Community Report No. 3

Winter 2003

Glen P. Mays, Sally Trude, Lawrence P. Casalino, Laurie E. Felland, Gary Claxton, Hoangmai H. Pham, Lydia E. Regopoulos, Aaron Katz, Kyle Kinner

Seattle’s current health care market stands in stark contrast to two years ago when Washington’s generous public insurance programs were expanding and employers offered rich benefits to attract and retain workers in a tight labor market. A sharp downturn in the local economy and escalating health care costs have caused a state budget crisis that threatens to unravel much of the progress made in expanding health insurance coverage. These same pressures have contributed to continuing tense relationships between health plans and providers, leading consumers to worry about losing access to providers of choice.

Other significant developments include:

- State Budget Woes Force Cuts

- Safety Net Capacity Stretched

- Employers Eye New Health Plan Designs to Contain Costs

- Consumers Still Concerned About Network Stability

- Quality Initiatives Gain Momentum

- Providers Expand Profitable Specialty Services

- Issues to Track

- Seattle Consumers’ Access to Care, 2001

- Background and Observations

State Budget Woes Force Cuts

![]() fter years of expanding public health insurance coverage,

state policy makers have retrenched in response to a growing state budget deficit

and rising health care costs. State tax revenues have dropped precipitously because

of the economic downturn, creating a deficit of about $2 billion for the next

two-year budget cycle, starting July 2003. State health programs funded at current

levels—including Washington’s Medicaid program, the Children’s Health Insurance

Program (CHIP) and the Basic Health Plan, a state-sponsored insurance program

for low-income people who do not have access to other sources of coverage—account

for 35 percent to 40 percent of the projected deficit, according to a legislative

appropriations committee.

fter years of expanding public health insurance coverage,

state policy makers have retrenched in response to a growing state budget deficit

and rising health care costs. State tax revenues have dropped precipitously because

of the economic downturn, creating a deficit of about $2 billion for the next

two-year budget cycle, starting July 2003. State health programs funded at current

levels—including Washington’s Medicaid program, the Children’s Health Insurance

Program (CHIP) and the Basic Health Plan, a state-sponsored insurance program

for low-income people who do not have access to other sources of coverage—account

for 35 percent to 40 percent of the projected deficit, according to a legislative

appropriations committee.

The current budget crisis stems in part from the notable success of state and local efforts to expand health coverage over the past decade. Washington has generous eligibility standards for Medicaid and CHIP—250 percent of the federal poverty level for children—and has expanded the Basic Health Plan to cover individuals with no other access to insurance up to 200 percent of the poverty level. The state had hoped to receive additional federal funding in 2002 to help pay for these newly enrolled populations, but it netted nearly $800 million less than expected.

In response, the state has discontinued outreach funding for Medicaid, CHIP and the Basic Health Plan, and it has eliminated Medicaid and CHIP coverage for about 28,000 immigrants, requiring them to seek coverage under the Basic Health Plan, instead. Additionally, the state has proposed shelving a planned eligibility expansion of the Basic Health Plan—called for by a 2001 ballot initiative that increased tobacco taxes—and, instead, has committed most of the new revenue to fund current Basic Health Plan obligations. Finally, the state has applied for a federal Medicaid waiver that could save up to $50 million annually by requiring premiums for some beneficiaries, increasing copayments and allowing the state to freeze Medicaid and CHIP enrollment.

Community leaders and various stakeholders agreed the state has tried to minimize fallout for low-income people, but state actions so far have done little to eliminate the projected shortfall, leading most observers to conclude more severe cuts are on the horizon. With no clear consensus about solutions, many observers feared funding for safety net providers and public programs will decline just as the needs of low-income people increase. For example, some expect that significant numbers of the immigrants cut from Medicaid eligibility will fail to enroll in the Basic Health Plan, thereby fueling growth in the uninsured population and further straining safety net providers.

Some policy makers see an opportunity to support health care initiatives across the state by using the proceeds of a planned conversion to for-profit status of Premera Blue Cross, one of the state’s two not-for-profit Blues plans. Although this could provide state and local health programs with a much-needed funding infusion, many policy makers and advocates are reluctant to embrace this proposal because they fear conversion will prompt higher insurance premiums down the road. The state insurance department must still approve the conversion.

Safety Net Capacity Stretched

![]() ccording to most community leaders and stakeholders, despite progress in enrolling eligible people in public insurance programs, the number of uninsured Seattle residents has grown over the past two years, presenting challenges to Seattle’s safety net providers. The combined effect of rising unemployment,

declining real wages and rising health costs has increased demand for charity care and public programs among Seattle’s uninsured and underinsured residents.

ccording to most community leaders and stakeholders, despite progress in enrolling eligible people in public insurance programs, the number of uninsured Seattle residents has grown over the past two years, presenting challenges to Seattle’s safety net providers. The combined effect of rising unemployment,

declining real wages and rising health costs has increased demand for charity care and public programs among Seattle’s uninsured and underinsured residents.

Seattle’s safety net providers have expanded capacity to serve the uninsured and other underserved populations,although access to some specialty services remains limited. Additional federal funds have helped. Five of Seattle’s community health centers received federal grants in 2002 totaling almost $900,000, allowing them to upgrade facilities and offer, for example, mental health services. The community health centers also have attracted a steady revenue stream by serving Medicaid, CHIP and Basic Health Plan members.

More recently, however, safety net providers have begun to face challenges due to funding reductions and the reduced participation of private providers in serving low-income populations. Budget deficits are forcing local governments to cut safety net health care spending significantly in 2003, while the state plans to move away from cost-based Medicaid reimbursement for community health centers in response to recent federal legislation.

At the same time, Seattle’s mainstream physicians and hospitals are scaling back charity care and participation in publicly funded programs, including Medicaid, the Basic Health Plan and, to a lesser extent, Medicare. Concerned about low payment rates and administrative requirements associated with these programs, these mainstream providers have limited the number of public-pay patients they accept—particularly new patients—and, in some cases, stopped serving these patients altogether. Moreover, low payment rates, along with rising practice expenses, have eroded physicians’ ability to cross-subsidize charity care for the uninsured. One traditional source of specialty care for the uninsured—the PacMed Clinics—expected to reduce charity care by as much as 40 percent as part of its transition from a quasi-governmental entity to a not-for-profit corporation.

The net effect of these changes on access to care for underserved people largely remains to be seen. Nevertheless, Seattle’s health care safety net likely will be challenged to provide care for larger numbers of uninsured and publicly insured residents with fewer resources available to support this care.

Employers Eye New Health Plan Designs to Contain Costs

![]() istorically, Seattle’s employers have offered generous

health benefits with relatively little of the consumer cost sharing seen in

other markets across the country—a phenomenon driven by Seattle’s large

presence of public employers and unionized industries. However, the economic

downturn, along with rising health insurance premiums, has led employers to

increase copayments and deductibles for workers, and many public and unionized

employers, for the first time, now require employees to contribute to premiums.

Coupled with wage freezes, the changes have reduced net pay for many workers.

istorically, Seattle’s employers have offered generous

health benefits with relatively little of the consumer cost sharing seen in

other markets across the country—a phenomenon driven by Seattle’s large

presence of public employers and unionized industries. However, the economic

downturn, along with rising health insurance premiums, has led employers to

increase copayments and deductibles for workers, and many public and unionized

employers, for the first time, now require employees to contribute to premiums.

Coupled with wage freezes, the changes have reduced net pay for many workers.

Employer efforts to increase consumer cost sharing have prompted health plans to modify their standard health insurance products. In preferred provider organization (PPO) products, which have dominated Seattle’s insurance market for much of the past decade, plans are moving away from generous benefit packages. Instead of offering benefit structures similar to those in health maintenance organizations (HMOs), with low, fixed copayments and no deductibles, PPOs are moving toward more conventional benefit designs with significant deductibles and coinsurance, where patients pay a percentage of the bill rather than a fixed-dollar amount. Even Group Health Cooperative, the area’s oldest and largest HMO, recently began offering HMO products with deductible and coinsurance options to slow the rise in employer premiums.

While employers are using the short-term tactic of increased cost sharing,many also are looking for longer-term strategies to reduce costs and use of services. Seattle health plans have developed an array of new products to give purchasers and consumers a choice of lower-cost benefit designs and provider networks. Premera Blue Cross, one of the state’s largest insurers, introduced a tiered-network product offering a choice of consumer cost-sharing levels and different provider networks determined by the cost and efficiency of the providers.

Regence BlueShield and Aetna US Healthcare launched consumer-directed health plans that give consumers a personal spending account to use for initial health care costs, after which deductibles and coinsurance requirements apply.

Although Seattle’s employers are increasingly interested in new strategies for containing health insurance costs, relatively few had purchased the new product offerings to date. Many employers were skeptical that consumer-driven health plans and tiered-network products were practical for their workforce. They questioned the ability of employees to access and understand information about the choices and costs within the new designs as well as the feasibility of administering complex benefit designs and provider networks within large, multisite employers.

In addition, tiered-network products face some important operational challenges, according to employers and other observers, including problems differentiating among providers based on efficiency and quality with available data and methods. Some respondents also suggest that the development of tiered networks has been complicated by the ability of providers to use their negotiating leverage and political influence to avoid placement in nonpreferred tiers. However, health plan executives contend that difficulties in creating tiers reflect the fact that providers are adopting pricing strategies that allow them to remain in preferred tiers—a response that helps the plan to achieve some cost control.

Consumers Still Concerned About Network Stability

![]() elationships between health plans and Seattle’s hospital

systems and large medical groups have remained tense as all strive to remain

profitable amid rapidly rising costs. Two years ago, Seattle’s health plans

experienced considerable provider network disruptions because of contracting

disputes with major physician groups and hospital systems, the unraveling of

several large independent practice associations (IPAs) and a growing aversion

among providers to risk-based contracting with HMOs. These disruptions caused

considerable anxiety for consumers concerned about maintaining in-network access

to their providers of choice. Since then, Seattle’s two largest health plans—Regence

BlueShield and Premera Blue Cross, both hard hit by contract disputes in 1999

and 2000—have attempted to improve relations with providers by offering

higher payment rates, more flexible payment methods and a more collaborative

approach to negotiations.

elationships between health plans and Seattle’s hospital

systems and large medical groups have remained tense as all strive to remain

profitable amid rapidly rising costs. Two years ago, Seattle’s health plans

experienced considerable provider network disruptions because of contracting

disputes with major physician groups and hospital systems, the unraveling of

several large independent practice associations (IPAs) and a growing aversion

among providers to risk-based contracting with HMOs. These disruptions caused

considerable anxiety for consumers concerned about maintaining in-network access

to their providers of choice. Since then, Seattle’s two largest health plans—Regence

BlueShield and Premera Blue Cross, both hard hit by contract disputes in 1999

and 2000—have attempted to improve relations with providers by offering

higher payment rates, more flexible payment methods and a more collaborative

approach to negotiations.

Although these two local insurers succeeded in stabilizing their provider networks, Seattle had another major contract dispute in 2001 when one of the area’s most popular hospital systems, Swedish Health Services, terminated its contract with Aetna after the insurer refused requested rate increases. Because Swedish is the dominant downtown Seattle hospital system and popular for maternity services, it is an important network component for health plans. Strong ties with physician groups such as PacMed, the Polyclinic and Minor and James added to concerns about Swedish’s inclusion in Aetna’s network.

Because Aetna is a leading insurer among Seattle’s large self-funded employers,many of the area’s most prominent businesses reportedly became involved in the dispute, including Nordstrom,Microsoft, Boeing, Starbucks, the city of Seattle and King County. While some employers applauded Aetna for aggressively fighting price increases of a hospital system with considerable negotiating leverage, other employers blamed Aetna for the network disruption. Ultimately, Swedish and Aetna reached agreement, but the contentious and protracted negotiations intensified consumer fears about losing access to providers of choice. Observers had conflicting views about whether Aetna was successful in securing lower rates from Swedish, because neither party disclosed the new contract terms.

Local observers suggest that a combination of factors has left Seattle’s health plans vulnerable to network instability problems, including consolidation of hospital systems and selected single-specialty medical groups and the continued consumer and employer demand for broad provider networks. Some plans, exemplified by Seattle’s local Blues insurers, appear to have abandoned hard-line negotiations as a cost-containment strategy, at least for the time being, to preserve broad and stable provider networks. Premera’s request to convert to for-profit status, however, has raised concerns among hospitals and physicians that such a move could lead the insurer to become more aggressive in contract negotiations, further compromising relationships between health plans and providers. For these reasons, the state’s hospital and medical associations have opposed the conversion.

Quality Initiatives Gain Momentum

![]() ospitals and employers have spearheaded health care quality and patient safety

initiatives in Seattle. All three of Seattle’s major downtown hospital systems have patient

safety programs in place, and Seattle was the first market where 100 percent of local

hospitals responded to a survey on patient safety activities initiated by the Leapfrog

Group, a national coalition of large purchasers. Leapfrog has undertaken strategies to

reduce medical errors and improve patient safety in hospitals. Areas of focus include

medication safety, intensive care units and data collection and reporting activities.

ospitals and employers have spearheaded health care quality and patient safety

initiatives in Seattle. All three of Seattle’s major downtown hospital systems have patient

safety programs in place, and Seattle was the first market where 100 percent of local

hospitals responded to a survey on patient safety activities initiated by the Leapfrog

Group, a national coalition of large purchasers. Leapfrog has undertaken strategies to

reduce medical errors and improve patient safety in hospitals. Areas of focus include

medication safety, intensive care units and data collection and reporting activities.

None of Seattle’s hospitals has fully met the Leapfrog standard of implementing a computerized physician order entry system; 18 percent have met the standard of staffing intensive care units with intensivists; and half have met the volume-based referral standard. Boeing, the machinists’ union and others are working with hospitals on the Leapfrog effort, and, in the future, Boeing plans to test a health plan design requiring employees to pay more if they use providers that do not comply with Leapfrog criteria.

Seattle’s major health plans vary considerably in how they approach patient safety and health care quality issues. For example, Group Health Cooperative has a long history of sponsoring programs to reduce medical errors (including Leapfrog standards) and improve clinical quality of care in both hospital settings and its multi-specialty physician group practice.More recently, Regence BlueShield has begun to publish Leapfrog hospital survey results on its Web site and has signed contracts with some employers guaranteeing to increase the proportion of hospitals in its network to meet Leapfrog standards.

Providers Expand Profitable Specialty Services

![]() eattle’s medical groups and hospital systems are pursuing

increased revenue through delivery of profitable ancillary and specialty services—a

practice that threatens to accelerate health care cost increases. Medical groups

are actively building capacity to deliver radiology, laboratory and imaging

services within their practices. Moreover, physician ventures to develop freestanding

ambulatory surgery and diagnostic centers—so they can capture the facility

payments associated with these services—have increased significantly.

Physicians often start these centers in competition with hospitals but also

sometimes in partnership with hospitals.

eattle’s medical groups and hospital systems are pursuing

increased revenue through delivery of profitable ancillary and specialty services—a

practice that threatens to accelerate health care cost increases. Medical groups

are actively building capacity to deliver radiology, laboratory and imaging

services within their practices. Moreover, physician ventures to develop freestanding

ambulatory surgery and diagnostic centers—so they can capture the facility

payments associated with these services—have increased significantly.

Physicians often start these centers in competition with hospitals but also

sometimes in partnership with hospitals.

A small but increasingly visible number of Seattle physicians have abandoned traditional medical practices altogether and developed concierge care practices that offer patients priority access in exchange for a retainer paid by the patient, ranging from $700 to $20,000 a year. Several health plans view concierge care as a mechanism for physician balance billing—a practice prohibited under health plan contracts—so they refuse to list these physicians in their provider directories.

Physicians have pursued profitable services partly in response to mounting financial pressures created by staffing shortages, rising malpractice insurance premiums and low reimbursement rates from government programs. Elimination of health plans’ prior authorization requirements and the demise of risk contracting also contributed to the growth in ancillary service use. Additionally, one of Seattle’s largest insurers acknowledged that past success in holding down physician payments for professional services may have driven physicians to expand their revenue base through increased use of ancillary services and more ownership of the facilities and equipment needed to provide them.

For similar reasons, Seattle’s hospitals have continued to compete aggressively for patients and revenue in profitable inpatient and outpatient service lines, including cardiology, oncology, neurosurgery, orthopedics and neonatal intensive care. Suburban hospitals have upgraded specialty capacities in an attempt to retain suburban patients, while downtown hospitals are competing to attract suburban patients. This hospital competition is particularly intense for cardiology and neonatal intensive care services, which both yield lucrative payments from commercial insurers and public programs.

In some cases, downtown and suburban hospitals have formed alliances to expand these services. For example, in 2002, suburban Evergreen Healthcare became the fourth area hospital to open a neonatal intensive care unit, partnering with the University of Washington Medical Center, and two other suburban hospitals plan to open such facilities. Hospitals also are actively developing ambulatory surgery and diagnostic facilities in the rapidly growing Seattle suburbs, partnering with medical groups where necessary to prevent loss of revenue to physician-owned facilities.

Although hospital and physician efforts to build capacity in profitable service areas partly reflect the growing demand for these services in Seattle, many observers worry that the rapid buildup will result in excess capacity and unsustainable rates of health care cost growth in the future. Despite these concerns, Seattle’s public and private stakeholders have yet to devise a clear strategy for constraining the growth in specialty and ancillary care capacity.

Issues to Track

![]() eattle’s struggling local economy and

rapidly rising health care costs, coupled

with the state budget crisis, threaten to

unravel much of the progress of the 1990s

in expanding health insurance coverage.

In an effort to rein in costs, employers are

raising consumer cost-sharing requirements,

while health plans are experimenting with

new product designs. Meanwhile, Seattle’s

physician groups and hospital systems have

accelerated expansion into profitable specialty

and ancillary services, raising questions about

how health care costs can be contained in

the future.

eattle’s struggling local economy and

rapidly rising health care costs, coupled

with the state budget crisis, threaten to

unravel much of the progress of the 1990s

in expanding health insurance coverage.

In an effort to rein in costs, employers are

raising consumer cost-sharing requirements,

while health plans are experimenting with

new product designs. Meanwhile, Seattle’s

physician groups and hospital systems have

accelerated expansion into profitable specialty

and ancillary services, raising questions about

how health care costs can be contained in

the future.

Key issues include:

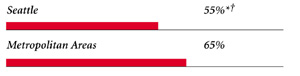

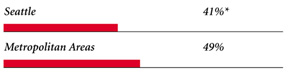

Seattle Consumers’ Access to Care, 2001

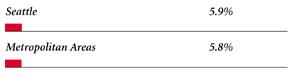

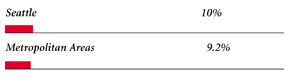

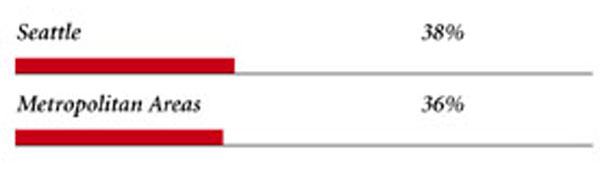

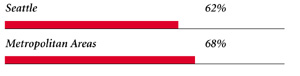

Seattle compared to metropolitan areas with over 200.000 population

| Unmet Need |

| PERSONS WHO DID NOT GET NEEDED MEDICAL CARE DURING THE LAST 12 MONTHS |

|

| Delayed Care |

| PERSONS WHO DELAYED GETTING NEEDED MEDICAL CARE DURING THE LAST 12 MONTHS |

|

| Out-of-Pocket Costs |

| PRIVATELY INSURED PEOPLE IN FAMILIES WITH ANNUAL OUT-OF-POCKET COSTS OF $500 OR MORE |

|

| Access to Physicians |

| PHYSICIANS WILLING TO ACCEPT ALL NEW PATIENTS WITH PRIVATE INSURANCE |

|

| PHYSICIANS WILLING TO ACCEPT ALL NEW MEDICARE PATIENTS |

|

| PHYSICIANS WILLING TO ACCEPT ALL NEW MEDICAID PATIENTS |

|

| PHYSICIANS PROVIDING CHARITY CARE |

|

| * Site value is significantly different from the mean for large metropolitan

areas over 200,000 population at p<.05. # Indicates a 12-site low. Source: HSC Community Tracking Study Household and Physician Surveys, 2000-01 Note: If a person reported both an unmet need and delayed care, that person is counted as having an unmet need only. Based on follow-up questions asking for reasons for unmet needs or delayed care, data include only responses where at least one of the reasons was related to the health care system. Responses related only to personal reasons were not considered as unmet need or delayed care. |

Background and Observations

| Seattle Demographics | |

| Seattle | Metropolitan areas 200,000+ population |

| Population1 2,438,799 |

|

| Persons Age 65 or Older2 | |

| 10% | 11% |

| Median Family Income2 | |

| $43,389 | $31,883 |

| Unemployment Rate3 | |

| 6.5% | 5.8% |

| Persons Living in Poverty2 | |

| 7.4% | 12% |

| Persons Without Health Insurance2 | |

| 7.9% | 13% |

| Age-Adjusted Mortality Rate per 1,000 Population4 | |

| 7.9 | 8.8* |

* National average. Sources: |

|

| Health Care Utilization | |

| Seattle | Metropolitan areas 200,000 population |

| Adjusted Inpatient Admissions per 1,000 Population 1 | |

| 149 | 180 |

| Persons with Any Emergency Room Visit in Past Year 2 | |

| 16% | 19% |

| Persons with Any Doctor Visit in Past Year 2 | |

| 80% | 78% |

| Average Number of Surgeries in Past Year per 100 Persons 2 | |

| 15 | 17 |

| Sources: 1. American Hospital Association, 2000 2. HSC Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 2000-01 |

|

| Health System Characteristics | |

| Seattle | Metropolitan areas 200,000+ population |

| Staffed Hospital Beds per 1,000 Population1 | |

| 1.7 | 2.5 |

| Physicians per 1,000 Population2 | |

| 2.1 | 1.9 |

| HMO Penetration, 19993 | |

| 20% | 38% |

| HMO Penetration, 20014 | |

| 18% | 37% |

| Medicare-Adjusted Average per Capita Cost (AAPCO) Rate, 20025 | |

| $553 | $575 |

| Sources: 1. American Hospital Association, 2000 2. Area Resource File, 2002 (includes nonfederal, patient care physicians, except radiologists, pathologists and anesthesiologists) 3. InterStudy Competitive Edge, 10.1 4. InterStudy Competitive Edge, 11.2 5. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Site estimate is payment rate for largest county in site; national estimate is national per capita spending on Medicare enrollees in Coordinated Care Plans in December 2002. |

|