Community Report No. 5

Spring 2003

Aaron Katz, Robert E. Hurley, Kelly Devers, Leslie Jackson Conwell, Bradley C. Strunk, Andrea Staiti, J. Lee Hargraves, Robert A. Berenson

A last-minute, temporary agreement during an acrimonious showdown between Lansing’s largest health plan and its biggest hospital prevented a major dislocation of patients and disruption of an otherwise stable health market in 2002.Much of this stability reflects the dominance of Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Michigan (BCBSM), which controls 70 percent of the private market in Lansing and largely determines hospital payment rates across the state. Lansing has avoided the hospital building booms and intense inflationary pressures experienced elsewhere in the United States, in part because of highly concentrated hospital and insurance sectors and long-standing support for state regulation.

Among key market trends:Blue Cross Confronts Market, Political Challenges

![]() CBSM controls about 70 percent of the privately insured

market in Lansing, a position it has enjoyed for many years. Although it faces

some competition, particularly in the health maintenance organization (HMO)

market from the Sparrow Health System-owned Physicians’ Health Plan (PHP), BCBSM’s

major challenges over the past two years stem from its special role in state

law and politics. In essence, both public policy makers and the area’s three

major employers—Michigan State University (MSU), the state of Michigan

and General Motors—rely heavily on BCBSM to act on their behalf to control

health care costs, improve quality and insure people with high medical costs.

This role is reinforced by the Blues’ board of directors, which includes among

its 35 members employers, unions, providers and public representatives.

CBSM controls about 70 percent of the privately insured

market in Lansing, a position it has enjoyed for many years. Although it faces

some competition, particularly in the health maintenance organization (HMO)

market from the Sparrow Health System-owned Physicians’ Health Plan (PHP), BCBSM’s

major challenges over the past two years stem from its special role in state

law and politics. In essence, both public policy makers and the area’s three

major employers—Michigan State University (MSU), the state of Michigan

and General Motors—rely heavily on BCBSM to act on their behalf to control

health care costs, improve quality and insure people with high medical costs.

This role is reinforced by the Blues’ board of directors, which includes among

its 35 members employers, unions, providers and public representatives.

BCBSM’s special responsibilities were highlighted by a clash with Sparrow Health System that came to a head in late 2002. Hoping to capitalize on its nearly two-thirds market share and unique service lines, Sparrow threatened to allow its BCBSM contract to expire on December 31, unless payment rates were increased significantly above the 3 percent hike the health plan offered. But the BCBSM offer was based on a participating hospital agreement (PHA) that for years has been the basic framework for Blue Cross and Blue Shield’s hospital contracts statewide. The PHA includes a model contract, developed with input from the state hospital association, that describes how hospitals will be compensated for treating BCBSM subscribers and stipulates a process—managed jointly by BCBSM, the hospital association and three independent appointees of the governor and legislature—that acts as a starting point to guide annual increases.

Sparrow reportedly demanded considerably more than suggested by the PHA guidance, arguing that BCBSM underestimated the cost of caring for its members and a larger increase was needed to make up for losses from Medicare and Medicaid. BCBSM contended that it was not responsible for underpayments by other payers and that Sparrow’s costs are relatively high and its calculations flawed. The health plan proposed bringing in an independent outside auditor to establish the cost of care.

Unlike other plan-provider disputes, Blue Cross and Blue Shield had the strong support of some local employers, public purchasers and residents. Employers, who wanted their rate increases curbed, supported BCBSM through public and private statements. Some Lansing firms also refused to reopen enrollment periods for employees who might then switch from Blue Cross and Blue Shield to another plan. Local residents did not want Sparrow to leave the BCBSM provider network, because that would have required as many as 67,000 people to shift from their usual source of medical care.

Moreover, the Lansing dispute followed on the heels of a protracted showdown pitting BCBSM against Spectrum Health, a Grand Rapids-based hospital system. By taking a hard line with Sparrow, the health plan was trying to stem the pushback from other hospitals around the state. BCBSM’s strong stance on behalf of employers’ desire for cost control recalls an episode a few years ago when the health plan, with the backing of business, refused to contract with three newly opened ambulatory surgery centers (it later relented in the face of a court challenge by the centers). As the year-end deadline neared, Sparrow and BCBSM agreed to extend the existing contract for six months, but details of the deal were not made public.

While battling Sparrow, BCBSM faced large financial losses in the small group insurance market and a legislative initiative to alter the health plan’s structure. Under state law, BCBSM is the payer of last resort in the small group market (no longer the case in most states), the only carrier required to community rate these products with adjustments only for geographic regions and industries defined by the state. In contrast, other insurers can adjust premiums for age and sex, as well as industry, and, thus, offer younger, healthier groups rates as much as 30 percent to 40 percent lower than BCBSM’s. As less-healthy groups remain in Blue Cross and Blue Shield products, the company must increase its premiums, which encourages more groups to switch to less-expensive health plans. The result, BCBSM says, has been small group market losses totaling $400 million between 1997 and 2001.

The Blues sought legislative relief in 2002, proposing that all carriers have the same rating rules for the small group market. As part of small group reforms, then-Governor John Engler proposed greater state oversight of Blue Cross and Blue Shield and reducing its board from 35 to 13 members. The state-defined BCBSM board membership now includes representatives of most major stakeholders in Michigan, such as the automakers, unions and health care providers. Engler’s plan would have removed many of these stakeholders, thus reducing the board’s publicly representative nature. He also proposed a procedure if the health plan decided to convert from nonprofit to for-profit status. BCBSM’s stated disinterest in converting to a for-profit, along with broad opposition to the changes in board membership, sank the proposed reforms. With a new governor and legislature elected in 2002, it is unclear whether small group market legislation will be passed in the near future.

Consumers Pay More Despite Strong Economy

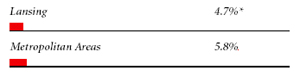

![]() ansing has been shielded somewhat from the national economic downturn,

but that has not protected residents from paying more for health insurance. The

economic stability is due in part to the presence of the area’s three major, highly

unionized employers, none of which has had to lay off workers over the past two

years. Indeed, although the unemployment rate in Lansing rose from 2.5 percent in

2000 to 4.0 percent in 2002, it was still below the 5.8 percent national average.

Nevertheless, double-digit increases in health care costs in each of the last four

years have left Lansing employers in an economic bind and, coupled with lower

business revenues, have depressed wages.

ansing has been shielded somewhat from the national economic downturn,

but that has not protected residents from paying more for health insurance. The

economic stability is due in part to the presence of the area’s three major, highly

unionized employers, none of which has had to lay off workers over the past two

years. Indeed, although the unemployment rate in Lansing rose from 2.5 percent in

2000 to 4.0 percent in 2002, it was still below the 5.8 percent national average.

Nevertheless, double-digit increases in health care costs in each of the last four

years have left Lansing employers in an economic bind and, coupled with lower

business revenues, have depressed wages.

In an attempt to rein in costs and limit their own spending increases, employers have shifted a greater portion of costs to their employees. For example, small firms in Lansing historically offered benefits that mirrored the comprehensiveness of those offered to union members in larger companies. During the past two years, however, small employers have shifted more costs to employees in the form of higher deductibles, copayments and employee premium contributions. Also, two- and three-tiered pharmacy benefits are becoming more widespread. Consumers in the individual insurance market also have been hit with cost increases; in January 2003, the state approved a 23 percent increase for BCBSM individual products, reportedly the first hike in six years.

Despite recent changes, many Lansing employees, particularly those who work for large companies, continue to have generous health benefits. Copayments and deductibles are low, and loosely managed, highly inclusive preferred provider organizations (PPOs) are prevalent and tend to be priced similarly to HMOs in the market. Because HMOs and PPOs have similarly broad networks and comprehensive benefit packages, it has been difficult for HMOs to be priced less expensively than PPOs, which in turn has made it difficult for them to attract substantial enrollment.

Lansing’s historically rich health benefits packages are due in no small part to the tough negotiating stances of powerful unions associated with all of the major employers. In the past, pressures from unions made it difficult for employers to change benefits. But since 2000, unions—at least those representing public employees—have shifted their stance on health benefits and have begun to collaborate with management’s cost-containment goals. For instance, the state of Michigan took a big step forward in managing health care costs by retiring its traditional indemnity plan and adopting a PPO, with the agreement of one of its major unions. Although this change eliminated first-dollar coverage for hospitalizations and surgeries, the unions successfully negotiated lower deductibles and added coverage of preventive services. MSU’s unions resisted a move requiring that employees share a portion of the premium but agreed to include health insurance premium increases as a factor in determining wage increases. One benefit from this agreement is that both unions and employers are now searching proactively for ways to lower health care costs.

Market, Policy Strain Provider Capacity

![]() ansing is pushing the limits of its health care system’s ability to provide certain

services. Hospital capacity constraints and shortages of such diagnostic equipment

as CAT scanners and magnetic resonance imaging devices are causing delays in care.

Twelve to 18 months ago, both Sparrow and Ingham Regional Medical Center

frequently had to divert ambulances from their emergency departments, sometimes

at the same time.

ansing is pushing the limits of its health care system’s ability to provide certain

services. Hospital capacity constraints and shortages of such diagnostic equipment

as CAT scanners and magnetic resonance imaging devices are causing delays in care.

Twelve to 18 months ago, both Sparrow and Ingham Regional Medical Center

frequently had to divert ambulances from their emergency departments, sometimes

at the same time.

The frequency of these diversions decreased over the past year as hospitals worked to improve efficiency and patient flows, but long waiting times in the emergency department continue, and some physicians believe patients are not receiving care in a timely fashion or are leaving emergency rooms inappropriately. These constraints are believed to be the result of the consolidation of four hospitals into two, an aging population, more people using hospital emergency departments for primary care, some inefficiencies in how hospitals manage patient demand, health care labor force shortages and certificate-of-need(CON) regulation.

Ingham Regional has been the primary competitor of the larger Sparrow Health System since both were formed from mergers in the mid-1990s, but their relative market shares have remained stable since then, roughly 35 percent and 65 percent, respectively. They compete on perceived quality—advertising their rankings in a variety of proprietary performance rating systems (e.g., Solucient, HealthGrades.com, U.S. News and World Report)-and on specialty facilities and other amenities. Renovated or new facilities are designed both to gain market advantage in specific service niches and to improve overall efficiency to cope with very high occupancy rates, hovering at 80 percent to 85 percent in late 2002.

For example, Sparrow is adding a new floor with as many as 35 surgery rooms, in part to accommodate increased cardiology volume, and a new parking deck to make it easier for patients and employees to get in and out of the hospital. Ingham Regional is adding 33 orthopedic beds and recruiting a neurosurgery group to compete with Sparrow for these patients and is planning a new cardiac care tower. Both systems are also considering starting long-term acute care hospitals that would alleviate pressure on existing acute care beds.

Unlike the hospital market, Lansing’s physician market is relatively fragmented, composed mostly of groups with fewer than 10 members (although three larger groups have formed gradually over the last four or five years). But like the hospital sector, a shortage of specialists in fields such as otolaryngology, orthopedics, neurosurgery and infectious diseases has impeded access for patients. Moreover, physician shortages and limited evening office hours may be contributing to greater hospital emergency room use, thus exacerbating capacity problems. Some observers fear these shortages might worsen, because many of the specialists in Lansing are 50 or older and there are few younger physicians to replace them.

Two other factors may play a role in capacity and access constraints. First, Lansing has two nursing schools, but many of their graduates leave the area. As a result, hospitals are not always able to staff all shifts. Second,Michigan still has relatively stringent CON regulations that require health care organizations to obtain state approval to add new beds, major new services or very expensive equipment. Although stakeholders disagree about CON’s effectiveness, hospitals and large employers in Michigan strongly support it, while physicians view it as a significant barrier to expanding capacity, especially for ambulatory facilities.

Access Improves for Low-Income Residents Despite Budget Woes

![]() ven as Lansing struggles with rising costs and provider

capacity constraints, access to health services, especially primary care, for

low-income patients has improved since 2000. The main reason for this progress

is the Ingham Health Plan (IHP), a four-year-old local model that combines local,

state and federal funds to pay directly for primary care and prescriptions for

uninsured residents. Managed by the Ingham County Health Department, the plan

now serves more than 16,000 people, about 60 percent of the county’s uninsured

population, representing a 45 percent increase since 2000. IHP members can obtain

primary care from one of 31 sites, including health department clinics, freestanding

community health centers and some private physician offices. Low-income patients

can also obtain prescriptions through a separate IHP pharmaceutical assistance

program.

ven as Lansing struggles with rising costs and provider

capacity constraints, access to health services, especially primary care, for

low-income patients has improved since 2000. The main reason for this progress

is the Ingham Health Plan (IHP), a four-year-old local model that combines local,

state and federal funds to pay directly for primary care and prescriptions for

uninsured residents. Managed by the Ingham County Health Department, the plan

now serves more than 16,000 people, about 60 percent of the county’s uninsured

population, representing a 45 percent increase since 2000. IHP members can obtain

primary care from one of 31 sites, including health department clinics, freestanding

community health centers and some private physician offices. Low-income patients

can also obtain prescriptions through a separate IHP pharmaceutical assistance

program.

Coverage for specialty care is quite limited, however. A pool of about $500,000 pays for some inpatient care at Lansing’s two hospitals, but expenses beyond this limit are not reimbursed. Despite this limitation, the Ingham Health Plan’s success is applauded widely and has been replicated in about 12 other Michigan counties, with programs serving another 25 counties in the works. In addition, leaders of local safety net institutions and state and local policy makers expect that IHP funding will remain secure in the near term despite the state’s budget woes.

The Ingham Health Plan was also an important factor in the overall financial stability of Lansing’s community health centers. Cristo Rey Center, based in the city’s Hispanic community, serves 2,000 IHP patients, up from 800 two years ago. This added patient care revenue—along with more aggressive copayment collections and fund-raising efforts—allowed the clinic to build a new wing. Revenues at the local health department’s primary care clinics are also up, even though they had to give up about $2 million that was used to start up the IHP. To earn back that lost funding, the clinics needed to serve—and get paid for—about 8,000 IHP patients. In fact, they now serve 11,000 such patients, giving them a net increase in revenue.

Expansions of Michigan’s Medicaid and MIChild, the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP), also helped the safety net in Lansing, but these gains are threatened by the state’s current budget problems. Between 2000 and 2002, 200,000 more people statewide were insured through Medicaid and MIChild, partly due to aggressive outreach initiatives and simplified application procedures. These efforts largely came to a halt in 2002, as Governor Engler sought to balance the state budget in his last year in office. Engler instituted $337 million in budget cuts, including $34.5 million for the Medicaid managed care program, and withdrew a federal waiver application that would have added about 170,000 adults to Medicaid.

Despite these economies, Michigan’s new governor, Jennifer Granholm, still faced a $1.7 billion budget shortfall for fiscal year 2004. One of her primary cost-cutting tools—Michigan’s Medicaid preferred drug list—is being challenged in court by the pharmaceutical industry. The formulary, which reportedly saves the state $850,000 each week, was upheld by a U.S. District Court, but further challenges are likely.With virtually all Medicaid-eligible women and children in prepaid health plans,Michigan will face considerable pressure from plans to maintain adequate payments. Indeed, the budget Granholm proposed in March 2003 largely protects Medicaid provider payment rates, eligibility and benefits (except for adults), in part by increasing the proportion of tobacco settlement funds going to health care. Still, concerns remain about the effects of final budget decisions on public health care programs.

Issues to Track

![]() ansing residents have faced a flurry of new access problems

over the past two years. The contract dispute between BCBSM and Sparrow Health

System threatened continuity of care for up to 67,000 people. Strained hospital

and physician services have raised questions about Lansing residents’ access

to timely and appropriate medical care. Meanwhile, fast-rising insurance premiums

and growing willingness to shift costs to consumers are making health insurance

less affordable, even as potentially deep state budget cuts threaten to limit

access to public insurance coverage.

ansing residents have faced a flurry of new access problems

over the past two years. The contract dispute between BCBSM and Sparrow Health

System threatened continuity of care for up to 67,000 people. Strained hospital

and physician services have raised questions about Lansing residents’ access

to timely and appropriate medical care. Meanwhile, fast-rising insurance premiums

and growing willingness to shift costs to consumers are making health insurance

less affordable, even as potentially deep state budget cuts threaten to limit

access to public insurance coverage.

Issues to track are:

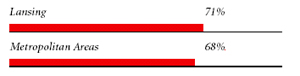

Lansing Consumers’ Access to Care, 2001

Lansing compared to metropolitan areas with over 200.000 population

| Unmet Need |

| PERSONS WHO DID NOT GET NEEDED MEDICAL CARE DURING THE LAST 12 MONTHS |

|

| Delayed Care |

| PERSONS WHO DELAYED GETTING NEEDED MEDICAL CARE DURING THE LAST 12 MONTHS |

|

| Out-of-Pocket Costs |

| PRIVATELY INSURED PEOPLE IN FAMILIES WITH ANNUAL OUT-OF-POCKET COSTS OF $500 OR MORE |

|

| Access to Physicians |

| PHYSICIANS WILLING TO ACCEPT ALL NEW PATIENTS WITH PRIVATE INSURANCE |

|

| PHYSICIANS WILLING TO ACCEPT ALL NEW MEDICARE PATIENTS |

|

| PHYSICIANS WILLING TO ACCEPT ALL NEW MEDICAID PATIENTS |

|

| PHYSICIANS PROVIDING CHARITY CARE |

|

| * Site value is significantly different from the mean for large metropolitan

areas over 200,000 population at p<.05. † Indicates a 12-site low. Source: HSC Community Tracking Study Household and Physician Surveys, 2000-01 Note: If a person reported both an unmet need and delayed care, that person is counted as having an unmet need only. Based on follow-up questions asking for reasons for unmet needs or delayed care, data include only responses where at least one of the reasons was related to the health care system. Responses related only to personal reasons were not considered as unmet need or delayed care. |

Background and Observations

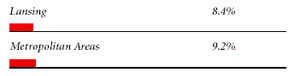

| Lansing Demographics | |

| Lansing | Metropolitan areas 200,000+ population |

| Population1 449,118 |

|

| Persons Age 65 or Older2 | |

| 10% | 11% |

| Median Family Income2 | |

| $34,986 | $31,883 |

| Unemployment Rate3 | |

| 4.0% | 5.8%* |

| Persons Living in Poverty2 | |

| 8.5% | 12% |

| Persons Without Health Insurance2 | |

| 7.0% | 13% |

| Age-Adjusted Mortality Rate per 1,000 Population4 | |

| 8.4 | 8.8* |

* National average. Sources: |

|

| Health Care Utilization | |

| Lansing | Metropolitan areas 200,000 population |

| Adjusted Inpatient Admissions per 1,000 Population 1 | |

| 186 | 180 |

| Persons with Any Emergency Room Visit in Past Year 2 | |

| 20% | 19% |

| Persons with Any Doctor Visit in Past Year 2 | |

| 81% | 78% |

| Average Number of Surgeries in Past Year per 100 Persons 2 | |

| 22 | 17 |

| Sources: 1. American Hospital Association, 2000 2. HSC Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 2000-01 |

|

| Health System Characteristics | |

| Lansing | Metropolitan areas 200,000+ population |

| Staffed Hospital Beds per 1,000 Population1 | |

| 2.1 | 2.5 |

| Physicians per 1,000 Population2 | |

| 1.2 | 1.9 |

| HMO Penetration, 19993 | |

| 41% | 38% |

| HMO Penetration, 20014 | |

| 37% | 37% |

| Medicare-Adjusted Average per Capita Cost (AAPCC) Rate, 20025 | |

| $553 | $575 |

| Sources: 1. American Hospital Association, 2000 2. Area Resource File, 2002 (includes nonfederal, patient care physicians, except radiologists, pathologists and anesthesiologists) 3. InterStudy Competitive Edge, 10.1 4. InterStudy Competitive Edge, 11.2 5. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Site estimate is payment rate for largest county in site; national estimate is national per capita spending on Medicare enrollees in Coordinated Care Plans in December 2002. |

|