HSC Research Brief No. 22

April 2012

Ha T. Tu, Divya R. Samuel

Spending on specialty drugs—typically high-cost biologic medications to treat complex medical conditions—is growing at a high rate and represents an increasing share of U.S. pharmaceutical spending and overall health spending. Absence of generic substitutes, or even brand-name therapeutic equivalents in many cases, gives drug manufacturers near-monopoly pricing power and makes conventional tools of benefit design and utilization management less effective, according to a new qualitative study from the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC). Despite the dearth of substitutes, cost pressures have prompted some employers to increase patient cost sharing for specialty drugs. Some believe this is counter-productive, since it can expose patients to large financial obligations and may reduce patient adherence, which in turn may lead to higher costs. Utilization management has focused on prior authorization and quantity limits, rather than step-therapy approaches—where lower-cost options must first be tried—that are prevalent with conventional drugs. Unlike conventional drugs, a substantial share of specialty drugs—typically clinician-administered drugs—are covered under the medical benefit rather than the pharmacy benefit. The challenges of such coverage—high drug markups by physicians, less utilization data, less control for health plans and employers—have led to attempts to integrate medical and pharmacy benefits, but such efforts are still in early development. Health plans are experimenting with a range of innovations to control spending, but the most meaningful, wide-ranging innovations may not be feasible until substitutes, such as biosimilars, become widely available, which for many specialty drugs will not occur for many years.

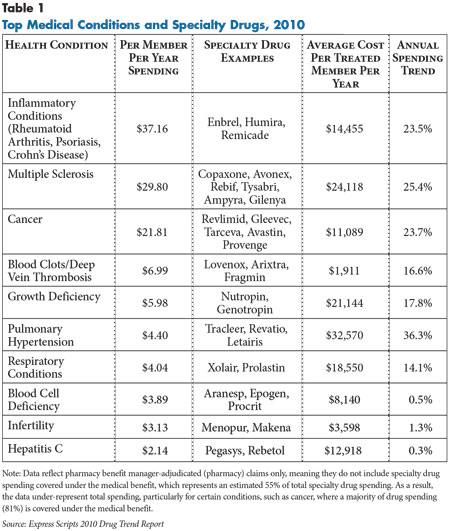

![]() pecialty drugs—typically high-cost biologic medications used to treat a variety of serious, complex conditions ranging from cancer to rheumatoid arthritis to blood disorders—are an increasing concern for employers and other purchasers (see Table 1). While specialty drugs are prescribed for only one in every 100 commercial health plan enrollees, these drugs account for an estimated 12 percent to 16 percent of commercial prescription drug spending today.1 Spending on specialty drugs is expected to rise dramatically as drugs currently in development come to market during the next decade and beyond.

pecialty drugs—typically high-cost biologic medications used to treat a variety of serious, complex conditions ranging from cancer to rheumatoid arthritis to blood disorders—are an increasing concern for employers and other purchasers (see Table 1). While specialty drugs are prescribed for only one in every 100 commercial health plan enrollees, these drugs account for an estimated 12 percent to 16 percent of commercial prescription drug spending today.1 Spending on specialty drugs is expected to rise dramatically as drugs currently in development come to market during the next decade and beyond.

Decisions about specialty drug coverage involve difficult trade-offs for payers and purchasers, according to interviews with representatives from health plans, benefits consulting firms, pharmacy consulting firms and other industry experts (see Data Source). The challenge inherent in weighing extremely high costs for individual patients against specialty drugs’ ability, in many cases, to extend lives and change the course of diseases rather than just treat symptoms is profound.

Unlike conventional drugs, where spending trends have moderated for a variety of reasons, including patent expirations, generic substitution and patient incentives to use preferred brand-name drugs, specialty drugs have persistently high trends, ranging from 14 percent to 20 percent annually in recent years for the three largest pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs).2 While increased utilization and price increases both drive specialty drug spending, the latter typically plays a larger role.3 This reflects the inability of payers to exert downward pressure on price, given the market power of single-source drug manufacturers.

No standard definition exists for specialty drugs. Health plans and PBMs, which often use or own specialty pharmacies, employ their own criteria, definitions and drug lists (see box below). Most specialty drugs are biologic—derived from living organisms—in contrast to the vast majority of conventional drugs made from chemical compounds.5 While specialty drugs are typically administered by injection or infusion, they now also include oral and inhaled drugs. In fact, new-generation oral drugs to treat cancer and multiple sclerosis, among other conditions, often cost far more than their injectable and infusible counterparts. Some of the defining characteristics of specialty drugs include:

Specialty drugs do not fit as neatly as conventional drugs into traditional benefit structures. While self-administered specialty drugs are almost always covered under the pharmacy benefit, specialty drugs administered by physicians or others in clinical settings—known as office-administered agents—typically have been covered under the medical benefit. Spending under the medical benefit is estimated to account for 55 percent of total commercial spending on specialty drugs.7 The division of benefit structures makes management of specialty drugs more complex and challenging for payers.

This Research Brief examines three major approaches to specialty drug management—benefit design, pricing, and utilization and care management. While some innovations in management hold promise, each approach has key limitations, largely because the current dearth of substitutes—both generic and brand name—leads to pricing power of single-source manufacturers and reduces the applicability of a range of key tools commonly used to control spending on conventional drugs.

Health Plans, PBMs and Specialty PharmaciesSpecialty pharmacy providers are companies involved in overseeing the distribution, management and reimbursement of specialty drugs. The specialty pharmacy industry grew out of several different market sectors but is dominated today by the PBM industry.4 The standalone PBMs—those unaffiliated with health plans, including giants Express Scripts, CVS/Caremark and Medco—have either purchased existing specialty pharmacies or built in-house capability. For fully insured products, where health plans have full latitude in determining specialty drug strategies, plans’ approaches toward outsourcing depend primarily on plan size and in-house capabilities. Some large national plans have their own specialty pharmacy divisions, while regional and local plans tend to contract with one or more specialty pharmacies—most often those owned by large standalone PBMs—to negotiate prices and perform distribution and handling functions. However, utilization management is a function that plans typically keep in-house, as PBMs are seen as having little incentive to keep utilization in check. For self-insured products, where employers can determine whether to carve out pharmacy benefits from medical benefits, employers nearly always use the same vendor for specialty drugs that they use for conventional drugs. That is, if conventional drug management is carved out to a separate PBM, specialty drug management is almost always included in that same carve-out; if the medical carrier (health plan) is responsible for pharmacy management, that carrier has oversight over both conventional and specialty drugs. |

![]() ormulary exclusions. Mainstream commercial insurance products rarely exclude specialty drugs from their formularies. Once a new specialty drug receives approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the health plan’s pharmacy and therapeutics (P&T) committee, its addition to the formulary is typically assured. P&T committee review typically focuses on ensuring safe and appropriate use and preventing off-label use, rather than restricting access to specialty drugs. The rare exceptions to this pattern of comprehensive formulary inclusion are found in the few specialty drug classes where many close substitutes exist—for example, growth hormone—and some niche insurance products aimed at individual and small-group purchasers that provide limited benefits to achieve much lower premiums.

ormulary exclusions. Mainstream commercial insurance products rarely exclude specialty drugs from their formularies. Once a new specialty drug receives approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the health plan’s pharmacy and therapeutics (P&T) committee, its addition to the formulary is typically assured. P&T committee review typically focuses on ensuring safe and appropriate use and preventing off-label use, rather than restricting access to specialty drugs. The rare exceptions to this pattern of comprehensive formulary inclusion are found in the few specialty drug classes where many close substitutes exist—for example, growth hormone—and some niche insurance products aimed at individual and small-group purchasers that provide limited benefits to achieve much lower premiums.

Four-tier pharmacy benefit design. For specialty drugs covered under the pharmacy benefit, some employers choose to transfer a portion of the high costs to patients by adding another, higher cost-sharing tier to the standard three-tier pharmacy benefit design. While it is hard to generalize about the multitude of four-tier designs, the practice of transitioning from flat-dollar copayments in the lowest three tiers to coinsurance, where the patient pays a percentage of the total drug cost, in the fourth tier is quite common. A typical design might require a generic copayment of $15, a preferred brand copayment of $30, a nonpreferred-brand copayment of $60, and specialty drug coinsurance in the range of 10 percent to 25 percent. Within the fourth tier, some employers—especially large employers—retain a degree of financial protection for patients by applying out-of-pocket maximums per prescription fill—for example, $100 to $250—or per year—perhaps, $5,000.

Tier placement of specialty drugs varies greatly across plans. Under some three-tier and four-tier designs, all specialty drugs are placed in the highest cost-sharing tier. However, other designs are more nuanced: Where substitutes exist, preferred specialty drugs might be in a lower tier. Rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis and growth deficiency are some of the conditions for which preferred specialty drugs have become increasingly available. In some cases, drugs achieve preferred status by being deemed therapeutically superior; in other cases, by being judged more cost-effective. In the latter category, there is often a negotiation between a manufacturer and a health plan or PBM, with drug discounts or rebates granted in exchange for preferred tier placement.

The prevalence of a fourth tier varies dramatically across health care markets. Four-tier designs are much less prevalent in markets characterized by historically rich benefits. For example, in Lansing and other Michigan communities with strong union presence, large employers’ pharmacy benefits are still transitioning from two-tier to three-tier designs. State policy also can play a key role in limiting four-tier penetration: In 2010, New York became the first state to pass legislation prohibiting four-tier pharmacy benefit designs in fully insured products. In addition, four-tier penetration varies greatly by market segment: The smaller an employer, the greater the price-consciousness and likelihood of adopting a four-tier design. Finally, differences among health plan and employer philosophies and strategies are key in four-tier adoption. Aetna and WellPoint are among the national health plans more actively offering four-tier designs; about half of their small-to-mid-sized group members were covered by such designs as of 2011. In contrast, Cigna—citing concerns about affordability and patient adherence—does not offer four-tier pharmacy benefits in its fully insured product line, though it does accommodate requests from self-insured employers for four-tier designs.

Using patient cost-sharing incentives to affect drug choice—an effective approach to moderating conventional drug spending trends—works best for the few specialty drug classes where close substitutes do exist. The example experts often cite is growth hormones, where “you have six options and basically have great similarity between agents, so [that lends itself] to benefit design differentiation,” according to a specialty pharmacy director for a national health plan. For most specialty drugs, however, close substitutes either do not exist or are few. In such cases, higher cost sharing tends to transfer financial burden to patients without an opportunity to change their behavior in cost-effective ways.

Several respondents took issue with markedly increasing patient cost sharing on philosophical grounds, noting that the medical conditions being treated by most specialty drugs are typically rare, complex, expensive and beyond the control of patients—the very situations for which insurance is intended to provide financial protection. “These are not lifestyle drugs. [Employers with four-tier designs] are almost punishing patients for having a disease state,” one pharmacy consultant observed.

Some experts also took issue with four-tier benefit designs on practical grounds, arguing that higher cost sharing can be counterproductive by leading patients to stop adhering to drug regimens, which can in turn lead to complications requiring hospitalizations and other costly interventions. Views were mixed as to whether employers end up paying more or less in direct medical costs under benefit designs requiring higher out-of-pocket costs for specialty drugs. That cost-benefit calculation is complex and dependent on such factors as employee turnover and the prevalence of health conditions in a particular employee/dependent population. Several experts cited the example of hepatitis C. There is strong evidence, they argued, that high out-of-pocket costs—along with strong drug side effects—can lead patients to abandon effective specialty drugs—including a new generation of drugs that better target the hepatitis C virus and can increase the cure rate from 40 percent to almost 80 percent for the most common virus strain. Left untreated, hepatitis C ultimately can result in such grave outcomes as liver failure. However, because these outcomes take many years to develop, it is uncertain whether the employer now paying for health benefits will be the same purchaser bearing the consequences down the line.

Experts noted that adoption of four-tier pharmacy designs was not necessarily an unalterable decision for employers. One benefits consultant said, “A few years ago, we had tons of clients who did a fourth tier, and some rescinded it. Some went too high, and they backed down.” Such reversals reportedly reflect not only smaller savings in direct medical costs than expected in some cases, but also rethinking by some employers of the equity of high out-of-pocket cost exposure for very sick employees.

Innovations. Some experts advocated the extension of value-based benefit design (VBBD) to include specialty drugs. Under this approach—the opposite of adding a fourth tier—patient cost barriers are reduced or eliminated to encourage adherence with treatments regarded as high value. Over the past decade, many large employers have used VBBD to reduce cost sharing for conventional drugs used to treat diabetes, hypertension and other common chronic conditions. While some large employers have shown interest in extending VBBD to specialty drugs, the high upfront costs reportedly have made them reluctant to implement this approach. “They are taking a wait-and-see approach. waiting for [another employer] to be the pioneer and demonstrate that it works. that it will save money,” one expert observed. Two conditions mentioned as affecting productivity of working-age people are multiple sclerosis and hepatitis C, so drugs controlling these conditions are considered prime candidates for VBBD.

Another approach, income-based benefit design, is designed to vary cost-sharing levels according to patients’ earnings. As one expert said, this approach “spreads the pain in a more equitable. [and] sustainable way.” This strategy has been implemented by a relatively small number of innovative employers. One engineering firm, for example, has high average earnings, but support and junior staff earn substantially less. This firm implemented three tiers of income-based cost sharing on top of its three-tiered pharmacy benefit design, requiring highly paid employees to pay a higher share out of pocket.

Another innovation—the integration of medical and pharmacy benefits—has garnered strong interest (see box below for more about integrating medical and pharmacy benefits). In terms of benefit design, this approach seeks to equalize patient cost sharing between the medical and pharmacy benefits, so that patients don’t have distorted incentives to use one over the other.

Integration of Medical and Pharmacy BenefitsCurrently, specialty drugs can fall under either the medical, pharmacy benefit or both benefits. This division can occur within a therapy class as in the case of TNF inhibitors to treat rheumatoid arthritis: Remicade, an office-administered agent, typically is covered under the medical benefit, while self-administered agents Enbrel and Humira are covered under the pharmacy benefit. An example of a single drug falling under both the medical and pharmacy benefit is a drug that initially requires administration in a physician’s office, but can then be self-administered once the patient has been taught the technique. This fragmented benefit structure can mean different patient cost sharing, provider reimbursement, utilization management rules, clinical care management approaches and claims data reporting, in turn leading to misaligned incentives for patients and providers and lack of coordination in managing patients, among other issues. As a result, many payers are attempting to integrate specialty drugs under one benefit. In some cases, integration efforts focus on moving drugs under the medical benefit to the pharmacy benefit. Increasingly, however, efforts are focused on moving all specialty drugs into a separate specialty drug benefit, with the following ultimate goals, no matter where the drug is dispensed or administered:

|

![]() btaining lowest unit price. For specialty drugs covered under the pharmacy benefit, health plans take different approaches to obtain discounted prices from specialty drug manufacturers. It is common for smaller health plans to turn to one of the major PBMs—which all have acquired or developed their own specialty pharmacy divisions—to negotiate unit prices on their behalf, since the largest PBMs are best able to leverage their high volumes to obtain the steepest discounts from manufacturers. Health plans with high volumes overall—such as the major national plans—or large regional market shares—such as some Blue Cross Blue Shield plans—often find it more advantageous to negotiate prices with manufacturers directly rather than relying on a PBM. Whatever their approach to price negotiations, when it comes to the distribution of specialty drugs to patients, most health plans contract with specialty pharmacies, since these entities have expertise on such matters as special drug handling and patient education.

btaining lowest unit price. For specialty drugs covered under the pharmacy benefit, health plans take different approaches to obtain discounted prices from specialty drug manufacturers. It is common for smaller health plans to turn to one of the major PBMs—which all have acquired or developed their own specialty pharmacy divisions—to negotiate unit prices on their behalf, since the largest PBMs are best able to leverage their high volumes to obtain the steepest discounts from manufacturers. Health plans with high volumes overall—such as the major national plans—or large regional market shares—such as some Blue Cross Blue Shield plans—often find it more advantageous to negotiate prices with manufacturers directly rather than relying on a PBM. Whatever their approach to price negotiations, when it comes to the distribution of specialty drugs to patients, most health plans contract with specialty pharmacies, since these entities have expertise on such matters as special drug handling and patient education.

Some specialty drugs are eligible for rebates on top of the discounted prices. These rebates are typically negotiated by whichever entity—PBM or health plan—is responsible for setting up the formulary and are paid to that entity after the drug has been purchased. Manufacturers are much more likely to offer rebates in drug classes where substitutes are available—for example, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis and growth hormone deficiency. The size of rebates typically depends on the PBM or health plan’s willingness to grant the drug preferred-product status and place it in lower cost-sharing tiers.

Even after discounts and rebates, specialty drug prices remain very high because, within most therapeutic categories, there tends to be at most a few drugs, which typically are imperfect substitutes for one another, and each drug is made by a single manufacturer. As a result, payers have little, if any, ability to exert pressure on price. Manufacturers justify high prices by citing the risk and high expense of successfully bringing a specialty drug to market. Also, the rarity of many conditions treated by specialty drugs means that these high development costs have to be spread across a relatively small population.

For self-insured employers seeking to obtain the lowest unit prices for specialty drugs, a key challenge is how to ensure that their PBMs pass through the discounts negotiated with manufacturers. While this is an issue whether the PBM is a health plan or a standalone PBM, experts noted that pass-through is a special challenge for employers when dealing with the largest standalone PBMs. The volume of their businesses allows these companies to negotiate the steepest discounts, but they reportedly have the least tendency to pass on savings to employers.

The contracts between employers and PBMs specifying specialty drug lists and pricing are highly complex and lack transparency, and even large employers tend to “lack the technical sophistication to identify areas where [the PBM] is charging a lot more than it should,” according to one specialty pharmacy consultant. One example involves PBMs specifying broad discounts per drug class rather than a specific drug—an approach that allows them to charge the employer large markups on older drugs whose prices have fallen substantially over time. Another example has to do with contract terms for adjunctive therapies—which are not specialty drugs themselves, but need to be used in conjunction with specialty drugs. An example is a nausea-relieving drug used alongside many cancer treatment drugs. Experts noted that while it may be appropriate to include such adjunctive therapies on specialty drug lists, PBMs often charge an excessive markup on these drugs. Because of such issues, market observers noted that sophisticated, ongoing scrutiny of employer-PBM contracts is needed, often by independent, specialized consultants who keep up to date on fast-changing developments in specialty drugs and their prices.

Changing provider payment. For specialty drugs covered under the medical benefit, the prevailing practice is for providers to purchase the drug, administer it and then bill the health plan at a markup. This practice, known as “buy and bill,” has been especially prevalent among oncologists administering cancer drugs. In large part to eliminate high buy-and-bill markups, plans have tried, over the past several years, to move office-administered specialty drugs from the medical benefit to the pharmacy benefit. Under the pharmacy benefit, the specialty pharmacy purchases the drug, bills the health plan, and either dispenses it to the provider or to the patient who must bring it to the provider for administration.

Plans making this transition have faced strong pushback from many providers—notably oncologists—who depend on buy-and-bill markups for a substantial portion of revenues and incomes.8 Providers often demand increases in payment rates for other services to make up for lost buy-and-bill revenues. Providers sometimes threaten to leave the health plan network—a special concern when the provider, such as a specialty group practice, accounts for a large share of a particular specialty in a market. As a result, some plans reportedly have reversed decisions to move drugs out of the medical benefit, while others have found that the switch saved them less than expected.

Instead of eliminating buy-and-bill practices altogether, some health plans are keeping specialty drugs under the medical benefit but reducing the markup through different approaches. One approach is to require providers to purchase specialty drugs from the plan’s contracted specialty pharmacy, which has negotiated a certain price for the drug. A similar approach is to impose a fee schedule on specialty drugs prescribed by providers, who remain free to buy drugs from a supplier of their choice but are only reimbursed at a fixed price set by the plan. This follows the approach set by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for office-administered drugs reimbursed under Medicare Part B.9 As with the elimination of buy-and-bill practices, these strategies risk triggering showdowns with providers, who may demand higher payment rates for other services or may consider abandoning the health plan’s network. Several regional Blue plans—whose dominant market shares gave them leverage over providers—first pioneered these approaches to reducing provider markups; after the ground was broken, other plans—including several nationals—followed suit.

In addition, several health plans have introduced incentive programs to influence provider prescribing patterns. In a few therapeutic classes where close substitutes with very different prices exist—for example, the taxane class of cancer drugs—plans are switching from the conventional method of paying providers a percentage of each drug’s cost, which favors prescribing the more costly drug, to an incentive system where providers receive at least as much—and sometimes significantly higher—payment for prescribing the less-expensive drug. This strategy, which has been described as “a hybrid approach. partly pricing, partly UM [utilization management],” is expected to grow as substitutes become available in more drug classes.

The costs borne by payers for injectable and infusible drugs vary substantially depending on the setting where the drugs are administered. Some plans steer patients to less-costly settings, such as ambulatory infusion centers, often through the use of patient cost-sharing incentives. Another approach used by some plans involves switching patients from clinician-administered infusible drugs to self-administered injectable substitutes. However, recent technological advances in specialty drugs have largely superseded these initiatives: Oral drugs have been introduced over the past several years that carry unit price tags far exceeding those of existing injectable and infusible substitutes. For example, oral chemotherapy drugs delivered in even the most-efficient setting will typically still cost substantially more than older infusible substitutes delivered in the most-expensive setting.

Other innovations. Drug pricing strategies used in other countries include direct price controls and various forms of value-based purchasing. Price controls are widely used by single-payer systems to determine price levels for prescription drugs. However, this approach is not an option for the U.S. commercial insurance market’s many payers, which have no control over market entry for drugs—given the unwillingness of most employers to restrict their formularies.

Reference pricing is one of the most established forms of value-based purchasing strategies for pharmaceuticals. Widely used in several countries, reference pricing is an approach where payers set a ceiling (reference) price within a class of drugs considered clinically equivalent and interchangeable. Consumers choosing a drug with a higher price than the reference price are responsible for paying the entire price differential out of pocket. Even in countries where reference pricing is widely used for conventional drugs, its use for specialty drugs is limited by the dearth of therapeutic classes where true substitutes exist.10 As biosimilars—generic substitutes for biologic drugs (see box below for more about biosimilars)—become available, more opportunities are expected to emerge for reference pricing, as well as tiered cost sharing and other approaches. However, proving therapeutic equivalence will be a key challenge, especially for biologic drugs, which are highly complex and sensitive to minor manufacturing variations.

Another form of value-based purchasing, outcomes-based contracting (OBC), is also used in some European countries with single-payer systems, where drug manufacturers accept such contracts to gain market entry for new drugs. OBC requires manufacturers to bear substantial risk—such as future exclusion from coverage and financial liability—based on patient outcomes. In the U.S. commercial market, competition among payers makes it unfeasible to use formulary exclusion as a tool in commercial products. As a result, manufacturers have little, if any, incentive to negotiate OBCs with commercial payers.

A few health plans in the United States are experimenting with outcomes-based contracts. However, these contracts are structured very differently from the OBCs in Europe. Under these agreements, the discounts are tied to the plans’ ability to demonstrate their members’ drug regimen adherence and reductions in relapses. This approach, then, appears to be more of an extension of the volume discounts granted by drug manufacturers to gain market share, rather than a true OBC approach of putting the manufacturer at financial risk based on evidence of drug effectiveness.

Finally, some countries, such as the United Kingdom, are experimenting with a particular form of value-based purchasing called “value-based pricing,” which uses comparative-effectiveness research (CER) data to vary price controls for manufacturers and cost-sharing levels for patients. As with other value-based purchasing strategies, the applicability of this tool for specialty drugs is limited by the dearth of substitutes. In addition, it requires CER data, which is not mandated in the U.S. drug regulatory approval process. As a result, manufacturers have no incentive to provide such evidence. In addition, the price-control aspect of this strategy is not available to U.S. commercial payers, as noted previously.

In summary, some value-based purchasing approaches have potential to become useful cost-containment tools for specialty drugs, but that potential depends largely on the development of more close substitutes in each therapeutic class—particular less-costly biosimilars.

BiosimilarsA biosimilar—also referred to as a biogeneric or a follow-on biologic—is a generic substitute for a previously approved biologic drug and is made by a different manufacturer following patent expiration of the original innovator drug. Unlike generic substitutes for conventional (small-molecule chemically synthesized) drugs, which are identical to their brand-name counterparts, the molecular complexity of biologics and their sensitivity to small changes in the manufacturing process makes truly identical products unlikely. Instead of requiring interchangeability, the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA), signed into law in 2010, requires that biosimilars have no clinically meaningful differences in safety, purity and potency from the original innovator drug. This law grants 12-year exclusivity to the drug manufacturer of the innovator product. Separately, each innovator drug is protected by a patent, whose protection period typically exceeds the market exclusivity period by at least a few years. BPCIA’s market exclusivity provision grants a minimum period of protection to the innovator drug in the event that a patent is proven invalid.11 The Food and Drug Administration is still in the process of establishing an approval pathway for biosimilars. Many believe the FDA regulations will be modeled on criteria used by the European Union, which has approved 13 biologics since establishing its pathway in 2005. Although the FDA approval pathway still has to be finalized, clinical research on biosimilars is already underway. There are a few examples of biosimilars already available in the United States. These are limited to simple biologics, such as insulin and growth hormone, whose substitutes were granted an abbreviated approval pathway by the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, commonly known as the Hatch-Waxman Act, the same legislation that established a system for generic versions of conventional drugs. |

![]() tilization management. Specialty drugs covered under the pharmacy benefit are subject to more pervasive and stringent utilization management (UM) than those under the medical benefit. Prior authorization, for example, is widely practiced—“nearly universal,” according to one respondent—under the pharmacy benefit but far less prevalent under the medical benefit, where retrospective review remains more common. One benefits consultant estimated that specialty drugs under the medical benefit are subject to prior authorization only about 5 percent of the time.

tilization management. Specialty drugs covered under the pharmacy benefit are subject to more pervasive and stringent utilization management (UM) than those under the medical benefit. Prior authorization, for example, is widely practiced—“nearly universal,” according to one respondent—under the pharmacy benefit but far less prevalent under the medical benefit, where retrospective review remains more common. One benefits consultant estimated that specialty drugs under the medical benefit are subject to prior authorization only about 5 percent of the time.

A major reason is that most contracts between health plans and providers contain no provisions for prior authorization or other UM protocols for specialty drugs under the medical benefit. Health plans are concerned that pushing to add a prior-authorization provision will result in provider resistance and perhaps provider exit from health plan networks. As with provider payment methods discussed previously, respondents suggested that implementing prior authorization under the medical benefit appears to be easier for regional Blue Cross Blue Shield plans whose large market shares give them leverage over providers.

Information technology poses another key barrier to prior authorization. WellPoint is one of the plans that has an Internet portal allowing providers to submit and receive authorization for specialty drug orders in real time. For the many plans that lack this real-time data capability, however, the use of prior authorization would entail more administrative expenses and also might delay physicians’ ability to implement or change drug regimens—a serious issue when dealing with extremely sick patients with complex conditions who often need on-the-spot medication adjustments during office visits.

The types of UM tools employed for specialty drugs tend to differ from those used for conventional drugs. Step therapy, where lower-cost options must be tried first, is commonly applied to conventional drugs but plays much less of a role for specialty drugs, because of the dearth of substitutes and the lack of CER evidence. However, quantity limits—often in the form of 15-day or 30-day supply limits—are nearly universal for specialty drugs under the pharmacy benefit, because of the need to ensure dosage safety and to minimize waste of expensive drugs in case drug regimens need to be changed—a frequent occurrence with specialty drugs.

Over the past several years, there has been increasing interest in extending the full range of UM tools already in use under the pharmacy benefit to drugs covered under the medical benefit. This is part of a larger effort to integrate medical and pharmacy benefits for specialty drugs. However, efforts to impose more UM on drugs under the medical benefit have been hampered by important limitations, including the lack of detailed, reliable claims information about office-administered drugs under the medical benefit.

Each drug billed under the pharmacy benefit is identified by a National Drug Code (NDC), which specifies the drug name, manufacturer, dosage form, strength and package size. In contrast, drugs billed under medical claims are identified using far less specific Health Care Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes, which are unique only to a drug’s chemical name, but not to its manufacturer, dosage strength or package size. And, unlike the NDC number, which becomes available when the drug receives FDA approval and before it enters the market, HCPCS codes are not defined until six to 18 months after the drug has been launched. Drugs administered in the interim under the medical benefit are billed to a general “unclassified” code. As a result, the HCPCS system does not allow payers to track and manage utilization the same way they can under the pharmacy benefit.12 In response, some health plans are rewriting provider contracts to require NDCs on medical claims. However, this approach has met with some provider resistance and has been hampered by the inability of some claims and billing systems to accommodate the 11-digit NDCs.

Even if all specialty drugs billed under medical claims can be converted to the NDC system, integration of medical and pharmacy utilization data poses serious challenges. These challenges tend to be especially acute when the pharmacy and medical benefits are managed by two different entities, with a health plan (medical carrier) managing medical benefits and a separate PBM overseeing pharmacy benefits. Contracts with self-insured employers often require the medical carrier and PBM to share data with each other, but even when both entities cooperate, experts noted that data lags of at least two weeks are more the norm than real-time data sharing.

Experts generally viewed health plans—even when just acting as medical carriers on behalf of self-insured employers—as more aggressive in managing specialty drug utilization than standalone PBMs. The latter were widely perceived as having little incentive to keep utilization of high-cost drugs in check. As one benefits consultant observed, PBMs “earn a margin on each prescription filled. that’s the core of their business, so you wouldn’t expect them to scrutinize [utilization] too carefully.”

Care management. Experts viewed strong clinical care management as critical to promoting both good health outcomes and cost containment. Key challenges include very sick patients with complex chronic conditions requiring complicated drug regimens, the need to adjust drugs or fine-tune dosage, and strong side effects leading patients to abandon drug regimens. Experts cited cancer and hepatitis C as examples where medications caused such unpleasant, sustained side effects that keeping patients compliant over time was particularly difficult. Several respondents emphasized the importance of a “high-touch” approach to care management, where staff not only has clinical expertise but also the ability to “form personal connections with patients” and motivate them to adhere to demanding drug regimens.

As is the case for utilization management, the lack of integration between medical and pharmacy benefits creates barriers to effective and coordinated care management. For specialty drugs covered under the medical benefit, a patient’s physician is responsible for major care management activities, including patient education, dosage monitoring and managing side effects, but other care management aspects are likely to fall under case management or disease management programs overseen by a health plan or a separate vendor. Coordination among these entities is typically far from optimal, and “some [care management] services are duplicated. [while] others fall through the cracks,” according to one health plan executive. Even for specialty drugs covered only under the pharmacy benefit, coordination of care management activities still poses challenges. For example, the specialty pharmacy handles patient education, dosage monitoring, side-effect tracking, and coordination with the patient’s physician about drug regimens, while the health plan or PBM is responsible for other aspects of care management related to the patient’s medical condition.

Unlike utilization management, PBMs were seen by most respondents as having an edge over health plans in key aspects of care management, such as overseeing and tweaking complicated drug regimens and conducting outreach to physicians and patients. However, several experts cautioned that the effectiveness of any single PBM in performing care management fluctuated substantially across the many health conditions that specialty drugs are used to treat.

Innovations. Many respondents noted that the introduction of biosimilars—still many years away—will make it possible to apply step therapy more broadly as part of specialty drug management. However, several experts noted that step therapy will be less straightforward for specialty drugs than conventional drugs, because therapeutic equivalence across drugs will be difficult to determine, and small differences in biotechnology manufacturing processes can lead to important differences in how patients respond to treatments.

A promising innovation already underway involves health plans working with physician specialty societies and other provider organizations to establish clinical pathways, which include drug regimens and other care protocols, for particular disease states. For example, several large national plans and regional Blue plans have implemented clinical pathway programs for different kinds of cancer. Instead of imposing UM protocols on providers in a top-down approach, this is a more collaborative approach. Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan is among the plans to reward provider groups that successfully adopt clinical pathways, through its pay-for-performance Physician Group Incentive Program.

Another innovation involves the use of smaller, specialized specialty pharmacies that have expertise in specific, complex disease states. However, the ability of employers to use these niche specialty pharmacies is constrained by their existing contracts with the PBMs managing the employers’ pharmacy benefits. In most contracts, the PBM either prohibits disease-specific carve-outs outright or increases its own pricing if the employer opts for disease-specific carve-outs. As a result, respondents noted that the only employers currently able to use these niche specialty pharmacies appear to be hospital systems, which are not dependent on large PBMs to negotiate drug discounts because they are able to obtain favorable so-called “class of trade” drug pricing directly from manufacturers.

![]() mong the common themes that emerged from interviews with industry experts, the following stand out:

mong the common themes that emerged from interviews with industry experts, the following stand out:

Key drug management strategies that have proven effective for conventional drugs often are less applicable to specialty drugs: The lack of close substitutes for most specialty drugs greatly reduces, or eliminates altogether, the ability of tools like cost-sharing tiers and step therapy to steer patients and providers to cost-effective alternatives. It also sharply limits incentives for drug manufacturers to offer substantial price concessions. In contrast, other tools, such as prior authorization and quantity limits—which can help curb unnecessary or inappropriate use, improve patient safety, and reduce waste—are emphasized more in the management of specialty drugs.

Biosimilars are expected to lead to key breakthroughs in specialty drug management, but their impact won’t be seen for many years: The introduction of generic substitutes should allow payers to broaden the use of preferred drug tiers and step therapy, thereby exerting downward pressure on prices. However, achieving therapeutic equivalence—for biosimilar manufacturers—and assessing therapeutic equivalence—for regulators—are likely to be difficult, given the complex nature of biologics. Also, the expensive manufacturing process means that biosimilars may not yield savings as sizable as those achieved by conventional generic drugs. And, it will be an uncertain number of years before biosimilars can make an impact on competition and cost, because (1) innovator products are granted 12 years of market exclusivity and often are protected by patents lasting years beyond that; and (2) the FDA approval process—which has yet to be finalized—is expected to be rigorous and lengthy.

Integration of medical and pharmacy benefits is a goal worth pursuing, but how to achieve it isn’t clear: Efforts to overhaul the currently fragmented benefit structure—which can misalign incentives for patients and providers and result in uncoordinated patient management—are in the early stages of development, and results are uneven at best. Equalizing patient cost sharing for specialty drugs regardless of whether they are covered under the pharmacy or medical benefit is probably the most straightforward dimension of integration. Other aspects of integration present tougher challenges. The ability to track utilization and spending under the medical benefit remains limited, which in turn hinders the ability to manage a large segment of specialty drug utilization. Real-time integration of utilization data remains hampered by limitations in claims and billing systems. Also, as office-administered drugs are moved out of the medical benefit’s buy-and-bill approach, health plans will have to deal with fallout from physicians who see both their margins and clinical autonomy eroding.

Patient adherence is critical to good health outcomes: As one pharmacy consultant observed, “Price tags and performance guarantees [from PBMs] are one thing, but if you [can’t achieve] compliance, it’s all a waste.” Both financial factors—high out-of-pocket costs—and nonfinancial factors—strong side effects—pose formidable barriers to patient adherence and positive health outcomes. A combination of non-punitive cost sharing and strong care management may reduce these barriers. One benefit design approach that can help make financial burden more manageable is an income-based cost-sharing structure.

Employers should ensure that their specialty drug strategies are aligned with their overall benefits and business strategies: Decisions on specialty drug coverage require tough trade-offs between cost and access. Which cost-access combination an employer chooses will be heavily influenced by competitive conditions in the industry and the geographic and labor markets where an employer operates. Short-term cost containment can have unintended consequences—for example, increased cost sharing leading to reduced adherence to drug regimen, in turn leading to high-cost complications. Such negative impacts come more into play for employers with low worker turnover and those still offering comprehensive retiree health benefits, as these are the employers likely to be paying the bill in the long term for patients currently taking specialty drugs. Cost-benefit comparisons of different drug coverage options will be more accurate if they are able to account for impact on employee productivity—which is hard to measure—as well as direct medical costs.

PBMs’ interests may not align with employers’ interests: Some employers may be relying heavily on their PBMs to set specialty drug policies, determine specialty drug lists, and pass through discounts from manufacturers, without independently verifying whether their own needs are best served in these arrangements. Employers need to recognize that PBMs’ interests can diverge sharply from their own interests, as PBMs don’t have the same incentives as employers to limit the volume and the prices of drugs. Because the specialty drug sector is complex and the vast majority of employers lack the in-house expertise to deal with PBMs on an equal footing, many employers likely would benefit from having independent experts assess their PBM contract terms and audit compliance with those terms.

![]() pending on specialty drugs is expected to skyrocket over the next decade and beyond, as some of the hundreds of biologics currently in the pipeline gain approval and hit the market. The number of conditions that can be treated with specialty drugs—and thus the number of patients eligible for treatment with these high-cost drugs—are both expected to soar. These developments will intensify the cost and access trade-offs that payers and purchasers already face.

pending on specialty drugs is expected to skyrocket over the next decade and beyond, as some of the hundreds of biologics currently in the pipeline gain approval and hit the market. The number of conditions that can be treated with specialty drugs—and thus the number of patients eligible for treatment with these high-cost drugs—are both expected to soar. These developments will intensify the cost and access trade-offs that payers and purchasers already face.

People who enroll in coverage through health insurance exchanges beginning in 2014 will find access to specialty drugs varying substantially across states, depending on the decisions that each state makes regarding benchmarks for essential health benefits. If a state chooses the Federal Employees Health Benefits plan as the benchmark, this plan’s open formulary will ensure that enrollees have coverage for all FDA-approved drugs; in contrast, state benchmarking to small-group products will result in less comprehensive drug coverage.13 Another important question for specialty drug users will be their out-of-pocket exposure. The guidance recently released by the Department of Health and Human Services on actuarial value leaves insurers a great deal of latitude on how to specify cost-sharing levels for particular services; thus, exchange products with the same actuarial value may differ markedly in cost sharing for prescription drugs. What already seems clear is that specialty drug users will be among the population of sick enrollees who are most likely to choose plans with the most generous coverage—the platinum and gold plans, with 90 percent and 80 percent actuarial values, respectively. As the sickest enrollees sort themselves into the most generous plans, it could generate a so-called death spiral, where premiums for those plans may increase unsustainably over time.

Payers are looking to biosimilars to provide some relief from soaring specialty drug costs in the future. However, that relief may take many years to arrive, as federal law grants original brand-name biologics 12 years of market exclusivity, and many biologics are protected by patents for years after exclusivity expires. Some observers and stakeholders, including the Federal Trade Commission, believe that a period significantly shorter than 12 years would be sufficient to promote innovation; the Obama administration has proposed shortening the exclusivity period to seven years.14 It may be useful for policy makers to revisit this issue, balancing the need to promote drug innovation against the priority of making relatively affordable substitutes available in a timely manner.

This Research Brief draws on interviews with representatives of a variety of organizations involved in specialty drug coverage and management. Initial information was gathered through HSC’s 2010 Community Tracking Study site visits, which included 174 interviews with health plans, benefits consulting firms and other private-sector market experts on a variety of topics. In addition, HSC researchers conducted literature reviews and conducted an additional 20 in-depth interviews specifically on specialty drug management with more representatives from health plans, benefits consulting firms, pharmacy consulting firms and other industry experts. The additional interviews were conducted between June and September 2011, using a semi-structured protocol and a two-person interview team. Interview notes were transcribed and jointly reviewed for quality and validation purposes. Interview responses were coded and analyzed using Atlas.ti, a qualitative software tool.

The 2010 Community Tracking Study site visits were funded jointly by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the National Institute for Health Care Reform (NIHCR). Follow-up interviews and background research specifically on specialty drug management was funded by NIHCR.

RESEARCH BRIEFS are published by the Center for Studying Health System

Change.

1100 1st Street, NE, 12th Floor

Washington, DC 20002-4221

Tel: (202) 484-5261

Fax: (202) 863-1763

www.hschange.org