interest in Wellness Programs

![]() s in many communities, interest in employee wellness programs has been growing in northern New Jersey, particularly among larger employers looking for strategies to control longer-term cost growth. Some large employers offering these programs are incorporating financial incentives for employees to complete health risk assessments and, less often, to participate in programs that include biometric screenings, education and behavior modification programs, such as smoking cessation and weight management. The prevalence and comprehensiveness of wellness programs increase with employer size. Also, a few employers are beginning to use financial penalties for noncompliance, such as higher cost sharing, and to tie incentives more directly to employees achieving certain health benchmarks. Health plans’ wellness offerings for smaller employers tend to be more limited.

s in many communities, interest in employee wellness programs has been growing in northern New Jersey, particularly among larger employers looking for strategies to control longer-term cost growth. Some large employers offering these programs are incorporating financial incentives for employees to complete health risk assessments and, less often, to participate in programs that include biometric screenings, education and behavior modification programs, such as smoking cessation and weight management. The prevalence and comprehensiveness of wellness programs increase with employer size. Also, a few employers are beginning to use financial penalties for noncompliance, such as higher cost sharing, and to tie incentives more directly to employees achieving certain health benchmarks. Health plans’ wellness offerings for smaller employers tend to be more limited.

Health plans are positioning themselves to meet employer demand for more robust wellness programs. Plans reported integrating health promotion and wellness programs with disease management and case management programs to address a range of needs from healthy individuals to people with multiple chronic conditions. Health plans or vendors have started to use health risk assessments, biometric screenings and claims data to determine where along the continuum a member falls and to tailor the member’s program. At the same time, benefits consultants raised questions about the effectiveness and value offered by certain disease management programs, reporting that some employers were paring back programs. As one benefits consultant said, “If you are spending $2-$4 per employee per month and not seeing a return on investment than you will drop [the program].” A health plan executive confirmed that employers were asking for more information about the return on investment for these programs.

Safety Net Focuses on Primary Care

![]() hile the safety net for low-income people in northern New Jersey historically has been sparse and fragmented, access to primary care has improved in recent years amid signs of increasing collaboration among providers. University Hospital has long been a major provider of primary care, but the volume of patients seeking care increasingly exceeds capacity. To augment the safety net, the number of federally qualified health center facilities has increased with federal and state financial support—FQHC status affords direct federal grant funding as well as enhanced Medicaid reimbursement. Today, the northern New Jersey market has three main FQHCs that largely serve distinct geographic areas: Newark Community Health Center (Newark CHC), with six sites in Essex County; Zufall Health Center, with two sites in Morris County; and Neighborhood Health Services, with five sites in Union and Sussex counties. The Newark Health Department also provides primary care and a federal health care program for the homeless.

hile the safety net for low-income people in northern New Jersey historically has been sparse and fragmented, access to primary care has improved in recent years amid signs of increasing collaboration among providers. University Hospital has long been a major provider of primary care, but the volume of patients seeking care increasingly exceeds capacity. To augment the safety net, the number of federally qualified health center facilities has increased with federal and state financial support—FQHC status affords direct federal grant funding as well as enhanced Medicaid reimbursement. Today, the northern New Jersey market has three main FQHCs that largely serve distinct geographic areas: Newark Community Health Center (Newark CHC), with six sites in Essex County; Zufall Health Center, with two sites in Morris County; and Neighborhood Health Services, with five sites in Union and Sussex counties. The Newark Health Department also provides primary care and a federal health care program for the homeless.

FQHCs also have grown in response to the loss of outpatient care in neighborhoods where safety net hospitals have closed. The closure of Columbus and Saint James hospitals in 2008 sparked new safety net collaborations. Although many safety net leaders agreed the city had excess inpatient capacity, they pushed for a continuation of primary care in the neighborhoods surrounding the closed hospitals. Newark CHC expanded operations to provide primary care and other outpatient services at closed hospital facilities in Orange and Irvington and is doing the same at Columbus and Saint James.

City and safety net leaders now meet frequently to discuss safety net issues and strategies. They recently formed a nonprofit organization—the Greater Newark HealthCare Coalition—to work on a more comprehensive plan for the safety net, with a focus on creating formal medical homes, improving care coordination, and attracting and retaining more PCPs.

Also, given growing numbers of low-income people in the suburbs, FQHCs have expanded into suburban areas. For example, Zufall started as a free clinic in the low-income, working-class community of Dover in Morris County but became an FQHC in 2004 and more recently qualified to add a site in Morristown—an otherwise wealthy community where pockets of poverty have emerged. Zufall also has a mobile van to provide preventive and dental services in outlying areas—particularly Hunterdon County, which lacks health centers.

The safety net hospitals and health centers are serving more and more patients, primarily stemming from patients displaced by hospital closures and additional lower-to-middle income patients who lost their jobs and health insurance during the recession. Also, capacity expansions have allowed FQHCs to treat more low-income patients who may not have had a primary care provider in the past. Over the past three years, Zufall’s patient volumes have doubled and Newark CHC’s have increased 20 percent. FQHCs also are providing access to services typically difficult for low-income people to obtain by adding dental capacity and addressing behavioral health needs within primary care visits. University Hospital’s ambulatory care clinics have been unable to keep up with increased demand; their patient volume actually declined given inadequate numbers of practitioners and reduced productivity associated with implementing an EMR. However, the clinics are undergoing significant redesign of administrative and clinical processes in an effort to improve efficiency and capacity.

Also, some FQHCs are working more collaboratively with safety net hospitals to help patients obtain needed services in the most appropriate and cost-effective setting. For example, Newark CHC and Newark Beth Israel Medical Center have partnered on several projects. The health center refers patients to Newark Beth Israel for cardiology and inpatient needs—obstetrics in particular. More recently, the two providers have created processes to allow ED staff to schedule patients with non-urgent conditions at the health center.

State Focuses on Covering Children; Adults Lose Ground

![]() ew Jersey is among the most generous states in providing insurance coverage through public programs, particularly for children. The state’s Children’s Health insurance Program (CHIP), NJ FamilyCare, covers children in families with incomes up to 350 percent of federal poverty, or $77,175 annually for a family of four in 2010. Children in families with incomes above 200 percent of poverty pay a portion of the premium cost, and those in families with incomes above 350 percent of poverty can pay the full premium for comparable benefits through the separate NJ FamilyCare Advantage program.

ew Jersey is among the most generous states in providing insurance coverage through public programs, particularly for children. The state’s Children’s Health insurance Program (CHIP), NJ FamilyCare, covers children in families with incomes up to 350 percent of federal poverty, or $77,175 annually for a family of four in 2010. Children in families with incomes above 200 percent of poverty pay a portion of the premium cost, and those in families with incomes above 350 percent of poverty can pay the full premium for comparable benefits through the separate NJ FamilyCare Advantage program.

In response to relatively low enrollment of children in Medicaid and CHIP, the state has pushed to identify and enroll eligible children. In 2008, the state mandated that all children have insurance coverage, although there is no penalty for noncompliance. The state has intensified outreach activities and streamlined application processes, which market observers considered successful overall. The Kaiser Family Foundation reported that New Jersey’s CHIP enrollment increased 10.1 percent from March 2008 to March 2009, significantly more than the 2 percent growth nationally. However, take up in the Advantage program has been quite low to date, which observers attributed to the premium cost and lack of marketing by Horizon BCBS, the sole carrier.

The state traditionally has covered low-income parents and legal immigrants. However, eligibility for parents and adult immigrants has waxed and waned over the past decade, depending on the state’s ability to fund coverage. Significant state budget deficits led to a spring 2010 freeze on enrollment for parents with incomes between 133 percent and 200 percent of poverty and for adult immigrants—immigrant children remain covered. The state is working to connect these newly uninsured individuals with FQHCs to ensure they continue to receive outpatient care. Also, some observers expressed concern that removing eligibility for parents will erode some of the gains in enrolled children as the two have been found to be correlated.

Despite large state budget deficits, the Medicaid program has been largely protected from cuts. Acceptance of federal stimulus funding prevented any reductions in Medicaid eligibility, and the state has preserved optional benefits and does not require copayments from Medicaid and lower-income CHIP enrollees. However, safety net respondents lamented cuts in family planning services, and some state lawmakers hoped to reverse the reductions.

Yet, access to physicians remains difficult for people covered by public insurance. New Jersey Medicaid physician reimbursement rates are among the lowest in the country. Although the state more than tripled fee-for-service payment rates for pediatric services in 2008—bringing them to approximately 80 percent of Medicare rates—it is less clear how payment and access have changed for Medicaid enrollees in managed care arrangements. Although growth of FQHCs has helped improve access to primary care physicians, declining PCP supply may cause workforce shortages for health centers as well as more broadly.

Most people covered by Medicaid and CHIP are enrolled in managed care, which the state contends improves access, although safety net providers noted limitations in the provider networks and frequent changes in physician participation. The state currently contracts with four health plans for Medicaid and FamilyCare: Horizon BCBS has the largest market share; followed by AmeriChoice of New Jersey, which is owned by UnitedHealth Group; AMERIGROUP, a multi-state for-profit plan; and Healthfirst, a provider-sponsored plan based in New York City. There have been some entries and exits of Medicaid managed care plans in recent years, but movement to new plans reportedly had little impact on enrollees.

Anticipating Health Reform

![]() verall, health care leaders in northern New Jersey were enthusiastic about health reform under the federal Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA). FQHCs are receiving additional federal funding under PPACA, with Newark CHC receiving a grant to double its Newark facility and renovate another site. Health plans and providers believe they will benefit from more insured enrollees and patients, and some observers suggested that health plans and employers will adopt new health insurance benefit structures.

verall, health care leaders in northern New Jersey were enthusiastic about health reform under the federal Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA). FQHCs are receiving additional federal funding under PPACA, with Newark CHC receiving a grant to double its Newark facility and renovate another site. Health plans and providers believe they will benefit from more insured enrollees and patients, and some observers suggested that health plans and employers will adopt new health insurance benefit structures.

To address the need for further consolidation and less duplication of services, plans and providers expressed interest in developing accountable care organizations (ACOs) that are envisioned as bringing hospitals, physicians and other providers together to improve the quality and efficiency of care for a defined patient population. Atlantic Health recently announced its launch of an ACO that will begin enrolling patients in January 2012. However, few respondents could provide detail on the shape ACOs would take, and the lack of significant alignment between hospitals and physicians likely will pose challenges.

In an effort to control costs in collaboration with providers, Horizon BCBS launched a new company, called Horizon Healthcare Innovations, in the summer of 2010, partially in response to the passage of health reform. The company is working with physicians, hospitals and others to experiment with various care delivery and payment strategies to reduce unnecessary service use and generate better outcomes for patients, by implementing pilot programs on patient-centered medical homes, ACOs and defining episodes of care.

Some Medicaid providers are in the early stages of medical-home initiatives, and a few physician practices are involved in the Horizon BCBS medical-home pilot that includes collaboration with the New Jersey Academy of Family Physicians.

However, providers expressed concern about reimbursement levels, including reductions in the growth of Medicare payment rates and continued low Medicaid payment rates. New Jersey currently enjoys relatively high disproportionate share hospital (DSH) funding compared to other states, so has more to lose through the planned reductions to DSH funding that would especially affect the state’s hospital charity care program. Observers worried about having sufficient charity care funding to subsidize the costs of caring for the remaining uninsured—a particular issue in this market given the sizable immigrant population.

Additionally, market observers worried that the primary care physician workforce would be insufficient as the insured population grows.

Issues to Track

Background Data

| Northern New Jersey Demographics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Northern New Jersey Metropolitan Area | Metropolitan Areas 400,000+ Population | |

| Population, 20091 | 2,126,269 | |

| Population Growth, 5-Year, 2004-20092 | 0.1% | 5.5% |

| Age3 | ||

| Under 18 | 24.4% | 24.8% |

| 18-64 | 63.4% | 63.3% |

| 65+ | 12.2% | 11.9% |

| Education3 | ||

| High School or Higher | 86.7% | 85.4% |

| Bachelor’s Degree or Higher | 35.9% | 31.0% |

| Race/Ethnicity4 | ||

| White | 56.4% | 59.9% |

| Black | 20.8% | 13.3% |

| Latino | 16.7% | 18.6% |

| Asian | 5.0% | 5.7% |

| Other Races or Multiple Races | 1.2% | 4.2% |

| Other3 | ||

| Limited/No English | 13.2% | 10.8% |

Sources: 1 U.S. Census Bureau, Annual Population Estimate, 2009 2 U.S. Census Bureau, Annual Population Estimate, 2004 and 2009 2 U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2008 3 U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2008, weighted by U.S. Census Bureau, Annual Population Estimate, 2008 |

||

| Economic Indicators | ||

|---|---|---|

| Northern New Jersey Metropolitan Area | Metropolitan Areas 400,000+ Population | |

| Individual Income less than 200% of Federal Poverty Level1 | 21.5% | 26.3% |

| Household Income more than $50,0001 | 64.5% | 56.1% |

| Recipients of Income Assistance and/or Food Stamps1 | 6.1% | 7.7% |

| Persons Without Health Insurance1 | 13.6% | 14.9% |

| Unemployment Rate, 20082 | 5.4% | 5.7% |

| Unemployment Rate, 20093 | 9.0% | 9.2% |

| Unemployment Rate, March 20104 | 9.5% | 9.6% |

Sources: |

||

| Health Status1 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Northern New Jersey Metropolitan Area | Metropolitan Areas 400,000+ Population | |

| Chronic Conditions | ||

| Asthma | 12.8% | 13.4% |

| Diabetes | 7.7% | 8.2% |

| Angina or Coronary Heart Disease |

4.0% | 4.1% |

| Other | ||

| Overweight or Obese | 61.2% | 60.2% |

| Adult Smoker | 13.0% | 18.3% |

| Self-Reported Health Status Fair or Poor |

14.4% | 14.1% |

Sources: |

||

| Health System Characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Northern New Jersey Metropolitan Area |

Metropolitan Areas 400,000+ Population | |

| Hospitals1 | ||

| Staffed Hospital Beds per 1,000 Population | 2.6 | 2.5 |

| Average Length of Hospital Stay (Days) | 5.7 | 5.3 |

| Health Professional Supply | ||

| Physicians per 100,000 Population2 | 268 | 233 |

| Primary Care Physicians per 100,000 Poplulation2 | 93 | 83 |

| Specialist Physicians per 100,000 Population2 | 175 | 150 |

| Dentists per 100,000 Population2 | 81 | 62 |

Average monthly per-capita reimbursement for beneficiaries enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare3 |

$755 | $713 |

# Indicates a 12-site low. Sources:1 American Hospital Association, 2008 2 Area Resource File, 2008 (includes nonfederal, patient care physicians) 3 HSC analysis of 2008 county per capita Medicare fee-for-service expenditures, Part A and Part B aged and disabled, weighted by enrollment and demographic and risk factors. See www.cms.gov/MedicareAdvtgSpecRateStats/05_FFS_Data.asp. |

||

Community Reports are published by the Center for Studying

Health System Change:

600 Maryland Avenue, SW, Suite 550

Washington, DC 20024-2512

Tel: (202) 484-5261

Fax: (202) 484-9258

www.hschange.org

President: Paul B. Ginsburg