HSC Research Brief No. 24

November 2012

Emily Carrier, Tracy Yee, Dori A. Cross, Divya R. Samuel

Being prepared for a natural disaster, infectious disease outbreak or other emergency where many injured or ill people need medical care while maintaining ongoing operations is a significant challenge for local health systems. Emergency preparedness requires coordination of diverse entities at the local, regional and national levels. Given the diversity of stakeholders, fragmentation of local health care systems and limited resources, developing and sustaining broad community coalitions focused on emergency preparedness is difficult. While some stakeholders, such as hospitals and local emergency medical services, consistently work together, other important groups—for example, primary care clinicians and nursing homes—typically do not participate in emergency-preparedness coalitions, according to a new qualitative study of 10 U.S. communities by the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC).

Challenges to developing and sustaining community coalitions may reflect the structure of preparedness activities, which are typically administered by designated staff in hospitals or large medical practices. There are two general approaches policy makers could consider to broaden participation in emergency-preparedness coalitions: providing incentives for more stakeholders to join existing coalitions or building preparedness into activities providers already are pursuing. Moreover, rather than defining and measuring processes associated with collaboration—such as coalition membership or development of certain planning documents—policy makers might consider defining the outcomes expected of a successful collaboration in the event of a disaster, without regard to the specific form that collaboration takes.

![]() ince the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, many health care providers have adopted emergency-preparedness plans, including participation in such activities as community-wide drills and tabletop exercises, to strengthen their ability to respond to a disaster. Maintaining preparedness is a daunting task, given that emergencies can spring up at a national, regional or local level and take forms as varied as a global pandemic, a regional hurricane or a local outbreak of food-borne illness.

ince the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, many health care providers have adopted emergency-preparedness plans, including participation in such activities as community-wide drills and tabletop exercises, to strengthen their ability to respond to a disaster. Maintaining preparedness is a daunting task, given that emergencies can spring up at a national, regional or local level and take forms as varied as a global pandemic, a regional hurricane or a local outbreak of food-borne illness.

Health care providers’ focus on emergency-preparedness activities waxes and wanes, reflecting the many pressures and competing demands they face. While conducting normal operations, providers must prepare for low-probability, high-impact events that can sharply increase demand for care and stress capacity to the breaking point. While there is limited funding for preparedness activities, hospitals are not subsidized to keep beds empty and supplies stockpiled for a disaster, and it is impractical for trained staff to sit idle until a disaster strikes. As previous research shows, communities have compensated by trying to develop additional surge capacity in a manner that supports day-to-day activities and stretches existing resources in an emergency.1

Providers and policy makers alike increasingly have recognized the value of collaboration through community-based preparedness initiatives to minimize the amount of redundant capacity each provider must maintain. Community-level preparedness—meaning multiple stakeholders working together to prepare for, withstand and recover from both short- and long-term emergencies—can improve the quality and efficiency of emergency response by encouraging participants to coordinate with others and take advantage of their resources and skills.2

Community-based emergency-preparedness coalitions—which usually include hospitals, local public health departments and emergency management and response agencies and more rarely ambulatory clinics or long-term care providers—are intended to foster local preparedness and minimize the need for federal intervention. Coalitions are not intended to replace individual provider’s preparedness activities; rather, coalition participation augments a provider’s ability to respond to severe and catastrophic emergencies that would require a coordinated community, regional or national response for optimal patient outcomes.3

Using the lens of the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, this study examined the activities of emergency-preparedness coalitions in 10 U.S. communities (see Data Source and box below for more about the H1N1 pandemic). The H1N1 influenza pandemic was the most recent national event that required large-scale preparedness and response. As a prolonged, low-mortality event, H1N1 tested community preparedness, clarified the challenges different stakeholders face, and pointed to ways to broaden and strengthen local collaboration.

The H1N1 ExperienceThe first case of H1N1 influenza in the United States was recorded April 15, 2009, in California. By April 26, the government determined that H1N1 represented a national public health emergency and began releasing stores of personal-protective equipment and antiviral medications to states from the strategic national stockpile. The spring phase of H1N1 peaked in May and June 2009, with a slight decline before picking up again in late August. The fall wave was larger in magnitude, and cases continued to rise until late October. Vaccines were available by early October 2009, at first for high-risk populations only, but more widely by December as supply increased. Cases dipped below baseline levels by January 2010, and the U.S. Public Health Emergency for 2009 H1N1 Influenza expired on June 23, 2010. Throughout this time, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) worked to promote communication among partners via conference calls with national organizations representing state and local health agencies, clinician outreach activities, listservs, newsletters, and hearings. In some cases, the CDC altered guidance as data emerged, for example, reversing a recommendation to close schools for suspected or actual cases once the lower risk of severe illness became known. Respondents reported that CDC guidance was generally well received, and nearly all respondents turned to the CDC on a regular basis during the H1N1 pandemic for information and guidance. |

![]() rganizations participating in community-level preparedness face many challenges. First, preparedness activities, such as planning, training and participating in drills, do not generate revenue for health care providers but have costs in staff time and materials. Given the low probability of certain events, stockpiling supplies and committing staff to emergency preparedness often are not high institutional priorities.4 In addition, community coalitions require competitors to work collaboratively. And, unlike other events that health care organizations must prepare for, such as Joint Commission inspections, there are no predictable, short-term consequences for failing to engage in collaborative, community-level disaster planning.

rganizations participating in community-level preparedness face many challenges. First, preparedness activities, such as planning, training and participating in drills, do not generate revenue for health care providers but have costs in staff time and materials. Given the low probability of certain events, stockpiling supplies and committing staff to emergency preparedness often are not high institutional priorities.4 In addition, community coalitions require competitors to work collaboratively. And, unlike other events that health care organizations must prepare for, such as Joint Commission inspections, there are no predictable, short-term consequences for failing to engage in collaborative, community-level disaster planning.

A number of different federal, state and local organizations work with health care providers individually and collectively to promote collaboration in preparedness activities. One of the most important post-9/11 funding sources for these coalitions is the Hospital Preparedness Program administered by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (see box below for more about funding sources). The focus on hospitals reflects their historic importance in providing staff, space for planning and response, and treatment of emergency victims, including such specialized services as decontamination or burn care. Physicians and other clinicians employed by hospitals or working in community-based practices owned by hospitals usually fall under the umbrella of hospital preparedness activities. Likewise, so-called first responders—police, fire and emergency medical services (EMS)—typically work closely with hospitals to transport patients to a site with the necessary staff and infrastructure to treat their conditions.

In contrast, much less attention and funding have focused on involving other health care providers, such as independent physician practices, ambulatory care centers, specialty care centers and long-term care facilities, in community-based preparedness activities. Few communities involve independent practitioners other than maintaining a list of those willing to volunteer in the event of a disaster, for which no special training or expertise in disaster response is required. Regional or specialty-based medical societies may maintain similar lists and can provide basic training in disaster planning through continuing medical education. In certain types of emergencies, particularly those related to infectious disease—for example, an influenza pandemic or a severe, local norovirus outbreak—independent, community-based clinicians may care for many affected patients in their practices, and their triage and treatment decisions can influence an emergency’s impact on hospitals. Even in a disaster where victims seek care at hospitals, community-based clinicians can play a role. For example, in a disaster, hospitals generally try to discharge as many inpatients as possible, and community-based providers could help by seeing or contacting discharged patients to ensure they are receiving needed follow-up care.

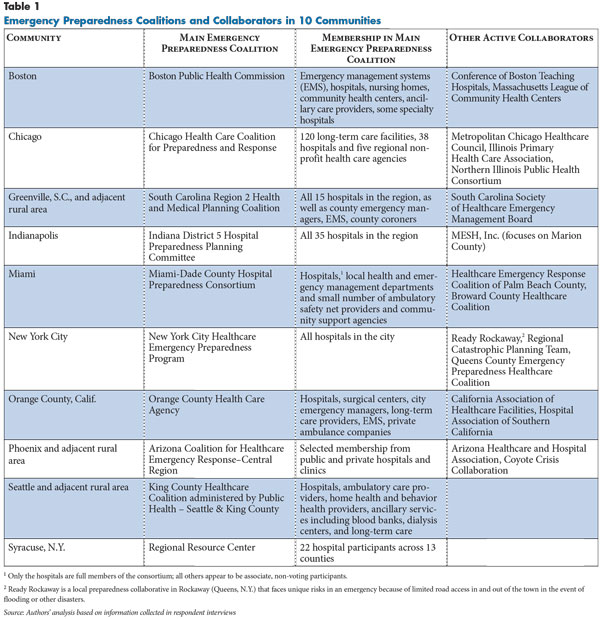

While hospitals and public health departments participated in all emergency-preparedness coalitions in the communities studied, involvement of nonhospital providers and other stakeholders varied significantly across the communities (see Table 1). Nonmedical stakeholders, such as police, fire, coroners, school systems and employers, have varying degrees of involvement in medical emergency planning collaboration. One community, Greenville, reported heavy involvement from the coroner’s office, while another, New York City, worked with large employers.

A lack of collaboration among stakeholders reportedly has contributed to problems. For example, respondents in four communities—Boston, Chicago, Greenville and Indianapolis—reported challenges working with local school systems, citing coordination and communication difficulties during the H1N1 pandemic. According to a Chicago respondent, "Some schools told people that kids couldn’t come back to school without a doctor’s note. Hundreds of people went to ERs for a doctor’s note."

When working with nontraditional partners, community coalitions reported difficulty in aligning goals and securing buy in from those who view emergency management as outside their scope of responsibility. For example, one community coalition reported contacting long-term care facilities to offer funding to stockpile antiviral medication but found no takers. A hospital respondent in another community coalition cited reluctance to work with nursing homes because of the perception that they are primarily looking for a place to offload patients in an emergency.

However, such stakeholders as schools and employers can and do influence medical treatment during disasters. Some offer on-site health care, which may serve as an alternate source of care that is not always coordinated with hospitals or independent practices, and others may require documentation from a clinician before potentially affected people can return to school or work.

Agencies and Programs Supporting Emergency-Preparedness Planning and ResponseU.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR)

HHS Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response

U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)

Other

|

![]() ospital-based physicians reported working well together on preparedness efforts, notwithstanding occasional tensions surrounding communication with each other and other providers. Yet, despite common agreement that primary care providers could play an important role in surge capacity, respondents across the board reported minimal involvement of independent primary care providers in emergency-preparedness coalitions or activities. One respondent explained that, “[Primary care] doctors are busy and often don’t see the implication and impact of mass emergencies on their practices.”

ospital-based physicians reported working well together on preparedness efforts, notwithstanding occasional tensions surrounding communication with each other and other providers. Yet, despite common agreement that primary care providers could play an important role in surge capacity, respondents across the board reported minimal involvement of independent primary care providers in emergency-preparedness coalitions or activities. One respondent explained that, “[Primary care] doctors are busy and often don’t see the implication and impact of mass emergencies on their practices.”

Small, independent physician practices were considered least able to participate in preparedness planning, with challenges including lack of time, funds, physical space that might be required during a disaster—for example, separate waiting areas to isolate potentially infectious patients—and in some cases, lack of leverage to purchase needed supplies. One independent practice leader described an experience during the H1N1 pandemic: “When supplies came in for patients, they were sent through the hospitals and would automatically go to their hospital-employed primary care physicians but not necessarily to physicians who had community offices.”

Both hospital and community practice respondents acknowledged a sense of alienation from each other, noting that the smaller the practice, the more difficult it is to participate and have a voice in community collaborations. According to respondents, state and local medical societies generally have not played an important role to date in helping small practices to collaborate with each other or other stakeholders.

Most primary care respondents agreed that physicians are focused mainly on their patients’ day-to-day needs and do not see preparedness as part of their mission. One independent practice physician said, “It really is a cowboy mentality out here, everybody riding their own horse, on their own ranch.” Even when individual physicians demonstrated an interest in emergency preparedness, they were often on their own in assembling resources. Larger practices, in contrast, reported designating resources to support preparedness. “The wonderful thing about working in a big group is someone can pay me to do this stuff,” one physician respondent said. “Whereas, my friend who has a partner and a couple nurse practitioners cannot [afford that].”

![]() espondents noted that certain local market characteristics may help predict successful community-level disaster response. Successful collaboration was most often attributed to strong pre-existing relationships, some of which were among otherwise competing organizations. Collaboration reportedly transcended day-to-day competition during preparations for potentially serious events. In some cases, this reflected a commitment at the highest levels of organizations, but, in other cases, it reflected rapport among preparedness staff. “Our CEOs can stick their tongues out at each other all they want, but we [the emergency-preparedness managers] are on the phone talking,” according to a hospital respondent. Other respondents reported frequent communication among competing hospitals on shared pandemic plans and hospital policies for emergencies.

espondents noted that certain local market characteristics may help predict successful community-level disaster response. Successful collaboration was most often attributed to strong pre-existing relationships, some of which were among otherwise competing organizations. Collaboration reportedly transcended day-to-day competition during preparations for potentially serious events. In some cases, this reflected a commitment at the highest levels of organizations, but, in other cases, it reflected rapport among preparedness staff. “Our CEOs can stick their tongues out at each other all they want, but we [the emergency-preparedness managers] are on the phone talking,” according to a hospital respondent. Other respondents reported frequent communication among competing hospitals on shared pandemic plans and hospital policies for emergencies.

A few respondents reported that competition did affect preparedness collaborations, particularly when hospital leaders are guarded about sharing capabilities and needs with peers at other institutions. “There are a few of my peers who share with me openly, but a few say their administration will not allow any of that information out,” a hospital-preparedness manager said, adding the guardedness primarily reflected concerns about losing a competitive advantage. However, respondents across all sites generally agreed that providers put normal competitive dynamics aside for preparedness efforts and meet and share information on capacity and supply chains when needed. While they were beset with other challenges, rural communities were particularly well positioned to take advantage of strong day-to-day relationships among providers (see box below for more about rural communities).

During the H1N1 pandemic, for example, some coalitions developed plans to distribute supplies in advance. In practice, sharing happened less formally; for example, a single institution would make a request through the coalition and another coalition member would respond. Many respondents noted issues with securing adequate amounts of personal-protective equipment. Hospital staff in nearly all sites reported challenges with fit-testing disposable protective face masks because of the staff time required and because fit-testing alone consumed a substantial proportion of their inventory. Maintaining adequate supplies, particularly of masks, was a challenge when hospitals in a community, as well as public agencies, were competing for the same products.

Ultimately, nearly all respondents agreed that successful coalitions require ongoing attention to relationships. If these networks are activated only in an emergency, the response will likely be poor. As one hospital-preparedness manager said, “Disasters aren’t the time to be exchanging business cards.” A few respondents who mentioned the role of public health field staff in their region also expressed interest in developing long-term relationships with those staff rather than meeting them only during disasters.

Nearly all hospitals working with both hospital-employed physicians and independent community-based physicians reported that hospital-employed physicians are easier to engage, suggesting that markets with larger physician groups and more hospital employment of physicians would be better positioned to build integrated surge-capacity plans. In some hospital systems, the system’s preparedness plan directly encompassed physician practices owned by the hospital system. In such systems, hospital staff typically created practices’ prepardness plans and implemented them; physicians in the practices were more passive participants. Some health systems did expect employed physicians in community practices to work collaboratively in disaster planning. High levels of physician participation in those markets were attributed to hospital systems setting the expectation that physicians would participate and paying them for their efforts, and, in some cases, even allotting them administrative time to participate in preparedness or other system-level work.

Because of the generally collegial approach to preparedness activities, respondents reported that tighter hospital affiliations in consolidated markets had little impact. However, hospitals’ size and market share may shape some aspects of preparedness. For example, a few respondents at independent hospitals in consolidated hospital markets—Indianapolis and Boston, for example—said their larger competitors received preferential treatment from suppliers of needed products, such as personal-protective equipment, during the H1N1 pandemic.

Rural Communities: Unique Challenges and StrengthsWhile all providers felt the strain of competing demands in allocating resources for emergency preparedness, rural providers were particularly strapped. Rural respondents reported depending on buy in from a smaller pool of institutional leaders, and these leaders did not always perceive value in allocating limited funding and staff time for emergency management and participation in coalitions. As one respondent said, “Rural hospitals are facing huge budgetary issues right now. It’s always difficult to spend money on something [like emergency preparedness] that doesn’t generate money. That’s the mentality at small as well as big hospitals, [but] you can multiply that by 100 for small [rural] hospitals. It’s very hard to get buy in.” Given these constraints, staff working on preparedness issues often filled many other roles as well—for example, as a safety officer—and were less involved in formal emergency preparedness coalitions. Some rural providers were creative in their resource-limited approach to preparedness. For example, outside Seattle, three small rural hospitals pooled funds to hire a shared emergency manager across the facilities. However, this position eventually was eliminated. In most cases, rural communities ultimately rely more on regional partnerships with state health departments and urban health care partners for mutual aid or access to stockpiles, even though those entities’ priorities typically are geared to more populous areas. No rural respondents described working with their state office of rural health on emergency preparedness. Respondents did report that local partnerships and emergency response in small towns were more cohesive because of strong day-to-day relationships among health care providers, first-hand knowledge of the population they serve and a strong community feel. As one rural South Carolina respondent noted, a small town in which people know and look after their neighbors can help responders identify and protect more vulnerable community members in an emergency situation. |

![]() ecent studies, including an Institute of Medicine report, have pressed for greater integration of public health and primary care.5 Developing community-level preparedness coalitions is one potential avenue toward that goal. However, most attention has focused on population-level management of obesity or chronic illness rather than disaster preparedness and response. At the same time, public health preparedness experts have sought to develop methods to evaluate community coalitions. This study’s findings suggest that preparedness work could be integrated with broader care delivery, with possible implications for how to evaluate coalitions.

ecent studies, including an Institute of Medicine report, have pressed for greater integration of public health and primary care.5 Developing community-level preparedness coalitions is one potential avenue toward that goal. However, most attention has focused on population-level management of obesity or chronic illness rather than disaster preparedness and response. At the same time, public health preparedness experts have sought to develop methods to evaluate community coalitions. This study’s findings suggest that preparedness work could be integrated with broader care delivery, with possible implications for how to evaluate coalitions.

Across sites, respondents consistently reported that hospitals and hospital-owned physician practices typically are much more involved in emergency-preparedness coalitions than other stakeholders, reflecting both the federal financial support hospitals receive for preparedness activities and their size, structure and resources. Other stakeholders, particularly smaller and independent primary care practices, could potentially contribute to preparedness efforts, but there are significant barriers to involving them in traditional coalitions in a sustainable way.

There are two general approaches policy makers could consider to broaden participation in emergency-preparedness coalitions: providing incentives for more stakeholders to join existing preparedness coalitions or building preparedness into activities providers already are pursuing.

Providing incentives to participate in traditional preparedness coalitions. Policy makers could encourage groups whose participation is currently limited in most communities, such as independent physician practices, to join traditional preparedness coalitions that meet regularly to develop joint plans or coordinate responses. One approach could be to provide funding aimed directly at supporting independent physicians’ and other underrepresented stakeholders’ participation. However, lack of funding—while an important problem—is not the only barrier to these groups’ involvement. Lack of time, training and sometimes simply awareness that they have a role in disaster response also are important factors. Even if the CDC and other agencies could secure sufficient funds, they would be competing against many other incentive programs aimed at physician practices—for example, adoption of health information technology, greater care coordination and performance improvement.

Some community-based physicians and other clinicians, such as those working in large practices or affiliated with large independent practice associations, are able to participate in traditional coalitions despite these challenges. In communities where these types of practice arrangements are common, participation may be sufficient to generate broad-based coordination through traditional coalitions. Changes in local market structures, such as increased hospital employment of physicians, also may diminish barriers in some communities.

There may be few alternatives for small primary care practices in fragmented markets to participate in traditional coalitions. Policy makers seeking to broaden collaboration in these communities might consider such approaches as sending trained staff to visit practices to describe the benefits of preparedness activities and help practices join coalitions. Pharmaceutical and device manufacturers often use this approach—known as detailing—by sending sales representatives to practices to explain the use—and encourage the purchase—of their products. Community-level preparedness workers also could identify key physician opinion leaders, who are sometimes but not always affiliated with state and local medical societies in these communities, for informal outreach. Particularly in smaller markets and those with lower turnover in health care providers, persuading key opinion leaders may be the most efficient way to encourage broad participation in traditional coalitions.

Consider building preparedness into activities providers already are pursuing.An alternative approach to traditional preparedness coalitions would be to leverage activities providers already are pursuing unrelated to preparedness activities. “Don’t start a new group,” said one public health employee of working with independent practices. “They don’t have time. You need to get on the agenda of existing forums. Find out who runs them, have something to say, and then get on their agenda regularly. Be part of the meeting group, and then quarterly, get on the agenda. Let them know, ‘Here’s what we’re doing; here’s how it relates to you.’”

One option would be to incorporate preparedness activities into existing incentive programs aimed at underrepresented stakeholders, including independent physicians and nursing homes. For example, programs that offer extra payment to primary care practices to coordinate care of patients with specific chronic conditions might also encourage and reward coordination related to emergency preparedness or the creation of business continuity plans. Likewise, hospital efforts to work with physician practices and long-term care facilities to prevent avoidable readmissions might incorporate preparedness activities.

Other opportunities might include incorporating community-level preparedness activities into care-coordination activities that can count toward patient-centered medical home certification or encouraging electronic health record vendors to include features that facilitate electronic submission of important data to local, state and federal authorities during a disaster.

If collaborative preparedness activities leveraged existing affiliations and activities among stakeholders, the resulting coalitions might look very different from community to community. Employment of physicians is only one of the ways markets vary—hospitals may be independent or tightly affiliated with one another, nursing homes may be closely linked to local hospitals or to national chains, and health information may be shared widely or not at all. Each of these factors may affect how planning responsibilities, staff and information are most efficiently shared in preparation for and during a disaster.

For example, nursing homes owned by or closely affiliated with hospitals may use the hospitals’ preparedness staff, making it easy to develop collaborative approaches to preparedness. Similarly, hospitals and physician practices using a common electronic health record platform may find it easier to share real-time information about utilization and to prepare jointly for surges. It is important to note that collaborations based on existing affiliations and less-formal relationships would still require some oversight to avoid situations where disparities in market position may leave some providers at a disadvantage in securing needed information and supplies during a disaster.

Given the characteristics of different health care providers—large or small, integrated or independent—different levers will be most effective in encouraging change in different communities. There is no one-size-fits-all approach, and coalitions alone may not meet the needs of some communities, particularly those with extremely fragmented physician and other health care sectors. Instead, policy makers may want to emphasize outcomes, such as safe, efficient management of surge demand or receipt of needed information by stakeholders, and allow communities flexibility regarding processes and participants.

At this time, it is difficult to say which—if any—of these approaches will be most effective in encouraging broad-based coalitions that can effectively respond to emergencies. Likely, there is no single solution that meets the needs of all types of communities. This would make sustainable collaboration difficult to monitor objectively, which could be important if policy makers intend to link sustainable collaboration to grants or other funding sources or design formal methods to identify and qualify participation by particular stakeholder groups. Rather than defining and measuring processes associated with collaboration—such as coalition membership or development of certain planning documents—as is the focus of the current Hospital Preparedness Program and CDC Public Health Emergency Preparedness Program,6 policy makers might consider defining the outcomes expected of a successful collaboration in the event of a disaster. Developing ways to measure the real-world outcomes of disaster response efforts before a disaster occurs will be an important next step.

This study examined the activities of community-based emergency-preparedness coalitions in 10 communities. Eight of the communities were chosen from the Community Tracking Study (CTS), an ongoing study of local health care markets in 12 nationally representative metropolitan communities. Based on preliminary findings from the 2010 CTS site visits, as well as data collected for a related study on surge capacity in 2008, researchers selected eight communities that demonstrated a significant level of activity related to emergency preparedness and provided broad geographic representation: Boston; Greenville, S.C.; Indianapolis, Miami; Phoenix; Orange County, Calif.; Seattle; and Syracuse. Rural communities adjacent to the Greenville, Phoenix and Seattle markets were included as well. Two additional sites were added: New York City because of significant investment in preparedness and Chicago to increase Midwestern representation. Sixty-seven telephone interviews were conducted between June 2011 and May 2012 with representatives of state and local emergency management agencies and health departments, emergency-preparedness coalitions, hospital emergency preparedness coordinators, primary care practices and other organizations working on emergency preparedness and response. A two-person research team conducted each interview, and notes were transcribed and jointly reviewed for quality and validation purposes.

This research was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). This document was prepared for CDC by the Center for Studying Health System Change under Contract No. 200-2010-35788. The study findings and conclusions are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.