RWJF Reform Community Report

September 2013

Ha T. Tu, Chapin White, Ellyn R. Boukus, Kevin Draper

![]() t first glance, New York and the Long Island metropolitan area appear well positioned for smooth implementation of the federal Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010, according to a new Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC) study of Long Island’s commercial and Medicaid insurance markets (see Data Source). Key ACA reforms—expanded Medicaid eligibility, premium rating restrictions in the nongroup, or individual, and small-group markets, minimum medical loss ratios (MLRs)—have long been features of New York’s broad public health insurance programs and highly regulated health insurance market. Once the ACA became law, there was little doubt that New York would embrace reform. Yet, partisan gridlock in Albany has made for a rough road to health reform for New York. After many months of wrangling with the state Legislature, Gov. Andrew Cuomo (D) resorted to authorizing the state health insurance exchange by executive order in 2012, giving New York’s exchange a later start than in many states.

t first glance, New York and the Long Island metropolitan area appear well positioned for smooth implementation of the federal Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010, according to a new Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC) study of Long Island’s commercial and Medicaid insurance markets (see Data Source). Key ACA reforms—expanded Medicaid eligibility, premium rating restrictions in the nongroup, or individual, and small-group markets, minimum medical loss ratios (MLRs)—have long been features of New York’s broad public health insurance programs and highly regulated health insurance market. Once the ACA became law, there was little doubt that New York would embrace reform. Yet, partisan gridlock in Albany has made for a rough road to health reform for New York. After many months of wrangling with the state Legislature, Gov. Andrew Cuomo (D) resorted to authorizing the state health insurance exchange by executive order in 2012, giving New York’s exchange a later start than in many states.

Another threat to successful implementation is the state’s commitment to stringent insurance regulations that exceed ACA requirements, most notably in small-group and nongroup community rating. Most respondents expected stricter state regulations to keep New York nongroup premiums very high and lead many healthier state residents to continue staying out of the nongroup risk pool. However, when 2014 premiums were released in July, the approved rates were lower than most had expected. What remains uncertain is how sustainable these rates will be over time—specifically, whether they will remain sufficiently low to attract and retain a sizable pool of younger, healthier enrollees. Key factors likely to influence how national health reform plays out in the Long Island health care market include:

Market Background

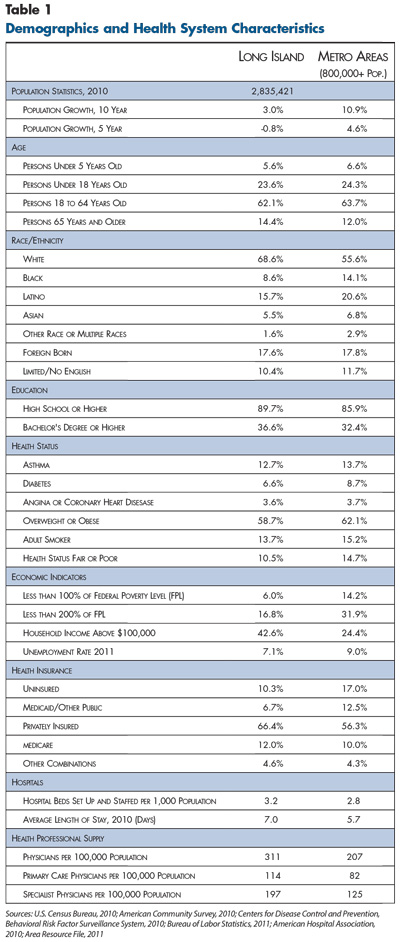

![]() he metropolitan area of Nassau and Suffolk counties in eastern New York—collectively known as Long Island—is home to 2.8 million people.1 The two counties have populations of roughly equal size, but Suffolk County has more than double the land area and is more rural than Nassau County (see map). Over the last decade, the region’s population growth has been much slower than the nationwide metropolitan average (3% vs. 11%) and even contracted slightly between 2005 and 2010 (see Table 1).

he metropolitan area of Nassau and Suffolk counties in eastern New York—collectively known as Long Island—is home to 2.8 million people.1 The two counties have populations of roughly equal size, but Suffolk County has more than double the land area and is more rural than Nassau County (see map). Over the last decade, the region’s population growth has been much slower than the nationwide metropolitan average (3% vs. 11%) and even contracted slightly between 2005 and 2010 (see Table 1).

Long Island stands out from other large metropolitan areas on a number of dimensions. Nassau and Suffolk are among the wealthiest counties in the United States. Forty-three percent of households have annual incomes above $100,000, compared to 24 percent on average nationwide, and only 6 percent of individuals live below the poverty level, compared to 14 percent nationwide. However, the area’s high cost of living means that federal poverty indicators may overstate the affluence and fail to capture the proportion of residents struggling economically.

Long Island residents on average also have higher education levels, more insurance coverage and more favorable health status than other metropolitan residents. They also tend to be older and less racially/ethnically diverse, despite a doubling of the minority population since 1990.2

The Long Island economy weathered the Great Recession better than the rest of the state and most metropolitan areas nationwide. The area’s unemployment rate remained below the nationwide metropolitan average and increased by a smaller magnitude between 2007 and 2011 (3.8% to 7.1% in Long Island vs. 4.5% to 9.0% nationwide). Nevertheless, the economic downturn—particularly in the financial sector—did have a serious impact on Long Island, since many residents, especially in Nassau County, commute to high-wage jobs in New York City.

Apart from the New York City economy, however, the Long Island region has a distinct economic base. In past decades, the economy was anchored by large aerospace and defense companies. With the Long Island presence of these industries having declined since the 1980s, the region’s economy has diversified, with small firms increasingly accounting for a larger share of employment. These small firms span a wide range of industries, including agriculture, health care, technology and professional services. Today, the region increasingly attracts reverse commuters from New York City, including lower-wage workers seeking employment in the region’s burgeoning service sector.

State Regulatory Background

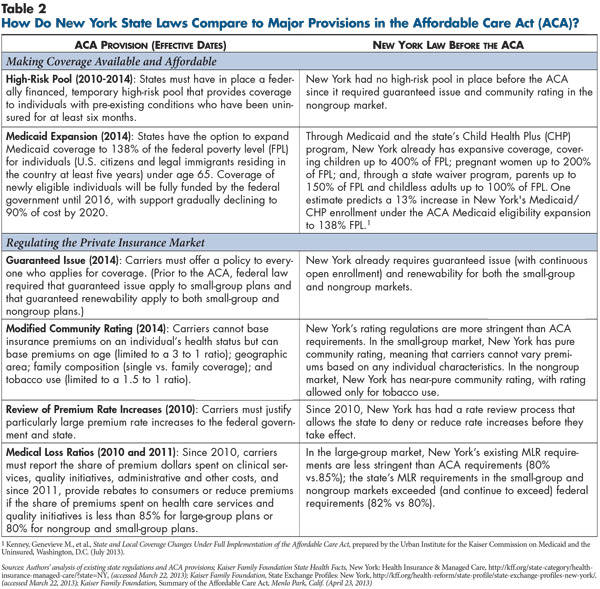

![]() n the early 1990s, New York was among a group of trailblazing states that enacted nongroup and small-group health insurance market reforms. Even among that group of states, New York stood out for implementing the most stringent regulations, and New York’s health insurance market today remains one of the country’s most tightly regulated, with some requirements exceeding new ACA standards (see Table 2). New York is the only state that requires pure community rating in the small-group market (2-50 employees), meaning that premiums cannot vary by any individual risk characteristics. The nongroup market has nearly pure community rating, allowing rates to vary only by tobacco use. Guaranteed issue with continuous open enrollment and guaranteed renewability apply in both markets, meaning that those seeking insurance must be offered coverage at any time—not just during an annual open-enrollment period—and they must be permitted to renew their policies.

n the early 1990s, New York was among a group of trailblazing states that enacted nongroup and small-group health insurance market reforms. Even among that group of states, New York stood out for implementing the most stringent regulations, and New York’s health insurance market today remains one of the country’s most tightly regulated, with some requirements exceeding new ACA standards (see Table 2). New York is the only state that requires pure community rating in the small-group market (2-50 employees), meaning that premiums cannot vary by any individual risk characteristics. The nongroup market has nearly pure community rating, allowing rates to vary only by tobacco use. Guaranteed issue with continuous open enrollment and guaranteed renewability apply in both markets, meaning that those seeking insurance must be offered coverage at any time—not just during an annual open-enrollment period—and they must be permitted to renew their policies.

A 2010 New York law gave the state Division of Financial Services, which regulates insurance, the authority to review and approve premium rate increases in the nongroup and small-group markets.3 New York has been among the most aggressive states in enforcing its prior-approval authority, ranking second among all states in the percentage of rate filings that were disapproved, withdrawn or resulted in lower-than-proposed rates, according to a 2011 federal government study.4 The same state law imposed medical loss ratio (MLR) requirements slightly more stringent than the ACA’s (82% vs. 80% for the small-group and nongroup markets).

The number of mandated benefits in New York’s individual and small-group markets is not high relative to other states. However, New York’s small-group mandates include some of the most costly services, such as mental health parity and comprehensive autism treatment.

In the nongroup market, New York’s guaranteed-issue requirement and rating restrictions led to a “death spiral” during the 1990s, as soaring premiums led the relatively young and healthy, and then most enrollees, to drop coverage. By 2012, the nongroup market had contracted to the point where statewide enrollment totaled less than 20,000 (0.1% of the population). Product offerings are limited to HMO products, which are available only because a state law requires HMOs to offer products in the nongroup market.5 Premiums now commonly exceed $50,000 annually for an HMO policy for a Long Island family.6 In effect, New York’s nongroup market has been functioning as a nonsubsidized high-risk pool, providing coverage mainly to the sickest state residents. New York did not operate its own high-risk pool until the ACA required states to set up temporary high-risk pools in 2010.7

To bolster the faltering nongroup market, New York established the Healthy NY program in 2000. Healthy NY is a state-subsidized insurance product that offers a less-comprehensive benefit package to certain categories of state residents, including self-employed people and uninsured workers with low to moderate incomes whose employers do not offer coverage. Since 2010, new enrollees in the program have been limited to a high-deductible option to mitigate premium increases. In September 2012, Healthy NY enrollment totaled approximately 174,000 people statewide. Beginning in January 2014, Healthy NY will no longer be offered to individuals or sole proprietors, who will instead be directed to the state exchange. The program will still be available for small employers under current eligibility rules, with revised coverage to meet ACA requirements for covered benefits and gold-level standards for actuarial value.

Broad and Deep Medicaid Program

![]() ot only are New York’s Medicaid eligibility standards among the most expansive in the country, the state’s Medicaid benefits also are among the most comprehensive offered. The state’s Child Health Plus (CHP) program—a pioneer program that served as the blueprint for national implementation of the state Children’s Health Insurance Program in the 1990s—covers uninsured children, with subsidies available for families with incomes above Medicaid thresholds but lower than 400 percent of poverty. Using only state funds, CHP also covers children ineligible for Medicaid because of immigration status.

ot only are New York’s Medicaid eligibility standards among the most expansive in the country, the state’s Medicaid benefits also are among the most comprehensive offered. The state’s Child Health Plus (CHP) program—a pioneer program that served as the blueprint for national implementation of the state Children’s Health Insurance Program in the 1990s—covers uninsured children, with subsidies available for families with incomes above Medicaid thresholds but lower than 400 percent of poverty. Using only state funds, CHP also covers children ineligible for Medicaid because of immigration status.

Since 2001, New York’s Family Health Plus program has covered childless adults up to 100 percent of poverty and parents up to 150 percent with a limited benefit package. Consequently, the newly eligible Medicaid population under the ACA expansion is expected to be small—about 100,000 statewide. However, a much larger population—about 1 million people statewide—is currently eligible for Medicaid but not enrolled. In March 2013, New York signaled its intention to move forward with ACA Medicaid expansion by approving a budget for fiscal year 2013-14 that revises the program’s income eligibility thresholds to align with ACA standards.

The New York Medicaid program has a long history of facilitating enrollment and renewal for targeted groups. Since the 1990s, pregnant women and CHP children have been granted presumptive eligibility,8 and CHP children have been allowed to apply by mail rather than in person. In 2008, the state began extending presumptive eligibility to Medicaid children and eliminating in-person interviews for pregnant women. And, by 2015 New York will replace its current county-based enrollment and renewal systems with a single statewide system to improve efficiency and simplify interaction with the state exchange.

In January 2011, state budget constraints and pressures from an already costly Medicaid program led the governor to establish a Medicaid Redesign Team (MRT) to convene stakeholders with the stated objectives of reducing costs while improving quality and efficiency. Redesign efforts have focused on traditional cost-containment strategies, such as benefit restrictions and cost-sharing increases, while emphasizing medical homes for high-cost enrollees and managed care for all. Since the early 1990s, New York had moved most Medicaid enrollees into managed care under federal waivers.9 Under the MRT initiative, the state tightened exemptions and exclusions so that the only groups remaining in fee-for-service Medicaid are those receiving long-term care and those with developmental disabilities. The state also has been eliminating fee-for-service carve-outs for pharmacy, personal care, and mental health and substance abuse treatment, and transitioning these services to managed care contracts.

The redesign program also instituted global state Medicaid spending caps; if spending exceeds the cap, the state health commissioner has the authority to cut programs.10 In 2012, the MRT estimated that its initiatives had saved $2.3 billion since implementation. In August 2012, the state requested an additional federal waiver to retain $10 billion in current and expected savings to continue redesign efforts, and the waiver request is pending.

Commercial Insurance Market Lacks Competition

![]() arket observers reported little competition in the Long Island commercial health insurance market. Since the 1990s, some health plans have consolidated, while others went out of business. The major players in the commercial market are UnitedHealth Group, which primarily offers large-group products through UnitedHealthcare and small-group products through Oxford Health Plan; Empire Blue Cross and Blue Shield, a WellPoint subsidiary; Aetna; and EmblemHealth, a regional plan formed from a merger of Group Health Inc. and the Health Insurance Plan (HIP) of Greater New York.11 Emblem, with a much more limited presence on Long Island than in its historical stronghold of New York City, is widely regarded as the “blue-collar plan,” with less brand appeal to purchasers and consumers, especially higher-wage earners.

arket observers reported little competition in the Long Island commercial health insurance market. Since the 1990s, some health plans have consolidated, while others went out of business. The major players in the commercial market are UnitedHealth Group, which primarily offers large-group products through UnitedHealthcare and small-group products through Oxford Health Plan; Empire Blue Cross and Blue Shield, a WellPoint subsidiary; Aetna; and EmblemHealth, a regional plan formed from a merger of Group Health Inc. and the Health Insurance Plan (HIP) of Greater New York.11 Emblem, with a much more limited presence on Long Island than in its historical stronghold of New York City, is widely regarded as the “blue-collar plan,” with less brand appeal to purchasers and consumers, especially higher-wage earners.

Oxford is the dominant carrier in the small-group space. Many insurance brokers in the market provide small-group rate quotes only for Oxford policies. Until 2013, Empire had been the second-largest carrier, but it dramatically reduced product offerings for 2013 and lost significant membership. Empire cited the state insurance department’s denials of proposed premium increases as the primary driver behind the company’s withdrawal from the small-group segment. Empire was required by the state to continue offering some products for an additional year to give more notice to policyholders.

Employers in New York and Long Island are somewhat more likely to be fully insured than employers in similar-sized markets elsewhere. The reasons are not entirely clear, since the extent of state regulation would be expected to make self-insurance more attractive to employers. Some respondents suggested that the relatively low prevalence of self-insurance reflects a risk-averse culture among employers, while others noted that benefits consultants have not been as aggressive in pushing self-insurance in this market as they have elsewhere.

Long Island employers historically have provided relatively comprehensive health benefits, but as in other markets nationwide, financial pressures in recent years have prompted employers to increase employee premium contributions and out-of-pocket cost sharing. Most Long Island employers, even small firms, still tend to offer employees a choice among two or three insurance products. Preferred provider organizations (PPO) products are the most popular commercial offerings in the market, followed by exclusive provider organization (EPO) products, which are similar to HMOs in providing only in-network coverage, but are more akin to PPOs on other dimensions. EPO products are written on an insurance license rather than an HMO license, allowing more flexibility in benefit design, including cost-sharing requirements. Indeed, some EPO products have very high out-of-pocket costs for certain services, such as inpatient care. Like PPOs, EPOs feature broad provider networks and do not use primary care gatekeeping.

High-deductible health plans (HDHPs) have not gained significant traction in the market, and employers that do adopt HDHPs typically offer them as an option alongside an EPO and/or PPO product, rather than replacing conventional products altogether. Brokers and health plans estimated that 10 percent to 20 percent of small-group enrollees are currently in high-deductible products—a substantially lower rate than in many markets.

Broad provider networks have long been the norm for Long Island’s commercial products, but the market has recently begun to see some experimentation with limited-network products. The most prominent is a collaboration between UnitedHealthcare and North Shore-LIJ Health System. Introduced in 2012, the UnitedHealthcare North Shore-LIJ Advantage product features a tiered-provider network, with the preferred tier—requiring the lowest patient cost sharing—consisting of North Shore-LIJ hospitals and physicians. The product has not gained significant enrollment, in large part, because the premium savings relative to full-network products are not substantial. Some respondents noted that because North Shore-LIJ is not a low-cost provider, any limited networks built around the system would be likely to yield premium savings only if the system is willing to make substantial rate concessions.

Empire is planning to roll out a narrow network, which purchasers will be able to use with any commercial product. The narrow network is built around Empire’s new patient-centered primary care physician (PCP) program, in which select in-network PCPs manage Empire enrollees in exchange for an additional care management fee. Respondents noted that other health plans and providers also are exploring potential limited-network collaborations. While the collaborations do not appear to involve any risk sharing between insurers and providers to date, some market observers suggested the market is moving inevitably in that direction. However, it is unclear how prepared most providers are to assume financial risk in a market where fee-for-service payments have long been the norm for commercial contracts.

Consolidated Hospital Market

![]() he hospital market on Long Island is highly consolidated, with most independent hospitals joining one of the two large systems: North Shore-LIJ Health System (15 hospitals total, 10 on Long Island) and Long Island Health Network (10 hospitals, all on Long Island). North Shore-LIJ is considered to have the stronger brand from the perspective of purchasers and consumers and more negotiating leverage with insurers.

he hospital market on Long Island is highly consolidated, with most independent hospitals joining one of the two large systems: North Shore-LIJ Health System (15 hospitals total, 10 on Long Island) and Long Island Health Network (10 hospitals, all on Long Island). North Shore-LIJ is considered to have the stronger brand from the perspective of purchasers and consumers and more negotiating leverage with insurers.

Only two major acute-care hospitals do not belong to either of these systems: Stony Brook University Hospital, part of the State University of New York and Suffolk County’s only Level 1 trauma center; and Nassau University Medical Center,12 a financially struggling public safety net hospital that recently downsized inpatient capacity and reportedly is seeking a closer affiliation with North Shore-LIJ. Additionally, there are several small hospitals in eastern Suffolk County that have affiliated.

A fair number of Long Island physicians are employed by hospitals, with North Shore-LIJ (2,500 physicians) and Stony Brook University (700 physicians) standing out as the top employers. However, many physicians remain in small, independent practices in the Long Island market.

Booming Medicaid Managed Care Market

![]() n sharp contrast to the lack of health plan participation and competition in the small-group and nongroup segments of commercial insurance, Long Island’s Medicaid sector offers what one respondent termed a “fruitful market” for managed care plans. From 2008 to 2012, the Medicaid managed care population more than doubled in Nassau and Suffolk counties. More than half a dozen plans competed for the 222,000 Medicaid enrollees in these two counties in 2012. In 2012, the percentage of Long Island residents covered by Medicaid reached 13.1 percent—a significant increase from 8.1 percent in 2008—though it was only half of the statewide proportion of residents receiving Medicaid (26.0%) thanks to Long Island’s affluence.13

n sharp contrast to the lack of health plan participation and competition in the small-group and nongroup segments of commercial insurance, Long Island’s Medicaid sector offers what one respondent termed a “fruitful market” for managed care plans. From 2008 to 2012, the Medicaid managed care population more than doubled in Nassau and Suffolk counties. More than half a dozen plans competed for the 222,000 Medicaid enrollees in these two counties in 2012. In 2012, the percentage of Long Island residents covered by Medicaid reached 13.1 percent—a significant increase from 8.1 percent in 2008—though it was only half of the statewide proportion of residents receiving Medicaid (26.0%) thanks to Long Island’s affluence.13

Long Island’s Medicaid managed care market is composed of a mix of local nonprofit plans and national for-profit plans. United and WellPoint both offer Medicaid plans through subsidiaries: AmeriChoice, also known as UnitedHealthcare Community Plan, and Amerigroup, respectively. Local nonprofit plans include HealthFirst, Affinity, Fidelis Care and HIP of Greater New York (a subsidiary of EmblemHealth). Empire does not participate in Medicaid but does offer Child Health Plus products. Mergers and acquisitions over the last decade have reduced the number of competing Medicaid plans slightly, but the market is thriving compared to the commercial small-group market.

Medicaid enrollees’ access to Long Island physicians and hospitals is generally considered good. The state Department of Health surveys enrollees every two years to gauge their access to providers and requires plans to report quarterly on the breadth and adequacy of their provider networks. While overall access is good, problems reportedly persist in the sparsely populated eastern portion of Suffolk County, and some types of specialists, such as child psychiatrists, are chronically scarce throughout the region. The Department of Health surveys also gauge other aspects of plan performance, including outcomes and process measures, and compare the performance of each plan against national benchmarks. Overall, Long Island Medicaid plans have consistently outperformed national benchmarks.14

To manage health care costs, Medicaid plans use many traditional managed-care strategies, including primary care gatekeeping, limited-provider networks and prior-authorization requirements. Several plans pay primary care physicians capitated rates—fixed per-member, per-month amounts—for primary care services, rather than separate fees for each visit or service. And, at least one Medicaid plan—provider-sponsored HealthFirst—assigns enrollees to primary care physicians who are, in turn, affiliated with one of the hospitals in the plan’s network. Those hospitals are then assigned a spending target based on their enrollees and have taken on both upside and downside financial risk for patient care. Although this arrangement is similar to Medicare accountable care organizations, it takes a more aggressive approach in shifting risk to the provider. Largely because the hospitals assume financial risk, they work jointly with the health plan to identify opportunities for reducing readmissions.

Lurching Toward Reform

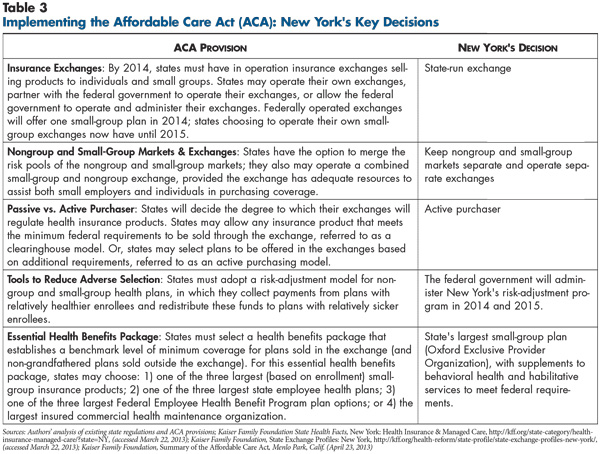

![]() t first glance, the state—and by extension, Long Island—seems well positioned to implement health reform (see Table 3). As previously noted, New York already had implemented many of the key elements of health reform well before the ACA was enacted, including expanded Medicaid eligibility, insurer medical-loss-ratio requirements, and rating restrictions and premium prior-approvals in the small-group and nongroup markets. These provisions place New York well ahead of most states on the path to ACA compliance.

t first glance, the state—and by extension, Long Island—seems well positioned to implement health reform (see Table 3). As previously noted, New York already had implemented many of the key elements of health reform well before the ACA was enacted, including expanded Medicaid eligibility, insurer medical-loss-ratio requirements, and rating restrictions and premium prior-approvals in the small-group and nongroup markets. These provisions place New York well ahead of most states on the path to ACA compliance.

Nevertheless, political infighting within state government has made the road to health reform a rough one. While there was little doubt that New York would establish its own health insurance exchange, the Republican-led state Senate managed to halt legislation in 2011 that would have established an exchange. After months of wrangling with lawmakers, Gov. Cuomo abandoned the legislative route, resorting instead to an executive order to establish the exchange in April 2012 within the Department of Health. The result was that the exchange got off to a late start and had less legitimacy in the eyes of some stakeholders. Compounding the problem of the exchange’s late start has been what many respondents perceived as the exchange board’s unwillingness to seek adequate input from stakeholders on the design and operation of the exchange, as well as a perceived failure to communicate timely decisions to stakeholders. As a result, some respondents expressed pessimism about the ability of the New York exchange to perform necessary functions and meet federal deadlines.

Another barrier to smooth health reform implementation has been the apparent commitment of state government to earlier policy decisions inconsistent with the ACA. As noted earlier, New York’s rating restrictions in the small-group and nongroup markets have long exceeded ACA requirements. In the nongroup market in particular, there has been evidence that guaranteed-issue and near-pure community rating have destabilized and contracted the market. In fact, the policy makers responsible for the ACA drew on the New York nongroup lesson in making two key policy decisions. The first was not to require pure community rating in the nongroup market but rather to allow premiums to vary with age, up to a 3-to-1 ratio. The second was the individual mandate requiring almost all to have coverage and penalizing those who remain uninsured.

With the ACA permitting states to retain regulations that exceed federal requirements, respondents suggested that New York would be unlikely to relax its near-pure community rating requirement in the nongroup market. One broker, for example, expressed “99.9 percent [certainty that state policy makers] will not relax their rating restrictions,” observing that “New York State has always taken pride that they have stronger rules than the federal government,” even if these stronger rules have yielded dysfunctional markets.

New York’s current nongroup market is very small and contains mostly very sick people paying hefty premiums. Under the ACA, exchange subsidies and the individual mandate together are expected to add healthier people to the nongroup risk pool, thus lowering projected premiums in the nongroup market.15 These expectations were indeed borne out when 2014 premiums were released in July 2013. Rates for individual coverage under a bronze-level policy on the exchange ranged from $285 to $548 per month.16 While these rates are for new products that are not directly comparable to existing offerings in the nongroup market, they represent substantial price reductions from the current monthly range of $1,001 to $3,319.17 New entrants to the Long Island commercial market—Fidelis Care, previously a Medicaid-only plan, and Freelancers Co-Op, a nonprofit plan that represents independent workers nationwide—submitted the lowest rates, likely as part of a strategy to gain market share. In contrast, approved rates for national giants United and Aetna were the highest among exchange products.18

The 2014 premiums are significantly lower than most respondents had expected and have been portrayed in the media as a promising development.19 They also are not out of line with the rates released by other states to date.20 However, it remains to be seen how stable and sustainable New York’s premiums will remain over time. This will depend largely on the ability of the nongroup market to attract and retain enough younger, healthier enrollees to sustain a viable risk pool. Achieving this goal is more challenging given New York’s stricter rating rules. If rates spiral upward, it is uncertain whether individual-mandate penalties will be high enough to keep healthier individuals in the risk pool. Paradoxically, New York’s legacy of aggressive health insurance regulation may work against the viability of health reform.

Commercial plans tiptoe and Medicaid plans jump into the exchange. Several local Medicaid plans intend to offer products for the Long Island market on the individual exchange. Plan executives cited “churn” as a key reason to participate in the exchange—that is, they are aiming to retain enrollees as their incomes fluctuate above and below the cutoffs separating eligibility for Medicaid and the exchange subsidies. Although these plans see opportunities for enrollment growth in the exchanges, they also expect challenges to entering a new competitive arena and going head-to-head for the first time with commercial plans.

In contrast to the tempered enthusiasm of the Medicaid plans, commercial plans are proceeding much more cautiously in deciding whether to offer products for the Long Island market on the exchange. Oxford dominates the region’s small-group market and plans to participate in the small-group exchange; its sister company United Healthcare will participate in the nongroup exchange. No other established mainstream commercial insurers submitted bids to the state for small-group exchange products. Two new entrants did submit bids: Freelancers Co-Op and North Shore-LIJ, the market’s dominant provider system making its first foray as a commercial insurer. Among the three plans, Freelancers is positioning itself as the low-cost option, with a bronze-level premium of $340 per month for small-group coverage, while North Shore-LIJ’s rate is comparable to Oxford’s ($467 vs. $474 per month).21

Brokers face uncertain future. As in the rest of New York, the vast majority of Long Island small-group insurance policies currently are purchased through brokers, who both sell the policies and commonly perform for small employers many services typically provided by in-house human resources departments in larger companies. In contrast to some states where nongroup sales represent a significant line of business, the long-ago collapse of New York’s nongroup market means that New York brokers’ health insurance business relies almost entirely on group sales. Brokers have seen their commissions shrink over time, as insurers progressively clamped down on administrative costs to meet New York’s MLR requirements.

The advent of health reform brings both opportunities and threats to Long Island brokers. They perceive a growing need for their services, given the new coverage options and subsidies, as well as new requirements facing employers and employees. And, the exchange will give brokers the opportunity to take an active role in enrolling and providing services to individuals and employers purchasing exchange products.22 The exchange has announced it will not set or cap broker commissions; however, it was widely expected that insurers would continue squeezing broker commissions, given the pressures that insurers themselves will face in the state rate review process and on the exchange. Perhaps the biggest threat to brokers is the vision of the exchange succeeding as a marketplace directly connecting health plans and consumers, bypassing brokers and their commissions altogether. As a result, Long Island brokers generally regarded their own prospects in health insurance lines of business as bleak and already had begun to diversify into other areas.

Health insurance expansion population expected to be small. As previously noted, New York’s Medicaid program already has generous eligibility standards, and Long Island’s affluent residents enjoy high rates of private insurance coverage. As a result, the number of people expected to gain health insurance coverage under national health care reform is expected to be much lower than in most communities. The modest insurance expansions are not expected to trigger shortages in primary care or other provider capacity on Long Island, especially in light of the region’s abundant provider supply.

Issues to Track

Notes

Data Source

As part of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s (RWJF) State Health Reform Assistance Network initiative, the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC) examined commercial and Medicaid health insurance markets in eight U.S. metropolitan areas: Baltimore; Portland, Ore.; Denver; Long Island, N.Y.; Minneapolis/St. Paul; Birmingham, Ala.; Richmond, Va.; and Albuquerque, N.M. The study examined both how these markets function currently and are changing over time, especially in preparation for national health reform as outlined under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010. In particular, the study included a focus on the impact of state regulation on insurance markets, commercial health plans’ market positions and product designs, factors contributing to employers’ and other purchasers’ decisions about health insurance, and Medicaid/state Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) outreach/enrollment strategies and managed care. The study also provides early insights on the impact of new insurance regulations, plan participation in health insurance exchanges, and potential changes in the types, levels and costs of insurance coverage.

This primarily qualitative study consisted of interviews with commercial health plan executives, brokers and benefits consultants, Medicaid health plan executives, Medicaid/CHIP outreach organizations, and other respondents—for example, academics and consultants—with a vantage perspective of the commercial or Medicaid market. Researchers conducted 16 interviews in the Long Island market between December 2012 and March 2013. Additionally, the study incorporated quantitative data to illustrate how the Long Island market compares to the other study markets and the nation. In addition to a Community Report on each of the eight markets, key findings from the eight sites will also be analyzed in two publications, one on commercial insurance markets and the other on Medicaid managed care.