Issue Brief No. 50

February 2002

Ha T. Tu, Marie C. Reed

![]() s policy makers explore options such as tax credits and expansion

of public programs to cover uninsured Americans, working-age adults with chronic

conditions merit special attention. Because their medical needs are likely to

be greater than healthy people’s, coverage expansion proposals that don’t factor

in the greater need of people with chronic conditions are likely to fall short

of reaching this vulnerable group. Often perceived primarily as a problem of the

elderly, chronic conditions are widespread among working-age adults, according

to a new study by the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC). This Issue

Brief examines existing coverage sources for insured working-age people with chronic

conditions and assesses how various coverage proposals might affect uninsured

people with chronic conditions.

s policy makers explore options such as tax credits and expansion

of public programs to cover uninsured Americans, working-age adults with chronic

conditions merit special attention. Because their medical needs are likely to

be greater than healthy people’s, coverage expansion proposals that don’t factor

in the greater need of people with chronic conditions are likely to fall short

of reaching this vulnerable group. Often perceived primarily as a problem of the

elderly, chronic conditions are widespread among working-age adults, according

to a new study by the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC). This Issue

Brief examines existing coverage sources for insured working-age people with chronic

conditions and assesses how various coverage proposals might affect uninsured

people with chronic conditions.

![]() n estimated 60 million working-age Americans (18 to 64) have

at least one chronic health condition such as diabetes, asthma or depression.

About 7.4 million working-age Americans with chronic conditions were uninsured

in 1999, according to HSC’s Community Tracking Study (CTS) Household Survey (see

Methodology). Uninsured people with chronic conditions report worse health

and are three times more likely not to get needed medical care than privately

insured people with chronic conditions.1

n estimated 60 million working-age Americans (18 to 64) have

at least one chronic health condition such as diabetes, asthma or depression.

About 7.4 million working-age Americans with chronic conditions were uninsured

in 1999, according to HSC’s Community Tracking Study (CTS) Household Survey (see

Methodology). Uninsured people with chronic conditions report worse health

and are three times more likely not to get needed medical care than privately

insured people with chronic conditions.1

The vast majority of uninsured people with chronic conditions delayed or did not get needed care because of cost. About 63 percent of the working-age uninsured with chronic conditions-roughly 4.7 million Americans-have family incomes below 200 percent of poverty, or about $35,000 a year for a family of four in 2001. Unlike the elderly, working-age adults with chronic conditions do not qualify for Medicare unless they have severe disabilities, making access to health insurance a concern for this population.

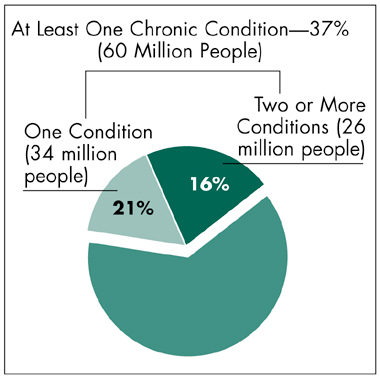

Sixteen percent of all working-age adults, or 43 percent of all Americans with chronic conditions, report having more than one chronic condition (see Figure 1). People with multiple chronic conditions are particularly vulnerable because they have more functional limitations and disabilities, face higher health care costs and encounter more challenges getting medical care.

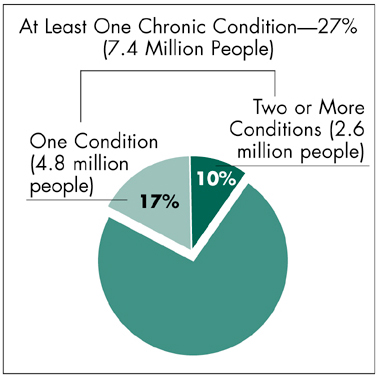

People with chronic conditions represent a substantial portion of the total uninsured population (see Figure 2). Estimating conservatively, more than one-quarter of uninsured working-age adults have chronic conditions, and 10 percent have multiple conditions. A large majority-82 percent- lacks access to employer-sponsored insurance because there is no worker in the family or the worker is ineligible for coverage.

The findings for this Issue Brief are based on an analysis of the 1998-99 CTS Household Survey. The survey asked respondents aged 18 to 64 whether they had been diagnosed with one of more than 20 chronic conditions and had seen a doctor in the past two years for the condition. The list of chronic conditions includes asthma, diabetes, arthritis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart disease, stroke, hypertension, high cholesterol, cancer (skin, lung, prostate, breast, colon), benign prostate enlargement, abnormal uterine bleeding, severe headaches, cataracts, HIV/AIDS and depression. Because the CTS list of conditions is not exhaustive, the estimate of the prevalence of chronic illness is likely somewhat conservative.

Figure 1

Chronic Conditions Among Adults 18-64 Years Old

Source: Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1998-99

![]() n 1999, 71 percent of working-age adults with chronic conditions

were privately insured; Medicare and/or Medicaid covered 14 percent; 12 percent

were uninsured; and the remainder had other coverage. Private, employer-sponsored

insurance is the major source of insurance coverage for nonelderly adults regardless

of health status (see Table 1). Working-age adults with

chronic conditions are more likely than healthy2 working-age

adults to be covered by public insurance-14 percent vs. 3 percent.

n 1999, 71 percent of working-age adults with chronic conditions

were privately insured; Medicare and/or Medicaid covered 14 percent; 12 percent

were uninsured; and the remainder had other coverage. Private, employer-sponsored

insurance is the major source of insurance coverage for nonelderly adults regardless

of health status (see Table 1). Working-age adults with

chronic conditions are more likely than healthy2 working-age

adults to be covered by public insurance-14 percent vs. 3 percent.

Substitution of public insurance for private becomes more pronounced as the number of chronic conditions increases. Medicare beneficiaries, for example, account for only 4 percent of the working-age population with one chronic condition, or about 1.2 million people, but they comprise 12 percent of the group with multiple conditions, or 3.1 million people. This pattern is not surprising because Medicare eligibility for people under age 65 requires severe disability for a prolonged period,3 and people with multiple chronic conditions are much more likely to have severe disabilities.

Uninsurance rates are lower for the working-age population with chronic conditions compared to the healthy population because the increase in public insurance coverage exceeds the drop-off in private coverage. The reduction in uninsurance is modest for those with one chronic condition compared to those who are healthy-14 percent vs. 15 percent-while the uninsurance rate for people with multiple chronic conditions is significantly lower at 10 percent.

| Table 1 Types of Insurance Coverage for Adults 18-64 Years Old |

||||

| Healthy |

Chronically Ill |

|||

| |

All* |

One Condition* |

Two or More Conditions* |

|

| Private Insurance: Employer-Sponsored | 73% |

66% |

70% |

61% |

| Private Insurance: Individual | 7 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

| Medicare | 0 |

5 |

3 |

9 |

| Medicare and Medicaid (Dual Eligible) | 0 |

2 |

1 |

3 |

| Medicaid/Other State | 3 |

7 |

5 |

9 |

| Other Insurance | 1 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

| Uninsured | 15 |

12 |

14 |

10 |

| Total** | 99 |

99 |

100 |

100 |

| * All differences from healthy-population estimates

are statistically significant at p<.05 level. ** May not sum to 100 due to rounding. Source: Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1998-99 |

||||

![]() ower rates of private insurance coverage for people with chronic

conditions than for healthy people can be attributed in part to lower employment

rates, and, consequently, less access to employer-sponsored coverage (see

Table 2). The decline in the employment rate becomes more pronounced for people

with multiple chronic conditions-only 56 percent employed vs. 72 percent of those

with one condition and 83 percent of healthy people.

ower rates of private insurance coverage for people with chronic

conditions than for healthy people can be attributed in part to lower employment

rates, and, consequently, less access to employer-sponsored coverage (see

Table 2). The decline in the employment rate becomes more pronounced for people

with multiple chronic conditions-only 56 percent employed vs. 72 percent of those

with one condition and 83 percent of healthy people.

The gap in access to employer-sponsored coverage between healthy people and people with chronic conditions is not as large as the difference in employment rates between the two groups. A substantial number of people without access to insurance through their own employment do have access through a family member’s employment. Among employed individuals, the likelihood of having access to health insurance through their own jobs actually increases as chronic conditions increase.4 This pattern suggests that health insurance coverage is a more important priority for workers with chronic conditions and plays a larger role in their decisions about where to work than for healthy adults.

Among the employed, people with chronic conditions are less likely to work for small firms and more likely to work for government. The tendency of workers with chronic conditions to substitute government work for small firm employment is consistent with the idea that workers sort themselves into different types of employers based on how important health insurance is to them.

Unlike small firms, government and large firms almost universally offer coverage. Additionally, government tends to offer better benefits and a broader range of insurance choices: 69 percent of government employees are offered a choice of health plans, compared to only 50 percent of workers in large firms and 16 percent in small firms. More choice among insurance offerings and more generous benefits may explain why people with chronic conditions are more likely to work for government. Other factors, such as greater job stability and, perhaps, more job opportunities for people with disabilities, also may explain why government appears to be somewhat of a safe haven for workers with chronic conditions.

These employment patterns suggest that some workers with chronic conditions may find themselves locked into certain jobs because of health insurance and other benefits. The findings also suggest that the sharing of risk and the higher insurance costs for people with chronic conditions are distributed unevenly, with public employers and employees possibly bearing a disproportionate share.

| Table 2 Employment and Access to Employer-Sponsored Insurance (ESI) Coverage, Adults 18-64 Years Old |

||||

| Healthy |

Chronically Ill |

|||

| |

All* |

Condition* |

Two or More Conditions* |

|

| Percent Employed | 83% |

65% |

72% |

56% |

| Access to Coverage | ||||

| Percent with Access to ESI Through Own Employer | 63 |

54 |

58 |

49 |

| Percent with Access to ESI at the Family Level | 78 |

72 |

76 |

68 |

| Type of Employer (Among Those Employed) | ||||

| Firms with Fewer Than 50 Employees | 32 |

27 |

28 |

25 |

| Firms with 50 or More Employees | 53 |

53 |

53 |

53 |

| Government | 15 |

20 |

19 |

22 |

| * All differences from healthy-population

estimates are statistically significant at p<.05 level, except for estimates

of percentage employed in firms with 50 or more employees. Source: Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1998-99 |

||||

![]() s health insurance premiums continue to

rise, policy makers need to be concerned

not only with expanding coverage to the

uninsured but also with the potential loss

of coverage among those now insured.

s health insurance premiums continue to

rise, policy makers need to be concerned

not only with expanding coverage to the

uninsured but also with the potential loss

of coverage among those now insured.

Policy makers are debating different proposals to expand health insurance coverage, but none focuses specifically on uninsured people with chronic conditions. Yet, because of their medical needs, people with chronic conditions are precisely the ones who can benefit most from insurance, especially if they also have low incomes.

Expanding coverage to people with chronic conditions poses difficult challenges for policy makers. Chronic conditions, by definition, entail the need for more costly and intensive health care services. This element of known higher expenses, in excess of the standard insurance risk, causes conventional concepts of insurance and risk to break down when applied to people with chronic conditions.

Targeting insurance expansions toward those with chronic conditions would be costly because subsidies for the chronically ill would have to be larger than the average standard-risk subsidy. In addition, policy makers would face considerable challenges determining which conditions-and what level of severity-should trigger eligibility.

Another challenge would be determining appropriate subsidy amounts that take into account both financial need and severity of the chronic condition. And, policy makers would face a trade-off between paying for a potentially costly eligibility determination and verification system or using available resources to cover a broader population.

![]() erhaps most problematic for those with

chronic conditions are proposals to give

people tax credits to buy insurance in the

individual insurance market. Recent

research provides compelling evidence that

consumers in less-than-perfect health face

substantial obstacles when they try to buy

individual insurance.5

People with conditions

as mild as hay fever rarely receive

"clean offers" of insurance, or acceptance

for standard coverage at standard rates.

More often, they receive offers with premium

surcharges, offers excluding certain

conditions or outright coverage denials.

Private markets cannot be expected to

absorb the excess risk and health care costs

of people with chronic conditions. And,

because the individual insurance market

can associate such risks with particular

individuals, the individual market could

address the needs of people with chronic

conditions in a meaningful way only if tax

credit amounts were adjusted to reflect

their higher expected costs.

erhaps most problematic for those with

chronic conditions are proposals to give

people tax credits to buy insurance in the

individual insurance market. Recent

research provides compelling evidence that

consumers in less-than-perfect health face

substantial obstacles when they try to buy

individual insurance.5

People with conditions

as mild as hay fever rarely receive

"clean offers" of insurance, or acceptance

for standard coverage at standard rates.

More often, they receive offers with premium

surcharges, offers excluding certain

conditions or outright coverage denials.

Private markets cannot be expected to

absorb the excess risk and health care costs

of people with chronic conditions. And,

because the individual insurance market

can associate such risks with particular

individuals, the individual market could

address the needs of people with chronic

conditions in a meaningful way only if tax

credit amounts were adjusted to reflect

their higher expected costs.

To avoid the problems of the individual market, some tax-credit proposals seek to expand insurance in the workplace, but these proposals have limitations, too. Subsidies aimed at helping employees pay their share of premiums would reach few of the uninsured with chronic conditions, since less than one in five has access to employer-sponsored insurance. Subsidies targeted at small employers to encourage them to offer health insurance have a larger potential reach: 40 percent of the uninsured with chronic conditions either work for or have a family member working for small employers not offering insurance.

However, new HSC research suggests that employer-targeted subsidies are unlikely to induce many small firms to offer insurance.6 And, even in cases where small employers do find the subsidies attractive enough to begin offering insurance, paying the employee share of premiums would pose a challenge for low-income workers, especially during a time of rapidly rising premiums.

Expansions of public insurance programs provide another approach for covering the uninsured with chronic conditions. Some policy makers favor expanding the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) to cover parents of eligible children. Roughly a third of uninsured adults with chronic conditions might qualify for a SCHIP expansion to parents.

To enhance coverage significantly, a much larger-scale public expansion would be required. For instance, eliminating all Medicaid eligibility requirements except low income would benefit a majority of the uninsured, including almost two-thirds of those with chronic conditions. While this approach does not target people with chronic conditions, it would capture a significant majority. Such sweeping expansions, however, carry high price tags and have the potential to crowd out private insurance. As the debate continues about how to expand coverage, policy makers should examine the impact of coverage proposals through a lens focused on low-income, uninsured people with chronic conditions.

| 1. | Reed, Marie C., and Ha T. Tu, Triple Jeopardy: Low Income, Chronically Ill and Uninsured in America, Issue Brief No. 49, Center for Studying Health System Change (February 2002). |

| 2. | Healthy persons are defined as those who report good to excellent health, none of the chronic conditions listed on the Household Survey (see Methodology) and none of the physical limitations on SF-12 questions. |

| 3. | Persons under age 65 who have received Social Security or Railroad Retirement disability payments for a 24-month period are automatically eligible for Medicare. Disability is also one of the Medicaid eligibility categories for adults under age 65. |

| 4. | This can be seen by dividing the second row of Table 2 by the first row. For example, 58/72 (81 percent) of the employed who have one chronic condition are offered insurance through their own jobs, compared to 49/56 (88 percent) of the employed who have multiple conditions. |

| 5. | Pollitz, Karen, et al., How Accessible Is Individual Health Insurance for Consumers in Less-than-Perfect Health? The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation (June 2001). |

| 6. | Reschovsky, James D., and Jack Hadley, Employer Health Insurance Premium Subsidies Unlikely to Enhance Coverage Significantly, Issue Brief No. 46, Center for Studying Health System Change (December 2001); Hadley, Jack, and James D. Reschovsky, "Small Firms’ Demand for Health Insurance: The Decision to Offer," Inquiry (forthcoming). |

President: Paul B. Ginsburg

Director of Public Affairs: Richard Sorian

Editor: The Stein Group

For additional copies or to be added

to the mailing list, contact HSC at:

600 Maryland Avenue, SW

Suite 550

Washington, DC 20024-2512

Tel: (202) 554-7549

(for publication information)

Tel: (202) 484-5261

(for general HSC information)

Fax: (202) 484-9258

www.hschange.org