Issue Brief No. 46

December 2001

James D. Reschovsky, Jack Hadley

![]() tate and local efforts to reduce the number of uninsured workers include three

major approaches: public insurance expansions, subsidies paid directly to low-income

workers to help pay their share of employer-sponsored insurance premiums or

buy individual insurance and subsidies paid directly to small employers to reduce

the cost of health insurance premiums. Based on a national study by the Center

for Studying Health System Change (HSC), premium subsidies paid directly to

small firms are unlikely to significantly reduce the number of uninsured. About

16 million people work in firms with fewer than 50 workers that do not offer

health insurance. A hypothetical 30 percent premium subsidy targeted to the

employers of these workers—slightly more generous than the average in existing

small firm subsidy programs across the country—would extend coverage to only

about half a million uninsured workers if implemented nationally.

tate and local efforts to reduce the number of uninsured workers include three

major approaches: public insurance expansions, subsidies paid directly to low-income

workers to help pay their share of employer-sponsored insurance premiums or

buy individual insurance and subsidies paid directly to small employers to reduce

the cost of health insurance premiums. Based on a national study by the Center

for Studying Health System Change (HSC), premium subsidies paid directly to

small firms are unlikely to significantly reduce the number of uninsured. About

16 million people work in firms with fewer than 50 workers that do not offer

health insurance. A hypothetical 30 percent premium subsidy targeted to the

employers of these workers—slightly more generous than the average in existing

small firm subsidy programs across the country—would extend coverage to only

about half a million uninsured workers if implemented nationally.

![]() olicy makers are exploring ways to extend health insurance

coverage to the working uninsured-a good target since nearly 75 percent of the

uninsured live in families with at least one full-time worker, many of whom work

in small firms. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, an estimated 38.7 million

Americans were uninsured in 2000. While the Bush Administration has proposed subsidies

in the form of tax credits for people buying individual insurance, and several

states have initiated Medicaid waiver programs to expand public coverage to low-income,

uninsured workers, another approach is to build on the employer-sponsored insurance

system. To this end, several states have funded programs to subsidize low-income

workers’ contributions to their employers’ health coverage.1

olicy makers are exploring ways to extend health insurance

coverage to the working uninsured-a good target since nearly 75 percent of the

uninsured live in families with at least one full-time worker, many of whom work

in small firms. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, an estimated 38.7 million

Americans were uninsured in 2000. While the Bush Administration has proposed subsidies

in the form of tax credits for people buying individual insurance, and several

states have initiated Medicaid waiver programs to expand public coverage to low-income,

uninsured workers, another approach is to build on the employer-sponsored insurance

system. To this end, several states have funded programs to subsidize low-income

workers’ contributions to their employers’ health coverage.1

Yet, two in five uninsured workers and about two-thirds of low-income uninsured workers with family incomes less than 200 percent of poverty-or about $35,000 a year for a family of four in 2001-work in firms that do not offer coverage. To address this, several states and local communities are encouraging small employers to offer health insurance by subsidizing premiums. State initiatives include the Kansas Small Employer Tax Credit, Massachusetts’ Insurance Partnership Program and Healthy New York. Local initiatives, often funded by private foundations or federal disproportionate share hospital payments, are underway in Denver; New York; Muskegon, Mich.; San Diego; and Wayne County, Mich.2

The programs vary in size with enrollment typically limited by available funding. The number of firms taking subsidies ranges from fewer than 50 in some programs to more than 2,000. Subsidy amounts vary appreciably and, in some cases, differ by a firm’s profitability or workforce characteristics. A 30 percent subsidy- slightly above the midpoint-would reduce the cost of an average policy offered by small firms with fewer than 50 workers for single coverage from $2,732 to $1,912 and for family coverage from $6,434 to $4,504.3

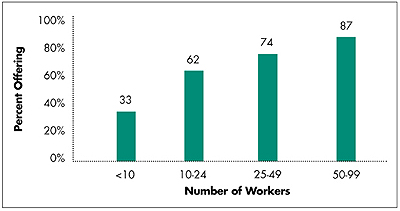

Since nearly all employers with more than 100 workers offer health insurance benefits, while less than half of smaller employers do, virtually all state and local employer health insurance subsidy programs are targeted at small firms, typically those with fewer than 50 workers not currently offering coverage. Even among small employers, size matters: Only one-third of firms employing fewer than 10 workers offer health insurance (see Figure 1).

| Figure 1 Percent of Employers Offering Health Insurance by Firm Size, 1997

Source: 1997 Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Employer Health Insurance Survey |

![]() fforts to increase health insurance coverage by subsidizing

premiums for small firms are unlikely to be fruitful, according to HSC research.

Large subsidies are needed to increase coverage by even modest amounts.4

For example, among all firms with fewer than 50 workers, only 40 percent offer

health insurance. It would take a 30 percent reduction in premium costs to increase

the proportion of those offering insurance by only 15 percent, from 40 percent

to 46 percent.

fforts to increase health insurance coverage by subsidizing

premiums for small firms are unlikely to be fruitful, according to HSC research.

Large subsidies are needed to increase coverage by even modest amounts.4

For example, among all firms with fewer than 50 workers, only 40 percent offer

health insurance. It would take a 30 percent reduction in premium costs to increase

the proportion of those offering insurance by only 15 percent, from 40 percent

to 46 percent.

Understanding why small employers are less likely to offer health insurance helps explain why they are unlikely to be particularly responsive to premium subsidies. Two factors are central:

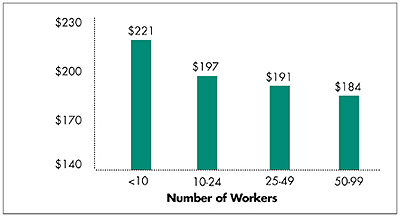

Higher Costs. The higher costs small employers face are the result of both higher insurance premiums and per-employee costs associated with searching for and administering a health plan. For instance, a hypothetical health maintenance organization (HMO) plan with minimum benefits would have monthly premiums for single coverage that are $37 more for employers with fewer than 10 workers than for employers with 50-99 workers (see Figure 2). Small employers face higher insurance premiums for several reasons. First, insurers’ costs for marketing and administration must be spread over fewer enrollees. Second, costs of insuring small groups may be greater because of adverse selection-which occurs when employers whose workers have above-average health care needs are more likely to seek coverage or purchase more comprehensive coverage. Finally, small employers lack the bargaining power of larger employers in negotiating with insurers.

Low-Income Employees. Twenty-eight percent of people working for small employers are classified as low income, compared with 19 percent of people working for larger employers. Low-income workers are less willing to buy health insurance, partly because it is too costly, but also because they are more likely to have access to public insurance or free or reduced-cost care through safety net providers. As a result, small employers are less likely to need to offer health insurance benefits as a way to attract and retain workers.

Other Factors. In addition to premium costs and worker income, other factors influence employer decisions to offer health insurance, including the proportion of employees who work part time, availability of public health insurance and free or reduced-cost care at clinics and hospitals, and the tightness of the local labor market, which also influences whether an offer of health insurance is needed to attract and retain labor.

| Figure 2 Predicted Monthly Premiums for a Minimum-Benefit HMO Policy by Firm Size, 2001

Note: Values are predicted from a statistical model accounting for the differences in premiums for firms that do and do not offer insurance. Numbers inflated to reflect 2001 values based on the 1998 KPMG Survey of Employer-Sponsored Health Benefits and the 2001 Kaiser Family Foundation/Health Research and Educational Trust (KFF/HRET) Employer Health Benefits Survey. Source: 1997 Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Employer Health Insurance Survey |

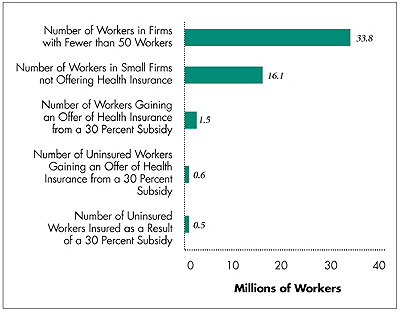

![]() hile a 30 percent premium subsidy would increase the proportion

of small employers offering insurance by only 15 percent, the impact on the number

of workers would be just over half as large.5 And,

the impact on the number of uninsured would actually be much smaller, with less

than 3 percent of workers in nonoffering firms with fewer than 50 workers actually

obtaining insurance as a result of the subsidy. Nationally, firms with fewer than

50 people employ nearly 34 million workers, about 16 million of whom-48 percent-are

not offered health insurance. Under a 30 percent premium subsidy hypothetically

available to all nonoffering firms, 1.5 million workers would gain offers of employer-sponsored

coverage, reducing the number of workers who lack coverage offers to 14.6 million

(see Figure 3).

hile a 30 percent premium subsidy would increase the proportion

of small employers offering insurance by only 15 percent, the impact on the number

of workers would be just over half as large.5 And,

the impact on the number of uninsured would actually be much smaller, with less

than 3 percent of workers in nonoffering firms with fewer than 50 workers actually

obtaining insurance as a result of the subsidy. Nationally, firms with fewer than

50 people employ nearly 34 million workers, about 16 million of whom-48 percent-are

not offered health insurance. Under a 30 percent premium subsidy hypothetically

available to all nonoffering firms, 1.5 million workers would gain offers of employer-sponsored

coverage, reducing the number of workers who lack coverage offers to 14.6 million

(see Figure 3).

| Figure 3 Impact of a 30 Percent Employer Premium Subsidy on Workers in Small Firms

Source: Analysis of the 1997 Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Employer Health Insurance Survey and HSC Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1998-99 |

Since 59 percent of workers in firms with fewer than 50 workers have alternative sources of health insurance-mostly through their spouse or public insurance- the number of uninsured workers who would actually gain offers of insurance would only increase by about 600,000. In addition, not all uninsured workers will opt to take up coverage. Other HSC research indicates that about one in five low-income workers fails to take up offered coverage, so the impact on the number of uninsured workers would be even more modest-about half a million workers.6 The bottom line: about 3 percent of small firm workers without offers of health insurance would gain coverage as a result of a 30 percent premium subsidy program targeted at employers with fewer than 50 workers that previously had not offered coverage.

If subsidies are extended to firms that offer health insurance-something programs seldom do now-some portion of the subsidies would likely be passed on to workers in the form of lower premium sharing or higher wages, prompting additional workers to take up coverage. While the impact of this on the number of uninsured persons will be quite modest, it would be expensive, since nearly all eligible firms offering health insurance are likely to take advantage of such a subsidy. Failure to extend subsidies to firms that offer insurance raises an equity issue, however, because equally deserving employers that have been providing health benefits to their workers are not eligible to benefit from the subsidy.

![]() irect subsidies of employer-sponsored insurance premiums suffer

from two fundamental problems. First, their success in extending health insurance

to additional workers is hindered by small employers’ relatively low responsiveness

to premium subsidies. Subsidies would have to be very large to have a significant

effect on the number of uninsured workers who gain access to employer-sponsored

health benefits. Second, because subsidies are given to the employer-rather than

directly to employees-it is difficult to target the subsidies to those most in

need: low-income, uninsured persons.

irect subsidies of employer-sponsored insurance premiums suffer

from two fundamental problems. First, their success in extending health insurance

to additional workers is hindered by small employers’ relatively low responsiveness

to premium subsidies. Subsidies would have to be very large to have a significant

effect on the number of uninsured workers who gain access to employer-sponsored

health benefits. Second, because subsidies are given to the employer-rather than

directly to employees-it is difficult to target the subsidies to those most in

need: low-income, uninsured persons.

A given employer might have insured and uninsured and high-income and low-income workers. Of the 16 million small firm workers who lack offers of health insurance, only 3 million, or 18 percent, are both uninsured and have family incomes less than 200 percent of the poverty level. Employer-targeted premium subsidies inevitably would convey benefits to many who are neither poor nor uninsured.

Although there have been several proposals to subsidize employer health insurance premiums, issues associated with costs and the inability to target the uninsured may explain why they have not moved forward on Capitol Hill. Much more attention has been focused, instead, on premium subsidies in the form of refundable tax credits targeted at low-income individuals and on expanding public insurance programs.

An alternative adopted by some states is to subsidize insurance premiums only for uninsured, low-income workers in a firm. This approach is not without problems, however. Evidence suggests that low-income workers, like small employers, would not be very responsive to premium subsidies.7 As a result, premium subsidies for individuals would also have to be large-and costly-to have a significant impact on the number of uninsured. Finally, subsidizing individual employees gives firms little incentive to begin offering health insurance. But, attaching subsidies directly to individuals is likely to solve many targeting issues associated with employer premium subsidies. Whether accomplished by subsidizing insurance premiums to individuals or businesses, substantially reducing the number of uninsured through support of the employer-sponsored insurance system will be neither cheap nor easy.

ISSUE BRIEFS are published by the Center for Studying Health System Change.

President: Paul B. Ginsburg

Editor: The Stein Group

For additional copies or to be added

to the mailing list, contact HSC at:

600 Maryland Avenue, SW

Suite 550

Washington, DC 20024-2512

Tel: (202) 554-7549

(for publication information)

Tel: (202) 484-5261

(for general HSC information)

Fax: (202) 484-9258

www.hschange.org