Issue Brief No. 56

October 2002

Ashley C. Short, Cara S. Lesser

![]() ising premiums and a weak economy are generating questions about the potential

erosion of health insurance coverage, particularly for the more than 46 million

Americans who work for small firms.1 People working in small firms typically have

less access to coverage than those in large firms. In 2000 and early 2001, the Center

for Studying Health System Change (HSC) conducted its third round of site visits to

12 nationally representative metropolitan areas2

and found that while few small employers actually dropped coverage, many increased the employee share of premiums,

raised copayments and deductibles, switched products and carriers and/or

reduced benefits. With the U.S. economy now in rougher shape, small employers

may pare back coverage even more, putting affordable health care further out of the

reach of workers and their families.

ising premiums and a weak economy are generating questions about the potential

erosion of health insurance coverage, particularly for the more than 46 million

Americans who work for small firms.1 People working in small firms typically have

less access to coverage than those in large firms. In 2000 and early 2001, the Center

for Studying Health System Change (HSC) conducted its third round of site visits to

12 nationally representative metropolitan areas2

and found that while few small employers actually dropped coverage, many increased the employee share of premiums,

raised copayments and deductibles, switched products and carriers and/or

reduced benefits. With the U.S. economy now in rougher shape, small employers

may pare back coverage even more, putting affordable health care further out of the

reach of workers and their families.

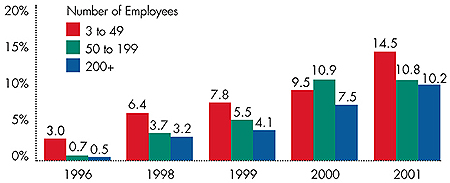

![]() he rising cost of health insurance

has led small employers to

make important changes in the health

insurance they offer their workers.

Insurance premiums rose rapidly for

all firms in 2000 and 2001, but small

firms were hit particularly hard, with

an average hike of 14.5 percent in

2001 (see Figure 1).

he rising cost of health insurance

has led small employers to

make important changes in the health

insurance they offer their workers.

Insurance premiums rose rapidly for

all firms in 2000 and 2001, but small

firms were hit particularly hard, with

an average hike of 14.5 percent in

2001 (see Figure 1).

Large employers generally made only modest changes to their insurance offerings in response to rising premiums, such as altering cost sharing.3 But small firms often have more difficulty than larger employers in affording health insurance for their workers (see box). Indeed, small employers in most of the 12 sites studied took more dramatic action, including:

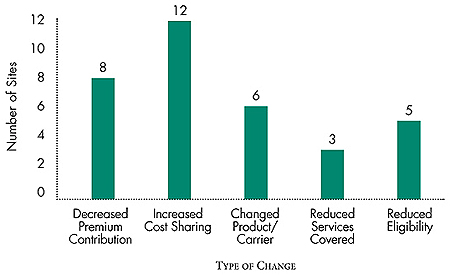

Although the extent to which employers adopted these strategies varied (see Figure 2), the overall trend suggests that people working for small firms were beginning to face a greater financial burden for their health care costs—even at a time when the economy was relatively strong.

Figure 1

Percent Increase in Premiums by Firm Size

Source: The Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Research and Educational

Trust’s Employer Health Benefits Annual Survey

Figure 2

Number of Sites Reporting Changes in Small Employers’ Benefits Offerings

Source: Community Tracking Study site visits, 2000-01

![]() mall employers in more than half the

sites studied began shifting a greater

share of premiums to employees in

2000 and 2001. Many firms set their

premium contributions at a fixed percentage,

thus transferring some of the

burden of premium increases to

employees. Some small employers

decreased the percentage they contributed. In a few sites, some employers

went a step further and abandoned the fixed

percentage approach in favor of making a

fixed-dollar contribution, leaving employees

responsible for any premium costs above that

amount. This strategy shifted the premium

increases directly to employees.

mall employers in more than half the

sites studied began shifting a greater

share of premiums to employees in

2000 and 2001. Many firms set their

premium contributions at a fixed percentage,

thus transferring some of the

burden of premium increases to

employees. Some small employers

decreased the percentage they contributed. In a few sites, some employers

went a step further and abandoned the fixed

percentage approach in favor of making a

fixed-dollar contribution, leaving employees

responsible for any premium costs above that

amount. This strategy shifted the premium

increases directly to employees.

Another particularly troubling way small employers reduced their exposure to premium increases was to drop all contributions for dependent coverage. Such policies discouraged employees from covering their dependents and created the potential for adverse selection, since higher costs might deter healthier families from enrolling. In Miami, for instance, a broker reported that this trend was most pronounced in one- to 10-person firms, and that few employees of these firms elected dependent coverage as a result.

![]() mall firms in all 12 sites sought to minimize

premium increases by adding or increasing

deductibles, copayments and coinsurance.

These measures were intended to reduce the

current year’s premiums by placing a higher

cost burden on consumers who used services.

In addition, they potentially could rein in

utilization, thereby offsetting future increases.

mall firms in all 12 sites sought to minimize

premium increases by adding or increasing

deductibles, copayments and coinsurance.

These measures were intended to reduce the

current year’s premiums by placing a higher

cost burden on consumers who used services.

In addition, they potentially could rein in

utilization, thereby offsetting future increases.

For example, a Syracuse insurance broker reported that plans had added deductibles of $200 to $500 for hospital stays. In Boston, plans increased copayments for office visits from $5 to $10. And in Little Rock, Ark., some small employers raised coinsurance to as much as 40 percent or 50 percent.

Movement toward a three-tier prescription drug benefit was the most commonly reported change in out-of-pocket expenses. Under this scheme, consumers pay progressively more for generic drugs, preferred brand-name drugs and nonpreferred brand-name drugs. Some employers also replaced fixed dollar copayments with a percentage coinsurance, increasing workers’ costs even more.

![]() mall firms have more flexibility than large

firms to switch products and plans. As

premiums rose in 2000 and 2001, some

small employers moved to less expensive and

more restrictive product types to reduce net

increases in premiums. For example, some

employers in Orange County, Calif., moved

from preferred provider organizations (PPOs)

to point-of-service products, while in Cleveland

some switched from PPOs to health maintenance

organizations (HMOs).

mall firms have more flexibility than large

firms to switch products and plans. As

premiums rose in 2000 and 2001, some

small employers moved to less expensive and

more restrictive product types to reduce net

increases in premiums. For example, some

employers in Orange County, Calif., moved

from preferred provider organizations (PPOs)

to point-of-service products, while in Cleveland

some switched from PPOs to health maintenance

organizations (HMOs).

Other small employers found they could save on premiums simply by switching carriers. Some small employers routinely switched plans for even small cost savings, but with rapidly rising premiums, more found themselves shopping around for better deals.

While changes such as moving to more restrictive forms of coverage and switching health plans do maintain coverage, they exact a toll on consumers. Switching products or plans, particularly a move to managed care options, can disrupt relationships between patients and their physicians. For example, patients whose employers switch to HMOs may find their physicians do not participate in the plan, forcing them either to change doctors or to pay the full cost of their care.

![]() either small nor large employers relied

heavily on reductions in services covered to

counteract premium increases. In some communities,

however, small employers began to

chip away at their benefits offerings. Some

plans in Miami, for example, eliminated coverage

for fertility treatment, and small firms

in Indianapolis were considering whether to

reduce their coverage for mental illness.

either small nor large employers relied

heavily on reductions in services covered to

counteract premium increases. In some communities,

however, small employers began to

chip away at their benefits offerings. Some

plans in Miami, for example, eliminated coverage

for fertility treatment, and small firms

in Indianapolis were considering whether to

reduce their coverage for mental illness.

At the same time, large and small employers were reexamining their eligibility criteria. Large companies discussed dropping retiree coverage, as did some of the relatively few small firms offering such benefits. Small employers in several sites focused on other areas to scale back eligibility, establishing stricter rules for employees and dependents. For example, some small employers in Syracuse extended the waiting period for employee eligibility, and respondents in Phoenix and Boston predicted employers in those cities would adopt similar policies. Small employers in Miami and Greenville, S.C., went one step beyond eliminating the premium contribution for dependents and dropped dependent coverage entirely, creating concerns among policy makers about the increasing number of uninsured people in the area.

Despite speculation that employers would drop coverage altogether, there was little evidence of this during the 2000-01 site visits. One exception was Little Rock, where some small employers allowed employees to use pretax dollars to buy individual insurance. While employers sometimes use this approach to share the cost of individual coverage, the Little Rock firms required workers to bear the full cost of coverage in the more expensive individual market.

![]() ven in the thriving economy of 2000 and

early 2001, small employers’ responses to rising

premiums were making coverage and

care more expensive for workers and their

families. Increases in employees’ share of the

premium and tighter eligibility requirements

intensified the financial burden of purchasing

coverage. Meanwhile, increased cost sharing

and reductions in benefits strained the

pocketbooks of even those employees who

could afford coverage. Indeed, recent Census

Bureau data show a decline in the proportion

of individuals working in firms with fewer

than 25 employee who received coverage

through their employer in 2001.7

Rising premiums

also may have discouraged some

firms from beginning to offer coverage.

ven in the thriving economy of 2000 and

early 2001, small employers’ responses to rising

premiums were making coverage and

care more expensive for workers and their

families. Increases in employees’ share of the

premium and tighter eligibility requirements

intensified the financial burden of purchasing

coverage. Meanwhile, increased cost sharing

and reductions in benefits strained the

pocketbooks of even those employees who

could afford coverage. Indeed, recent Census

Bureau data show a decline in the proportion

of individuals working in firms with fewer

than 25 employee who received coverage

through their employer in 2001.7

Rising premiums

also may have discouraged some

firms from beginning to offer coverage.

A new, more burdensome round of premium increases has occurred since these site visits, as the U.S. economy has remained sluggish. With financial pressures building, small employers are likely to cut back even more on health insurance offerings. Some may continue to make the kind of changes observed in 2000 and 2001. Others may find they have exhausted their arsenal of cost-cutting mechanisms and decide to drop coverage altogether, exacerbating the national problem of the uninsured and feeding future cost increases.

![]() ealth insurance coverage generally

costs more for firms with fewer than

50 employees, and many have limited

resources to devote to health benefits.

For example, less than two-thirds (62%)

of small firms offered insurance in 2001,

compared with 97 percent of larger firms.4

Even when small firms offer insurance,

fewer employees enroll, possibly because

they typically earn lower wages than

employees of large firms.5

Indeed, one

study found that only 74 percent of

employees in firms with fewer than 10

employees enroll in their firms’ health

insurance offerings, compared with 84

percent of employees in firms with more

than 100 workers.6

ealth insurance coverage generally

costs more for firms with fewer than

50 employees, and many have limited

resources to devote to health benefits.

For example, less than two-thirds (62%)

of small firms offered insurance in 2001,

compared with 97 percent of larger firms.4

Even when small firms offer insurance,

fewer employees enroll, possibly because

they typically earn lower wages than

employees of large firms.5

Indeed, one

study found that only 74 percent of

employees in firms with fewer than 10

employees enroll in their firms’ health

insurance offerings, compared with 84

percent of employees in firms with more

than 100 workers.6

| 1. | U.S. Census Bureau, County Business Patterns, 2000. The U.S. Census Bureau defines small firms as those with between one and 49 employees. |

| 2. | For site visit methodology, see www.hschange.org. |

| 3. | Trude, Sally, et al., “Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance: Pressing Problems, Incremental Changes,” Health Affairs, Vol. 21, No. 1 (January/February 2002). |

| 4. | The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Research and Educational Trust, Employer Health Benefits: 2001 Annual Survey, The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation (2001). The Kaiser Family Foundation defines small firms as those with between three and 49 employees. |

| 5. | Oi, Walter Y., and Todd L. Idson, “Firm Size and Wages,” in O. Ashenfelter and D. Card, eds., The Handbook of Labor Economics, Volume III, Amsterdam: North-Holland (1999). |

| 6. | Cooper, Philip F., and Barbara Steinberg Schone, “More Offers, Fewer Takers for Employment-Based Health Insurance: 1987 and 1996,” Health Affairs, Vol. 16, No. 6 (November/December 1997). |

| 7. | U.S. Census Bureau, Health Insurance Coverage: 2001. |

ISSUE BRIEFS are published by the Center for Studying Health System Change.

President: Paul B. Ginsburg

Director of Public Affairs: Richard Sorian

Director of Site Visits: Cara S. Lesser

Editor: The Stein Group

For additional copies or to be added

to the mailing list, contact HSC at:

600 Maryland Avenue, SW

Suite 550

Washington, DC 20024-2512

Tel: (202) 554-7549

(for publication information)

Tel: (202) 484-5261

(for general HSC information)

Fax: (202) 484-9258

www.hschange.org