Community Report No. 6

February 2011

Ann S. O'Malley, Grace Anglin, Amelia M. Bond, Peter J. Cunningham, Lucy B. Stark, Tracy Yee

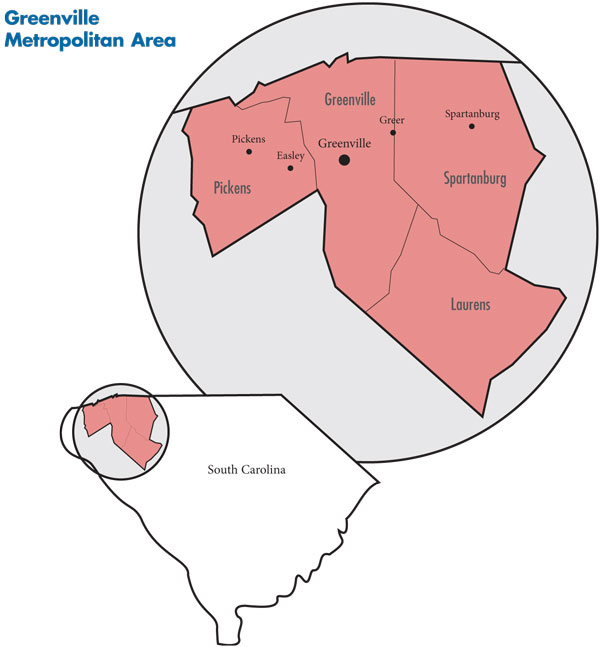

In July 2010, a team of researchers from the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC), as part of the Community Tracking Study (CTS), visited the Greenville-Spartanburg metropolitan area to study how health care is organized, financed and delivered in that community. Researchers interviewed more than 45 health care leaders, including representatives of major hospital systems, physician groups, insurers, employers, benefits consultants, community health centers, state and local health agencies, and others. The Greenville-Spartanburg metropolitan area encompasses Greenville, Laurens, Pickens and Spartanburg counties.

In a market already notable for high rates of physician employment, the two largest hospital systems, Greenville Hospital System University Medical Center (GHS) and Spartanburg Regional, have greatly increased employment of physicians in recent years. The hospital systems are employing more physicians, particularly primary care physicians, with an eye toward capturing referrals and admissions, especially in the growing community of Greer where both major systems are vying for dominance.

While the hospital systems predict improvements in care coordination, quality and safety, others are concerned that increased hospital-physician alignment may give the systems greater leverage to negotiate higher payment rates from health plans, resulting in higher health care costs. And, the increased integration of physicians and hospitals means access to care can change markedly for patients when provider-plan disputes disrupt provider networks.

Key developments include:

- Population Growth Amid Economic Pressures

- Weak Economy Pressures Hospitals

- Hospitals Compete Locally, but Keep an Eye on Outsiders

- Hospital Employment of Physicians Surges

- Impact of Physician Employment

- BCBS-SC Maintains Dominance

- Little Left to Squeeze from Benefit Design

- Stable Safety Net Stressed by Slow Economy

- Anticipating Health Reform

- Issues to Track

- Background Data

Population Growth Amid Economic Pressures

![]() ueled by the lure of manufacturing jobs and an influx of retirees, the population of the Greenville-Spartanburg metropolitan area (see map below) is approaching 1 million people and continues to grow rapidly—9.5 percent between 2004 and 2009—almost twice as fast as other large metropolitan areas. Bordering North Carolina, the Greenville-Spartanburg metropolitan area is part of South Carolina’s “Upstate” region, a 10-county area in the northwest part of the state. Greenville is the largest city in the metropolitan area, followed by Spartanburg. The city of Greer straddles the boundary line of Greenville and Spartanburg counties and has a growing, more-affluent population.

However, on average, Greenville-Spartanburg area residents are less affluent, have slightly less formal education, poorer health status and are more likely to lack health insurance—17.2 percent uninsured vs. the 14.9 percent average for large metropolitan areas in 2008.

ueled by the lure of manufacturing jobs and an influx of retirees, the population of the Greenville-Spartanburg metropolitan area (see map below) is approaching 1 million people and continues to grow rapidly—9.5 percent between 2004 and 2009—almost twice as fast as other large metropolitan areas. Bordering North Carolina, the Greenville-Spartanburg metropolitan area is part of South Carolina’s “Upstate” region, a 10-county area in the northwest part of the state. Greenville is the largest city in the metropolitan area, followed by Spartanburg. The city of Greer straddles the boundary line of Greenville and Spartanburg counties and has a growing, more-affluent population.

However, on average, Greenville-Spartanburg area residents are less affluent, have slightly less formal education, poorer health status and are more likely to lack health insurance—17.2 percent uninsured vs. the 14.9 percent average for large metropolitan areas in 2008.

In contrast to the manufacturing decline in many other communities, Greenville-Spartanburg has a vibrant manufacturing sector, including Michelin North America and BMW Corp. According to the Census Bureau’s 2008 American Community Survey, manufacturing jobs accounted for about 20 percent of the local economy compared with 11 percent nationally. Part of the area’s appeal to manufacturers is that South Carolina is a “right-to-work” state, resulting in few labor unions, which makes it easier for employers to constrain wages and health care benefits.

Still, the recession hit the area earlier and harder than elsewhere, with the local unemployment rate almost two percentage points higher than the national average in 2009—11.1 percent vs. 9.3 percent. The Greenville-Spartanburg unemployment rate had declined to 10.5 percent in July 2010, compared to 9.7 percent nationally. Despite an increase in some private-sector jobs recently—BMW added 600 jobs at its Greer plant in October 2010—the economy reportedly is still weak overall and recovering slowly.

Greenville Hospital System University Medical Center and Spartanburg Regional are the largest hospital systems in the market. There are two smaller hospital systems: Bon Secours St. Francis Health System, which has two hospitals in Greenville—St. Francis Downtown and St. Francis Eastside—and is part of the larger multi-state Catholic Bon Secours Health System; and Spartanburg-based Mary Black Health System, which was purchased in 2007 by Community Health Systems, a Tennessee-based, for-profit company whose affiliates own, lease or operate more than 126 hospitals in 29 states.

While a small proportion of physicians remain independent, the majority of physicians are now employed by one of the hospital systems.

In Greenville and Spartanburg, the outpatient safety net includes a federally qualified health center (FQHC) and free clinics in each county. Inpatient safety net care is provided primarily by GHS and Spartanburg Regional with smaller amounts provided by St. Francis and Mary Black hospitals.

The insurance market is highly concentrated, with BlueCross BlueShield of South Carolina estimated to hold about 60 percent of the commercial market, followed by national carriers CIGNA and UnitedHealth Group. Aetna also has a small presence in the market, along with Carolina Care, which focuses primarily on the individual and small group markets and is owned by Medical Mutual of Ohio.

Weak Economy Pressures Hospitals

![]() hen characterizing the area, most respondents separated the Greenville-Spartanburg market into two submarkets: Greenville, Pickens and Laurens counties in one and Spartanburg County in the other. Other than in Greer, where both Greenville Hospital System and Spartanburg Regional have hospitals and other facilities, there is little overlap between the two large systems.

hen characterizing the area, most respondents separated the Greenville-Spartanburg market into two submarkets: Greenville, Pickens and Laurens counties in one and Spartanburg County in the other. Other than in Greer, where both Greenville Hospital System and Spartanburg Regional have hospitals and other facilities, there is little overlap between the two large systems.

According to respondents, GHS and Spartanburg Regional each have about 70 percent market share—combined inpatient and outpatient—in their respective submarkets. GHS has five acute care hospitals in the market, including the flagship, 735-bed Greenville Memorial Hospital. Spartanburg Regional has two acute care hospitals in the metropolitan area—Spartanburg Regional Medical Center with 500-plus beds and the 48-bed Village Hospital in Greer.

In addition to the two large systems, a smaller hospital system operates in each submarket: Bon Secours St. Francis Health System in Greenville and Mary Black Health System in Spartanburg.

All hospital respondents pointed to the weak economy as their biggest pressure. They reported seeing more uninsured patients who have lost coverage because of job losses and more Medicaid patients, whose reimbursement is lower than privately insured patients. Some also reported that private insurer payment rate increases have not kept up with their unit cost growth. Compared with smaller hospitals, the larger hospital systems have more negotiating leverage with commercial insurers and are reportedly able to obtain payment rates that cover cost increases, but their operating margins are narrower than in the past, suggesting they have lost ground.

Hospitals Compete Locally, but Keep an Eye on Outsiders

![]() hile the Greenville-Spartanburg area has about the same number of hospital beds per 1,000 residents (2.4 in 2008) as other large metropolitan areas, many respondents believed there is excess inpatient capacity, contributing to hospital competition within submarkets. Partly in anticipation of continuing rapid population growth, the two major systems have built new hospitals in Greer. GHS opened Greer Memorial in 2008, which replaced Allen Bennett Hospital, while Spartanburg Regional owns Village Hospital. In Greer, competition between GHS and Spartanburg Regional centers on oncology, ambulatory surgeries and procedures, and emergency department services.

hile the Greenville-Spartanburg area has about the same number of hospital beds per 1,000 residents (2.4 in 2008) as other large metropolitan areas, many respondents believed there is excess inpatient capacity, contributing to hospital competition within submarkets. Partly in anticipation of continuing rapid population growth, the two major systems have built new hospitals in Greer. GHS opened Greer Memorial in 2008, which replaced Allen Bennett Hospital, while Spartanburg Regional owns Village Hospital. In Greer, competition between GHS and Spartanburg Regional centers on oncology, ambulatory surgeries and procedures, and emergency department services.

In hopes of becoming the dominant regional referral center for specialized services for the entire Upstate, GHS strives to attract patients from outside Greenville County. In 2009, GHS purchased 50 percent of Palmetto Health’s Baptist Easley Hospital in Pickens County, west of Greenville. At the same time that GHS is expanding its reach, the system also is concerned about deterring competitors from entering the Greenville-Spartanburg market.

There are several large hospital systems operating just outside the market that are potential threats. In what was perceived as a direct response to GHS’s partial acquisition of Baptist Easley Hospital, Charlotte, N.C.-based Carolinas HealthCare System in 2009 affiliated with AnMed Health in Anderson, S.C., southwest of Greenville, and Cannon Memorial Hospital in Pickens, just west of Greenville. Another large system, Novant Health, also based in North Carolina, has a hospital in Gaffney, S.C., just east of Spartanburg in Cherokee County, as well as 11 hospitals in Virginia and North Carolina.

A notable exception to the continued hospital system competition has been increased collaboration between Greenville and Spartanburg on pediatric care because neither community has a sufficient child and adolescent population to support pediatric subspecialties. For some pediatric subspecialty services and pediatric inpatient care, Spartanburg Regional refers many children to GHS.

Hospital Employment of Physicians Surges

![]() ospitals have sharply increased physician hiring in recent years, especially primary care physicians (PCPs) and specialists to support select service-line expansions. A hospital executive’s comment captured the sentiment of most respondents, “There is a mad grab to hire PCPs.” Historically, the Greenville-Spartanburg area has had relatively high levels of physician employment by hospitals compared to other markets. In the 1990s, hospitals increased hiring of primary care physicians during the managed care era, but when opportunities for risk contracting failed to materialize because of low enrollment in health maintenance organization (HMO) products, hiring of primary care physicians slowed.

ospitals have sharply increased physician hiring in recent years, especially primary care physicians (PCPs) and specialists to support select service-line expansions. A hospital executive’s comment captured the sentiment of most respondents, “There is a mad grab to hire PCPs.” Historically, the Greenville-Spartanburg area has had relatively high levels of physician employment by hospitals compared to other markets. In the 1990s, hospitals increased hiring of primary care physicians during the managed care era, but when opportunities for risk contracting failed to materialize because of low enrollment in health maintenance organization (HMO) products, hiring of primary care physicians slowed.

However, given GHS’s need to support a graduate medical education program, GHS in particular did not retreat from the employed physician model. In the late-1990s, many hospital-employed physicians in the market began moving from a salaried model to a productivity model mimicking private practice, which helped maintain physician productivity. Throughout the past decade, specialist hiring has continued to increase steadily.

In the last three years, GHS, including its faculty practice—University Medical Group—has increased the number of employed physicians from about 160 to more than 550. GHS now employs five times the number of physicians employed a decade ago and projects additional hires in the coming years. Spartanburg Regional now employs about 270 physicians, up from about 180 physicians three years ago. Spartanburg Regional also owns 51 percent of a clinically integrated physician hospital organization (PHO), known as Regional HealthPlus. The PHO is an additional vehicle for hospital-physician alignment and can jointly contract with health plans on behalf of its physicians—both the 270 employed by Spartanburg Regional and 200 independent community physicians—and hospitals. The smaller St. Francis system also has increased physician employment dramatically since 2005 to about 180 physicians in 2010. In contrast to other systems, Mary Black Health System severed employment relationships with many specialists, resulting in movement of some market share from Mary Black to Spartanburg Regional. Several respondents estimated that about 90 percent of physicians in Greenville and about 60 percent in Spartanburg are now employed by hospital systems.

The stepped-up employment of primary care physicians highlights hospitals’ efforts to gain market share, feed referrals to employed specialists, capture admissions, and position themselves for expected changes in payment methods away from fee-for-service reimbursement toward more global or bundled payment under health care reform.

In an effort to further develop and align physicians with their institutions, hospitals are also training more physicians within their systems. Both GHS and Spartanburg Regional have enhanced or created relationships with medical schools. The University of South Carolina (USC) plans to expand its current third- and fourth-year program at GHS to a full four-year program with 100 students in the graduating class by 2020. This school will be a separately accredited program known as the USC School of Medicine – Greenville. Spartanburg Regional will act as the host hospital for the new Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine – Carolinas Campus.

Physicians continue to sign on to the hospital-employment model for various reasons, including maintaining their patient base, improving reimbursement and rising costs of practice. In terms of patient base, many feel a fear of being “left out of the market” as hospitals hire more physicians. Stagnant reimbursement rates and weak leverage to negotiate payment rates with health plans as independent physicians add to the pressures of growing overhead expenses, particularly for PCPs. Independent PCPs also noted the challenge of having to compete for employees—new physicians and staff—with the larger hospital systems. Lastly, physicians of all specialties are concerned about malpractice premiums and find some security as employees of large systems.

A few independent physicians remain in the Greenville market, some of whom are specialists—for example, urologists, neurosurgeons, ophthalmologists—and a small proportion of PCPs. A large gastroenterology group formed from two smaller groups as an alternative to hospital acquisition. There also is an independent, 14-physician multispecialty group in Spartanburg called Carolina Medical Affiliates, which has existed for 40 years. The area has no large independent multispecialty groups and no independent practice associations.

Impact of Physician Employment

![]() ith high levels of physician employment by hospitals, changes in hospital systems and their participation in health plan provider networks can impact large numbers of patients. Physician employment by hospitals theoretically can result in increased clinical integration and coordination for patients. According to several market observers, employed physicians increasingly are expected to keep admissions and referrals within their hospital systems. When various providers caring for a patient work in the same system, ideally, there would be better coordination of care. Initially, however, some independent physicians noted some longstanding patient-physician relationships, especially with specialists unaffiliated with a particular system, have been disrupted. Additional potential benefits of physician-hospital alignment include the system’s ability to influence and support clinician practice. In addition, Medicaid and uninsured patients may have better access to specialists when they are employed by a system.

ith high levels of physician employment by hospitals, changes in hospital systems and their participation in health plan provider networks can impact large numbers of patients. Physician employment by hospitals theoretically can result in increased clinical integration and coordination for patients. According to several market observers, employed physicians increasingly are expected to keep admissions and referrals within their hospital systems. When various providers caring for a patient work in the same system, ideally, there would be better coordination of care. Initially, however, some independent physicians noted some longstanding patient-physician relationships, especially with specialists unaffiliated with a particular system, have been disrupted. Additional potential benefits of physician-hospital alignment include the system’s ability to influence and support clinician practice. In addition, Medicaid and uninsured patients may have better access to specialists when they are employed by a system.

However, many respondents noted that moving to an employed model does not necessarily result in well-coordinated care for patients. In many cases, the hospital systems are struggling to develop clinical-care processes and practice tools needed to support coordinated patient care. For example, similar to hospitals in other markets, both GHS and Spartanburg Regional each use different inpatient and outpatient electronic health records that are not interoperable. On the outpatient side, about half of GHS faculty practice physicians are on the same electronic health record. One physician captured the sentiment of many that “coordination is a struggle” and that “we need tools to make it better.” Most respondents indicated effective coordination remains a challenge and will take time.

At the same time, greater hospital-physician alignment, particularly under fee-for-service reimbursement, carries risks. The greater negotiating leverage of aligned providers over health plans can lead to increased overall costs through higher payment rates. Increased provider alignment also can affect patient access to care when contracts between large hospital systems and payers are not renewed, disrupting the plan’s provider network. For example, enrollees of Select Health—at the time, the largest Medicaid managed care plan in Greenville—lost access to GHS hospitals and physicians in February 2010 when the system pulled out of the plan’s provider network over a payment rate dispute. Given that GHS provides the bulk of pediatric inpatient and subspecialty care in the market, Select Health pediatric patients now are referred to Charlotte or Columbi——both approximately 90 miles from Greenville—for care. Respondents noted that the break between Select Health and GHS has affected independent physicians’ ability to refer to GHS doctors and increased administrative burden in their offices to secure alternate referrals for Select Health enrollees.

BCBS-SC Maintains Dominance

![]() he major commercial insurers—BlueCross BlueShield of South Carolina, UnitedHealth Group, CIGNA—have similar provider networks, which typically include all four hospital systems. Still, the Blue plan continues to dominate, with an estimated 60 percent of the commercial market and the ability to obtain better provider discounts than smaller plans.

he major commercial insurers—BlueCross BlueShield of South Carolina, UnitedHealth Group, CIGNA—have similar provider networks, which typically include all four hospital systems. Still, the Blue plan continues to dominate, with an estimated 60 percent of the commercial market and the ability to obtain better provider discounts than smaller plans.

Insurers reported growing difficulty containing provider rate increases given the increasing degree of hospital-physician consolidation in the market. One insurer noted changes in billing among hospital systems where physician visits in hospital-owned, community-based practices are billed as a hospital outpatient department visit, resulting in an additional facility fee, along with the physician’s professional services fee. The practice contributes to higher costs for both patients and health plans. According to insurers, the tremendous increase in hospitals buying physician practices has reduced provider competition and increased overall costs.

From the hospital perspective, the additional payments are justified because hospitals face “higher depreciation costs and physician ramp-up costs,” such as ensuring a new physician’s salary until they build up a patient panel. While newly owned physician practices “are not fully productive right out of the gate,” overall hospitals believe their hiring strategies make sense in the longer term.

Little Left to Squeeze from Benefit Designs

![]() tarting from a historical base of less-comprehensive benefits, South Carolina employers are looking for options to save on health care costs. A broker commented, “Creativity must come into play because we have squeezed all we can out of the less-rich designs.” In addition, the large blue-collar and manufacturing base, combined with the lack of unions, are factors in South Carolina employees bearing more patient cost sharing. The area’s higher-than-average unemployment rate during the recession and the resulting loss of health insurance has exacerbated the situation. In South Carolina overall, small employers are less likely than small employers nationwide to offer health insurance. In light of these factors, employers increasingly are anxious to find ways to contain costs and maintain some level of health coverage.

tarting from a historical base of less-comprehensive benefits, South Carolina employers are looking for options to save on health care costs. A broker commented, “Creativity must come into play because we have squeezed all we can out of the less-rich designs.” In addition, the large blue-collar and manufacturing base, combined with the lack of unions, are factors in South Carolina employees bearing more patient cost sharing. The area’s higher-than-average unemployment rate during the recession and the resulting loss of health insurance has exacerbated the situation. In South Carolina overall, small employers are less likely than small employers nationwide to offer health insurance. In light of these factors, employers increasingly are anxious to find ways to contain costs and maintain some level of health coverage.

Among employers offering health insurance, preferred provider organizations (PPOs) remain the dominant product in the Greenville-Spartanburg area, and patient cost sharing at the point of service historically has been high compared to other markets. Employers believe they have reached the limit in asking employees to take on more expenses through higher deductibles, copayments and coinsurance. Reportedly, the average deductible in commercial plans is about $1,000, and most plans offer products where patients pay 20 percent coinsurance for in-network care and 40 percent for out-of-network care. Similar to other markets, the percentage of employer premium contributions for dependent coverage has declined, reflecting another aspect of employers shifting more costs to workers.

Respondents said consumer-driven health plans (CDHPs), characterized by a high-deductible plan tied to a health savings account (HSA) or health reimbursement arrangement (HRA), are increasingly offered as an option, with some employers moving to full replacement where the CDHP is the only plan offered. United has more experience with CDHPs than other plans in the market, reportedly giving United an advantage with employers interested in CDHPs. For example, Michelin, one of the area’s largest employers, is moving from a BCBS-SC PPO plan to a United CDHP with an HRA with either a $1,000 or $2,000 deductible. While the company currently offers existing employees a choice of the traditional PPO or CDHP, all new employees are enrolled in the CDHP, and Michelin will move all employees to the CDHP in 2012.

Aside from shifting more costs to employees, some large Greenville-Spartanburg area employers are trying to contain costs with workplace clinics and wellness programs. For example, Michelin plans to open an on-site clinic, and Greenville County already has a workplace clinic with a nurse practitioner on site one day a week.

While still uncommon, a few large employers are offering value-based insurance designs (VBID). For employers, including Michelin, United offers customized plans that remove copayments for diabetes services and drugs if enrollees are compliant with their disease management program.

At the request of the state of South Carolina, BCBS-SC in 2009 introduced a VBID product for state employees focused on diabetes. Health coaches reach out to enrollees with diabetes to remind them to fill their prescriptions and obtain necessary screenings. After each quarter, if members have completed the requirements, they receive all diabetes-related drugs and services at no cost for the next quarter. BCBS-SC plans to expand the program to other conditions, including congestive heart failure, and offer the design to other employers.

Stable Safety Net Stressed by Slow Economy

![]() s is the case with other providers, the health care safety nets in Greenville and Spartanburg counties are largely separate, with little crossover in where low-income, uninsured residents receive care. The composition of both communities’ safety nets has been stable over the last few years.

s is the case with other providers, the health care safety nets in Greenville and Spartanburg counties are largely separate, with little crossover in where low-income, uninsured residents receive care. The composition of both communities’ safety nets has been stable over the last few years.

Inpatient safety net care in each submarket is provided primarily by GHS and Spartanburg Regional, respectively, with smaller amounts provided by St. Francis and Mary Black. In Greenville County, the outpatient safety net consists of one FQHC, New Horizon Family Health Services, which has 10 sites in Greenville, and two free clinics, the Greenville Free Medical Clinic and Taylors Free Medical Clinic.In Spartanburg County, there is one FQHC, ReGenesis, with four sites and one free clinic, St. Luke’s Free Medical Clinic. While the FQHCs serve both Medicaid and uninsured patients, the free clinics serve low-income, uninsured people exclusively.

Generally, safety net providers face increased demand and greater financial pressures, in large part because of the 2007-09 recession and the continuing sluggish economy. All safety net providers reported treating more uninsured patients and/or providing more charity care, largely because of higher unemployment, but also because they had expanded capacity. FQHCs also reported delays in additional state payments to make up differences between managed care plan rates and the enhanced Medicaid payments they are entitled to, resulting in cash-flow pressures.

Since the recession began in December 2007, enrollment in the state’s Medicaid program has grown by more than 100,000 people, reaching almost 850,000 people by the end of 2010. While the state received federal stimulus funding through increased Medicaid matching funds and disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments, the state Legislature depleted Medicaid trust fund reserves to cover state budget shortfalls. The depletion of Medicaid reserves, along with rapid enrollment growth, has left the state with a projected $228 million Medicaid shortfall through the end of fiscal year 2011, and a $663 million shortfall beginning July 1. Unlike other states, South Carolina is legislatively prohibited from directly reducing provider payment rates. However, the state did “rebase” payments to Medicaid managed care plans, reportedly resulting in lower provider payment rates. State Medicaid officials are trying to convince the Legislature to grant them authority to reduce provider payment rates.

Faced with stopping provider payments in March, the state Medicaid agency recently received approval from the state budget board to operate with a $100-million deficit. The state also has pared optional benefits, such as adult vision and routine dental care, but has been limited in reducing Medicaid eligibility levels by federal requirements under the federal stimulus act and now the health care reform law.

Demand Outpaces Safety Net Expansion

![]() he increase in capacity among FQHCs and free clinics has not kept pace with increased demand, which includes newly uninsured people, more uninsured with chronic conditions, and more patients with behavioral health needs because of the state closing psychiatric facilities. Federal stimulus funding allowed FQHCs to expand capacity. For example, New Horizon extended hours, restored previously cut services and hired additional staff. This capacity expansion was accompanied by 25-percent growth in visit volume. The free clinics, which were ineligible for stimulus funds, also have expanded capacity and are seeing more patients. For example, Greenville Free Clinic received a grant from BCBS-SC to add a nurse practitioner, expand dental capacity and increase clinic hours. Nonetheless, the clinic has had budget shortfalls in recent years because of increased demand and a decline in donations.

he increase in capacity among FQHCs and free clinics has not kept pace with increased demand, which includes newly uninsured people, more uninsured with chronic conditions, and more patients with behavioral health needs because of the state closing psychiatric facilities. Federal stimulus funding allowed FQHCs to expand capacity. For example, New Horizon extended hours, restored previously cut services and hired additional staff. This capacity expansion was accompanied by 25-percent growth in visit volume. The free clinics, which were ineligible for stimulus funds, also have expanded capacity and are seeing more patients. For example, Greenville Free Clinic received a grant from BCBS-SC to add a nurse practitioner, expand dental capacity and increase clinic hours. Nonetheless, the clinic has had budget shortfalls in recent years because of increased demand and a decline in donations.

Anticipating Health Reform

![]() everal state and local initiatives seek to increase coordination of care for Medicaid and uninsured patients. At the state level, the most substantial Medicaid change is the expansion of Healthy Connections Choices, a program started in October 2007 to increase enrollment in Medicaid managed care plans. Statewide enrollment in Medicaid managed care increased from about one-quarter in 2007 to about two-thirds of Medicaid enrollees eligible for managed care in 2010. The large shift was accomplished despite managed care enrollment being voluntary until Oct. 1, 2010, at which point the state made it mandatory. The increase in voluntary managed care enrollment was attributed by several respondents to the fact that Medicaid enrollees were auto-enrolled in managed care if they did not explicitly opt out.

everal state and local initiatives seek to increase coordination of care for Medicaid and uninsured patients. At the state level, the most substantial Medicaid change is the expansion of Healthy Connections Choices, a program started in October 2007 to increase enrollment in Medicaid managed care plans. Statewide enrollment in Medicaid managed care increased from about one-quarter in 2007 to about two-thirds of Medicaid enrollees eligible for managed care in 2010. The large shift was accomplished despite managed care enrollment being voluntary until Oct. 1, 2010, at which point the state made it mandatory. The increase in voluntary managed care enrollment was attributed by several respondents to the fact that Medicaid enrollees were auto-enrolled in managed care if they did not explicitly opt out.

A key part of the reform is that enrollees can choose to enroll in traditional managed care plans—in which private plans operate a provider network—or a new medical-home network that contracts directly with the state. The medical-home network is run under a contract with South Carolina Solutions, which is paid $10 per member per month by the state to maintain and support a network of primary care providers. Participating providers receive fee-for-service payments from the state and per-member, per-month payments from South Carolina Solutions to use care management guidelines. South Carolina Solutions also provides care coordination with specialists, utilization review and other support services. Several respondents reported that the medical-home network generated cost savings—relative to what Medicaid fee-for-service costs would have been—as well as favorable reviews from patients and providers. Savings are passed on to both South Carolina Solutions and to network providers. Most of the managed care enrollment has been in traditional health plans, although enrollment in the medical-home network is higher in Greenville than most other areas of the state because of GHS’s withdrawal from the Select Health provider network.

Despite the effects of the contract dispute between GHS and Select Health, access to physicians for Medicaid managed care enrollees in Greenville-Spartanburg also has been facilitated by increased hospital employment of physicians, since these physicians are included in hospital contracts with managed care plans.

There also are state and local efforts underway to increase the integration of safety net providers and coordination of care for the uninsured. Motivated in part by increasing levels of emergency department utilization, AccessHealth SC was initiated by the South Carolina Hospital Association and other stakeholders to assist communities with forming networks to provide medical homes and care coordination to low-income, uninsured people. Spartanburg was among the first communities in the state to receive an AccessHealth grant from the Duke Endowment to form a local network, and a pilot program involving 50 patients was underway at the time of the site visit. In January 2011, Greenville County also received an AccessHealth SC grant.

To be eligible for AccessHealth Spartanburg, people must be uninsured and between 18-64 years of age, have income less than 150 percent of the federal poverty level, or $16,245 for an individual in 2010, and be ineligible for other state and federal coverage. Eligible people enrolled in the program will be linked to PCPs or other medical homes. Primary care and specialist physicians in the community have been recruited to volunteer time, either without payment or at a reduced fee, to care for uninsured patients. AccessHealth will attempt to distribute uninsured patients to these physicians in a way that does not overburden individual physicians.

AccessHealth will provide both case management and care coordination services to patients. Inpatient and emergency care will be provided by Spartanburg Regional and Mary Black Memorial Hospital, with the latter’s participation significant because the hospital was not viewed as a major safety net provider in Spartanburg County before this initiative. AccessHealth also has partnered with WelVista, a statewide nonprofit organization that assists uninsured patients with prescription medications donated by pharmaceutical companies.

To assess the success of the program, AccessHealth will monitor patient compliance, emergency department visits, hospital costs, patient satisfaction and provider satisfaction. Of an estimated 39,000 uninsured people potentially eligible for AccessHealth Spartanburg, the goal is to care for 1,000 people the first year. Although the program has broad community support, there is some concern about the capacity of the health care system in Spartanburg to handle what could eventually be many new patients.

Anticipating Health Reform

![]() hile the economic downturn was the foremost concern at the time of the site visit, respondents were beginning to consider national health reform’s potential impact while awaiting more details about the law. As in other markets, hospital respondents are concerned about how they will balance future declines in Medicaid DSH funding at the same time Medicaid coverage expands significantly without clarity about the level of Medicaid payment rates.

hile the economic downturn was the foremost concern at the time of the site visit, respondents were beginning to consider national health reform’s potential impact while awaiting more details about the law. As in other markets, hospital respondents are concerned about how they will balance future declines in Medicaid DSH funding at the same time Medicaid coverage expands significantly without clarity about the level of Medicaid payment rates.

Physician and hospital respondents generally are pessimistic about Medicare payment reductions under health reform. They are worried about maintaining profitability in the current fee-for-service environment while also moving toward the greater integration intended to shorten lengths of stay, reduce preventable hospital readmissions and create new organizational structures able to accept bundled payments. Given the high levels of physician-hospital alignment, hospitals and Regional HealthPlus considered themselves well positioned to become accountable care organizations (ACOs) that are responsible for the cost and quality of care for a defined patient population. At the same time, they recognize the challenge of developing the care processes and health information technology integration needed to function as ACOs. Health plans’ biggest concerns are preparing for the new state-based insurance exchange and meeting new medical-loss ratio requirements.

State officials expect that health reform will have a major impact. With the Medicaid expansions, the state expects to enroll an additional 400,000 people, resulting in Medicaid covering almost a third of the state’s population. Some safety net providers—especially the free clinics—were concerned that they would lose physician volunteers and financial support under the assumption that all of the uninsured would be covered, which most respondents believed is unlikely.

Issues to Track

Background Data

| Greenville Demographics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Greenville Metropolitan Area | Metropolitan Areas 400,000+ Population | |

| Population, 20091 | 926,439 | |

| Population Growth, 5-Year, 2004-20092 | 9.5% | 5.5% |

| Age3 | ||

| Under 18 | 23.7% | 24.8% |

| 18-64 | 63.4% | 63.3% |

| 65+ | 12.9% | 11.9% |

| Education3 | ||

| High School or Higher | 80.6% | 85.4% |

| Bachelor’s Degree or Higher | 25.1%# | 31.0% |

| Race/Ethnicity4 | ||

| White | 73.4% | 59.9% |

| Black | 17.9% | 13.3% |

| Latino | 5.7% | 18.6% |

| Asian | 1.7% | 5.7% |

| Other Races or Multiple Races | 1.3% | 4.2% |

| Other3 | ||

| Limited/No English | 4.3% | 10.8% |

# Indicates a 12-site low. |

||

| Economic Indicators | ||

|---|---|---|

| Greenville Metropolitan Area | Metropolitan Areas 400,000+ Population | |

| Individual Income less than 200% of Federal Poverty Level1 | 34.5% | 26.3% |

| Household Income more than $50,0001 | 45.7% | 56.1% |

| Recipients of Income Assistance and/or Food Stamps1 | 9.7% | 7.7% |

| Persons Without Health Insurance1 | 17.2% | 14.9% |

| Unemployment Rate, 20082 | 6.2% | 5.7% |

| Unemployment Rate, 20093 | 11.1%* | 9.2% |

| Unemployment Rate, July 20104 | 10.5% | 9.5% |

* Indicates a 12-site high. |

||

| Health Status1 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Greenville Metropolitan Area | Metropolitan Areas 400,000+ Population | |

| Chronic Conditions | ||

| Asthma | 16.8%* | 13.4% |

| Diabetes | 9.0% | 8.2% |

| Angina or Coronary Heart Disease |

6.1%* | 4.1% |

| Other | ||

| Overweight or Obese | 65.1% | 60.2% |

| Adult Smoker | 20.8% | 18.3% |

| Self-Reported Health Status Fair or Poor |

18.8%* | 14.1% |

* Indicates a 12-site high. |

||

| Health System Characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Greenville Metropolitan Area |

Metropolitan Areas 400,000+ Population | |

| Hospitals1 | ||

| Staffed Hospital Beds per 1,000 Population | 2.4 | 2.5 |

| Average Length of Hospital Stay (Days) | 5.5 | 5.3 |

| Health Professional Supply | ||

| Physicians per 100,000 Population2 | 199 | 233 |

| Primary Care Physicians per 100,000 Poplulation2 | 77 | 83 |

| Specialist Physicians per 100,000 Population2 | 121 | 150 |

| Dentists per 100,000 Population2 | 45# | 62 |

Average monthly per-capita reimbursement for beneficiaries enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare3 |

$661 | $713 |

# Indicates a 12-site low.. Sources:1 American Hospital Association, 2008 2 Area Resource File, 2008 (includes nonfederal, patient care physicians) 3 HSC analysis of 2008 county per capita Medicare fee-for-service expenditures, Part A and Part B aged and disabled, weighted by enrollment and demographic and risk factors. See www.cms.gov/MedicareAdvtgSpecRateStats/05_FFS_Data.asp. |

||

Community Reports are published by the Center for Studying

Health System Change:

600 Maryland Avenue, SW, Suite 550

Washington, DC 20024-2512

Tel: (202) 484-5261

Fax: (202) 484-9258

www.hschange.org

President: Paul B. Ginsburg