HSC Research Brief No. 26

July 2013

Tracy Yee, Amanda E. Lechner, Ellyn R. Boukus

As the U.S. health care system grapples with strained hospital emergency department (ED) capacity in some areas, primary care clinician shortages and rising health care costs, urgent care centers have emerged as an alternative care setting that may help improve access and contain costs. Growing to 9,000 locations in recent years, urgent care centers provide walk-in care for illnesses and injuries that need immediate attention but don’t rise to the level of an emergency. Though their impact on overall health care access and costs remains unclear, hospitals and health plans are optimistic about the potential of urgent care centers to improve access and reduce ED visits, according to a new qualitative study by the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC) for the National Institute for Health Care Reform.

Across the six communities studied—Detroit; Jacksonville, Fla.; Minneapolis; Phoenix; Raleigh-Durham, N.C.; and San Francisco—respondents indicated that growth of urgent care centers is driven heavily by consumer demand for convenient access to care. At the same time, hospitals view urgent care centers as a way to gain patients, while health plans see opportunities to contain costs by steering patients away from costly emergency department visits. Although some providers believe urgent care centers disrupt coordination and continuity of care, others believe these concerns may be overstated, given urgent care’s focus on episodic and simple conditions rather than chronic and complex cases. Looking ahead, health coverage expansions under national health reform may lead to greater capacity strains on both primary and emergency care, spurring even more growth of urgent care centers.

![]() ver the last two decades, urgent care centers (UCCs) have proliferated, growing to 9,000 facilities in the United States.1 The recent, rapid expansion of urgent care centers is often attributed to such factors as long wait times for primary care appointments, crowded emergency departments and patient demand for more accessible care, including after-hours appointments.

ver the last two decades, urgent care centers (UCCs) have proliferated, growing to 9,000 facilities in the United States.1 The recent, rapid expansion of urgent care centers is often attributed to such factors as long wait times for primary care appointments, crowded emergency departments and patient demand for more accessible care, including after-hours appointments.

Urgent care centers provide care on a walk-in basis, typically during regular business hours, as well as evenings and weekends, though not 24 hours a day. UCCs commonly treat conditions seen in primary care practices and retail clinics, including ear infections, strep throat and the flu, as well some minor injuries, such as lacerations and simple fractures. In contrast to emergency departments, UCCs generally are not equipped to deal with trauma, provide resuscitation or admit patients to a hospital—all reasons for seeking ED care. UCCs are typically staffed by physicians, generally with backgrounds in primary care or emergency medicine, and some also have nurse practitioners or physician assistants working under physician supervision.

Urgent care centers first emerged in the 1980s but did not take root, in part, because the industry lacked a sufficient marketing strategy to draw consumer interest.2 Since then, patient demand for more convenient access to care reportedly has increased, prompting renewed growth in urgent care centers. Indeed, according to a recent study, approximately 60 percent of patients with a usual primary care physician (PCP) reported that their PCP practices do not offer extended hours, suggesting a niche for urgent care centers to fill.3

Historically, urgent care centers often were independently owned, standalone facilities, but the landscape of urgent care centers has changed considerably. Large urgent care center chains operate in some regions. Also, hospital systems are establishing UCCs to expand their service area and referral base. More recently, health insurers are partnering with or establishing UCCs as a way to control spending growth by shifting some care from emergency departments to lower-cost UCCs. Urgent care center visits generally cost less than emergency department visits, though they tend to be on par with primary care office visits.4

This Research Brief examines the growth of urgent care centers across six communities—Detroit; Jacksonville, Fla.; Minneapolis; Phoenix; Raleigh-Durham, N.C.; and San Francisco—to study the impact of urgent care centers on local delivery systems, with a focus on access, coordination and overall costs of care. The six communities were selected for their high penetration of urgent care centers and represent varying levels of provider integration, a factor that may influence the role of urgent care centers in expanding access to care as well as the degree to which they may disrupt continuity of care (see Data Source).

![]() rgent care centers in the study sites tend to be located in more populous, higher-income areas. Urgent care industry respondents stated that they typically target locations that attract a lot of vehicle or foot traffic and that are visible from major roads. They also tend to place UCCs in more-affluent areas, particularly in suburbs with a concentration of people with employer-sponsored coverage, a young population or rapid population growth. “Urgent care is a volume-driven model, so a certain population density must be present for the UCC to capture sufficient volume to breakeven. That’s a big reason you see UCCs in the suburbs of larger metro areas,” one urgent care chain executive said.

rgent care centers in the study sites tend to be located in more populous, higher-income areas. Urgent care industry respondents stated that they typically target locations that attract a lot of vehicle or foot traffic and that are visible from major roads. They also tend to place UCCs in more-affluent areas, particularly in suburbs with a concentration of people with employer-sponsored coverage, a young population or rapid population growth. “Urgent care is a volume-driven model, so a certain population density must be present for the UCC to capture sufficient volume to breakeven. That’s a big reason you see UCCs in the suburbs of larger metro areas,” one urgent care chain executive said.

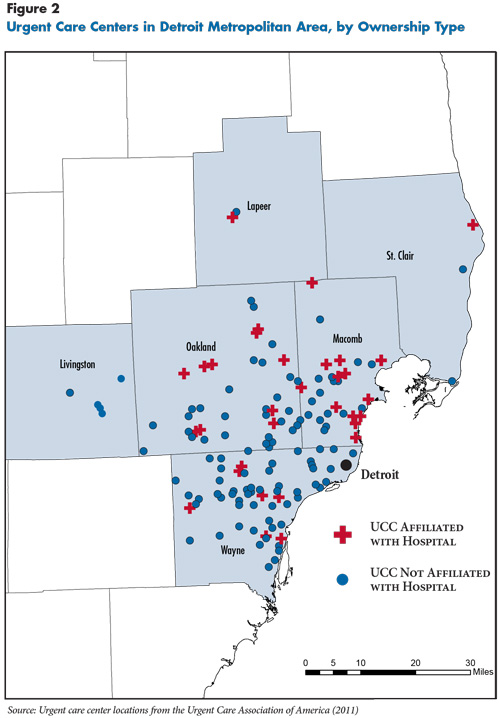

According to national survey data from the Urgent Care Association of America (UCAOA), in 2012, 35 percent of UCCs were owned by physicians or physician groups, 30 percent by corporations, and 25 percent by hospitals. Another 7 percent were owned by non-physician individuals or franchisors. However, the breakdown of ownership varies across communities. For example, nearly four out of five UCCs in Minneapolis are owned by or affiliated with hospitals, according to UCAOA data, compared with one in four in Detroit (see Figure 1 and Figure 2). In general, Minneapolis, San Francisco, Jacksonville and Raleigh-Durham have a relatively higher share of hospital-owned or affiliated UCCs, while Detroit and Phoenix have more independently owned UCCs (including chains).

The relatively high rates of hospital-owned or affiliated UCCs in Minneapolis, San Francisco, Raleigh-Durham and Jacksonville may reflect the greater presence of integrated delivery systems in the markets. For example, in Minneapolis and San Francisco, a few prominent health systems have established urgent care centers to expand their service sites. Similarly, in Raleigh-Durham, some major health systems have partnered with or acquired urgent care centers. Jacksonville has a high prevalence of hospital-affiliated UCCs largely because of a partnership between Solantic/CareSpot—a large urgent care chain—and Baptist Health, a large hospital system. Hospital respondents in these markets viewed urgent care centers as a way to retain current patients and gain new ones by providing additional, more convenient access. According to a San Francisco health system executive, urgent care is “viewed as a funnel into our integrated health system. It’s a way to get a referral to [one of our affiliated providers]. It’s a gateway.”

By comparison, more fragmented provider markets—those with more competing hospitals and health systems and a larger proportion of physicians in independent practices, such as Detroit and Phoenix—tend to have greater penetration of independently owned urgent care centers. The lack of dominant hospital systems or physician groups in these markets relative to the other markets may allow smaller, independent UCCs to enter and compete more effectively. Respondents in Detroit and Phoenix reported that urgent care centers commonly provide ancillary services, such as travel and occupational medicine, as a way to draw more patients.

![]() verall, respondents perceived that urgent care centers improve access to certain services for privately insured people without significantly disrupting care continuity. But respondents were uncertain about UCCs’ impact on costs.

verall, respondents perceived that urgent care centers improve access to certain services for privately insured people without significantly disrupting care continuity. But respondents were uncertain about UCCs’ impact on costs.

Access to care. Urgent care centers fill an access gap by providing walk-in care, especially during evening and weekend hours, for patients without a primary care physician or those unable to schedule a timely PCP appointment. While urgent care centers don’t increase the overall number of primary care clinicians because they draw from the existing supply of PCPs, they may improve access to primary care services by offering more convenient availability, especially during evenings and weekends, when primary care offices are typically closed.

UCCs primarily serve privately insured and Medicare patients. Across the study sites, UCC respondents reported contracting with many private insurers that cover urgent care visits with patient copayments ranging from $30 to $60. Health plans reported a recent trend of making urgent care copayments lower than ED visit copayments, higher than primary care visits and similar to specialist physician visit copayments.

Unlike hospital emergency departments, UCCs typically are not subject to the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA), a federal law that requires hospitals to screen patients and provide emergency services regardless of an individual’s ability to pay. In rare cases, a UCC operating under a hospital’s license is subject to EMTALA. Across the study sites, UCCs tend not to participate in Medicaid, reportedly because of low payment rates. Of the six communities studied, only Phoenix appeared to have significant contracting between Medicaid health plans and UCCs. This may be a result of health plans requiring providers to accept Medicaid managed care patients if providers want contracts to care for commercial patients, along with Arizona’s relatively high Medicaid payment rates.

UCCs do serve some uninsured patients but typically require upfront payment, which can be a barrier for low-income patients. To ensure that they receive payment and to promote their centers, many UCC respondents reported offering discounted or flat fees to patients who pay in full at the time of treatment rather than in installments. Other UCCs offer membership programs where subsequent visits are discounted. According to a respondent at an independent Phoenix urgent care center, “[The membership card] is $5 more than you would pay for one visit. Any time you come back within a year, you would get a reduced rate [for the visit].” Such discounts and memberships reportedly were popular among uninsured people who could afford to pay out of pocket for care.

Care coordination. Most respondents perceived that urgent care centers do not significantly disrupt existing relationships with primary care providers or coordination of patient care. One reason is that many patients treated at UCCs have acute needs that can be handled in isolation from other health care needs or conditions. Indeed, only an estimated 2.5 percent of urgent care visits in 2006 were for chronic or psychiatric conditions.5 UCC providers reported not wanting to manage patients long term or provide care that requires intense care coordination, such as for chronic conditions. One Jacksonville UCC director said, “[Patients] can’t have chronic illnesses for us to continue to see them. If they need a physical or have an earache, we’ll see them. But if [patients are] diabetic or hypertensive, we have to refer them to primary care because we do not follow that.”

Although UCCs were not seen as a major disruption to care coordination, they do not appear to emphasize care coordination. In general, UCC respondents reported little to no role in connecting patients with follow-up care. Some exceptions were hospital-owned or hospital-affiliated UCCs, which are more likely to have shared electronic health records that can facilitate referrals to other providers. In fact, some hospital-owned UCCs reported sometimes being able to schedule follow-up appointments for patients within their system faster than if the patients had gone through their primary care provider or scheduled an appointment directly.

Cost savings. The impact of urgent care centers on health care costs remains unclear. Respondents across the board reported a lack of data to show whether the growth of UCCs has generally saved money by diverting patients away from EDs or increased costs by drawing patients from primary care practices. As a Jacksonville health plan respondent explained, “The original model for urgent care was to keep people out of the ER. The more we started looking at that and reviewing the data, it was kind of a wash. Were we keeping them out of the ER? Or were we keeping them out of the primary care office and making it easy for folks to go someplace and get something taken care of that a PCP could’ve done?”

Still, many respondents speculated the presence of urgent care centers, with after-hours and weekend availability, diverts patients from EDs to lower-cost settings. For example, a San Francisco health plan respondent said patients often go to UCCs or EDs because they are unable to see their PCP during regular business hours. To the degree that UCCs are available, patients choose UCCs for nonemergencies. Also, in response to the growth of UCCs, more primary care practices are offering after-hours and weekend appointments as a competitive strategy to retain patients.

Other respondents believed UCCs did little to keep patients from using EDs and instead disrupted care by diverting patients from their primary care clinicians. For example, some noted that UCCs tend to locate in more-affluent, suburban areas and attract a relatively well-insured population rather than locating in inner-city areas where people may lack alternatives to the ED for urgent needs. A Detroit ED director said, “In the inner city, I don’t think urgent care centers have made any difference at all, because there are not too many urgent cares around. A lot of the inner-city population doesn’t have money or insurance anyway. So it doesn’t matter to them whether they go to the ED or to a UCC. If their costs are $100 or $200, they don’t care.”

Several respondents also speculated that UCCs add costs by diverting patients from primary care practices. An urgent care chain executive explained, “Urgent care can add to costs, in that people use these centers as primary care, rather than developing relationships with PCPs. Somebody like myself, I don’t have a chronic illness. I’m young. If I need to see a doctor, I just go to an urgent care center. I haven’t developed a PCP relationship. It probably adds to the cost of primary care.”

While the general consensus of health plan executives was that it is unclear whether urgent care centers result in overall cost savings, they appeared optimistic about UCCs’ potential as a cost-effective alternative to EDs. As evidence of their confidence that UCCs can help control costs, some health plans try to steer patients from EDs toward UCCs or PCPs through education and benefit designs that include higher copayments for ED visits relative to UCC visits.

As mentioned previously, some health plans have partnered with or purchased urgent care centers. For example, Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina has invested in FastMed Urgent Care to help the chain expand clinic locations across the state. Likewise, a Jacksonville health plan respondent said, “Everyone is trying to reduce medical expense while getting members to receive care in the most appropriate setting. [I would say that] 30 percent of patients that go to the ED could receive care in a less acute setting. If we can’t get a member to engage with their primary care physician, [our urgent care centers are] probably the next best step.”

![]() he more convenient access offered by urgent care centers may become increasingly attractive to patients and health systems in the coming years. Indeed, a few key factors—coverage expansions under health reform, a growing population and an aging population—are expected to increase the need for primary care capacity. One recent study predicted the United States would need 52,000 more primary care physicians by 2025.6 Given that many UCCs are staffed by primary care clinicians drawn from the existing supply of physicians, urgent care centers are unlikely to reduce PCP shortages. However, if primary care practices become more congested, stop accepting new patients or have longer appointment-wait times, UCCs could grow as an attractive alternative for patients. In addition, as more uninsured people gain subsidized private coverage under health reform, UCCs might become a viable option for those with problems finding or establishing a relationship with a PCP.

he more convenient access offered by urgent care centers may become increasingly attractive to patients and health systems in the coming years. Indeed, a few key factors—coverage expansions under health reform, a growing population and an aging population—are expected to increase the need for primary care capacity. One recent study predicted the United States would need 52,000 more primary care physicians by 2025.6 Given that many UCCs are staffed by primary care clinicians drawn from the existing supply of physicians, urgent care centers are unlikely to reduce PCP shortages. However, if primary care practices become more congested, stop accepting new patients or have longer appointment-wait times, UCCs could grow as an attractive alternative for patients. In addition, as more uninsured people gain subsidized private coverage under health reform, UCCs might become a viable option for those with problems finding or establishing a relationship with a PCP.

The potential for urgent care centers to generate cost savings could be expanded by making UCCs more accessible to low-income patients, many of whom currently have no viable alternative to EDs. While independent UCCs may see little financial incentive to enter underserved areas and to treat Medicaid and uninsured patients, hospitals, which could gain financially, may be more likely to add UCCs as a way to decrease ED use. Alternatively, if Medicaid managed care plans can justify higher payment rates for UCCs as way to control ED use, independent UCCs may be more willing to participate in Medicaid and serve areas with many Medicaid patients.

Growth in hospital ownership of or affiliation with UCCs may increase the degree to which UCCs become integrated with other care settings and provide coordinated care. This could change the role that urgent care plays—UCCs could be more capable of treating patients with more complex conditions if they can communicate with patients’ regular primary care providers through electronic health records. Also, as more health plans and hospitals purchase or partner with UCC chains, there could be opportunities to integrate UCCs into new models of care, such as an accountable care organizations (ACOs)—a group of providers that agree to be accountable for the quality, cost and overall care of a defined group of patients. To the degree that UCCs can divert nonemergency care needs from EDs, they could provide an option that ACOs might find cost effective.

| 1. | Urgent Care Association of America, The Case for Urgent Care, Naperville, Ill. (Sept. 1, 2011). |

| 2. | Weinick, Robin M., and Renée M. Betancourt, No Appointment Needed: The Resurgence of Urgent Care Centers in the United States, California HealthCare Foundation, Oakland, Calif. (September 2007). |

| 3. | O’Malley, Ann S., “After-Hours Access to Primary Care Practices Linked with Lower Emergency Department Use and Less Unmet Medical Need,” Health Affairs, Vol. 32, No. 1 (January 2013). |

| 4. | Mehrotra Ateev, et al., “Comparing Costs and Quality of Care at Retail Clinics with that of Other Medical Settings for 3 Common Illnesses,” Annals of Internal Medicine, Vol. 151, No. 5 (September 2009). |

| 5. | Weinick, Robin M., Rachel M. Burns and Ateev Mehrotra, “Many Emergency Department Visits Could Be Managed At Urgent Care Centers And Retail Clinics,” Health Affairs, Vol. 29, No. 9 (September 2010). |

| 6. | Petterson, Stephen M., et al., “Projecting U.S. Primary Care Physician Workforce Needs: 2010-2025,” Annals of Family Medicine, Vol. 10, No. 6 (November/December 2012). |

This study examined the impact of urgent care centers on access, coordination and overall costs of care in six communities—Detroit; Jacksonville, Fla.; Minneapolis; Phoenix; Raleigh-Durham, N.C.; and San Francisco. The communities were selected for their high penetration of urgent care centers and represent varying levels of provider integration. Two-person research teams conducted 30 telephone interviews with urgent care center executives and directors, hospital-based emergency department directors, and health plan network managers between May and November 2012. Interview notes were transcribed and jointly reviewed for quality and validation purposes. The study also utilized administrative data from the Urgent Care Association of America to identify urgent care centers currently operating in the six study sites. Urgent care centers in Detroit and Minneapolis were further categorized by the authors according to ownership arrangements, and their addresses were mapped using geocoding software.

This Research Brief was funded by the National Institute for Health Care Reform. The Institute is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, nonpartisan organization established by the International Union, UAW; Chrysler Group LLC; Ford Motor Company; and General Motors. The Institute contracts with the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC) to conduct health policy research and analyses to improve the organization, financing and delivery of health care in the United States.