HSC Research Brief No. 21

November 2011

Aaron Katz, Laurie E. Felland, Ian Hill, Lucy B. Stark

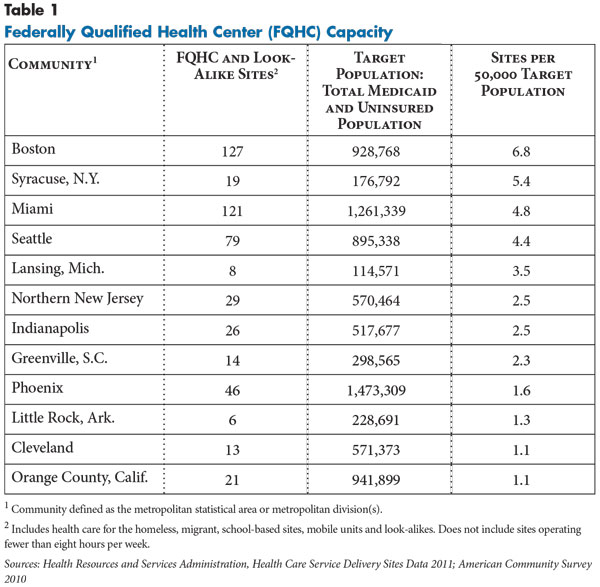

Community health centers have evolved from fringe providers to mainstays of many local health care systems. Those designated as federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), in particular, have largely established themselves as key providers of comprehensive, efficient, high-quality primary care services to low-income people, especially Medicaid and uninsured patients. The Center for Studying Health System Change’s (HSC’s) site visits to 12 nationally representative metropolitan communities since 1996 document substantial growth in FQHC capacity, based on growing numbers of Medicaid enrollees and uninsured people, increased federal support, and improved managerial acumen. At the same time, FQHC development has varied considerably across communities because of several important factors, including local health system characteristics and financial and political support at federal, state and local levels. Some communities—Boston; Syracuse, N.Y.; Miami; and Seattle—have relatively extensive FQHC capacity for their Medicaid and uninsured populations, while other communities—Lansing, Mich.; northern New Jersey; Indianapolis; and Greenville, S.C.—fall in the middle. FQHC growth in Phoenix; Little Rock, Ark.; Cleveland; and Orange County, Calif.; has lagged in comparison. Today, FQHCs seem poised to play a key role in federal health care reform, including coverage expansions and the emphasis on primary care and medical homes.

![]() racing their roots to the civil rights movement and the 1960s’ War on Poverty, federally qualified health centers play an important role in the U.S. health care system. Two physicians, Jack Geiger and Count Gibson of Tufts University, established the first health centers in South Boston and the Mississippi Delta to meet the large unmet needs of people in these poor communities by providing primary care regardless of patients’ ability to pay. By design, these centers were not just providers of medical care to individuals but also worked to improve the overall health of the community. Some hospitals and physicians fought the formation of community health centers, considering them antithetical to traditional medical practice—for example, some considered health centers socialized medicine.1

racing their roots to the civil rights movement and the 1960s’ War on Poverty, federally qualified health centers play an important role in the U.S. health care system. Two physicians, Jack Geiger and Count Gibson of Tufts University, established the first health centers in South Boston and the Mississippi Delta to meet the large unmet needs of people in these poor communities by providing primary care regardless of patients’ ability to pay. By design, these centers were not just providers of medical care to individuals but also worked to improve the overall health of the community. Some hospitals and physicians fought the formation of community health centers, considering them antithetical to traditional medical practice—for example, some considered health centers socialized medicine.1

Fast forward to March 2010—a major goal of the federal Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) of 2010 is to provide affordable coverage and primary care to more Americans. Many health reform provisions likely will enhance the role of FQHCs, while others may pose challenges to FQHCs by increasing competition for newly covered people, according to findings from HSC’s 2010 site visits to 12 nationally representative metropolitan communities (see Data Source).

Community health centers provide comprehensive preventive and primary care and other clinical services—for example, laboratory testing, radiology, pharmacy, dental care, behavioral health and even medical specialty care in some cases—and services that assist with access to care, such as language translation and transportation. FQHCs mainly serve low-income patients—incomes under 200 percent of federal poverty, or $44,700 for a family of four in 2011—who are uninsured or covered by Medicaid and other public programs. Many of these patients face challenges obtaining care from private physicians and other providers because of inability to pay or the low payment their insurance coverage provides. This patient base makes it difficult to generate sufficient revenue to expand services, add facilities or build infrastructure, such as electronic health records. But gaining FQHC designation—which provides cost-based Medicaid payments, grants to support capital and operational costs, discounted pharmaceuticals, access to National Health Service Corps clinicians, and medical malpractice liability protection—has allowed health centers to remain viable. Along with centers with full FQHC designation, a relatively small number of health centers has gained FQHC look-alike status, which provides most of the benefits that FQHCs receive but not the federal grants.

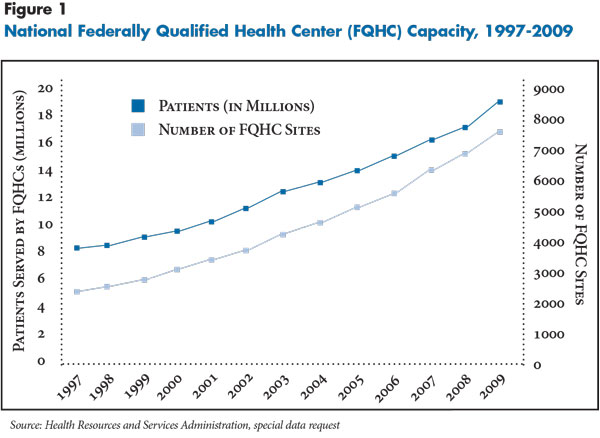

In the past 15 years, the demand for free or low-cost health care has grown, and FQHC capacity has expanded in response (see Figure 1). Since the mid-1990s, the ranks of uninsured Americans grew faster than the general population, while the willingness of private physicians to provide charity care declined.2 In addition, the proportion of the U.S. population covered by Medicaid increased from approximately 10 percent in 1999 to 17 percent in 2010.3 Federal support for FQHCs ramped up during the Bush administration (2001-08) and has continued under the Obama administration. Direct federal funding for FQHCs increased from roughly $750 million in 1996 to $2.2 billion in 2010, helping to increase the number of FQHC organizations nationally from about 700 to 1,200—with more than 8,100 sites of care. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 added another $2 billion in temporary FQHC funding for capital and service improvements through 2010.

However, the development and role of FQHCs has varied significantly across communities. In the last 15 years, the number of FQHC sites in the 12 communities studied increased to more than 500 by 2011 (see Table 1).4 The number of FQHC facilities ranges from more than 100 sites in Boston and Miami to just a handful of sites in Lansing and Little Rock. Taking into account the size of their uninsured and Medicaid populations, some communities now have extensive FQHC capacity—for example, Boston, Seattle, Syracuse and Miami—while others have lagged, including Phoenix, Little Rock, Cleveland and Orange County.

![]() wo key factors appear to affect development of FQHCs at the community level: the demand for safety net services and the level of state and local assistance.

wo key factors appear to affect development of FQHCs at the community level: the demand for safety net services and the level of state and local assistance.

Variation in demand: As a rough approximation of potential demand for FQHCs, the percentage of the population in 2010 that was either uninsured or had Medicaid coverage ranged from 23 percent in Boston to 51 percent in Miami. This range reflected state and local characteristics, such as differences in Medicaid-eligibility standards, employer offering of health insurance, availability of other subsidized or low-cost coverage, and demographics. For example, Boston is a relatively affluent community in a state where health reform has decreased an already-low uninsurance rate. In contrast, Miami’s large immigrant population and many small employers, which are less likely to provide coverage, contribute to the chronically high proportion of uninsured residents.

Also, health care market factors and general economic cycles affect changes in demand. For example, part of growing demand at the Syracuse FQHC was attributed to reduced provider capacity in an adjacent county. Although most FQHCs reported increased demand during the economic downturn, some FQHCs noted flat patient demand—for example, because of population loss in Cleveland and because immigrants reportedly left Phoenix in the face of Arizona’s increasingly inhospitable political and legal climate.

The federal criteria for attaining FQHC status, however, are more complex than documenting large numbers of uninsured people and Medicaid enrollees. Health centers must meet, or be poised to meet, a range of requirements (see box below). In addition, they must conduct a needs assessment and show that they serve a medically underserved area, known as a MUA, or that they treat a population that lacks access to available providers, known as a medically underserved population, or MUP. MUA criteria currently include the percentage of people with incomes below the federal poverty level, number of primary care providers available for the population, infant mortality rate, and percentage of the population aged 65 and older within a geographic area. A MUP designation involves applying the same criteria to a particular subpopulation that faces economic or cultural or linguistic barriers to care, such as low-income uninsured and Medicaid patients.5

However, these criteria alone do not appear to predict the degree of FQHC development in the 12 communities. For example, research shows physicians in northern New Jersey, Orange County and Phoenix were less willing to provide charity care or treat Medicaid patients in the mid-1990s, yet those communities had few FQHCs at the time.6 Among the 12 communities, Little Rock has a high poverty rate and a low supply of primary care physicians (PCPs) but has relatively few FQHCs.7

Some respondents perceived significant challenges in demonstrating need to start an FQHC or add sites. Orange County, for example, accessed Census data to determine and document demographic shifts among clinic neighborhoods throughout the county but still struggled in some cases to meet formal MUA definitions. Indeed, in some cases low-income neighborhoods are obscured within an overall higher-income area. A policy maker in Little Rock, which has the fewest FQHC sites of the 12 communities, noted that the presence of four large tertiary care hospitals—that serve the entire state—give the appearance of sufficient provider capacity, even though the community lacks outpatient providers to serve low-income people.

Variations in state and local assistance: In addition, the large range in FQHC capacity across communities suggests that some state and local environments are more conducive than others to establishing and expanding FQHCs. Assistance from the state and community helps a health center attain FQHC status. For instance, letters of support from elected officials and other community providers help demonstrate need for a new FQHC or additional sites. Health centers also need initial financial resources and capacity to meet the federal requirements. In the 12 communities, assistance to pursue FQHC status often has come from state primary care associations and community health center coalitions, as well as from state and local policy makers and agencies, health care providers and private foundations.

State and local support contributed to notable FQHC development in some communities. Boston’s local, state and federal elected officials have long been effective advocates, and an active state FQHC association provided ongoing strategic and technical assistance. FQHC development in Miami was aided by strategic planning assistance through the region’s FQHC coalition, Health Choice Network. Also, in 2002, Miami-Dade County voters approved a half-cent sales tax to support services for children, which helped to add more than 80 school-based FQHC sites.

The communities of northern New Jersey and Orange County made particular strides in establishing FQHCs in recent years. In the early 2000s, New Jersey policy makers allocated general funds to FQHCs that, along with leadership from the state’s primary care association, helped significantly increase the number of FQHC sites across the state. FQHCs in northern New Jersey grew from one organization with six sites in 1996 to approximately five organizations operating almost 30 sites by 2011. Safety net respondents in Orange County indicated that greater local investment in the federal application process was prompted by several factors, including enhanced leadership and collaboration in the local health center consortium, clinic physicians and managers who worked in FQHCs elsewhere moving to Orange County, and a 2006 visit by then-President Bush who questioned business leaders why the community was not taking advantage of the FQHC program. The county then provided staff and other resources to help with the application process, and FQHCs in Orange County increased from a single organization to five.

Some communities appear to lack the impetus or resources to expand FQHC capacity. Little Rock respondents lamented insufficient local support to pursue a federal expansion grant. As one respondent said, “At some point, things have to get bad enough that the political will is raised high enough to make change happen.” In some cases, communities or specific clinics may not want federal support. As one community observer noted, “The free clinics are embraced more by the community at large…providing the charity out of the goodness of their heart.” In Little Rock, Greenville and Lansing, some church-funded clinics preferred to remain volunteer based and to not offer some federally mandated services. Also, some clinics want to maintain their focus on the uninsured and/or not take on the administrative burdens associated with federal status and billing insurers or meeting other federal requirements, such as charging patient fees and naming consumers to serve as a majority of governing board members.

In addition to or in lieu of helping health centers to gain federal status, some local and state governments provided ongoing funding to help existing health centers care for the uninsured. For example, state tobacco taxes helped a Little Rock FQHC weather financial problems. Cleveland, Miami and Seattle set aside local tax revenue to support health centers, and in Orange County, Indianapolis and Lansing, community programs to manage care for uninsured people reimburse health centers—and other providers—for treating enrollees. In some cases, however, these funds declined recently because of budget constraints. For example, Arizona, California and Ohio eliminated tobacco-tax-based funding to health centers.

Summary of Federally Qualified Health Center Requirements

|

![]() ey to FQHCs gaining and maintaining federal and other support has been demonstrating effective use of resources and becoming more self-sufficient. Many FQHCs began as grassroots, shoestring operations, often managed by community activists or clinicians. Over time, many FQHC directors have become sophisticated leaders and managers.8 Further, many FQHCs have built reputations as high-quality, efficient providers. This is consistent with research showing, for example, that health center patients’ conditions are better managed and that they incur lower total medical expenditures than patients using other providers.9

ey to FQHCs gaining and maintaining federal and other support has been demonstrating effective use of resources and becoming more self-sufficient. Many FQHCs began as grassroots, shoestring operations, often managed by community activists or clinicians. Over time, many FQHC directors have become sophisticated leaders and managers.8 Further, many FQHCs have built reputations as high-quality, efficient providers. This is consistent with research showing, for example, that health center patients’ conditions are better managed and that they incur lower total medical expenditures than patients using other providers.9

FQHC leaders have focused on related strategies to strengthen their centers’ financial status and sustainability. In many cases, they increased the proportion of insured patients, adapted to Medicaid managed care, collected payments due from payers and patients, and increased operational efficiencies. Still, FQHC leaders faced significant challenges, including operating costs that rose faster than revenues, difficulties meeting demand and arranging for all services their patients need—particularly specialty care—and complex and changing payer requirements.

Pursuing insured patients. As both operational costs and uninsured rates rose, FQHCs focused considerable attention on increasing their percentage of insured patients to bring in revenue. FQHCs mainly worked to increase Medicaid patients, both because this population fits squarely within their mission and because Medicaid is typically their best payer. They also increased staff capacity to help uninsured patients apply for public coverage and, in some cases, increased outreach to attract privately insured people.

Medicaid per-visit payment rates to FQHCs and look-alikes typically are significantly more than private physician payment rates to account for the broader array of clinical and other services FQHCs provide. Prior to this decade, Medicaid programs reimbursed FQHCs in a manner that closely approximated their actual costs, but in 2001, federal legislation required FQHCs to move to a prospective payment system (PPS). The PPS is based on health centers’ previous average costs, updated annually for medical inflation. Some states provide extra payment to FQHCs.

Many FQHCs have boosted the number of Medicaid patients they treat. Nationally, by 2010, Medicaid patients made up 39 percent of FQHC patients, up from 31 percent in 1996—with uninsured patients remaining at about 40 percent and the remainder a mix of Medicare and privately insured patients.10 A Phoenix FQHC even reversed its previous 55 percent uninsured/30 percent Medicaid mix of patients over a four-year period, significantly alleviating financial stress.

FQHCs used a number of strategies to attract more insured patients, including general marketing of the FQHC and emphasizing quality of care. For instance, ads by a Miami FQHC point out both its range of services and accreditation by the Joint Commission—attained by nearly a third of FQHCs nationally.11 A few FQHCs also expanded services in demand by insured patients. For example, an FQHC in Cleveland recognized a shortage of dentists in the area for the general population and opened a separate dental facility to attract privately insured or self-pay patients, using earnings to help subsidize dental care for Medicaid and low-income, uninsured patients. Also, many FQHCs upgraded facilities to both attract new patients and retain existing ones. As an Orange County respondent said, “[Attracting patients is] a major reason why a lot of our clinics have undergone huge renovations—going toward being a provider of choice, rather than provider of last resort.”

Shaping Medicaid managed care. Concerned they might lose Medicaid patients to other providers as states adopted managed care arrangements in the 1990s, FQHCs worked with state Medicaid programs and positioned themselves to be part of health plans’ primary care networks. States are required to reimburse FQHCs the difference between what health plans pay and the FQHC cost-based rate, in what are commonly called “wraparound payments.” Nationally, more than half of FQHCs’ Medicaid patients were in managed care arrangements by 2009.12

In four of the 12 communities—Seattle, Syracuse, Boston and Miami—FQHCs as a group operate health plans. These plans tend to have among the highest Medicaid enrollments in their markets, in part because of state decisions that favor these plans in assignment of enrollees who do not choose a specific plan or provider. And health centers, themselves, receive revenues from the efficient operation of these plans.

FQHCs in the other eight communities typically contract with all or many of the Medicaid health plans in their markets and, in some cases, have worked with the state Medicaid agency to gain health plan enrollees as patients. In Orange County, for example, a recent change in how the county Medicaid plan assigns enrollees to a provider if they do not choose one favors FQHCs.

Improving billing and collection practices. In the last 15 years, FQHCs have increased attention to billing third-party payers and collecting patient fees necessary to meet federal requirements. Some health centers invested in information technology to improve the timeliness and accuracy of billing and collections. Others achieved similar gains by outsourcing or collaborating. For example, Miami FQHCs achieve economies of scale by having their FQHC coalition lead these functions.

Because asking poor patients for even a few dollars was anathema for many health center employees, this change often required a cultural shift. For example, the chief executive officer of a Phoenix FQHC cited the challenge of convincing staff that collecting patient fees is critical to the center’s financial viability. Although FQHC directors said they still treat patients regardless of ability to pay, the fees may be a barrier for patients. Some Miami safety net respondents believed that patient cost-sharing requirements suppressed demand at FQHCs during the recession.

Given FQHCs’ dependence on Medicaid revenues and grant funds, their growth generated some competitive tensions among FQHCs and other providers. Leaders of some free clinics and other providers that do not expect payment reported that FQHCs’ focus on Medicaid patients and payment collection led more uninsured patients to their facilities. In some communities, FQHCs cited concerns about other providers, including hospital clinics, seeking FQHC status or expanding into existing FQHC service areas.

Improving operational efficiencies. FQHCs also focused on operating more efficiently. Given the challenges their patients face in keeping appointments—because of such barriers as inadequate transportation or inability to get time off of work—FQHCs increased flexibility in how patients can seek care. Many allowed patients to be seen on a walk-in basis or to schedule same-day appointments. Both strategies improve efficiency by reducing missed appointments and the need to reschedule them.

Improving productivity was another focus. Many health centers provide care through teams of various types of clinicians and other staff to serve more patients. Also, an FQHC in northern New Jersey, for example, began offering incentives to providers whose productivity increased. Improving physical plants also was a key strategy. Some FQHCs started in buildings that were relatively inexpensive to lease but not designed for medical services, and they have remodeled or built new facilities to use administrative and clinical space more efficiently.

![]() stimated to expand coverage to 32 million people by 2019, PPACA seeks to make health care more available and affordable. Respondents pointed to three areas where FQHCs appear poised to assume a significant role under health reform: coverage expansions, primary care workforce development, and new models of health care delivery and payment.

stimated to expand coverage to 32 million people by 2019, PPACA seeks to make health care more available and affordable. Respondents pointed to three areas where FQHCs appear poised to assume a significant role under health reform: coverage expansions, primary care workforce development, and new models of health care delivery and payment.

Coverage expansions. Under the law, Medicaid eligibility in 2014 will expand to include all people with incomes up to 138 percent of federal poverty ($30,843 for a family of four in 2011) and subsidized private coverage will become available to people with incomes up to 400 percent of poverty ($89,400 for a family of four in 2011). As a result, FQHCs hope to both retain their previously uninsured patients who gain coverage, as well as attract additional insured patients. To the extent this happens, additional revenues will enhance FQHCs’ financial stability.

In fact, the law requires private plans offering products in insurance exchanges to have sufficient numbers of essential community providers, including FQHCs, in their networks. However, the level of payment FQHCs will receive from exchange plans appears uncertain: while one part of the law states that plans must pay FQHCs at least their cost-based Medicaid payment rates, another part states that plans can decline to contract with essential community providers that do not accept the plan’s rates. Boston’s experience under state health reform enacted in 2006— where FQHCs today are major providers of care for both people newly covered by Medicaid and those with subsidized private insurance—may portend an expanded role for FQHCs in other communities.

To help meet the increased demand, PPACA also permanently reauthorized the FQHC program and appropriated an extra $11 billion in grant funding to double FQHC capacity to treat approximately 20 million more insured and uninsured people by 2015. Health centers in all but one—Syracuse—of the 12 communities already have received more than $50 million of these funds. Little Rock and Greenville, however, have received less than $100,000 total to date, just a fraction of what others have received, particularly Boston, Seattle, Cleveland and Phoenix. This suggests that the communities with an already extensive FQHC infrastructure may be better positioned to receive additional grants for expansions.

The law also mandated the formation of a federal committee to revise the method for assessing underserved areas (including MUA and MUP designations); the interim final rule has not yet been published.13

Primary care workforce. The coming coverage expansions have raised concerns about having enough primary care clinicians to serve newly covered people. FQHCs have experience in building such capacity—especially though their primary care teams of physicians and midlevel providers, such as nurse practitioners—and PPACA provisions likely will support their continued role.

Although FQHCs face periodic difficulties in hiring clinical staff because clinicians can earn more in other settings, directors typically said they have been able to recruit and retain enough primary care providers through the National Health Service Corps (NHSC), which helps repay student loans and provides scholarships for clinicians who commit to work in underserved areas. FQHCs also are attractive to other physicians who are interested in the safety net mission, predictable working hours and salary, and malpractice liability protection. The health reform law provides an additional $1.5 billion to expand the NHSC by an estimated 15,000 providers by 2015. In addition, PPACA supports the role FQHCs play as training sites for medical and dental students—which also expands FQHCs’ capacity to see more patients—by authorizing $230 million between fiscal years 2011 and 2015 to support health-center-based residency programs.

New care and payment models. FQHCs also appear well suited to the delivery system changes envisioned by reform. The law establishes medical-home pilots designed to coordinate patient care across providers and settings. FQHCs have significant experience in helping to coordinate care with specialists and other providers out of necessity, because their patients otherwise face significant barriers to care.

Further, final federal rules on Medicare accountable care organizations (ACOs) authorize FQHCs to participate in or form their own ACOs. Although FQHCs typically treat a relatively small percentage of Medicare patients, this may change if other primary care capacity tightens, as FQHCs’ baby-boomer patients “age into” Medicare and as Medicare payment rates to FQHCs are expected to increase in 2014 under a new methodology.14 Thirty-one of the 500 FQHC sites in the 12 communities have been selected for a Medicare Advanced Primary Care Practice demonstration project, in which the health centers will receive monthly payments to create care management plans for their Medicare patients.

In some communities, FQHCs are already collaborating with others to develop new care and payment models. For example, FQHCs in Seattle joined the Washington Patient-Centered Medical Home Collaborative, and FQHCs are a key part of the “managed system of care” model underway in Orange County, which aims to transition uninsured people into new coverage options.

![]() till, some respondents pointed to potential problems for FQHCs. In April 2011, a budget compromise between the administration and Congress cut $600 million from fiscal year 2011 discretionary FQHC funding. This cut has significantly reduced the number of federal grants for new sites and curtailed new expansion grants and could be a harbinger for further cuts as the administration and Congress focus on federal-deficit reduction.15

till, some respondents pointed to potential problems for FQHCs. In April 2011, a budget compromise between the administration and Congress cut $600 million from fiscal year 2011 discretionary FQHC funding. This cut has significantly reduced the number of federal grants for new sites and curtailed new expansion grants and could be a harbinger for further cuts as the administration and Congress focus on federal-deficit reduction.15

FQHC leaders are especially nervous about whether funding will be sufficient to care for people who remain uninsured. The law’s coverage expansions exclude undocumented immigrants, who are expected to make up about one-third of the more than 20 million people expected to remain uninsured. Some worried that public and private funding that FQHCs receive could become a political target for cuts if it is perceived that such funding is supporting care for undocumented immigrants. This fear was especially pronounced in communities with larger immigrant populations, such as Orange County, northern New Jersey and Miami.

Further, FQHC leaders have some concern about possible increased competition with private health care providers. As coverage expansions turn many charity patients into paying patients, private physicians and hospitals may compete more for these traditional FQHC patients. Although this concern largely has not played out in the past, and did not occur in Boston after Massachusetts enacted health reform, PPACA increases Medicaid primary care payment rates to Medicare rates in 2013 and 2014, making these patients somewhat more attractive. As a Little Rock respondent said, “Our [FQHC] has to be just as competitive as a private physician’s office, and our service has to be at that level.”

![]() ederal policy makers from both political parties appear to envision FQHCs as key to expanding access to care for low-income people. FQHCs’ ability to provide coordinated, comprehensive primary care and support services in an efficient manner is particularly important to people with complex medical and social needs. Additionally, FQHC strategies for helping uninsured people enroll in public insurance could be helpful to state outreach efforts, and their experience in providing culturally competent care and coordinating multi-disciplinary services could be useful to private medical groups.

ederal policy makers from both political parties appear to envision FQHCs as key to expanding access to care for low-income people. FQHCs’ ability to provide coordinated, comprehensive primary care and support services in an efficient manner is particularly important to people with complex medical and social needs. Additionally, FQHC strategies for helping uninsured people enroll in public insurance could be helpful to state outreach efforts, and their experience in providing culturally competent care and coordinating multi-disciplinary services could be useful to private medical groups.

As more people gain coverage under federal health reform, establishing sufficient primary care capacity to meet the additional demand will be a challenge. The significant variation in federal support for FQHCs across communities, as well as state and local factors that affect both FQHC and broader safety net capacity, likely will affect communities’ ability to meet increased demand for primary care services. Communities with a relatively large proportion of their residents currently uninsured—including Miami, Orange County, Greenville and Phoenix—may experience a particular surge in demand for primary care as many residents gain insurance. Further, the pervasiveness of budget challenges and the sluggish economy could endanger existing state and local support for safety net providers. States may have ongoing—even growing—difficulties in supporting FQHCs’ Medicaid payment rates and other funding for safety net providers.

Though PPACA makes explicit provisions for FQHCs, how reform affects the composition of the traditional safety net and the broader primary care delivery system—and with what impact on access to and coordination of care—remains to be seen. Some outstanding questions include the extent to which FQHCs will become primary providers for other populations, such as those covered by subsidized private coverage and Medicare; whether other providers will serve more Medicaid patients; and how providers solely serving the remaining uninsured will fare.

| 1. | Lefkowitz, Bonnie, Community Health Centers: A Movement and the People Who Made It Happen, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, N.J. (2007). |

| 2. | Cunningham, Peter J., and Jessica H. May, A Growing Hole in the Safety Net: Physician Charity Care Declines Again, Tracking Report No. 13, Center for Studying Health System Change, Washington D.C. (March 2006). |

| 3. | DeNavas-Walt, Carmen, Bernadette D. Proctor and Jessica C. Smith, Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2009, U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, D.C. (September 2010); U.S. Census Bureau, 2010 American Community Survey, Washington, D.C. (2010). Available at http://factfinder2.census.gov/. |

| 4. | Unable to get exact count of sites for 1996 because Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) changed its methodology between these two periods. |

| 5. | HRSA, Medically Underserved Areas & Populations (MUA/Ps), Rockville, Md. (Revised June 1995). Available at http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/shortage/muaps/index.html. |

| 6. | Unpublished estimates from the Community Tracking Study Physician Survey, 1996-97. |

| 7. | U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, Washington, D.C. (2008). Available at http://factfinder.census.gov/. And Bureau of Health Professions, Area Resource File, HRSA, Rockville, Md. (2008). |

| 8. | Felland, Laurie E., J. Kyle Kinner and John F. Hoadley, The Health Care Safety Net: Money Matters But Savvy Leadership Counts, Issue Brief No. 66, Center for Studying Health System Change, Washington, D.C. (August 2003). |

| 9. | Falik, Marilyn, et al., “Comparative Effectiveness of Health Centers as Regular Source of Care: Application of Sentinel ACSC Events as Performance Measures,” Journal of Ambulatory Care Management, Vol. 29, No. 1 (January-March 2006); and Ku, Leighton, et al., Using Primary Care to Bend the Curve: Estimating the Impact of a Health Center Expansion on Health Care Costs, Policy Research Brief No. 14, The George Washington University School of Public Health and Health Services, Geiger Gibson/RCHN Community Health Foundation Research Collaborative, Washington, D.C. (September 2009). |

| 10. | National Association of Community Health Centers, United States Health Center Fact Sheet, Bethesda, Md. (2009). Available at http://www.nachc.com/client/US10.pdf. |

| 11. | The Joint Commission, Joint Commission Accredited Health Centers by State and HRSA Regional Divisions, Oakbrook Terrace, Ill. (2011). Available at http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/PenetrationRatios_as_of_070111_UDS.xls. |

| 12. | National Association of Community Health Centers, A Sketch of Community Health Centers: Chart Book 2009, Bethesda, Md. (2009). Available at http://www.nachc.com/client/documents/Chartbook%20FINAL%202009.pdf. |

| 13. | Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Public Law No. 111-148, Sec. 5602. |

| 14. | Medicare Payment Advisory Committee, Report to the Congress: Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System, Chapter Six, Washington, D.C. (June 2011). |

| 15. | Rosenbaum, Sara, and Peter Shin, Community Health Centers and the Economy: Assessing Centers’ Role in Immediate Job Creation Efforts, Policy Research Brief No. 25, The George Washington University School of Public Health and Health Services, Geiger Gibson/RCHN Community Health Foundation Research Collaborative, Washington, D.C. (September 2011). |

Since 1996, HSC has conducted site visits to 12 nationally representative metropolitan communities every two to three years as part of the Community Tracking Study (CTS) to interview health care leaders about the local health care market and how it has changed. The communities are Boston; Cleveland; Greenville, S.C.; Indianapolis; Lansing, Mich.; Little Rock, Ark.; Miami; northern New Jersey; Orange County, Calif.; Phoenix; Seattle; and Syracuse, N.Y. During the seventh round of site visits, almost 550 interviews were conducted in the 12 communities between March and October 2010. This Research Brief primarily draws from interviews with directors of FQHCs and other health centers, as well as community health center associations; 55 such organizations were interviewed in the 2010 site visits. In addition, researchers reviewed research syntheses and published reports from CTS’s six previous rounds of site visits.

The 2010 Community Tracking Study site visits and resulting publications were funded jointly by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the National Institute for Health Care Reform.

RESEARCH BRIEFS are published by the Center for Studying Health System

Change.

600 Maryland Avenue, SW, Suite 550

Washington, DC 20024-2512

Tel: (202) 484-5261

Fax: (202) 484-9258

www.hschange.org