Competition Revs Up the Indianapolis Health Care Market

Community Report No. 1

Winter 2003

Aaron Katz, Robert E. Hurley, Kelly Devers, Leslie Jackson Conwell, Bradley C. Strunk, Andrea Staiti, J. Lee Hargraves, Robert A. Berenson

n September 2002, a team of researchers visited Indianapolis to study that community’s

health system, how it is changing and the effects of those changes on consumers.

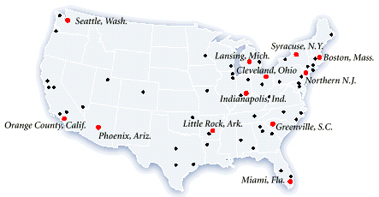

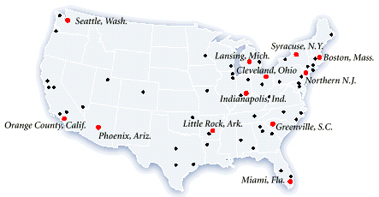

The Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC), as part of the Community Tracking Study, interviewed more than 100 leaders in the health care market. Indianapolis is one of 12 communities tracked by HSC every two years through site visits and every three years through surveys. Individual community reports are published for each round of site visits. The first three site visits to Indianapolis, in 1996, 1998 and 2000, provided the background against which changes are tracked. The Indianapolis market encompasses a nine-county region that includes Boone, Hamilton, Hancock,

Hendricks, Johnson, Madison, Marion, Morgan and Shelby counties.

Once a model of genteel competition, the Indianapolis health

care market appears on the verge of becoming a battleground among providers. Physician

specialists are exercising growing leverage with the market’s four hospital systems,

seeking a share of facility fees to offset historically stagnant professional

fees. In addition, a relatively weak health plan market seems relegated to serving

as a messenger for providers seeking higher payments. Stung by rising premiums,

employers feel powerless as provider competition heats up and the economy cools

down.

Among the key market trends:

n September 2002, a team of researchers visited Indianapolis to study that community’s

health system, how it is changing and the effects of those changes on consumers.

The Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC), as part of the Community Tracking Study, interviewed more than 100 leaders in the health care market. Indianapolis is one of 12 communities tracked by HSC every two years through site visits and every three years through surveys. Individual community reports are published for each round of site visits. The first three site visits to Indianapolis, in 1996, 1998 and 2000, provided the background against which changes are tracked. The Indianapolis market encompasses a nine-county region that includes Boone, Hamilton, Hancock,

Hendricks, Johnson, Madison, Marion, Morgan and Shelby counties.

Once a model of genteel competition, the Indianapolis health

care market appears on the verge of becoming a battleground among providers. Physician

specialists are exercising growing leverage with the market’s four hospital systems,

seeking a share of facility fees to offset historically stagnant professional

fees. In addition, a relatively weak health plan market seems relegated to serving

as a messenger for providers seeking higher payments. Stung by rising premiums,

employers feel powerless as provider competition heats up and the economy cools

down.

Among the key market trends:

- Single-specialty groups and hospitals have sought to bolster revenues by

developing six new specialty hospitals and expanding service areas.

- Concern is growing among providers that Anthem—long a dominant player

locally and now a national power—will flex its muscles in contract and

payment negotiations.

- The community’s health care safety net has grown stronger, thanks to state

funding and local leadership, but is threatened by state budget cuts.

Pursuit of Profits Shakes Up Provider Market

hysician and hospital ventures are disrupting the long stable

Indianapolis market, which has been characterized by four hospital systems with

mutually exclusive geographic niches. Since the late 1990s, physician specialty

groups have grown in size and strength and now have moved aggressively to compete

for a greater share of facility fees from inpatient and outpatient services. Local

cardiovascular surgery groups initiated discussions about building heart hospitals

with MedCath, a for-profit national firm. To stave off the potential loss of physicians

and their patients, hospital systems forged partner-ships with the specialists

to consolidate or expand heart surgery programs. By late 2002, each of the four

hospital systems was building or had opened a freestanding heart facility—two

as joint ventures with physicians.

The building binge did not stop with heart surgery:

hysician and hospital ventures are disrupting the long stable

Indianapolis market, which has been characterized by four hospital systems with

mutually exclusive geographic niches. Since the late 1990s, physician specialty

groups have grown in size and strength and now have moved aggressively to compete

for a greater share of facility fees from inpatient and outpatient services. Local

cardiovascular surgery groups initiated discussions about building heart hospitals

with MedCath, a for-profit national firm. To stave off the potential loss of physicians

and their patients, hospital systems forged partner-ships with the specialists

to consolidate or expand heart surgery programs. By late 2002, each of the four

hospital systems was building or had opened a freestanding heart facility—two

as joint ventures with physicians.

The building binge did not stop with heart surgery:

- Orthopedics Indianapolis, a large single-specialty

group, announced plans to build

its own orthopedic hospital to supplement

its existing freestanding surgery center.

- St. Vincent’s Hospital and Health System

opened a new children’s hospital to compete

with Clarian’s Riley Children’s Hospital

(affiliated with Indiana University), for

many years the only children’s hospital in

the market.

- Physician specialty groups were building

outpatient facilities alone or in conjunction

with hospitals as well as incorporating

more diagnostic and laboratory testing

into their own practices.

And the spree may not be over. Some market observers expressed concern that

oncologists will initiate discussions with a for-profit national company, spurring hospitals

to build additional outpatient cancer facilities that physicians would partly own.

Competition among hospitals also has been heating up and may be breaking down

the market’s exclusive geographic spheres of influence. Several hospital systems

announced plans to build new hospitals or make significant renovations to existing

facilities in areas where competing systems are located. Some of the construction

is designed to move services of flagship hospitals into more lucrative and faster-growing

areas, particularly outside the city of Indianapolis. Competition among hospitals

also has been spurred by ongoing friction between physicians from Indiana University

and Methodist Hospital, which merged in 1997 to form Clarian Health System. Many

physicians affiliated with Methodist have moved to other hospitals, fueling growth

in programs at these competitors and potentially undermining Clarian’s dominant

market position.

The newly competitive Indianapolis market is likely to have significant effects on consumers. New facilities and services could lead to greater access to providers (at least for privately insured patients), lower costs and higher clinical quality as providers manage care better and compete for patients. However, providers have little incentive to focus on care management in a market dominated by preferred provider organizations (PPOs) that pay discounted fee-for-service or case rates and that do not differentiate among providers based on performance. Indeed, improving clinical quality did not appear to be a driving force for new facilities or services. Given these market conditions, provider competition could, alternatively, result in higher use rates and costs. Competition over specialty services also could lure profitable services away from general hospitals, draining revenues needed to cross-subsidize less profitable services, including care for the uninsured.

The escalating competitive behavior observed among providers suggests that Indianapolis is a health care market in motion without private market or public

regulatory brakes. In some parts of the country, pressure from purchasers, health plan negotiators or state regulators might be expected to slow down or divert bricks-and-

mortar competition. However, the 2002 Indianapolis market revealed none of

these forces: employers have little leverage with health care providers; health plans

seem resigned to passing on providers’ demands for higher payments; and state

policy makers have few tools to influence expansion decisions, having long ago

repealed certificate-of-need laws.

Back to Top

Purchasers Face Rising Premiums, Weak Economy

mployers wield little power over the Indianapolis health care

market and have limited options in the face of a weak economy and steep health

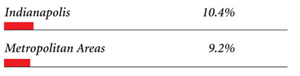

benefit cost increases. Insurance premiums began to rise in double digits in the

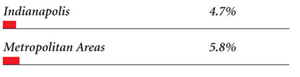

late 1990s. Unemployment was low then, about 2.6 percent, so businesses generally

absorbed these costs—rather than shift costs or cut benefits—to compete

for workers. However, unemployment in Indianapolis jumped to 4.6 percent in 2002,

a large increase though still below the national average of 5.8 percent. The higher

unemployment rate makes it easier for employers to increase employee cost sharing

or to explore more novel benefit strategies. In fact, faced with premium increases

of about 15 percent in 2002 and another 20 percent in 2003, employers in Indianapolis

are increasing deductibles and copayments, especially for prescription drug benefits,

and exploring consumer-driven health plans.

However, beyond cost-sharing changes, individual employers have not harnessed

their purchasing power to make demands of providers or plans. Public employers

have not been aggressive purchasers, while large private firms often have relationships

with health care organizations—such as serving on their boards—that

may blunt their ability to put pressure on the delivery system. For example, its

belief that improved quality will lower costs has spurred Eli Lilly over the years

to lead other large employers in collaborative efforts to improve the health care

delivery system. However, plan and provider respondents noted that Lilly must

proceed cautiously to avoid angering or alienating providers that purchase the

drug manufacturer’s products.

Although purchasers are not a significant force in Indianapolis, it is not for lack of trying. Since 1996, four different employer organizations have attempted to improve the health care delivery system. None of these organizations has had a sustained impact, in part because employers have had difficulties deciding among themselves what the goal of their efforts should be.

To make things worse, the weak economy has led to a decline in the number of corporate headquarters in Indianapolis: several large employers left the market, including the USA Group and Ameritech; the banking and insurance industries have consolidated; and Conseco, a financial services company in Carmel, declared bankruptcy at the end of 2002. The loss of headquarters may make it harder to develop effective coalitions that can shape the Indianapolis health care market. In all, this history led to a marked change in employer attitudes between 2000 and 2002, from being excited about the potential of their planned efforts to being more subdued and less optimistic about their ability to control costs.

Yet, employers are attempting once again to harness their power through the new Employers’ Forum, which aims to manage costs and promote employees’ involvement in health care decisions while also creating an environment that is responsive to the disparate needs of employers, providers and plans. What specific actions the forum will take was unclear in late 2002, and sustained buy-in from the employer community is uncertain.

mployers wield little power over the Indianapolis health care

market and have limited options in the face of a weak economy and steep health

benefit cost increases. Insurance premiums began to rise in double digits in the

late 1990s. Unemployment was low then, about 2.6 percent, so businesses generally

absorbed these costs—rather than shift costs or cut benefits—to compete

for workers. However, unemployment in Indianapolis jumped to 4.6 percent in 2002,

a large increase though still below the national average of 5.8 percent. The higher

unemployment rate makes it easier for employers to increase employee cost sharing

or to explore more novel benefit strategies. In fact, faced with premium increases

of about 15 percent in 2002 and another 20 percent in 2003, employers in Indianapolis

are increasing deductibles and copayments, especially for prescription drug benefits,

and exploring consumer-driven health plans.

However, beyond cost-sharing changes, individual employers have not harnessed

their purchasing power to make demands of providers or plans. Public employers

have not been aggressive purchasers, while large private firms often have relationships

with health care organizations—such as serving on their boards—that

may blunt their ability to put pressure on the delivery system. For example, its

belief that improved quality will lower costs has spurred Eli Lilly over the years

to lead other large employers in collaborative efforts to improve the health care

delivery system. However, plan and provider respondents noted that Lilly must

proceed cautiously to avoid angering or alienating providers that purchase the

drug manufacturer’s products.

Although purchasers are not a significant force in Indianapolis, it is not for lack of trying. Since 1996, four different employer organizations have attempted to improve the health care delivery system. None of these organizations has had a sustained impact, in part because employers have had difficulties deciding among themselves what the goal of their efforts should be.

To make things worse, the weak economy has led to a decline in the number of corporate headquarters in Indianapolis: several large employers left the market, including the USA Group and Ameritech; the banking and insurance industries have consolidated; and Conseco, a financial services company in Carmel, declared bankruptcy at the end of 2002. The loss of headquarters may make it harder to develop effective coalitions that can shape the Indianapolis health care market. In all, this history led to a marked change in employer attitudes between 2000 and 2002, from being excited about the potential of their planned efforts to being more subdued and less optimistic about their ability to control costs.

Yet, employers are attempting once again to harness their power through the new Employers’ Forum, which aims to manage costs and promote employees’ involvement in health care decisions while also creating an environment that is responsive to the disparate needs of employers, providers and plans. What specific actions the forum will take was unclear in late 2002, and sustained buy-in from the employer community is uncertain.

Back to Top

Weak Health Plan Market Belies Anthem’s Potential Power

ost health plans do not exercise much leverage with providers or strong managed care strategies, and observers expect little change in the near term, despite steeply rising premiums. As providers vie for new sources of revenue, they are pressuring health plans as well to increase payment rates to meet current and future financial needs, including the estimated $500 million in construction costs for new heart hospitals and other programs. Without employer pressure to counter these demands, most plans have found it difficult to resist hospitals’ and physicians’ push for higher payments. Instead, they increased beneficiary cost sharing to offset the impact of premium increases on employers.

Plans also are exploring new types of products to promote consumer cost-consciousness, such as high-deductible plans that require even greater levels of cost sharing and personal spending account-based

models. In addition, plans are evaluating tiered provider networks that would require consumers to pay more out-of- pocket to see higher-cost providers in the plan’s network. However, demand for broad, undifferentiated provider networks and resistance from hospitals may make such products unlikely in the short run.

Meanwhile, interest in health maintenance organizations (HMOs), never strong in

Indianapolis, has continued to decline, another indication of the deterioration

of health insurance products that could moderate prices in the market. Maxicare

declared bankruptcy in 2000 after a period of decline; Aetna aborted development

of its HMO in 2001; and Anthem’s HMO enrollment continues to shrink. As a result,

the only major HMOs available are those sponsored by the provider systems themselves.

Although these plans’ networks include nonowner hospitals, it is unlikely that

they have the same drive to moderate provider payment rates as independently owned

health plans. The financial well-being of HMOs has been threatened further by

a crisis in the state’s high-risk pool (see box on page 5).

As Indianapolis continues its long-standing preference for PPOs, Indianapolis-based Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield dominates the health plan market. Anthem maintains a large share of the market’s sizeable self-funded PPO business and accounts for the largest segment of the fully insured market, competing primarily with plans owned by the local provider systems.

Anthem’s local market presence has not changed appreciably, but its growing national

presence has heightened concern about the plan’s potential power in Indianapolis.

Anthem completed its con-version from a mutual insurance company to a publicly

traded firm in 2001 and became the fifth-largest health insurer in the country

by acquiring Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans in eight other states. The conversion

has generated some backlash among physicians who intensified com-plaints about

Anthem’s business practices, alleging down-coding—reclassifying claims to

codes with lower payment levels—and slow payment. Hospitals, too, have become

more assertive with Anthem. In 2002, St. Francis Hospital announced plans to terminate

its contract with Anthem over payment rates and contract terms, but the parties

later reached an agreement that includes quality-linked bonuses. To date, Anthem’s

potential power appears to be in check. However, if the plan becomes more aggressive

in its home market, pressure on provider payments could increase.

ost health plans do not exercise much leverage with providers or strong managed care strategies, and observers expect little change in the near term, despite steeply rising premiums. As providers vie for new sources of revenue, they are pressuring health plans as well to increase payment rates to meet current and future financial needs, including the estimated $500 million in construction costs for new heart hospitals and other programs. Without employer pressure to counter these demands, most plans have found it difficult to resist hospitals’ and physicians’ push for higher payments. Instead, they increased beneficiary cost sharing to offset the impact of premium increases on employers.

Plans also are exploring new types of products to promote consumer cost-consciousness, such as high-deductible plans that require even greater levels of cost sharing and personal spending account-based

models. In addition, plans are evaluating tiered provider networks that would require consumers to pay more out-of- pocket to see higher-cost providers in the plan’s network. However, demand for broad, undifferentiated provider networks and resistance from hospitals may make such products unlikely in the short run.

Meanwhile, interest in health maintenance organizations (HMOs), never strong in

Indianapolis, has continued to decline, another indication of the deterioration

of health insurance products that could moderate prices in the market. Maxicare

declared bankruptcy in 2000 after a period of decline; Aetna aborted development

of its HMO in 2001; and Anthem’s HMO enrollment continues to shrink. As a result,

the only major HMOs available are those sponsored by the provider systems themselves.

Although these plans’ networks include nonowner hospitals, it is unlikely that

they have the same drive to moderate provider payment rates as independently owned

health plans. The financial well-being of HMOs has been threatened further by

a crisis in the state’s high-risk pool (see box on page 5).

As Indianapolis continues its long-standing preference for PPOs, Indianapolis-based Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield dominates the health plan market. Anthem maintains a large share of the market’s sizeable self-funded PPO business and accounts for the largest segment of the fully insured market, competing primarily with plans owned by the local provider systems.

Anthem’s local market presence has not changed appreciably, but its growing national

presence has heightened concern about the plan’s potential power in Indianapolis.

Anthem completed its con-version from a mutual insurance company to a publicly

traded firm in 2001 and became the fifth-largest health insurer in the country

by acquiring Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans in eight other states. The conversion

has generated some backlash among physicians who intensified com-plaints about

Anthem’s business practices, alleging down-coding—reclassifying claims to

codes with lower payment levels—and slow payment. Hospitals, too, have become

more assertive with Anthem. In 2002, St. Francis Hospital announced plans to terminate

its contract with Anthem over payment rates and contract terms, but the parties

later reached an agreement that includes quality-linked bonuses. To date, Anthem’s

potential power appears to be in check. However, if the plan becomes more aggressive

in its home market, pressure on provider payments could increase.

Back to Top

Safety Net, Public Health Gains May be Lost as Budget Threat Looms

ven as provider competition sweeps through the market, Indianapolis’

safety net providers and public agencies have been a model of cooperation. As

was the case two years ago, leadership by the Health and Hospital Corporation

(HHC) of Marion County—including Wishard Health Services (the public Wishard

Hospital and six community health centers) and the Marion County Health Department—was

instrumental in these new cooperative efforts that have helped to strengthen the

safety net.

In 2000, safety net providers in Indianapolis anticipated that their capacity to serve low-income people would greatly expand soon due to public program expansions and the state’s decision to dedicate its tobacco settlement funds to health care. By 2002, this expectation had been well met. As a result of aggressive outreach and enrollment activities, the state’s Medicaid managed care program, Hoosier Healthwise, grew 12 percent in Marion County, from approximately 74,750 enrollees in June 2001 to 83,600 in June 2002. Moreover, the state mandated managed care for most Medicaid beneficiaries in Marion County, the first of five Indiana counties, beginning in April 2002, and HMO enrollment now exceeds 100,000. This enrollment growth meant safety net providers are getting paid

for care they previously provided for free. The state also awarded $31 million in tobacco settlement grants in that program’s first year, which both Wishard Health Services and the HealthNet clinic system

used to expand and modernize existing facilities and to build new ones.

Enrollment in Wishard Advantage—an innovative managed care program for uninsured

people operated by Wishard Health Services—grew by 50 percent in the first

10 months of 2002, expanding from 20,000 to 30,000 participants. The growth was

due to the economic downturn and the successful two-year effort to enlist participation

of all community health centers in Marion County. A federal grant to help integrate

systems of care for the uninsured bolstered this alliance further by developing

a common copayment policy across all of these safety net providers and making

available a prescription drug assistance program to all patients. Wishard also

used the grant to develop an electronic application system that will help enrollment

in Hoosier Healthwise and Wishard Advantage. These initiatives are widely seen

as improving provider bottom lines and stretching limited resources and capacities

as much as possible.

Adding to the sense of well-being in the public sector, Indianapolis-area leaders

have made substantial progress in preparing

for possible terrorist attacks, according to

local observers. Led by Indianapolis Mayor

Bart Peterson and the local health department,

these efforts reveal a high degree of

cooperation among local public agencies

and health care entities that are competing

in other arenas. Indianapolis’ readiness may

have been helped by the city’s earlier emergency

preparedness for such large events as

the Indianapolis 500 and an anthrax scare

before Sept. 11, 2001.

Despite this cooperation and progress, state budget difficulties now threaten safety net providers and access to care for low-income residents. The state ended fiscal year 2002 with the smallest reserve since 1993, having collected $300 million less in taxes than expected, and Medicaid spending was exceeding available revenue by about $250 million. On July 1, 2002, the state eliminated continuous eligibility for Medicaid; beneficiaries now must be recertified each time their financial status changes. The state has cut Medicaid

hospital payment rates by 5 percent in each of the last two years, pharmacy payments by $37 million and nursing home spending by $108 million. Some fear the lingering recession will lead lawmakers to enact

more provider cuts, limit certain Medicaid benefits, call off the aggressive outreach efforts that expanded coverage to many of the uninsured and/or use tobacco settlement funds to shore up the overall state budget

rather than specifically for health programs.

ven as provider competition sweeps through the market, Indianapolis’

safety net providers and public agencies have been a model of cooperation. As

was the case two years ago, leadership by the Health and Hospital Corporation

(HHC) of Marion County—including Wishard Health Services (the public Wishard

Hospital and six community health centers) and the Marion County Health Department—was

instrumental in these new cooperative efforts that have helped to strengthen the

safety net.

In 2000, safety net providers in Indianapolis anticipated that their capacity to serve low-income people would greatly expand soon due to public program expansions and the state’s decision to dedicate its tobacco settlement funds to health care. By 2002, this expectation had been well met. As a result of aggressive outreach and enrollment activities, the state’s Medicaid managed care program, Hoosier Healthwise, grew 12 percent in Marion County, from approximately 74,750 enrollees in June 2001 to 83,600 in June 2002. Moreover, the state mandated managed care for most Medicaid beneficiaries in Marion County, the first of five Indiana counties, beginning in April 2002, and HMO enrollment now exceeds 100,000. This enrollment growth meant safety net providers are getting paid

for care they previously provided for free. The state also awarded $31 million in tobacco settlement grants in that program’s first year, which both Wishard Health Services and the HealthNet clinic system

used to expand and modernize existing facilities and to build new ones.

Enrollment in Wishard Advantage—an innovative managed care program for uninsured

people operated by Wishard Health Services—grew by 50 percent in the first

10 months of 2002, expanding from 20,000 to 30,000 participants. The growth was

due to the economic downturn and the successful two-year effort to enlist participation

of all community health centers in Marion County. A federal grant to help integrate

systems of care for the uninsured bolstered this alliance further by developing

a common copayment policy across all of these safety net providers and making

available a prescription drug assistance program to all patients. Wishard also

used the grant to develop an electronic application system that will help enrollment

in Hoosier Healthwise and Wishard Advantage. These initiatives are widely seen

as improving provider bottom lines and stretching limited resources and capacities

as much as possible.

Adding to the sense of well-being in the public sector, Indianapolis-area leaders

have made substantial progress in preparing

for possible terrorist attacks, according to

local observers. Led by Indianapolis Mayor

Bart Peterson and the local health department,

these efforts reveal a high degree of

cooperation among local public agencies

and health care entities that are competing

in other arenas. Indianapolis’ readiness may

have been helped by the city’s earlier emergency

preparedness for such large events as

the Indianapolis 500 and an anthrax scare

before Sept. 11, 2001.

Despite this cooperation and progress, state budget difficulties now threaten safety net providers and access to care for low-income residents. The state ended fiscal year 2002 with the smallest reserve since 1993, having collected $300 million less in taxes than expected, and Medicaid spending was exceeding available revenue by about $250 million. On July 1, 2002, the state eliminated continuous eligibility for Medicaid; beneficiaries now must be recertified each time their financial status changes. The state has cut Medicaid

hospital payment rates by 5 percent in each of the last two years, pharmacy payments by $37 million and nursing home spending by $108 million. Some fear the lingering recession will lead lawmakers to enact

more provider cuts, limit certain Medicaid benefits, call off the aggressive outreach efforts that expanded coverage to many of the uninsured and/or use tobacco settlement funds to shore up the overall state budget

rather than specifically for health programs.

Back to Top

The Risky Business of High-Risk Pools

he Indiana Comprehensive Health Insurance Association (ICHIA)—Indiana’s

state-run high-risk pool—faced a financing crisis when assessments to cover

program costs mushroomed 77 percent between 2000 and 2002. State-run high-risk

pools have been created to provide access to health insurance for people who are

medically uninsurable. Generally, people pay premiums that are pegged to some

percentage above private market rates, and costs that exceed premium income are

covered by assessments against health plans. These insurance programs often struggle

financially, because costs grow faster than collected premiums.

This fate befell ICHIA when, after steady growth since 1992, costs skyrocketed

after the state used federal grant funds to enroll people with HIV/AIDS. Health

plan assessments reached about $80 million, causing financial stress for many

local plans. Part of the problem stemmed from the fact that ICHIA assessments

were based on a health plan’s share of premium revenues in the market, which applies

only to fully insured product offerings and ignores the large amount of revenue

in the self-funded market. As a result, plans whose business was primarily in

fully insured products—namely HMOs—shouldered a disproportionately

large share of the assessment burden.

Three HMOs sued the state over the pool’s funding method, and, in late 2002, the

ICHIA board revised the method to apportion assessments based on an insurer’s

share of covered lives rather than on premium revenue. This change is expected

to reduce the overall burden on insured HMOs and increase assessments paid by

stop-loss carriers, which protect self-insured employers against very large (catastrophic)

claims. However, the steep growth in ICHIA assessments reveals how fragile the

financing of state high-risk pools—and the economic well-being of the health

plans they rely on—can be.

he Indiana Comprehensive Health Insurance Association (ICHIA)—Indiana’s

state-run high-risk pool—faced a financing crisis when assessments to cover

program costs mushroomed 77 percent between 2000 and 2002. State-run high-risk

pools have been created to provide access to health insurance for people who are

medically uninsurable. Generally, people pay premiums that are pegged to some

percentage above private market rates, and costs that exceed premium income are

covered by assessments against health plans. These insurance programs often struggle

financially, because costs grow faster than collected premiums.

This fate befell ICHIA when, after steady growth since 1992, costs skyrocketed

after the state used federal grant funds to enroll people with HIV/AIDS. Health

plan assessments reached about $80 million, causing financial stress for many

local plans. Part of the problem stemmed from the fact that ICHIA assessments

were based on a health plan’s share of premium revenues in the market, which applies

only to fully insured product offerings and ignores the large amount of revenue

in the self-funded market. As a result, plans whose business was primarily in

fully insured products—namely HMOs—shouldered a disproportionately

large share of the assessment burden.

Three HMOs sued the state over the pool’s funding method, and, in late 2002, the

ICHIA board revised the method to apportion assessments based on an insurer’s

share of covered lives rather than on premium revenue. This change is expected

to reduce the overall burden on insured HMOs and increase assessments paid by

stop-loss carriers, which protect self-insured employers against very large (catastrophic)

claims. However, the steep growth in ICHIA assessments reveals how fragile the

financing of state high-risk pools—and the economic well-being of the health

plans they rely on—can be.

Back to Top

Issues to Track

he past two years have seen Indianapolis transformed from a stable, almost predictable market to a swirl of new construction and hotly contested service areas. This dramatic shift has been sparked by the efforts of

single-specialty medical groups to secure a larger portion of hospitals’ business and by hospital strategies to carve out new market niches. Moreover, providers of all types are demanding higher payments, ostensibly to recoup after years of stagnation. With health plan, employer and public policy sectors seemingly powerless to stop the concomitant surge in costs, consumers are absorbing higher cost sharing in the midst of a weak economy.

As the new competitive market unfolds,

these issues will be important to track:

he past two years have seen Indianapolis transformed from a stable, almost predictable market to a swirl of new construction and hotly contested service areas. This dramatic shift has been sparked by the efforts of

single-specialty medical groups to secure a larger portion of hospitals’ business and by hospital strategies to carve out new market niches. Moreover, providers of all types are demanding higher payments, ostensibly to recoup after years of stagnation. With health plan, employer and public policy sectors seemingly powerless to stop the concomitant surge in costs, consumers are absorbing higher cost sharing in the midst of a weak economy.

As the new competitive market unfolds,

these issues will be important to track:

- How will the new specialty facilities affect

the cost, quality and availability of health

care in Indianapolis? Will they draw

profitable business away from general

community hospitals, thus hampering

their ability to provide unprofitable

services and charity care?

- How will state budget difficulties affect

the recent progress and growth in public

insurance programs and continuing

support for the safety net? Will low-income

residents be left with less access

to needed care?

- Can health plans and employers find the

market muscle to control spending and

premium growth? If not, how will higher

cost sharing affect consumers?

- Will the newly formed Employers’ Forum have any greater success than similar

past efforts in influencing provider and plan performance in the Indianapolis

marketplace?

Back to Top

Indianapolis Consumers’ Access to Care, 2000

Indianapolis compared to metropolitan areas with over 200.000 population

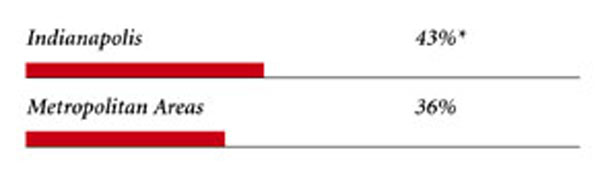

| Unmet Need |

| PERSONS WHO DID NOT GET NEEDED MEDICAL CARE DURING THE LAST 12 MONTHS |

|

| Delayed Care |

| PERSONS WHO DELAYED GETTING NEEDED MEDICAL CARE DURING THE LAST 12 MONTHS

|

|

| Out-of-Pocket Costs |

| PRIVATELY INSURED PEOPLE IN FAMILIES WITH ANNUAL OUT-OF-POCKET

COSTS OF $500 OR MORE |

|

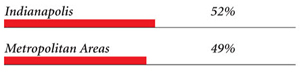

| Access to Physicians |

| PHYSICIANS WILLING TO ACCEPT ALL NEW PATIENTS WITH PRIVATE

INSURANCE |

|

| PHYSICIANS WILLING TO ACCEPT ALL NEW MEDICARE PATIENTS |

|

| PHYSICIANS WILLING TO ACCEPT ALL NEW MEDICAID PATIENTS |

|

| PHYSICIANS PROVIDING CHARITY CARE |

|

* Site value is significantly different from the mean for large metropolitan

areas over 200,000 population at p<.05.

Source: HSC Community Tracking Study Household and

Physician Surveys, 2000-01

Note: If a person reported both

an unmet need and delayed care, that person is counted as having an unmet

need only. Based on follow-up questions asking for reasons for unmet needs

or delayed care, data include only responses where at least one of the reasons

was related to the health care system. Responses related only to personal

reasons were not considered as unmet need or delayed care. |

Back to Top

Background and Observations

| Indianapolis Demographics |

| Indianapolis |

Metropolitan areas 200,000+ population |

Population1

1,620,373 |

| Persons Age 65 or Older2 |

| 11% |

11% |

| Median Family Income3 |

| $30,745 |

$31,883 |

| Unemployment Rate3 |

| 4.5% |

5.8% |

| Persons Living in Poverty2 |

| 8% |

12% |

| Persons Without Health Insurance2

|

| 12% |

13% |

| Age-Adjusted Mortality Rate per 1,000 Population4

|

| 9.8 |

8.8* |

* National average.

Sources:

1. U.S. Census Bureau, County Population Estimates, July 1, 2001

2. HSC Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 2000-01

3. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2002 (site estimate calculated by taking

the average of monthly unemployment rates, January-December 2002)

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1999 |

| Health Care Utilization |

| Indianapolis |

Metropolitan areas above 200,000 population |

| Adjusted Inpatient Admissions per 1,000 Population 1 |

| 225 |

180 |

| Persons with Any Emergency Room Visit in Past Year 2

|

| 20% |

19% |

| Persons with Any Doctor Visit in Past Year 2 |

| 79% |

78% |

| Average Number of Surgeries in Past Year per 100 Persons 2 |

| 18 |

17 |

Sources:

1. American Hospital Association, 2000

2. HSC Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 2000-01 |

| Health System Characteristics |

| Indianapolis |

Metropolitan areas 200,000+ population |

| Staffed Hospital Beds per 1,000 Population1

|

| 3.0 |

2.5 |

| Physicians per 1,000 Population2

|

| 2.0 |

1.9 |

| HMO Penetration, 19993 |

| 23% |

38% |

| HMO Penetration, 20014 |

| 21% |

37% |

| Medicare-Adjusted Average per Capita Cost

(AAPCO) Rate, 20023 |

| $553 |

$575 |

Sources:

1. American Hospital Association, 2000

2. Area Resource File, 2002 (includes nonfederal, patient care physicians, except radiologists, pathologists and anesthesiologists)

3. InterStudy Competitive Edge, 10.1

4. InterStudy Competitive Edge, 11.2

5. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Site estimate is payment

rate for largest county in site; national estimate is national per capita

spending on Medicare enrollees in Coordinated Care Plans in December 2002.

|

Back to Top

The Community Tracking Study, the major effort of the Center for Studying Health

System Change (HSC), tracks changes in the health system in 60 sites that are

representative of the nation. HSC conducts surveys in all 60 communities every

three years and site visits in 12 communities every two years. This Community

Report series documents the findings from the fourth round of site visits. Analyses

based on site visit and survey data from the Community Tracking Study are published

by HSC in Issue Briefs, Tracking Reports, Data Bulletins and peer-reviewed journals.

These publications are available at

www.hschange.org.

Authors of the Indianapolis Community Report:

Aaron Katz, University of Washington; Robert E. Hurley, Virginia Commonwealth

University;

Kelly J. Devers, HSC; Leslie A. Conwell, HSC; Bradley C. Strunk, HSC; Andrea

B. Staiti, HSC;

J. Lee Hargraves, HSC; Robert A. Berenson, AcademyHealth

Community Reports are published by HSC:

President: Paul B. Ginsburg

Director of Site Visits: Cara S. Lesser

Director of Public Affairs: Richard Sorian

Editor: The Stein Group

For additional copies or to be added to the mailing list, contact HSC at:

600 Maryland Avenue SW, Suite 550, Washington, DC 20024-2512

Tel: (202) 554-7549 (for publication information)

Tel: (202) 484-5261 (for general HSC information)

Fax: (202) 484-9258

www.hschange.org