Issue Brief No. 59

December 2002

Peter J. Cunningham, James D. Reschovsky, Jack Hadley

![]() ecent expansions of the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP)

and Medicaid have led to significant shifts in insurance coverage for children. New

findings from the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC) show that the

proportion of low-income children who were uninsured dropped from 20.1 percent

in 1997 to 16.1 percent in 2001, a result of significant increases in public program

coverage. The net effect of these gains in coverage was limited, however, by a decline in

private insurance coverage (from 47% in 1997 to 42.3% in 2001). The drop in private

insurance was due, in part, to substitution of public for private insurance coverage.

ecent expansions of the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP)

and Medicaid have led to significant shifts in insurance coverage for children. New

findings from the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC) show that the

proportion of low-income children who were uninsured dropped from 20.1 percent

in 1997 to 16.1 percent in 2001, a result of significant increases in public program

coverage. The net effect of these gains in coverage was limited, however, by a decline in

private insurance coverage (from 47% in 1997 to 42.3% in 2001). The drop in private

insurance was due, in part, to substitution of public for private insurance coverage.

![]() CHIP was enacted in 1997 to reduce the number of low-income

children without health insurance, especially those in families who lacked access to employer-sponsored coverage and/or Medicaid. Under SCHIP, states could expand eligibility in existing Medicaid programs or establish separate child health programs. To limit the number of privately insured children who might switch to SCHIP and Medicaid, Congress required states to adopt strategies to prevent children

with private insurance coverage from enrolling. Many states require applicants to be uninsured for a period of time (usually three to six months) before being allowed to enroll; others collect information on current and past insurance coverage during the application process; and still other states impose higher cost sharing than is customary in public insurance programs for low-income people.

CHIP was enacted in 1997 to reduce the number of low-income

children without health insurance, especially those in families who lacked access to employer-sponsored coverage and/or Medicaid. Under SCHIP, states could expand eligibility in existing Medicaid programs or establish separate child health programs. To limit the number of privately insured children who might switch to SCHIP and Medicaid, Congress required states to adopt strategies to prevent children

with private insurance coverage from enrolling. Many states require applicants to be uninsured for a period of time (usually three to six months) before being allowed to enroll; others collect information on current and past insurance coverage during the application process; and still other states impose higher cost sharing than is customary in public insurance programs for low-income people.

States also adopted a variety of strategies to increase enrollment among eligible children, including reducing administrative barriers, simplifying the application process and developing or expanding outreach activities to promote the program and encourage parents to enroll their eligible children.

Enrollment in all SCHIP-related programs reached 3.5 million children by late 2001. 1 In addition, Medicaid enrollment among those eligible under pre-SCHIP rules grew, due in part to increased outreach and simplification of enrollment. 2

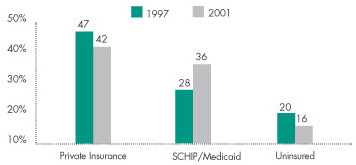

![]() esults from the Community Tracking Study (CTS) Household Survey covering

1997-2001 show that among children in families with incomes below 200 percent

of the federal poverty level (or about $36,000 for a family of four in 2001),

the proportion with SCHIP or Medicaid coverage increased nearly eight percentage

points, from 28.4 percent in 1997 (before SCHIP was enacted) to 36 percent in

2001 (see Figure 1 and Table 1).

This increase in public coverage came from both the uninsured and those with

private insurance coverage. The proportion of low-income children who were uninsured

dropped four percentage points, from 20.1 percent in 1997 to 16.1 percent in

2001, while the proportion of privately insured children dropped 4.7 percentage

points, from 47 percent in 1997 to 42.3 percent in 2001. The largest changes

in coverage occurred among children in families with incomes between 100 percent

and 200 percent of poverty, the primary SCHIP target group.

esults from the Community Tracking Study (CTS) Household Survey covering

1997-2001 show that among children in families with incomes below 200 percent

of the federal poverty level (or about $36,000 for a family of four in 2001),

the proportion with SCHIP or Medicaid coverage increased nearly eight percentage

points, from 28.4 percent in 1997 (before SCHIP was enacted) to 36 percent in

2001 (see Figure 1 and Table 1).

This increase in public coverage came from both the uninsured and those with

private insurance coverage. The proportion of low-income children who were uninsured

dropped four percentage points, from 20.1 percent in 1997 to 16.1 percent in

2001, while the proportion of privately insured children dropped 4.7 percentage

points, from 47 percent in 1997 to 42.3 percent in 2001. The largest changes

in coverage occurred among children in families with incomes between 100 percent

and 200 percent of poverty, the primary SCHIP target group.

| Table 1: Health Insurance Coverage, Children Age 19 and Under | ||||

|

PERCENT WITH COVERAGE

|

Change

1997-2001 |

|||

|

1997

|

1999

|

2001

|

||

| ALL CHILDREN AGE 19 AND UNDER | ||||

| PRIVATE INSURANCE |

70.8%

|

69.3%

|

69.9%

|

-0.9%

|

| SCHIP/MEDICAID |

14.2

|

15.4

|

16.8

|

2.6 #

|

| OTHER 1 |

3.6

|

3.8

|

3.9

|

0.3

|

| UNINSURED |

11.5

|

11.5

|

9.4*

|

-2.1 #

|

| 200% OF POVERTY OR HIGHER | ||||

| PRIVATE INSURANCE |

89.3

|

89.8

|

86.0*

|

-3.3#

|

| SCHIP/MEDICAID |

3.1

|

2.7

|

5.6*

|

2.5#

|

| OTHER 1 |

2.9

|

2.6

|

2.8

|

-0.1

|

| UNINSURED |

4.7

|

4.9

|

5.5

|

0.8

|

| LESS THAN 200% OF POVERTY | ||||

| PRIVATE INSURANCE |

47.0

|

41.5*

|

42.3

|

-4.7 #

|

| SCHIP/MEDICAID |

28.4

|

32.6*

|

36.0

|

7.6 #

|

| OTHER 1 |

4.6

|

5.5

|

5.7

|

1.1

|

| UNINSURED |

20.1

|

20.5

|

16.1*

|

-4.0 #

|

| BETWEEN 100-200% | ||||

| PRIVATE INSURANCE |

63.8

|

56.2*

|

57.1

|

-6.7 #

|

| SCHIP/MEDICAID |

13.4

|

20.8*

|

24.2

|

10.8 #

|

| OTHER 1 |

4.0

|

5.1

|

5.8

|

1.8 #

|

| UNINSURED |

18.9

|

17.9

|

13.0*

|

-5.9 #

|

| LESS THAN 100% OF POVERTY | ||||

| PRIVATE INSURANCE |

25.5

|

23.0

|

23.6

|

-1.9

|

| SCHIP/MEDICAID |

47.6

|

47.3

|

50.9

|

3.3

|

| OTHER 1 |

5.4

|

5.9

|

5.5

|

0.1

|

| UNINSURED |

21.5

|

23.7

|

20.0

|

-1.5

|

| 1 "Other" includes those covered

by military insurance, Indian Health Services, medicare and other public

programs. * Change from previous survey is statistically significant at p<.05 level, # Change from 1997 to 2001 is statistically significant at p<.05 level. Source HSC Community Tracking Study Household Survey |

||||

![]() overage expansions due to SCHIP vary from state to state. For example, some states were already covering large numbers of low-income children in Medicaid and other state-run programs, so they did not need to expand eligibility as much as other states did. Thirteen states and the District of Columbia (representing about 40% of low-income children) had large expansions in eligibility (defined as a 50 percentage point or higher increase in the proportion of eligible low-income children), while six states (representing about 16% of low-income children) had no eligibility expansions. 3

overage expansions due to SCHIP vary from state to state. For example, some states were already covering large numbers of low-income children in Medicaid and other state-run programs, so they did not need to expand eligibility as much as other states did. Thirteen states and the District of Columbia (representing about 40% of low-income children) had large expansions in eligibility (defined as a 50 percentage point or higher increase in the proportion of eligible low-income children), while six states (representing about 16% of low-income children) had no eligibility expansions. 3

States that expanded eligibility by 50 percentage points or more saw the largest changes in public and private coverage rates. In these states, the fraction of low-income children with SCHIP or Medicaid coverage jumped almost 14 percentage points, from 24.5 percent in 1997 to 38.3 percent in 2001 (see Table 2). By comparison, coverage in states that had smaller or no eligibility expansions increased only about three percentage points, a change that was not statistically significant. Virtually all of the decrease in private insurance coverage among low-income children between 1997 and 2001 occurred in those states with the largest expansions in eligibility. 4

In contrast, the percent of low-income children who were uninsured decreased significantly in states that had small eligibility expansions as well as those with larger expansions. Although the size of the decrease in the percent uninsured was slightly higher in states with the largest expansions in eligibility (5.3 percentage points, compared with 3.4 percentage points for states with smaller or no changes in eligibility), the differential is much smaller than for the change in public and private coverage.

| TABLE 2: Changes in SCHIP/Medicaid Coverage Among Low-Income Children Age 19 and Under | |||

1997 |

2001 |

CHANGE 1997-2001 |

|

| PERCENT WITH SCHIP/MEDICAID | 28.4% |

36.0% |

7.6%* |

| IN STATES WITH LARGE INCREASE IN ELIGIBILITY 2 |

24.5 |

38.3 |

13.8* |

| IN STATES WITH SMALLER OR NO INCREASE IN ELIGIBILITY |

30.9 |

34.1 |

3.2 |

| PERCENT WITH PRIVATE INSURANCE | 47.0 |

42.3 |

-4.7* |

| IN STATES WITH LARGE INCREASE IN ELIGIBILITY 2 |

46.1 |

37.0 |

-9.1* |

| IN STATES WITH SMALLER OR NO INCREASE IN ELIGIBILITY |

47.5 |

46.4 |

-1.1 |

| PERCENT WITH OTHER COVERAGE | 4.6 |

5.7 |

1.1 |

| IN STATES WITH LARGE INCREASE IN ELIGIBILITY 2 |

5.3 |

5.9 |

0.6 |

| IN STATES WITH SMALLER OR NO INCREASE IN ELIGIBILITY |

4.2 |

5.5 |

1.3 |

| PERCENT UNINSURED | 20.1 |

16.1 |

-4.0* |

| IN STATES WITH LARGE INCREASE IN ELIGIBILITY 2 |

24.1 |

18.8 |

-5.3* |

| IN STATES WITH SMALLER OR NO INCREASE IN ELIGIBILITY |

17.4 |

14.0 |

-3.4* |

| 1 By extent of change in eligibility.

2 Large increase in eligibility is defined as an increase of 50 percentage points or higher in the percent of low-income children eligible for SCHIP/Medicaid coverage, when state rules are applied to a standardized population of low-income children. * Change is statistically significant at p<.05 level. Source: HSC Community Tracking Study Household Survey |

|||

![]() hat the percentage of uninsured children declined even in areas with little or no

increase in eligibility suggests that other factors—especially outreach efforts to increase participation and reduce administrative barriers—contributed to the decrease as well. Many parents of uninsured children

who are eligible for SCHIP or Medicaid are not aware of the programs, do not believe their children are eligible, are not interested or are discouraged by onerous enrollment procedures. 5

hat the percentage of uninsured children declined even in areas with little or no

increase in eligibility suggests that other factors—especially outreach efforts to increase participation and reduce administrative barriers—contributed to the decrease as well. Many parents of uninsured children

who are eligible for SCHIP or Medicaid are not aware of the programs, do not believe their children are eligible, are not interested or are discouraged by onerous enrollment procedures. 5

States have made extensive efforts to reach out to families whose children may be eligible for SCHIP and to reduce administrative barriers to enrollment. Federal and state governments have committed substantial resources to advertising, Web sites and toll-free hotlines to promote enrollment. States have worked with schools, health care providers, private employers and social service agencies to screen for eligible children and encourage their parents to get them enrolled.

Since enrollment procedures often have been cited as barriers to enrollment in Medicaid, most states have also tried to streamline their procedures for SCHIP and Medicaid, such as shortening the application form, not requiring face-to-face interviews or asset tests and allowing presumptive eligibility (granting short-term eligibility before an actual determination is made so the child can receive immediate health services).

Anecdotal evidence and case study findings suggest that these activities are increasing participation of eligible children. 6 Increased participation also may help to explain the near doubling of SCHIP enrollment between 2000 and 2001, despite the fact that most of the major eligibility expansions occurred before 2000. 7 Findings from the CTS show that participation rates among low-income children eligible for SCHIP or Medicaid increased from 60 percent in 1999 to 66 percent in 2001. The increases were especially large in communities that had the highest rates of uninsured children.8

![]() CHIP expansions also resulted in some substitution of public for private coverage, sometimes also referred to as crowd out. Substitution occurs when some children who enroll in SCHIP and Medicaid would have been enrolled in private insurance coverage had there been no public program expansions. This

may include parents taking advantage of free or lower-cost public coverage by directly switching their children from private to public coverage (which states were required to try and prevent). But substitution also could occur indirectly over time as public coverage expansions create additional avenues of coverage for children whose economic circumstances change.

CHIP expansions also resulted in some substitution of public for private coverage, sometimes also referred to as crowd out. Substitution occurs when some children who enroll in SCHIP and Medicaid would have been enrolled in private insurance coverage had there been no public program expansions. This

may include parents taking advantage of free or lower-cost public coverage by directly switching their children from private to public coverage (which states were required to try and prevent). But substitution also could occur indirectly over time as public coverage expansions create additional avenues of coverage for children whose economic circumstances change.

A multivariate analysis of CTS data indicates that about one-fourth of the increase in public coverage among children in families with incomes less than 200 percent of poverty between 1997 and 2001 involved substitution of public coverage for private. 9 Among children in families with incomes between 100 percent and 200 percent of poverty (the primary SCHIP target group), about 39 percent of the increase in SCHIP or Medicaid involved substitution.

These estimates are consistent with earlier ones of the extent of substitution when Medicaid eligibility was expanded in the late 1980s and early 1990s (although estimates for the latter vary considerably due to different data and methods used to compute substitution). 10 Given the much higher rates of private coverage for the SCHIP target population, one might have expected substitution in SCHIP to be higher than in the previous Medicaid expansions. But substitution with SCHIP also might be lower because states are required to adopt explicit procedures for preventing switching from private to public coverage. While some states simply collect information on the amount of substitution with the implicit promise that they will act if it is found to be significant, others have implemented explicit measures, most commonly requirements that children be uninsured for a certain time period (typically three to six months) before being allowed to enroll in SCHIP or collecting information on previous insurance coverage.

Although the results show that there has been substitution of public for private coverage, this does not necessarily mean that the measures designed to prevent direct switching from private to public coverage have been ineffective. Rather, the substitution that occurred over the four-year period captured by the CTS surveys may be much more complex.

Studies have documented that movement into and out of various types of insurance is much more dynamic than is captured by surveys taking snapshots of coverage every one or two years, as with the CTS. 11 For example, some children experience temporary spells of being uninsured or being enrolled in Medicaid when a parent loses a job. In the absence of SCHIP, many of these children eventually might have returned to private insurance when their parents got new or better jobs or bought an individual insurance policy, but they remain enrolled in SCHIP instead. Most current crowd-out protections do not address this form of substitution.

![]() tates have begun to fulfill the vision of SCHIP to reduce the number of uninsured children. While expansion of public coverage has led to some displacement of private

insurance coverage, more recent gains indicate that the program is also reducing the number of uninsured children. However, the slow national economy, rising costs for private insurance coverage and growing state budget deficits threaten to block further progress or even erode gains made to date. 12

tates have begun to fulfill the vision of SCHIP to reduce the number of uninsured children. While expansion of public coverage has led to some displacement of private

insurance coverage, more recent gains indicate that the program is also reducing the number of uninsured children. However, the slow national economy, rising costs for private insurance coverage and growing state budget deficits threaten to block further progress or even erode gains made to date. 12

Faced with mounting deficits and growing Medicaid budgets, most states turned to cost containment first, including prescription drug cost controls, reducing or freezing provider payments, cutting benefits or increasing beneficiary copayments and reducing or restricting Medicaid eligibility. 13 SCHIP largely escaped any reduction in eligibility or benefits, although some states reduced their outreach efforts. 14

Rising unemployment and premium increases will decrease the availability and affordability of private insurance for many parents of low-income children. SCHIP and Medicaid provide an important safety net for children who lose private insurance coverage when their parents become unemployed, or when their parents can no longer afford the escalating costs of private insurance coverage. Thus, any reductions in eligibility due to state budget pressures will put more children at risk of losing coverage entirely.

![]() his Issue Brief presents findings from the HSC Community

Tracking Study Household Survey, a nationally representative telephone survey

of the civilian, noninstitutionalized population conducted in 1996-97, 1998-99

and 2000-01. For discussion and presentation, we refer to single calendar years

of the survey (1997, 1999 and 2001). Data were supplemented by in-person interviews

of households without telephones to ensure proper representation. Each round

of the survey contains information on about 60,000 people, including more than

10,000 children. The response rates for the surveys ranged from 59 percent to

65 percent.

his Issue Brief presents findings from the HSC Community

Tracking Study Household Survey, a nationally representative telephone survey

of the civilian, noninstitutionalized population conducted in 1996-97, 1998-99

and 2000-01. For discussion and presentation, we refer to single calendar years

of the survey (1997, 1999 and 2001). Data were supplemented by in-person interviews

of households without telephones to ensure proper representation. Each round

of the survey contains information on about 60,000 people, including more than

10,000 children. The response rates for the surveys ranged from 59 percent to

65 percent.

More detailed information on survey methodology can be found at www.hschange.org.

ISSUE BRIEFS are published by the Center for Studying Health System Change.

President: Paul B. Ginsburg

Director of Public Affairs: Richard Sorian

Editor: The Stein Group

For additional copies or to be added

to the mailing list, contact HSC at:

600 Maryland Avenue, SW

Suite 550

Washington, DC 20024-2512

Tel: (202) 554-7549

(for publication information)

Fax: (202) 484-5261

(for general HSC information)

www.hschange.org