HSC Research Brief No. 25

November 2012

Laurie E. Felland, Lucy B. Stark

Over the last 15 years, public hospitals have pursued multiple strategies to help maintain financial viability without abandoning their mission to care for low-income people, according to findings from the Center for Studying Health System Change’s (HSC) site visits to 12 nationally representative metropolitan communities. Local public hospitals serve as core safety net providers in five of these communities—Boston, Cleveland, Indianapolis, Miami and Phoenix—weathering increased demand for care from growing numbers of uninsured and Medicaid patients and fluctuations in public funding over the past 15 years. Generally, these public hospitals have adopted six key strategies to respond to growing capacity and financial pressures: establishing independent governance structures; securing predictable local funding sources; shoring up Medicaid revenues; increasing attention to revenue collection; attracting privately insured patients; and expanding access to community-based primary care. These strategies demonstrate how public hospitals often benefit from functioning somewhat independently from local government, while at the same time, relying heavily on policy decisions and funding from local, state and federal governments. While public hospitals appear poised for changes under national health reform, they will need to adapt to changing payment sources and reduced federal subsidies and compete for newly insured people. Moreover, public hospitals in states that do not expand Medicaid eligibility to most low-income people as envisioned under health reform will likely face significant demand from uninsured patients with less federal Medicaid funding.

![]() ublic hospitals in the United States have long provided general health care to low-income people and certain specialized services to the broader population. Public hospitals originated before the 20th century as almshouses—public and private charitable institutions that both housed and provided a range of health and other services for impoverished people, often over long periods of time. In contrast, wealthier people typically received medical care in their homes.

ublic hospitals in the United States have long provided general health care to low-income people and certain specialized services to the broader population. Public hospitals originated before the 20th century as almshouses—public and private charitable institutions that both housed and provided a range of health and other services for impoverished people, often over long periods of time. In contrast, wealthier people typically received medical care in their homes.

By the early 1900s, many of the private almshouses developed into businesses, focused on providing medical care to the emerging middle class able to pay for care. Public institutions also grew into larger, mainly medical facilities—often with federal funds from the 1946 Hill-Burton Act to expand hospital capacity—but many of their patients remained unable to pay for care.1

Signed into law in 1965, Medicaid covers many low-income and uninsured patients. However, Medicaid pays hospitals less than private insurers or Medicare, leaving public hospitals reliant on direct public funding and, to a lesser extent, philanthropy.

Over the past several decades, many local governments found owning and operating hospitals increasingly difficult as they faced rising costs of treating growing numbers of uninsured and Medicaid patients. While private hospitals nationally have posted margins near 5 percent over the past decade, public hospital margins have hovered at breakeven levels on average.2 Many public hospitals have closed or converted to private ownership. In 1999, one out of four hospitals was public, and by 2010, only one in five was public—often raising concerns that these changes would leave holes in the safety net and the health care delivery system more broadly.3

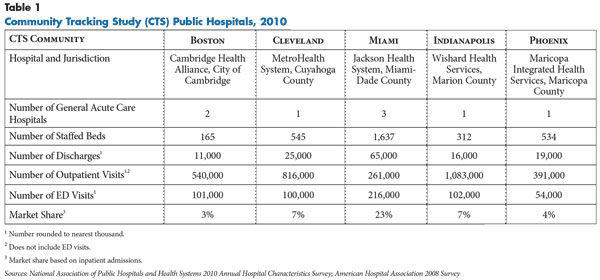

Five of the 12 Community Tracking Study (CTS) communities (see Data Source) have maintained a local public hospital that provides the bulk of safety net services in its community (see Table 1). The CTS has tracked these hospitals since 1996:

Along with inpatient hospital care, the five hospitals provide low-income patients with primary and specialty care through physicians who typically are employed or contracted through academic affiliations. They also accommodate language/cultural and social service needs prevalent among low-income populations. In addition to their safety net role, they are major providers of such services as trauma, burn and psychiatric care to the broader community. For example, CHA is the largest provider of inpatient mental health services in Massachusetts.

Not only have the five hospitals survived, they’ve grown over the last 15 years in response to growing demand for services and, in some cases, to preserve the provision of certain services in the community. Both CHA and Jackson added hospitals through mergers; Wishard, MIHS and MetroHealth remain single hospitals but have added inpatient capacity. Most expanded emergency department (ED) and outpatient services but still often struggle with inadequate capacity, resulting in long waits for appointments. With relatively few privately insured patients, these hospitals remain reliant on public funds to help cover their growing uncompensated care costs and Medicaid caseloads. They have faced chronic financial pressures and revenue changes, resulting in fluctuating bottom lines.

Fifteen years of tracking the five public hospitals highlight six strategies that have helped them adapt to challenging times. Although five hospitals is too small a sample to generalize to all public hospitals in the nation, other local public hospitals likely have experienced similar pressures and responded in related ways. The lessons learned by these five hospitals should prove useful to policy makers and other public hospitals, although each operates under different market conditions and levels of support. These five hospitals may be among the more resilient public hospitals, and an open question remains about whether these strategies will be sufficient for them to remain viable as they navigate changes under national health reform.

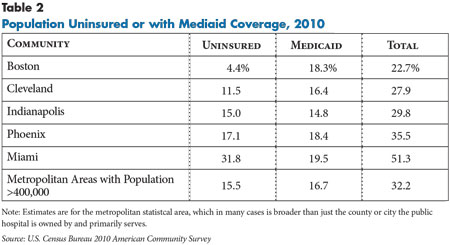

![]() he five public hospitals serve communities that vary in the level of potential need for safety net services—based on the percentage of the population that is uninsured or enrolled in Medicaid (see Table 2). Massachusetts has a very low rate of uninsurance but relatively high Medicaid enrollment, which is in part related to state reform efforts that helped many people obtain insurance, particularly public coverage. Phoenix and Miami have the greatest need, in terms of the percent of the population that is uninsured or covered by Medicaid.

he five public hospitals serve communities that vary in the level of potential need for safety net services—based on the percentage of the population that is uninsured or enrolled in Medicaid (see Table 2). Massachusetts has a very low rate of uninsurance but relatively high Medicaid enrollment, which is in part related to state reform efforts that helped many people obtain insurance, particularly public coverage. Phoenix and Miami have the greatest need, in terms of the percent of the population that is uninsured or covered by Medicaid.

Demands on local public hospitals also are affected by the extent to which other providers focus on caring for low-income people. Boston has the most extensive set of other safety net providers relative to need, including a large private safety net hospital—Boston Medical Center, which previously was public—serving greater Boston. CHA has a somewhat more distinct service area with its multiple hospital locations, including Cambridge, Somerville, Everett and the metro-north Boston area. Boston also has many community health centers (CHCs) including CHA’s hospital-licensed health centers; Miami, Phoenix, Indianapolis and Cleveland, respectively, have relatively less CHC capacity.4 Religiously affiliated private hospitals with missions to care for the poor also serve a secondary safety net role in these communities. In Miami, however, such hospitals typically serve more suburban areas, with Jackson the sole safety net hospital in the high-need center city.

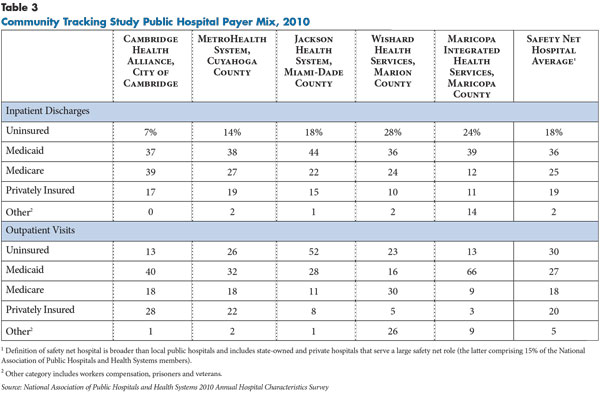

These factors affect the mix of patients the public hospitals serve (see Table 3). In 2010, Jackson and MIHS had a particularly challenging payer mix—in terms of the percentage of uninsured and Medicaid patients they treat across inpatient and outpatient settings—compared to Wishard, MetroHealth and CHA, which served relatively more privately insured and/or Medicare patients. Yet each hospital’s payer mix presents challenges, worsened in many cases by the fallout from the Great Recession and rising health care costs. Overall, public hospitals face different incentives than private hospitals that primarily treat better-paying privately insured patients. As one public hospital executive noted, “We don’t make more money by treating more patients; in fact, we could make less money by treating more patients.”

![]() orking with federal, state and local policy makers, public hospital executives across the five communities have adopted, to varying degrees and at different times, strategies to generate additional revenues and contain costs to keep the hospitals financially viable while sustaining their core services and mission to serve low-income people. These strategies include:

orking with federal, state and local policy makers, public hospital executives across the five communities have adopted, to varying degrees and at different times, strategies to generate additional revenues and contain costs to keep the hospitals financially viable while sustaining their core services and mission to serve low-income people. These strategies include:

Independent governance structure and management. Four of the five public hospitals now have a governance structure removed from local government but remain publicly owned. While direct public control might provide more short-term protection of staff and services, a more independent board can provide more flexibility in developing strategies and reducing costs in ways that may be unpopular with the community but could make the hospital more efficient and preserve ongoing viability. Independent governance structures have allowed public hospitals to retain or even increase access to public funds and helped separate strategic and operational decision making from the changing priorities and politics of local elected officials.

Public boards that are independent from local government have fewer constraints than hospitals under direct local control. The more independent hospitals typically face less political influence over labor decisions—for example, hiring, layoffs, benefits, salaries and raises—and fewer civil service rules and requirements, such as needing to hold meetings in public. Independent boards also have greater flexibility to attract board members with strong management experience in health care financing and delivery.5

Adoption of independent governance structures was usually linked to strategic decisions and/or financial challenges, making it difficult to study the effect of governance. For example, CHA’s public health authority, the Cambridge Public Health Commission, was established in the mid-1990s. CHA’s transition to a public authority and independent board allowed the public health department and the city-owned hospital to merge with a private community hospital to gain operational efficiencies and preserve access to health care services across a contiguous service area.6

Likewise, MIHS was struggling with significant deficits, and Maricopa County voters approved a hospital taxing district in 2003—the Maricopa County Special Health Care District—authorized to levy property taxes to help fund MIHS. The hospital is now managed by the district, led by an elected five-member board of directors. Although an elected board is not immune from individual political views and motivations, this new structure contributed to a steady increase in funding and improved management that helped the hospital’s financial performance.7

Jackson Health System has undergone fundamental change in its governance structure in recent years. Its governing body of almost 40 years, the 17-member Public Health Trust, was only nominally independent from the Miami-Dade Board of County Commissioners (BCC), which still retained authority over major operational decisions. In a key example, Jackson executives wanted to close the obstetrics unit at Jackson South Community Hospital because of a growing deficit and low patient volume, but the BCC prevented the closure, citing obstetrics as a core service for the public hospital to provide.8

In 2010, a county grand jury found that a lack of autonomy was a key factor in Jackson’s inability to remedy financial problems. As a result, the Trust was replaced with the seven-member Financial Recovery Board. This board reportedly operates independently from the local political environment and is more efficient in making management decisions in partnership with hospital executives. Indeed, the hospital reportedly is experiencing a turnaround through strategies to “right size” the organization and better match expenses to largely set revenues, including renegotiating labor contracts and cutting expenses. The hospital is expected to break even in fiscal year 2012.

Of the five hospitals, only MetroHealth remains directly operated by a local government—Cuyahoga County—with oversight from the county executive and county council. In response to the hospitals’ financial deficits in the mid-2000s, a new CEO and consultant-led management team was put in place. In addition to bringing specific expertise, as outsiders, consultants can help carry out cost-cutting measures that might be more difficult for hospital executives to implement alone under county control. Still, the cost-cutting decisions, which included significant job reductions, and spending on consultants were heavily scrutinized by county leaders as they determined the amount of the hospital’s annual subsidy.9 However, the changes reportedly have helped the hospital to operate in the black since 2009 and to invest in capital improvements.

Predictable and protected local funding source. Because they are owned by local governments, local public hospitals rely on a consistent local funding stream. However, the amount of local spending varies considerably and does not offer full support to care for the uninsured and other uncompensated costs. As one hospital CEO said, “Local property taxes are an important, but small, addition to our budget.” Annual local funding currently ranges from roughly $6 million for CHA to $330 million for Jackson, representing approximately 2 percent and 28 percent of total net revenues, respectively. Plus, CHA’s funding is predominantly intended to cover public health services since CHA operates the city’s health department.

Further, voters in all the communities except Cambridge approved financial support for their public hospitals by passing local initiatives. For example, Marion County/Indianapolis voters passed a bond referendum in 2009 to help build Wishard a replacement hospital—something otherwise challenging for a public hospital to finance given difficulties accessing capital.10

However, the structure of these initiatives can significantly affect the amount of funds they generate. While MIHS previously received sharply fluctuating annual county subsidies, the new property tax levy is structured so that it will not have a negative impact on revenues generated for the hospital and the total amount allocated to the hospital can increase to a certain extent. As a result, funding for MIHS has grown steadily from a base of $40 million in 2006 to $60 million currently. In contrast, Jackson’s revenues from a half-penny sales tax and a portion of property tax revenue are significant and rose when Miami’s tourist industry and housing market were robust. However, the fixed rates led to a revenue drop during the housing market crash and recession, with the amount stabilizing at about $333 million annually in recent years.

Further, these public hospitals provide enough charity care and benefit to the community to reduce pressure on nearby private hospitals; in turn, the private hospitals often support the public hospitals’ receipt of public funding, although the level of support can fluctuate. In a key example, other Miami hospitals over the years have vied for a portion of Jackson’s tax revenues to help with the costs they incur for treating uninsured patients. However, as Jackson’s financial health deteriorated in recent years, these providers backed off, acknowledging the huge safety net role Jackson plays and the ramifications—more uninsured patients at their doors—if Jackson were to close. Still, even if local funding amounts remain stable, they cover a smaller portion of public hospitals’ uncompensated care costs, which have been rising.

Medicaid and other federal funds. State and federal policy makers play a key role in allocating funds to public hospitals, primarily through a mix of interrelated funding streams from the Medicaid program. Overall, Medicaid is the largest single source of funds—35 percent of total net revenues—for safety net hospitals nationally. Medicaid inpatient discharges at the five hospitals are at or above the national average (36% of total discharges) for safety net hospitals. Because of their large Medicaid patient population, public hospitals are vulnerable to changes in Medicaid eligibility policies and payment rates, which are subject to state’s fluctuating budgets.

As states moved more Medicaid enrollees from traditional fee-for-service arrangements into managed care over the past 15 years, each of the five hospitals worried that health plan networks would include many private hospitals and that public hospitals’ Medicaid patients would choose or be assigned to other providers. However, this largely did not occur, in part because the public hospitals proactively prepared for managed care. All but MetroHealth started Medicaid managed care health plans, which helped retain and attract Medicaid patients, and some of the hospitals’ plans received favorable treatment from states in assignment of Medicaid enrollees and payment rates.

Also, federal/state supplemental payments through the Medicaid and Medicare programs are a major source of financial support for public hospitals (see box below for more information). However, among the five hospitals, Medicaid disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments declined in the last several years as funds were directed elsewhere to state health coverage programs, the state budget or to other providers. Medicaid DSH payments currently comprise less than 10 percent of total net revenues for most of the study hospitals, but 20 percent for Wishard. However, in some cases, public hospitals receive Medicaid DSH funds indirectly. For example, Massachusetts rolled its DSH funding into a Safety Net Care Pool to help support care for low-income people, from which CHA receives payments in lieu of a direct DSH allotment.

Many of the public hospitals, however, have benefited from new arrangements, including upper payment limit (UPL) provisions and/or Medicaid waivers. For example, after Arizona eliminated Medicaid coverage for childless adults in 2011 and reduced Medicaid payment rates by 15 percent over the last few years, MIHS faced significant operating losses and had little cash on hand. To provide some relief, last year the hospital worked with the state to create a Safety Net Care Pool. Under the arrangement, MIHS transfers the value of the care it provided to Medicaid and uninsured patients to the state, which in turn used it as matching funds to obtain $50 million in federal Medicaid supplemental funds for the hospital. Still, MIHS’ margin has fallen by half to approximately 2 percent since the state cut the Medicaid program.

Indeed, the various Medicaid funding streams are interwoven, with gains or losses from one source affecting funding from another source. For example, in 2012, Indiana started a Hospital Assessment Fee program that taxes a broad set of providers and redistributes the funds plus federal matching funds to safety net hospitals, including Wishard. Because these new payments will reduce Wishard’s Medicaid payment shortfall, the hospital’s DSH allocation will decline to some degree.

Paying attention to revenue collection efforts. Over the last 15 years, public hospitals have become more assertive and systematic about collecting payment for services. They have redoubled efforts to help uninsured patients enroll in public insurance when eligible and to collect payment from third-party payers and patients—patient cost sharing from insured people and fees that the uninsured pay on a sliding scale according to income.

For example, facing financial deficits several years ago, Wishard instituted discounts for uninsured patients who paid on time and added a fee for emergency department visits to encourage uninsured patients to seek primary care over hospital care. With the help of new information technology, MIHS streamlined the process for determining which uninsured patients are eligible for free or reduced cost care and implemented a more proactive billing strategy to pursue payment from others.

While public hospitals reportedly have tried to strike a balance between collecting from the patients who can pay something and also not turning away, or harassing, those who cannot, financial constraints have led some public hospitals to limit the patients they serve. For instance, while expanding charity care discounts to county residents, MetroHealth instituted a $150 fee for patients who live outside the county to see a MetroHealth physician.

Attracting privately insured patients. To further boost revenues, some public hospitals have attempted to attract higher-income or privately insured patients while maintaining their mission to focus on low-income people. Privately insured patients make up less than 20 percent of inpatient discharges across the five hospitals. However, payer mix varies more among hospital outpatient visits, with the percentage of privately insured patients in the single digits for Wishard, MIHS and Jackson but almost a quarter at CHA and MetroHealth, which may be linked to the socioeconomic profile of the neighborhoods where these facilities are located. Having a small percentage of insured patients often limits a public hospital’s ability to negotiate higher payment rates from commercial insurers in the way that private hospitals with larger volumes and market clout can. For example, recent health care cost transparency reports by the state of Massachusetts revealed that certain safety net hospitals, including CHA, receive significantly lower payment rates compared to other hospitals.15

To attract privately insured patients, the five public hospitals have worked to demonstrate improved efficiency and quality of care. Such changes can make public hospitals more attractive to commercial health plans as they contract with hospitals to form provider networks. Wishard and CHA have had some success in attracting privately insured patients through facility improvements. For example, CHA’s nationally recognized emergency department transformation has reduced average wait times to less than 5 minutes, while improving clinical care and connecting patients to primary care. Likewise, Wishard’s maternity and physical therapy facilities and cardiac catheterization lab attract patients across income levels and payer types.

Also, all five hospitals now have medical school affiliations, which not only help provide low-income patients with access to physician services, but also can signal the availability of renowned physicians and the latest technology. Most recently, MIHS completed affiliating with a medical school after four years of negotiations and achieving quality improvements.16 Jackson’s affiliation with the prestigious University of Miami faculty practice (UHealth) has helped it attract privately insured patients, although Jackson reportedly lost some private patients to a nearby hospital that UHealth acquired. Jackson has recently announced plans to add trauma care to both its North and South campuses—services that are expected to bring more privately insured patients, given these hospitals’ locations in more suburban areas.17

Expanding primary care in the community. While remaining key providers of medical and surgical specialty care for low-income people, the five public hospitals have improved access to primary care services over the last 15 years, with an emphasis on placing clinics in neighborhoods where low-income people live. The key goals are to help improve low-income people’s access to timely care to prevent them from developing more serious health problems and to reduce their use of emergency and inpatient care. This strategy helps public hospitals reduce financial losses from treating uninsured patients. However, the financial benefit of this strategy with Medicaid patients is less clear because Medicaid payment for primary care services typically covers less of hospitals’ costs than payment for hospital services.

The hospitals increasingly are looking for ways to generate more Medicaid and other revenues for primary care services. In a key example, MIHS obtained federally qualified health center (FQHC) look-alike status for its 11 clinics in 2006 to secure higher Medicaid payments.18 MIHS created a separate governing council to oversee the clinics to meet the federal requirement that more than half of an FQHC’s board must consist of health center patients. Wishard also has applied for FQHC status with a similar type of governing board.

In fact, Wishard is expanding primary care on several fronts. The hospital more than doubled its number of community clinics—from six in 2002 to 13 by 2010—and is currently building another primary care center in a very low-income area that will be twice as large as its current largest center. Paying for housing for homeless patients and providing primary and other care in those facilities has saved the system money by reducing the use of emergency and other hospital services by the uninsured. As Wishard expands and moves more outpatient services into the community, its new hospital facility scheduled to open in 2013 will occupy a third less square footage. Also, the system has a program that provides incentives for uninsured patients to seek primary and preventive services, and its longstanding electronic health record system helps coordinate care and use resources more efficiently. To further improve care coordination, the hospital recently formed an exclusive affiliation with its primary care physicians, and these physicians eventually will become hospital employees.

MetroHealth is expanding primary care to reach both more low-income people and attract more privately insured patients. With more than a dozen clinics spread throughout the metro area, the hospital system is adding four clinics to the outer suburban ring of Cleveland, an area with more privately insured patients than the downtown area. As another way to attract patients, these clinics also will include more specialty services on site.

With the acquisition of two hospitals over the past 15 years to expand its general footprint and attract more privately insured patients, Jackson appears to be more focused on expanding inpatient capacity than adding primary care capacity. In fact, Jackson provides relatively few non-ED outpatient visits relative to the overall size of the system. However, in the past 18 months, the hospital system has added some primary care services in the county and improved capacity at its main campus clinic through use of non-physician clinicians.

Public hospitals also view building primary care capacity as a foundation to their preparations for national health reform. More primary care capacity likely will be needed to serve more insured people and for evolving payment mechanisms, such as global payments or shared-savings arrangements, which will leave providers with greater financial and clinical responsibility for panels of patients.

Medicaid and Medicare Supplemental PaymentsIn addition to fee-for-service payments for treating Medicaid patients, public hospitals—and certain private hospitals—that care for many low-income and uninsured people receive supplemental federal funding from Medicaid and Medicare known as disproportionate share hospital, or DSH, payments. The federal government provides each state a Medicaid DSH allotment; these amounts vary widely in total and on a per capita Medicaid enrollee and uninsured person basis, which is related in part to a state’s historical DSH spending.11 Beyond the minimum requirement to allocate Medicaid DSH payments to hospitals that provide a certain level of inpatient services to Medicaid or low-income patients according to a formula, states have significant latitude in how they distribute Medicaid DSH funds.12 Also, an individual hospital cannot receive DSH funding in excess of its unreimbursed costs of treating Medicaid and uninsured patients. A smaller source of funding support for public hospitals, Medicare DSH payments are distributed directly to hospitals that treat many low-income patients as an adjustment to their Medicare inpatient payments. On top of DSH payments, many public hospitals receive additional supplemental Medicaid payments up to the so-called upper payment limit, or UPL. The UPL is defined as a reasonable estimate of the amount that Medicaid-covered services would be paid for under Medicare—payment rates that typically are considerably higher than state Medicaid payment rates. In some cases, state Medicaid waivers—in which the federal government allows a state to modify how Medicaid services are financed and delivered to improve patient care and generate cost savings for the program as a whole—generate additional types of supplemental payments and/or distribute DSH and UPL dollars in new ways. Over the years, states have been creative in tapping funding sources other than state revenues to match federal Medicaid funding.13 These sources often include local spending on health care and fees on health care providers. Some states have used additional federal matching funds to supplant or supplement state Medicaid funding or, in some instances, diverted additional funding to non-health care purposes. As a result, federal policy makers have repeatedly increased oversight of the states’ use of supplemental Medicaid funding. Recent discussions about reducing the federal deficit have placed provider taxes under increased scrutiny.14 |

![]() he Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act is expected to impact public hospital finances in two opposing ways: 1) an improved payer mix as lower-income, uninsured people gain Medicaid or subsidized private insurance coverage; and 2) threats to federal Medicaid and Medicare DSH payments. However, several state and community factors will affect the relative size of each change and, therefore, the net financial impact. As one hospital executive said, “As far as the dollars and cents, it [reform] is an equation that isn’t filled in yet.” Public hospitals can gain some insight from Massachusetts’ experience with health reform, which significantly expanded health coverage but resulted in funding changes that negatively affected CHA’s and other safety net providers’ finances.

he Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act is expected to impact public hospital finances in two opposing ways: 1) an improved payer mix as lower-income, uninsured people gain Medicaid or subsidized private insurance coverage; and 2) threats to federal Medicaid and Medicare DSH payments. However, several state and community factors will affect the relative size of each change and, therefore, the net financial impact. As one hospital executive said, “As far as the dollars and cents, it [reform] is an equation that isn’t filled in yet.” Public hospitals can gain some insight from Massachusetts’ experience with health reform, which significantly expanded health coverage but resulted in funding changes that negatively affected CHA’s and other safety net providers’ finances.

Gaining insured patients. Public hospitals expect to treat more insured patients—both as their existing uninsured patients become insured and from newly insured people using more services because they have insurance. Given their low incomes, the core patients served by public hospitals are largely expected to gain Medicaid coverage over private coverage. Public hospitals in communities with relatively high rates of uninsurance—for example, Miami and Phoenix—could experience the largest improvements in payer mix.

However, the effect will be muted depending on how many of the uninsured in a community actually enroll in insurance programs, which will be affected by several factors, including how many are eligible for Medicaid and subsidized private coverage and the affordability of those options. Recent immigrants will be ineligible for Medicaid—either because they are undocumented or have not been in the country at least five years, although the latter group will be eligible for private subsidized coverage. For instance, one estimate suggests that one-third of Jackson’s uninsured patients will remain uninsured.

A major concern for the public hospitals, which dates from the June 2012 U.S. Supreme Court decision on the health reform law, is the financial impact if their states choose not to expand Medicaid eligibility to almost all people with incomes below 138 percent of the federal poverty level. Indeed, Florida, Arizona, Indiana and Ohio all have Republican governors who have voiced opposition to the health reform law, especially the Medicaid expansion.

Even if states technically agree to an expansion, they might devote relatively few resources to getting people enrolled compared to other states. In such cases, local outreach efforts and public hospitals’ established strategies for helping to identify and enroll patients in Medicaid will be especially important. In fact, in a move typically spearheaded at the state level, MetroHealth has applied for a federal waiver to start covering almost half of the uninsured people who could become eligible for Medicaid in 2014, using a local $36-million annual subsidy to secure federal matching funds.19

If their state’s Medicaid eligibility does expand, public hospital executives typically expected to experience some, albeit limited, competition from other hospitals for newly insured patients. Most of this competition is expected to come from hospitals already serving a safety net role in the community, such as religiously affiliated private hospitals. Because the health reform law does not raise Medicaid hospital payment rates or provide other incentives to serve more Medicaid patients, perhaps many private hospitals would not aggressively seek to serve these patients. And, if past experience holds, the fact that most of the public hospitals own Medicaid health plans “allows them to be a player in that market and is a strategy that mitigates some of the risk [of losing Medicaid patients to other hospitals],” according to a public hospital executive. However, recent growing interest of private-equity investors and for-profit health care companies in acquiring safety net hospitals in some communities may signal increased competitive threats for public hospitals.20

Lower-income people gaining subsidized private insurance are less on the radar screen of public hospital executives than those gaining Medicaid coverage. To the extent that this population is served by private insurers through the health insurance exchanges (rather than a state choosing to implement a public Basic Health Plan option), this population may be largely served by private hospitals. Still, public hospitals want to be included in provider networks, especially to provide ongoing care to patients they already serve. Public hospitals’ expertise in providing support services that low-income people need, such as transportation, language interpreters and social services, may attract many of the newly insured low-income population. Public hospitals could still face significant uncompensated care costs if patients gain private coverage that requires significant cost sharing, such as high deductibles, that they cannot afford to pay.

The hospital executives expected slightly more competition for primary care services as Medicaid payment rates increase to Medicare levels in 2013 and 2014. It appears these rate increases also apply to primary care services provided in a hospital setting.21 This increase could prove a threat to public hospitals if private hospitals and physicians decide the increase—which could be significant in states where current Medicaid payment rates are very low relative to Medicare rates—is sufficient to pursue more Medicaid patients. However, the common perception across communities is that primary care capacity is inadequate currently, so there will be plenty of patients to go around. Still, competition for Medicaid patients from FQHCs could heat up as they continue to expand capacity and focus on Medicaid patients and possibly those with subsidized private coverage.22

Reduced subsidies. Public hospital executives were more concerned about eroding subsidies than about losing patients. Under the health reform law, overall Medicaid DSH payments will decline gradually between 2014 and 2020, to 50 percent of current levels. While these planned cuts are based on the assumption that more people will be insured and generate revenues for hospitals, public hospitals could still be treating many uninsured patients.

Federal guidance is pending on the implementation of the Medicaid DSH cuts. The health reform law directs the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to develop a methodology that would impose the largest reductions in DSH allotments on states that have the lowest percentages of uninsured individuals or do not target their DSH payments to hospitals with high levels of uncompensated care and Medicaid patients. The law also requires redistribution of DSH funding to take into account the states with historically low levels of DSH funds and those that have used former DSH allotments for coverage waivers, such as Massachusetts. Public hospitals also are calling for policy makers to revisit these cuts in the context of the Supreme Court ruling that states can opt out of the Medicaid expansions, which would leave more people uninsured than initially expected.

Cuts to Medicare DSH funding also are on the horizon. Medicare DSH payments will decline by 75 percent over 10 years beginning in 2014 and then be adjusted for an individual hospital based on the percentage of the population that remains uninsured in the hospital’s state and the amount of uncompensated care the hospital provides.

Public hospitals receiving extra funding through Medicaid waivers expressed some uncertainty about the terms of future Medicaid waiver renewals under national reform. Likewise, there is uncertainty about the future of provider taxes that generate supplemental funding for many public hospitals.

Public hospital executives also were unsure about the future of local funding streams. As the number of uninsured people declines and policy makers and the electorate perceive that access problems have been remedied, communities might reduce funding to public hospitals, particularly if budgets remain tight. A greater proportion of the remaining uninsured will be undocumented immigrants, and there may be less public support to care for these patients. For instance, MIHS is seven years into a 20-year lifespan for its property tax revenues, but residents could mount a referendum to repeal the district’s taxing authority earlier. Certainly the loss of local funds is a bigger concern for hospitals like Jackson where local funding comprises a relatively larger portion of their revenues than hospitals with more diversified funding.

Lessons from Massachusetts. Because Massachusetts’ reform law is structurally similar to national reform, CHA’s early experience and challenges with state reform may preview how other public hospitals will fare under national reform. Although CHA’s payer mix shifted significantly to Medicaid and patients with subsidized coverage under a Medicaid waiver (Commonwealth Care), CHA’s aggregate payment for these patients declined from pre-reform levels received from the state for Medicaid and uninsured patients. CHA lost subsidies as the state redirected much of the hospital funding from its uncompensated care pool to subsidize coverage. Also, facing budget shortfalls, the state cut Medicaid inpatient payment rates to CHA by 25 percent several years ago and outpatient rates by 10 percent each of the last two years. The hospital system has responded through a reconfiguration plan that, for example, reduced staff, downsized inpatient services by moving from three to two inpatient facilities, merged some primary care sites, and reduced behavioral health services to focus more on the hospital system’s immediate service area. However, the hospital continues to post negative operating margins.

National reform will bring additional changes for CHA. While CHA may receive more funding when the state receives increased funding for Medicaid enrollees who previously gained coverage under state-led expansions, CHA faces further challenges related to DSH cuts under health reform and other payment changes.

![]() ooking ahead to reform, public hospital executives across the five communities acknowledged that ensuring their hospitals are attractive to insured patients will be an important factor in maintaining financial viability. For example, to become so-called destination hospitals, both MIHS and MetroHealth plan to replace and update their aging facilities, although the recession has delayed MIHS’ plans by about 10 years. Public hospital executives also stressed the need to continue reducing costs and improving operations.

ooking ahead to reform, public hospital executives across the five communities acknowledged that ensuring their hospitals are attractive to insured patients will be an important factor in maintaining financial viability. For example, to become so-called destination hospitals, both MIHS and MetroHealth plan to replace and update their aging facilities, although the recession has delayed MIHS’ plans by about 10 years. Public hospital executives also stressed the need to continue reducing costs and improving operations.

In particular, public hospital executives stressed the importance of continuing to revamp care delivery to align with reform’s emphasis on shifting to primary and preventive care over costlier specialty and hospital care. Namely, they are engaging in patient-centered medical home (PCMH) efforts to improve coordination of care. MIHS’ health centers have achieved National Committee on Quality Assurance (NCQA) Level 3 PCMH certification, which not only brings the system more revenue but also reportedly “perks up” the ears of commercial insurers seeking primary care providers that can demonstrate strong clinical outcomes. CHA also is implementing the PCMH model of care, with several primary care sites achieving NCQA Level 3 recognition and others in the process.

Further, with their wide range of services, employed physicians and Medicaid health plans, many public hospitals already have major components to become part of accountable care organizations (ACOs). Yet most of the five hospitals are not yet participating in ACOs.

CHA is the exception. The hospital is participating in an ACO using a risk-based global payment model for enrolled Medicaid and Commonwealth Care patients.23 Further, CHA recently announced a potential clinical affiliation with Harvard-affiliated Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital, which may be a step toward an ACO-like arrangement. Beth Israel’s strong financial performance and tertiary services (which CHA does not provide) could help CHA, while Beth Israel may benefit from CHA’s lower cost structure as a community hospital and its large primary care network with 15 primary care centers and employed physicians.24 Indeed, CHA and other Massachusetts hospitals are under additional pressure to contain costs as the state implements a law that caps health care spending growth on a statewide basis.

![]() s 2014 nears, policy attention increasingly will focus on outreach and enrollment efforts to move uninsured people into Medicaid or subsidized private coverage. However, for low-income people especially, coverage does not guarantee access to appropriate and timely health care. As in past coverage expansions, the role of public hospitals and other safety net providers will not disappear and ultimately could grow as more low-income people secure coverage and seek care. Policy makers will want to consider ways to ensure adequate access to primary care, specialty care, inpatient care, mental health services, highly specialized services—trauma, burn and transplants—as well as non-medical support services. For many states and communities, this may mean ensuring the viability of local public hospitals.

s 2014 nears, policy attention increasingly will focus on outreach and enrollment efforts to move uninsured people into Medicaid or subsidized private coverage. However, for low-income people especially, coverage does not guarantee access to appropriate and timely health care. As in past coverage expansions, the role of public hospitals and other safety net providers will not disappear and ultimately could grow as more low-income people secure coverage and seek care. Policy makers will want to consider ways to ensure adequate access to primary care, specialty care, inpatient care, mental health services, highly specialized services—trauma, burn and transplants—as well as non-medical support services. For many states and communities, this may mean ensuring the viability of local public hospitals.

Indeed, while many public hospitals have matured into large, relatively independent businesses, they remain heavily reliant on policy decisions and funding at all levels of government. Also, the particular pressures that local public hospitals face and how well they respond vary by community. On the one hand, the five hospitals studied have demonstrated resilience over time. In many ways, they seem well positioned to adapt and thrive under health reform. Yet, four of these hospitals are in states where a key piece of reform—Medicaid coverage expansions—may not occur. If so, the hospitals’ federal funding could plummet while the costs of caring for low-income people continue, raising the potential for significant financial shortfalls.

And, as seen in Massachusetts, even public hospitals in states supportive of reform could struggle if new revenue from Medicaid and other insured patients minus the loss of subsidies does not approximate their costs of providing care. While public hospitals will need to continue improving care delivery to increase quality and efficiency, they also almost certainly will need external funding as long as they care for large numbers of uninsured and Medicaid patients.

| 1. | Starr, Paul, The Social Transformation of American Medicine: The Rise of a Sovereign Profession and the Making of a Vast Industry, Basic Books, New York, N.Y. (1984). |

| 2. | American Hospital Association (AHA), Trendwatch Chartbook 2011, Washington, D.C. (2011); and National Association of Public Hospitals (NAPH), Study Reveals NAPH Members are ‘Providers of Choice’ for All Patients, Research Brief, Washington, D.C. (May 2011). NAPH membership extends beyond local public hospitals and includes state-owned and private hospitals that serve a large safety net role (the latter comprising 15% of NAPH members). |

| 3. | Stolberg, Sheryl G., “After Two Centuries, Washington is Losing Its Only Public Hospital,” The New York Times (May 7, 2001); AHA, Fast Facts on U.S. Hospitals, Chicago, Ill. (Jan. 3, 2012); and Legnini, Mark W., et al., Privatization of Public Hospitals, Kaiser Family Foundation, Menlo Park, Calif. (January 1999). |

| 4. | Katz, Aaron B., et al., A Long and Winding Road: Federally Qualified Health Centers, Community Variation and Prospects Under Reform, Research Brief No. 21, Center for Studying Health System Change, Washington, D.C. (November 2011). |

| 5. | Gage, Larry S., Anne B. Camper and Robert Falk, Legal Structure and Governance of Public Hospitals and Health Systems, NAPH, Washington, D.C. (August 2006). |

| 6. | Brennan, Niall, Stuart Guterman and Stephen Zuckerman, The Health Care Safety Net: An Overview of Hospitals in Five Markets, Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Washington D.C. (April 2001). |

| 7. | Ernst & Young, Financial Statements: Maricopa County Special Health Care District, Report of Independent Auditors Years Ended June 30, 2011 and 2010, Phoenix, Ariz. (Jan. 25, 2012). |

| 8. | Brannigan, Martha, “County Reverses Jackson’s Plans to Close its OB Unit,” The Miami Herald (July 8, 2010). |

| 9. | Tribble, Sarah Jane, “Cuyahoga County Council Intensifies Questioning of MetroHealth System,” The Plain Dealer (Oct. 15, 2011). |

| 10. | In honor of a local couple who provided $40 million for the new facility, the entire Wishard system will be renamed Eskenazi Health when the new hospital is complete in 2013. |

| 11. | McKethan, Aaron, et al., “Reforming the Medicaid Disproportionate-Share Hospital Program,” Health Affairs, Vol. 28, No. 5 (September/October 2009). |

| 12. | Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), “Medicaid Program; Final FY 2009 and Preliminary FY 2011 Disproportionate Share Hospital Allotments,” Federal Register, Vol. 76, No. 1 (Jan. 3, 2011). |

| 13. | Coughlin, Teresa A., Brian K. Bruen and Jennifer King, “States Use of Medicaid UPL and DSH Financing Mechanisms,” Health Affairs, Vol. 23, No. 2 (March 2004). |

| 14. | Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Medicaid Financing Issues: Provider Taxes, Washington, D.C. (May 2011). |

| 15. | Massachusetts Center for Health Information and Analysis, Provider Price Variation in the Massachusetts Commercial Market—Baseline Report, Boston, Mass. (November 2012). |

| 16. | Lee, Michelle Ye Hee, and J. J. Hensley, “Maricopa Agency for Inmate Care Regains Credentials,” The Arizona Republic (April 7, 2012). |

| 17. | Dorschner, John, “Jackson Health System Board Approves Two New Trauma Centers,” The Miami Herald (Feb. 27, 2012). |

| 18. | FQHCs and FQHC look-alikes receive prospective payment system Medicaid rates, which are typically higher than a state’s traditional primary care physician payment. The rates are all-inclusive to cover the services provided within a single encounter and are based on the FQHC’s historical costs and updated annually. |

| 19. | Tribble, Sarah Jane, “MetroHealth Wants to Create Medicaid Subsidy Program for Uninsured,” The Plain Dealer (March 11, 2012). |

| 20. | Gage, Larry S., Transformational Governance: Best Practices for Public and Non Profit Hospitals and Health Systems, American Hospital Association’s Center for Healthcare Governance, Chicago, Ill. (2012). |

| 21. | CMS, “Payments for Services Furnished by Certain Primary Care Physicians and Charges for Vaccine Administration Under the Vaccines for Children Program,” Federal Register, Vol. 77, No. 92 (May 11, 2012). |

| 22. | Katz, et al. (2011). |

| 23. | Daly, Rich, “Sincerest Form of Flattery: Mimicking Medicare, States Want to Try Accountable Care Models for Medicaid,” Modern Healthcare (Jan. 9, 2012). |

| 24. | Donnelly, Julie M., “Beth Israel and Cambridge Health Alliance Eye Affiliation,” Boston Business Journal (Oct. 9, 2012). |

Since 1996, HSC has conducted site visits to 12 nationally representative metropolitan communities every two to three years as part of the Community Tracking Study (CTS) to interview health care leaders about the local health care market and how it has changed. The communities are Boston; Cleveland; Greenville, S.C.; Indianapolis; Lansing, Mich.; Little Rock, Ark.; Miami; northern New Jersey; Orange County, Calif.; Phoenix; Seattle; and Syracuse, N.Y. During the seventh round of site visits, almost 550 interviews were conducted in the 12 communities between March and October 2010. This Research Brief focuses on five communities that own and operate local public hospitals—Boston, Cleveland, Indianapolis, Miami and Phoenix. While many of the other communities have state university-run public hospitals, they are outside the focus of this analysis because their safety net roles vary and their operations are less affected by policies, decision making and funding at the local level. In communities without any sort of public hospital—for example, Lansing and Greenville—to some degree certain private hospitals play a safety net role. This study analyzed findings from the seven rounds of CTS site visits, especially drawing from the 177 interviews conducted in 2010 with leaders of public hospitals and other safety net hospitals, community health centers, state and local health agencies, consumer advocates, and others with knowledge of the health care safety net for low-income people. Follow-up interviews conducted in October 2012, media reports and other studies provided additional information on more recent developments.

The 2010 Community Tracking Study site visits and resulting publications were funded jointly by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the National Institute for Health Care Reform.