RWJF Reform Community Report

July 2013

Ha T. Tu, Robert Mechanic, Ellyn R. Boukus, Kevin Draper

![]() haped by Oregon’s collaborative culture and activist history on health care issues, the Portland metropolitan area appears well prepared for national health reform, according to a new Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC) study of the region’s commercial and Medicaid insurance markets (see Data Source). Longstanding bipartisan support for health reform helped Oregon be in the vanguard of states authorizing a state health insurance exchange. With highly regarded leadership at the exchange’s helm, there is broad-based consensus that Oregon is among the states best prepared to roll out open enrollment on Oct. 1, 2013, although substantial work and testing still needs to be accomplished to meet the deadline.

haped by Oregon’s collaborative culture and activist history on health care issues, the Portland metropolitan area appears well prepared for national health reform, according to a new Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC) study of the region’s commercial and Medicaid insurance markets (see Data Source). Longstanding bipartisan support for health reform helped Oregon be in the vanguard of states authorizing a state health insurance exchange. With highly regarded leadership at the exchange’s helm, there is broad-based consensus that Oregon is among the states best prepared to roll out open enrollment on Oct. 1, 2013, although substantial work and testing still needs to be accomplished to meet the deadline.

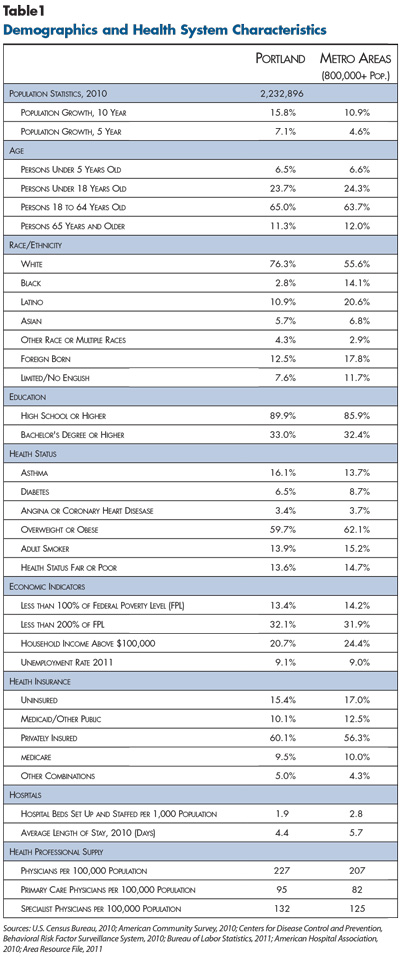

Oregon previously adopted many of the components of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA)—including small-group and individual, or nongroup, health insurance regulations and an expanded Medicaid program for low-income people. While ACA insurance requirements are more stringent than Oregon’s, they will not be completely novel to a community accustomed to significant government involvement in health insurance markets. However, Portland-area health plan executives, benefits consultants, insurance brokers and others are concerned about the impact of health reform on risk selection and premiums in the nongroup and small-group markets. Key factors likely to influence how national health reform plays out in the Portland area include:

Market Background

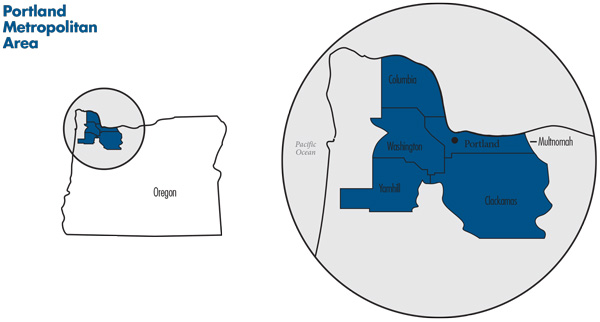

![]() he Portland metropolitan area spans five counties in northern Oregon—Clackamas, Columbia, Multnomah, Washington and Yamhill (see map). The region also includes two counties in southern Washington, but this study focuses solely on the Oregon portion of the region. Multnomah County, whose county seat is Portland, is the most populous county, followed by Washington and Clackamas. Together, these three counties account for more than 90 percent of the five-county Oregon population of 1.8 million people.

he Portland metropolitan area spans five counties in northern Oregon—Clackamas, Columbia, Multnomah, Washington and Yamhill (see map). The region also includes two counties in southern Washington, but this study focuses solely on the Oregon portion of the region. Multnomah County, whose county seat is Portland, is the most populous county, followed by Washington and Clackamas. Together, these three counties account for more than 90 percent of the five-county Oregon population of 1.8 million people.

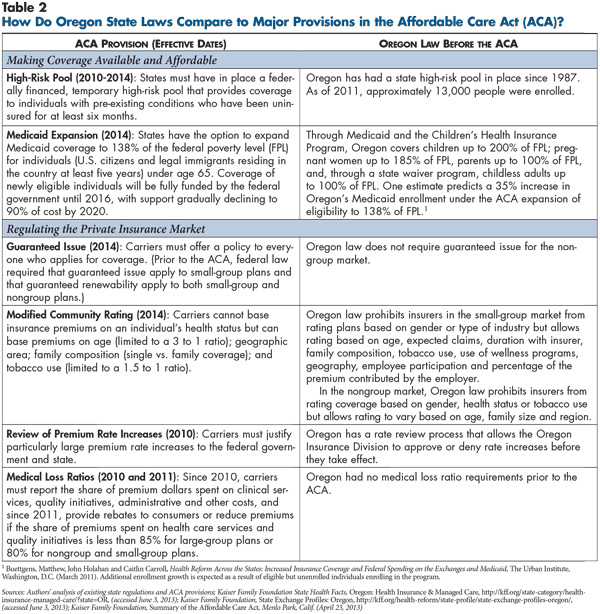

The Portland metropolitan area grew significantly in recent decades, particularly between 1990 and 2000 when population growth exceeded 25 percent. Growth slowed to 15.8 percent between 2000 and 2010, in part, because of the economic recession, but still outpaced the nationwide metropolitan average (10.9%) (see Table 1).

The region’s average income level, poverty rate and unemployment rate differ little from nationwide metropolitan averages, but the area’s education levels are slightly higher than average. Portland has a much higher proportion of white, non-Latino residents (76.3%) compared to the metropolitan average of 55.6 percent, despite a recent surge in the region’s Latino population.

Historically, the region’s economy relied heavily on lumber and agriculture. As these industries declined, the high-tech sector boomed, earning Portland the nickname of “the Silicon Forest.” The green jobs sector, including renewable energy and sustainable architecture, is another growth area.

Portland employers, including newer tech companies, are mostly small to mid-sized firms. With the notable exceptions of federal, state and local public employers, several health systems, and Nike and Intel, larger employers in Portland tend to have workforces numbering in the hundreds, rather than thousands, of employees. Statewide, 54 percent of workers are employed by firms with fewer than 50 employees, compared to 45 percent nationwide.1 The greater Portland area has a slightly lower uninsurance rate and a slightly higher proportion of residents with private health coverage compared to the average metropolitan area. However, after holding steady from 2006 to 2010, the proportion of private-sector employers offering health coverage dropped from 60 percent in 2010 to 53 percent in 2011.2

State Background and Regulatory Approach

![]() regon is noteworthy for both an activist and collaborative culture related to health care issues. Respondents noted that while competition among health plans and providers is robust, relationships generally are not contentious. In fact, there is a high degree of engagement and cooperation among competitors. Several organizations—for example, the Oregon Health Leadership Council, Oregon Coalition of Health Care Purchasers and Oregon Healthcare Quality Corp.—unite various stakeholders around common goals, including slowing health care cost growth.

regon is noteworthy for both an activist and collaborative culture related to health care issues. Respondents noted that while competition among health plans and providers is robust, relationships generally are not contentious. In fact, there is a high degree of engagement and cooperation among competitors. Several organizations—for example, the Oregon Health Leadership Council, Oregon Coalition of Health Care Purchasers and Oregon Healthcare Quality Corp.—unite various stakeholders around common goals, including slowing health care cost growth.

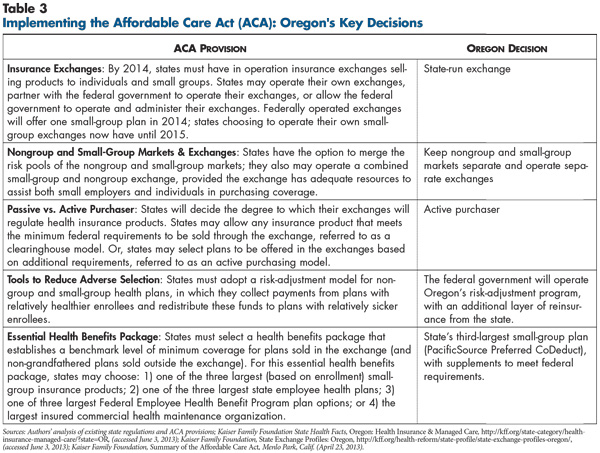

Oregon’s collaborative spirit also is reflected in bipartisan support for health care reform. In June 2011, Oregon was among the first states to pass legislation enacting a state-run health insurance exchange—an action consistent with the state’s longstanding history of expanding access to insurance coverage (see Table 2 and Table 3). In Oregon’s case, the guiding principle for coverage expansion has been that providing some coverage for everybody—or at least more people—is better than providing comprehensive coverage for fewer people.

This guiding principle is exemplified by the design of Oregon’s Medicaid program, the Oregon Health Plan (OHP). Since the early 1990s, under a federal waiver, OHP has provided coverage to childless adults who are not disabled with incomes up to 100 percent of poverty. Facing budget shortfalls, Oregon in 2003 split OHP into two coverage groups: OHP Plus for eligible pregnant women, parents and children and OHP Standard for other low-income adults. OHP Standard covers a limited set of core benefits, including hospital and physician services and prescription drugs, but excludes other services, such as nonemergency dental care. Since 2004, Oregon has limited OHP Standard enrollment because of budget contraints, first by closing the program to new applicants, then by instituting a lottery in 2008. From 2008 to 2011, 53,300 applicants statewide received OHP Standard coverage from a pool of nearly 94,000 who applied.3

Oregon plans to expand Medicaid eligibility under the ACA option in 2014. The state estimates the expansion will cover roughly 240,000 newly eligible and 20,000 previously eligible Oregonians.4 The expansion may have a less pronounced impact than in some states since Oregon already covers some childless adults with incomes up to 100 percent of poverty. State officials expected that current OHP Standard enrollees—as well as those currently eligible but not selected by the lottery—will be designated as newly eligible for Medicaid and qualify for an enhanced federal matching rate under the ACA.

State-Funded Private Insurance

![]() regon also has used three private coverage initiatives. Two provide subsidies to low-income people or families to purchase private insurance, and the third is a high-risk pool in operation since 1987, the Oregon Medical Insurance Pool (OMIP). The high-risk pool provides coverage to difficult-to-insure people with pre-existing conditions and is funded 50/50 by member premiums and assessments on health carriers. OMIP premiums are capped at 125 percent of the average nongroup market premium. The ACA provided federal funding and required all states to offer a temporary high-risk pool program. OMIP operates the federal high-risk pool, but enrollment in the federal option was suspended in March 2013 because of mounting budget pressures.

regon also has used three private coverage initiatives. Two provide subsidies to low-income people or families to purchase private insurance, and the third is a high-risk pool in operation since 1987, the Oregon Medical Insurance Pool (OMIP). The high-risk pool provides coverage to difficult-to-insure people with pre-existing conditions and is funded 50/50 by member premiums and assessments on health carriers. OMIP premiums are capped at 125 percent of the average nongroup market premium. The ACA provided federal funding and required all states to offer a temporary high-risk pool program. OMIP operates the federal high-risk pool, but enrollment in the federal option was suspended in March 2013 because of mounting budget pressures.

Under ACA rules, health insurance companies in 2014 will no longer be permitted to deny coverage because of pre-existing conditions, eliminating the need for high-risk pools like OMIP. Oregon expects OMIP enrollees to transition to the state health insurance exchange, the private insurance market outside the exchange or OHP.

Commercial Market Regulatory Environment

![]() regon already requires a fair number of consumer protections in the commercial health insurance market. The extent to which these regulations align with ACA requirements varies by market segment. Oregon requires both guaranteed issue and guaranteed renewability in the small-group market (2-50 employees), but the state’s rating restrictions are significantly less stringent than ACA small-group requirements. Currently in Oregon, rates can vary by age, duration with insurer, family composition, tobacco use, wellness program participation, geographic area and expected claims but not gender or industry. Unlike many states, Oregon permits small-group rates to vary based on employee participation and the percentage of employer premium contribution.

regon already requires a fair number of consumer protections in the commercial health insurance market. The extent to which these regulations align with ACA requirements varies by market segment. Oregon requires both guaranteed issue and guaranteed renewability in the small-group market (2-50 employees), but the state’s rating restrictions are significantly less stringent than ACA small-group requirements. Currently in Oregon, rates can vary by age, duration with insurer, family composition, tobacco use, wellness program participation, geographic area and expected claims but not gender or industry. Unlike many states, Oregon permits small-group rates to vary based on employee participation and the percentage of employer premium contribution.

Oregon’s consumer protections in the nongroup market are strong in some respects. Modified community rating rules allow rate variation based only on age, family size and region. Oregon prohibits rating by tobacco use, which the ACA allows. Oregon does not require guaranteed issue in the nongroup market but does mandate guaranteed renewability for existing policies. The inability to charge higher premiums or rescind coverage to sicker people discourages health plans from offering coverage to these people in the first place, which has tended to push this group into the state high-risk pool.

Highly Competitive Commercial Insurance Market

![]() arket observers universally characterized Portland’s commercial insurance market as very competitive, with no dominant health plan among about 10 plans overall. The three leading commercial plans are Regence Blue Cross Blue Shield of Oregon, Kaiser Permanente Northwest and Providence Health Plan. Regence and Kaiser rank a close first and second in commercial enrollment—with Regence leading in self-insured lives and Kaiser in fully insured lives—followed by Providence. Regence and Providence are local nonprofit plans, while nonprofit Kaiser maintains a strong community presence despite having a larger national footprint. Providence Health Plan is owned by Providence Health & Services, the market’s largest hospital system, but the health plan is not tied exclusively to its parent. Instead, the Providence plan offers broad provider networks, including other major providers.

arket observers universally characterized Portland’s commercial insurance market as very competitive, with no dominant health plan among about 10 plans overall. The three leading commercial plans are Regence Blue Cross Blue Shield of Oregon, Kaiser Permanente Northwest and Providence Health Plan. Regence and Kaiser rank a close first and second in commercial enrollment—with Regence leading in self-insured lives and Kaiser in fully insured lives—followed by Providence. Regence and Providence are local nonprofit plans, while nonprofit Kaiser maintains a strong community presence despite having a larger national footprint. Providence Health Plan is owned by Providence Health & Services, the market’s largest hospital system, but the health plan is not tied exclusively to its parent. Instead, the Providence plan offers broad provider networks, including other major providers.

In addition to the three leading plans, the commercial market has an abundance of active smaller players, including national for-profit carriers—United, Aetna, Cigna—as well as local/regional companies—some nonprofit (PacificSource) and others for-profit (Health Net, LifeWise and Moda Health, which was formerly known as ODS). As in many markets, the national carriers have a larger presence in the self-insured market than the fully insured market. A number of strong regional third-party administrators also compete vigorously for self-insured business.

Over the past five years, overall commercial enrollment declined in greater Portland because of the economic downturn. However, Kaiser maintained enrollment levels and consequently increased market share. Another significant shift in competitive balance in recent years resulted from Regence’s loss of high-profile public accounts—covering state employees and teachers—to Providence and ODS, respectively. Regence remains a strong brand and reportedly still receives the best provider discounts, although this advantage is modest and shrinking, according to market observers.

Premium levels in Portland historically have been moderate, in part, because underlying price pressures appear to be less intense than in many markets. This reflects the relative efficiency of Portland providers overall, as well as the absence of a single dominant hospital system exercising outsized leverage. Most respondents considered premium increases in recent years to be moderate—“bearable,” according to one benefits consultant—the result of plans competing vigorously for market share in a stagnant economic climate.

Middle-of-the-Road Employer Health Benefits

![]() ith the exception of Kaiser’s closed-model HMO products, Portland’s commercial market is dominated by PPOs. Product designs are largely similar across the small- and large-group segments, with differences primarily in premiums and out-of-pocket cost-sharing requirements. Among large groups, individual deductibles in the $500-$1,000 range are common, and among small groups, individual deductibles average about $2,000, though the range is wide. Except for office visits, which tend to be subject only to fixed copayments, the use of coinsurance where patients pay a percentage of the bill is the norm for most services in PPO products.

ith the exception of Kaiser’s closed-model HMO products, Portland’s commercial market is dominated by PPOs. Product designs are largely similar across the small- and large-group segments, with differences primarily in premiums and out-of-pocket cost-sharing requirements. Among large groups, individual deductibles in the $500-$1,000 range are common, and among small groups, individual deductibles average about $2,000, though the range is wide. Except for office visits, which tend to be subject only to fixed copayments, the use of coinsurance where patients pay a percentage of the bill is the norm for most services in PPO products.

Kaiser HMO products, which historically offered first-dollar coverage like most HMOs, have evolved to include a wide range of products requiring different levels of cost sharing. HMOs with deductibles, which now account for more than half of Kaiser’s group enrollment, “took off in the last five years [during] the recession...as those small [employers] who didn’t drop coverage had to find ways of tamping down premiums,” according to one broker. While that observation was about Kaiser products, it also applies to commercial products more broadly. Respondents noted that, prior to the economic downturn, high-deductible health plans (HDHPs) had achieved moderate penetration in the Portland market, but as in many markets, the downturn accelerated the move to HDHPs—especially by small firms. Estimates of the HDHP share of total small-group enrollment ranged from “over half” to 80 percent. In recent years, it has become common practice for mid-sized and larger employers to offer HDHPs, but these employers are far less likely than small firms to make the HDHP a full-replacement product. Instead, they usually offer the HDHP alongside one or two other choices, such as a Kaiser HMO and a conventional PPO. Increasingly in these cases, employers are making the HDHP the base option for premium contributions, requiring employees to “buy up” to more generous coverage.

Fairly Competitive Market Among Efficient Providers

![]() esides Kaiser, Portland has five main hospital systems: Providence Health & Services, Legacy Health, Oregon Health & Sciences University Healthcare, Adventist Health, and Tuality Healthcare. All are local or regional nonprofits; national for-profit hospital chains have no presence in Portland. The two largest systems, Providence and Legacy, are roughly equal in size, with five to six hospitals totaling 1,000-plus beds each. Providence is regarded by some market observers as the higher-end provider; Legacy is less expensive, but its brand is not considered quite as strong. OHSU is the public academic medical center and Oregon’s major tertiary referral center. Adventist and Tuality are much smaller systems, with one hospital of 302 licensed beds and two hospitals with 215 licensed beds, respectively.

esides Kaiser, Portland has five main hospital systems: Providence Health & Services, Legacy Health, Oregon Health & Sciences University Healthcare, Adventist Health, and Tuality Healthcare. All are local or regional nonprofits; national for-profit hospital chains have no presence in Portland. The two largest systems, Providence and Legacy, are roughly equal in size, with five to six hospitals totaling 1,000-plus beds each. Providence is regarded by some market observers as the higher-end provider; Legacy is less expensive, but its brand is not considered quite as strong. OHSU is the public academic medical center and Oregon’s major tertiary referral center. Adventist and Tuality are much smaller systems, with one hospital of 302 licensed beds and two hospitals with 215 licensed beds, respectively.

Provider competition is limited to some extent by geography. For instance, Providence has a presence on the west side of Portland, while Legacy does not. On the whole, however, respondents characterized Portland as having neither the unbalanced leverage nor the aggressive, contentious provider-plan relationships seen in some markets with a dominant hospital system. One health plan executive observed that “no hospital is an absolute must-have relative to the others.”

Portland hospitals are efficient relative to their counterparts in other markets. In the aggregate, Portland hospitals have low per-capita inpatient costs for both Medicare and commercial payers, according to a 2010 Milliman report.5

The Portland market has seen significant and growing hospital employment of physicians, though not to the extent observed in some markets. The market does not have a significant base of large, independent medical groups, and many physicians remain in small, independent practices. Among the largest systems—Providence, Kaiser and Legacy—which all employ physicians, Providence is the most aggressive in hiring physicians and acquiring practices, doubling its employed physicians from 2007 to 2011 to nearly 450. However, independent physicians still account for the majority of the medical staff at Providence hospitals.

Unlike in Medicaid, where many safety net providers assume financial risk for patient care, Portland providers contracting with health plans in the commercial market typically do not bear risk and usually are paid on a fee-for-service basis. The market has some large independent practice associations, but they do not take risk. Provider risk bearing continues to be a feature of the Medicare Advantage market, but there are currently no Medicare ACOs in the community.

Plans Introduce Limited Networks

![]() istorically, broad provider networks have been the rule for Portland’s commercial PPO products. Several respondents noted that, among non-Kaiser plans, there has been little, if any, differentiation based on provider networks. Recently, the market has seen some movement toward limited-network products, though these products have yet to gain significant traction.

istorically, broad provider networks have been the rule for Portland’s commercial PPO products. Several respondents noted that, among non-Kaiser plans, there has been little, if any, differentiation based on provider networks. Recently, the market has seen some movement toward limited-network products, though these products have yet to gain significant traction.

Respondents noted that various tiered-network products, where enrollees have lower cost sharing if they use a provider in the preferred tier, have been around for a number of years “in a small way.” Some products were targeted specifically to groups with fewer than 100 people—an especially price-conscious segment. The premium differentials relative to full-network products were not large enough to attract “more than a handful” of larger employers, according to a benefits consultant.

Within the past year, health plans have introduced narrow-network products, sometimes in collaboration with a provider system. One example is LifeWise, a subsidiary of Premera Blue Cross of Washington, that entered an exclusive arrangement with the Providence system. As of mid-2013, LifeWise, which historically emphasized broad networks, will offer only products based on the Providence system. At the same time, Health Net, which failed to renew a contract with Providence, reportedly is discussing an exclusive arrangement with the Legacy system. Other plans and providers reportedly are exploring various narrow-network arrangements.

The region’s largest plan, Regence, recently rolled out Oregon Select, a portfolio of five provider networks based on the five major non-Kaiser hospital systems in the market. Oregon Select can be configured as either a tiered-network product (when paired with a standard PPO) or a narrow-network product. For the commercial group market, Regence is offering Oregon Select as tiered networks—for example, an employer buys a conventional PPO with a broad network but chooses a lower-priced provider, such as Adventist, as a preferred tier requiring lower enrollee out-of-pocket costs. For the nongroup market, however, where Regence has withdrawn PPO products, Regence is selling Oregon Select as a narrow-network product. Looking to 2014, the nongroup market is expected to grow substantially from a rather limited base, and Oregon Select is viewed as a central part of Regence’s competitive strategy for the nongroup market.

While Portland’s fledgling limited-network commercial products involve at least some collaboration between plans and providers, to date they generally have not involved any innovation in payment methods, which remain almost entirely fee for service. Plans and providers are discussing new risk-sharing payment mechanisms where providers assume more responsibility for the cost of care—and some respondents believed the market is moving inevitably in that direction—but no concrete risk-sharing collaborations have been implemented. In a commercial market where providers historically have not accepted risk, some observers questioned the capacity—especially of the smaller systems and physician organizations—to take on downside risk.

Innovative Medicaid Managed Care Plans

![]() n Oregon, enrollment in managed care is mandatory for most Medicaid populations, with some notable exceptions: people dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, American Indians, people with end-stage renal disease, and those in areas with inadequate plan capacity. Statewide, nearly 90 percent of OHP members are enrolled in managed care. Historically, most of the roughly 270,000 OHP enrollees in greater Portland received coverage through regional, nonprofit managed care organizations (MCOs). OHP contracted with separate organizations for physical, mental and dental care coverage. Portland has been served by five physical health plans, three mental health plans administered by Multnomah, Clackamas and Washington counties, and eight dental organizations. The two largest Medicaid plans are CareOregon, serving approximately 100,000 members in the Portland area, and FamilyCare, which provides integrated physical and mental health care coverage for about 45,000-50,000 enrollees. Provider networks of these MCOs overlapped significantly, with most hospitals and at least half of primary care physicians contracting with both organizations.

n Oregon, enrollment in managed care is mandatory for most Medicaid populations, with some notable exceptions: people dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, American Indians, people with end-stage renal disease, and those in areas with inadequate plan capacity. Statewide, nearly 90 percent of OHP members are enrolled in managed care. Historically, most of the roughly 270,000 OHP enrollees in greater Portland received coverage through regional, nonprofit managed care organizations (MCOs). OHP contracted with separate organizations for physical, mental and dental care coverage. Portland has been served by five physical health plans, three mental health plans administered by Multnomah, Clackamas and Washington counties, and eight dental organizations. The two largest Medicaid plans are CareOregon, serving approximately 100,000 members in the Portland area, and FamilyCare, which provides integrated physical and mental health care coverage for about 45,000-50,000 enrollees. Provider networks of these MCOs overlapped significantly, with most hospitals and at least half of primary care physicians contracting with both organizations.

CareOregon and FamilyCare are widely regarded as innovative, having implemented a range of alternative payment mechanisms and care delivery models not seen in the commercial sector, at least to the same extent. On the payment side, the two Medicaid plans—unlike their commercial counterparts—have adopted contracting arrangements beyond fee for service. Some primary care clinics in their networks are paid on a capitated basis—fixed monthly per-member amounts to provide care for each Medicaid enrollee. Both plans also have pay-for-performance programs where clinics can earn increases of up to 33 percent based on quality and efficiency criteria.

In care delivery, CareOregon is known for its Primary Care Renewal program, a partnership with primary care practices to establish patient-centered medical homes. The program began in 2007 with a handful of safety net clinics and now includes about 60 clinics serving 60 percent to 70 percent of CareOregon enrollees.

Both plans also offer multidisciplinary case management programs focused on the most medically and socially complex patients. For example, CareOregon’s CareSupport program identifies patients through predictive modeling and referrals by physicians or caseworkers and then assigns the patients to multidisciplinary care teams that help with self-care management, care coordination and navigating community resources.6 Similarly, FamilyCare has a longstanding program where navigators—nurses and social workers—work with patients and their primary care physicians to help them effectively navigate the health care system.

Transition to Coordinated Care Organizations

![]() regon recently embarked on an ambitious transformation of Medicaid financing and organization centered on the formation of coordinated care organizations, or CCOs, which began operating in August 2012. Modeled after accountable care organizations, CCOs are required to integrate and coordinate coverage for physical, mental and, beginning July 2014, dental care within a global budget. Building on the experience of their MCO predecessors, CCOs also are expected to deliver care more efficiently. Through a Medicaid 1115 waiver, the federal government agreed to provide $1.9 billion for the program over five years contingent on the state reducing annual per-capita Medicaid spending growth by at least two percentage points (from a base rate of 5.4%) by mid-2015.7

regon recently embarked on an ambitious transformation of Medicaid financing and organization centered on the formation of coordinated care organizations, or CCOs, which began operating in August 2012. Modeled after accountable care organizations, CCOs are required to integrate and coordinate coverage for physical, mental and, beginning July 2014, dental care within a global budget. Building on the experience of their MCO predecessors, CCOs also are expected to deliver care more efficiently. Through a Medicaid 1115 waiver, the federal government agreed to provide $1.9 billion for the program over five years contingent on the state reducing annual per-capita Medicaid spending growth by at least two percentage points (from a base rate of 5.4%) by mid-2015.7

In August 2012, Portland’s numerous Medicaid MCOs were consolidated into two CCOs: Health Share of Oregon and FamilyCare. The state gave the new entities considerable latitude in determining their structure and organization, and this approach is reflected in the very different forms the two CCOs have adopted. The FamilyCare CCO is a natural extension of the FamilyCare MCO, which already offered integrated care for physical and mental health services. In contrast, the Health Share CCO brings together a much larger, more diverse set of organizations, including four physical health plans (CareOregon, Providence, Kaiser and Tuality Health Alliance); the three mental health plans operated by Washington, Multnomah and Clackamas counties; five health systems (OHSU, Providence, Legacy, Tuality and Adventist); and a social services agency (Central City Concern).

Portland’s newly formed CCOs face an immediate challenge of operating successfully under the cost constraints of the Medicaid waiver while meeting new quality targets. CCOs receive capitated payments. Under the waiver, payments to CCOs will increase at a rate two percentage points lower than the historical trend. The state also will introduce pay for performance into the CCO program; over time, the capitation rate will decline, while the proportion of funding tied to meeting defined performance metrics will increase. The CCOs also are expected to expand the use of alternative payment methods with their partner provider organizations. The state plans to offer technical assistance with a “starter set” of models that include patient-centered medical home payments, bundled payments, risk-sharing arrangements and other types of pay-for-performance bonuses for providers.

Key unresolved questions about the Health Share CCO center on how member organizations will integrate and coordinate functions. Currently, the four physical health plans in Health Share continue to manage their Medicaid enrollees separately, under subcapitation contracts with the CCO. Three of the four plans also operate commercial lines of business, and all the plans have separate administrative systems, provider networks, payment methods and medical-management protocols. The plans reportedly have little interest in consolidating administrative functions, so they will operate independently under the umbrella CCO legal structure. However, member plans will work together on key common objectives like reducing emergency department use. They also may standardize certain operations like non-emergency medical transportation and drug formularies. In contrast to the physical health plans, the three county-run mental health plans are working to consolidate administrative functions and standardize certain functions, including utilization management and payment policy.

Health Share plans are collaborating to improve care coordination for high-cost patients. With a federal Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation grant, Health Share is implementing several interventions, including community outreach teams to work with patients at risk of hospitalization, intensive nurse and pharmacist support for patients at high risk of hospital readmission, and short-term intensive case management for psychiatric inpatients discharged to the community. These efforts have staff from Health Share working alongside staff from the participating plans, medical clinics and community service providers.

CCOs are viewed as the leading edge of a broader effort by Oregon to transform the delivery of health care. CCOs initially will be responsible for Medicaid enrollees, but the state has signaled intent to expand CCO coverage over time to state employees and possibly to state residents purchasing qualified health benefits through the state exchange. While Medicaid is ahead of the commercial sector in efforts to drive delivery system and payment reforms, it remains to be seen whether CCOs can control costs sufficiently to meet the waiver targets and improve—or at least maintain—Medicaid quality levels. It is also uncertain how quickly the CCO model can be expanded to include commercial enrollees.

Preparations for Reform

![]() pen enrollment in the insurance exchange is scheduled to begin Oct. 1, 2013, with the Medicaid expansion following on Jan. 1, 2014. Compared to other communities and states, Portland and Oregon appear well positioned to implement these changes in a timely manner. However, much complex work remains to be done, and significant testing of exchange data systems is not slated to begin until late summer.

pen enrollment in the insurance exchange is scheduled to begin Oct. 1, 2013, with the Medicaid expansion following on Jan. 1, 2014. Compared to other communities and states, Portland and Oregon appear well positioned to implement these changes in a timely manner. However, much complex work remains to be done, and significant testing of exchange data systems is not slated to begin until late summer.

The state exchange, Cover Oregon, will follow an active-purchaser model and select which health plans can sell products on the exchange. Specifically, Cover Oregon is requiring carriers to report on quality-improvement and cost-containment strategies and is limiting the number of products each carrier may offer in a given metal tier—products will be designated as bronze, silver, gold or platinum in the exchange. Other key decisions include keeping the small-group and nongroup markets separate and deferring to the federal government on risk adjustment and reinsurance, although Oregon plans to add another layer of reinsurance aimed at further stabilizing the nongroup market.

Oregon selected its third-largest small-group plan, PacificSource Preferred CoDeduct, as the benchmark for essential health benefits. Some respondents expressed concern that this product’s comprehensive benefits may be unaffordable, but one observer pointed out that it was the most affordable among several options considered by the state. And, a benefits consultant contended that the underlying problem stems from a disparity between the level of benefits now prevalent in Portland’s small-group market and the far more comprehensive ACA requirements.

As noted earlier, Oregon’s history and culture of collaboration helped foster bipartisan support for health reform. The state is considered well positioned in terms of political, legislative and financial readiness to have the exchange up and running by the deadline. According to insiders, the key issues remaining are technological challenges of ensuring data systems operate properly when the exchange opens for business. In part, respondents ascribed these challenges to the tight timeframe required by the federal government, coupled with a lack of timely federal guidance.

In addition, Oregon will exceed ACA requirements by incorporating Medicaid enrollment and renewal—not just eligibility screening—into the exchange platform. Also, despite a federal delay of the Small Business Health Options Program, or SHOP, by one year, Cover Oregon is expected to move forward with its SHOP as originally planned, offering a range of options beyond the ACA requirements.

Unlike some markets, Portland health plans generally have been enthusiastic about participating in the exchange, and respondents expressed no concerns about adequate plan participation. By May 2013, 12 plans intended to offer nongroup products, and eight planned to offer SHOP products.

Uncertainties in Setting Exchange Premiums

![]() cross the country, there are likely to be similar questions and concerns about setting premiums for products offered in the exchanges, including:

cross the country, there are likely to be similar questions and concerns about setting premiums for products offered in the exchanges, including:

Along with these broader concerns, there are some ways these issues could play out more specifically in the Portland market.

Actuarial anxiety. As in other markets, Portland health plan respondents were anxious about pricing products appropriately—low enough to be competitive and high enough not to lose money. The plans are grappling with uncertainty about how sick the newly insured population will be and how intensively new enrollees will use services. If plans set premiums too high, they would cede market share to rivals and would have to return excess premiums to policyholders since the resulting medical loss ratios might not meet ACA standards. But, if plans set premiums too low, not only would plans lose money, but the state’s annual rate review might prevent plans from raising future premiums sufficiently to offset the error.

Oregon commissioned a study, commonly known as the Wakely Report, to assess the ACA’s impact on prices in the nongroup and small-group markets. The report estimated that monthly premiums in the nongroup market would increase on average by 38 percent, while the impact on small-group premiums would be much lower (4%).8 The report suggested that once cost-sharing limits and federal premium subsidies for income-eligible people are taken into account, overall out-of-pocket costs to consumers are likely to decrease from today’s levels. Several respondents were notably more pessimistic about future premium increases than the Wakely report and expected rate shock to hit the small-group and nongroup markets. However, when Oregon released health plans’ proposed 2014 rates for nongroup and small-group coverage, the rates were lower overall than many market observers had feared. Prices for similar products varied considerably—for example, monthly bronze-level premiums for a 40-year-old nonsmoker ranged from $195 to $401.9 After the public rate disclosure, some health plans that had submitted high initial rates requested to lower their rates after seeing competitors’ proposed rates. In addition, the Insurance Division disallowed a portion of every proposed rate submitted for review by health plans. As a result, when final 2014 rates were released in June, the range of bronze-level premiums for a 40-year-old nonsmoker had dropped to $166 to $274 per month—reflecting a substantial reduction in both average price and variation in prices.10

Shifts in competitive dynamics. Among the commercial health plans, many respondents viewed Kaiser as the plan most likely to gain a competitive advantage under reform, because of its unique experience managing care and operating in a capitated environment. Views were mixed about the outlook for other commercial health plans. Many respondents expected to see consolidation and a resulting decrease in competition among commercial plans over the next several years, with the most likely scenario being absorption of smaller plans by the leading local plans.

Market observers expected to see more collaboration over the next few years between health plans and providers that would involve risk sharing and a joint effort to contain total costs by managing care, instead of just negotiating provider price discounts. Several suggested that the market’s collaborative environment and general lack of aggressive, adversarial plan-provider relationships would create favorable conditions for such endeavors. At the same time, some cautioned that these fledgling partnerships may be held back by both providers’ and plans’ lack of experience with risk sharing in Portland’s commercial sector.

To date, provider consolidation and hospital-physician alignment have been less intense in Portland than in some markets. Several respondents expected to see these trends accelerate. One health plan CEO suggested there would be more consolidation among providers than health plans, with the major health systems acquiring physician practices more aggressively.

Changes in product design. Several respondents predicted a pronounced shift toward limited-network products on the exchange. Limiting provider networks was widely seen as the only tool left to health plans to prevent explosive growth in premiums given the level of benefits required by the ACA. Some respondents expected that employers—especially small and mid-sized firms—increasingly will adopt a defined-contribution approach to health benefits, where they give workers a fixed amount to purchase their own coverage.

Role of brokers. Portland is very much a broker-driven market, with 95 percent of small-group products and 70 percent of nongroup products estimated to be sold through brokers. Acknowledging that brokers will be vital to driving volume to the exchange, Cover Oregon officials are prepared to have brokers play a major role in selling exchange products. Each health plan will determine its own broker commissions and build these into premiums; it is uncertain how commissions for exchange products will compare to those currently paid for small-group and nongroup products. In the small-group market, brokers are expected to continue playing a pivotal role for the foreseeable future, given that many small employers use brokers as their de facto human resources department. In contrast, the longer-term outlook for brokers in the nongroup market is less clear; some expect their role to diminish gradually as consumers learn to navigate the exchange’s website to shop directly for insurance products.

Employer responses. As in other markets, Portland respondents had a variety of concerns about strategies employers might pursue to avoid triggering certain ACA requirements. For instance, they suggested some employers might keep work hours below 30 hours a week to reduce their full-time employee count or drop coverage altogether. Also, progressively smaller employers might move to self-insurance to avoid excise taxes, community rating and essential health benefits requirements under the ACA, and some respondents expressed concerns about the ability of such employers to handle the risk. Oregon law prohibits the sale of stop-loss insurance—secondary coverage an employer buys that covers the cost of medical claims beyond a certain threshold—to groups smaller than 50; this restriction eventually will apply to groups up to 100 as a new definition of “small group” takes effect under the ACA in 2016.

Medicaid. The extent to which Medicaid CCOs will play a role on the exchange is uncertain. CCOs without existing commercial business lines would have to gain a commercial license to sell exchange products. Among the commercial plans that have applied to sell products on the exchange, there are some—including Kaiser and ODS—that also sell Medicaid managed care products. As members of the Health Share CCO, there is potential for these plans to offer CCO-like products on the exchange. One respondent noted that if Health Share were to sell products on the exchange, it would be competing against some of its member organizations.

The planned phaseout of OHP Standard and its lottery-based enrollment system is not expected to create much disruption because 90 percent of current OHP enrollees already receive OHP Plus coverage and the Standard benefit package is so limited. The transition from Standard to Plus coverage is even expected to save Oregon money, thanks to enhanced federal Medicaid matching rates; a recent analysis estimates total savings to be $1.1 billion.11

Issues to Track

Notes

| 1. | U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages, Table 4, Private Industry by Supersector and Size of Establishment: Establishments and Employment, First Quarter 2011, by State, http://www.bls.gov/cew/ew11table4.pdf (accessed on June 17, 2013). |

| 2. | Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Center for Financing, Access and Cost Trends, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey-Insurance Component, Table IX.A.1(2011), Health Insurance Offer, Eligibility and Take Up Rates for Private-Sector Establishments and Employers for Areas within States, United States 2011, http://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_stats/summ_tables/insr/state/series_9/2011/tixa1.htm (accessed April 6, 2013). |

| 3. | Oregon Health Authority, Division of Medical Assistance Programs, CMS Section 1115 Quarterly Report, Oregon Health Plan 2, Salem, Ore. |

| 4. | State Health Access Data Assistance Center, Minneapolis, Minn., Oregon Health & Sciences University, Portland, Ore., and Manatt Health Solutions, New York, N.Y., Estimated Financial Effects of Expanding Oregon’s Medicaid Program under the Affordable Care Act (2014-2020) (February 2013). |

| 5. | Pennyson, Bruce, et al., High Value for Hospital Care: High Value for All?, Client Report for National Business Group on Health, Milliman, New York, N.Y. (March 18, 2010). |

| 6. | Klein, Sarah, and Douglas McCarthy, CareOregon: Transforming the Role of a Medicaid Health Plan from Payer to Partner, The Commonwealth Fund, New York, N.Y. (July 2010). |

| 7. | To meet the terms of the waiver OHP, must demonstrate a 1-percentage point reduction in per capita spending growth, from 5.4 percent annual growth in base year 2011 to 4.4 percent in the second year of the demonstration (July 2013-July 2014), and another 1-percentage point reduction to a 3.4 percent growth rate in the third year of the demonstration (July 2014-July 2015) and subsequent years. |

| 8. | Wakely Consulting Group, Actuarial Analysis: Impact of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) on Small Group and Individual Market Premiums in Oregon, Englewood, Colo. (July 31, 2012). |

| 9. | Galewitz, Phil, “Competition Spurs Two Oregon Insurers to Lower Proposed Rates,” The Lund Report (May 13, 2013). |

| 10. | Budnick, Nick, “Oregon Slashes 2014 Individual Health Premiums as Much as 35 Percent,” The Oregonian (June 26, 2013). |

| 11. | Pennyson (2010). |

Data Source

As part of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s (RWJF) State Health Reform Assistance Network initiative, the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC) examined commercial and Medicaid health insurance markets in eight U.S. metropolitan areas: Baltimore; Portland, Ore.; Denver; Long Island, N.Y.; Minneapolis/St. Paul; Birmingham, Ala.; Richmond, Va.; and Albuquerque, N.M. The study examined both how these markets function currently and are changing over time, especially in preparation for national health reform as outlined under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010. In particular, the study included a focus on the impact of state regulation on insurance markets, commercial health plans’ market positions and product designs, factors contributing to employers’ and other purchasers’ decisions about health insurance, and Medicaid/state Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) outreach/enrollment strategies and managed care. The study also provides early insights on the impact of new insurance regulations, plan participation in health insurance exchanges, and potential changes in the types, levels and costs of insurance coverage.

This primarily qualitative study consisted of interviews with commercial health plan executives, brokers and benefits consultants, Medicaid health plan executives, Medicaid/CHIP outreach organizations, and other respondents—for example, academics and consultants—with a vantage perspective of the commercial or Medicaid market. Researchers conducted 17 interviews in the Portland market between October 2012 and March 2013. Additionally, the study incorporated quantitative data to illustrate how the Portland market compares to the other study markets and the nation. In addition to a Community Report on each of the eight markets, key findings from the eight sites will also be analyzed in two publications, one on commercial insurance markets and the other on Medicaid managed care.