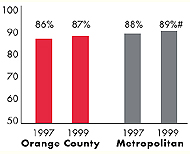

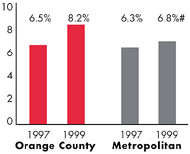

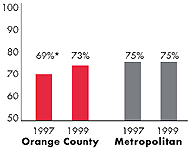

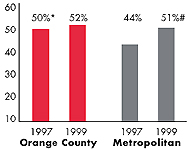

* Site value is significantly different from the mean for metropolitan

areas over 200,000 population.

# Statistically significant difference between 1997 and 1999 at p< .05.

The information in these graphs comes from the Household and Physician

Surveys conducted in 1996-1997 and 1998-1999 as part of HSC’s Community

Tracking Study.