Community Report No. 6

Spring 2003

Suzanne Felt-Lisk, Jon B. Christianson, Linda R. Brewster, Ashley C. Short, Richard Sorian, Robert E. Hurley, Lawrence D. Brown, Jessica H. May

The end of long-standing exclusive contracts between the dominant Greenville Hospital System (GHS) and two major health plans, coupled with increased hospital expansion, suggests health care costs will continue to rise in Greenville. With the demise of the exclusive contracts, the health plans will no longer reap deep price discounts from GHS in return for excluding rival Bon Secours St. Francis Hospital from the insurers’ provider networks. At the same time, hospital construction projects have increased, as hospitals compete in previously uncontested geographic areas with significant population growth.

In other developments:

- Hospital Ends Exclusive Contracts, Competition Intensifies

- BlueCross Solidifies Position, but Contract Tensions Increase

- Employers Are Shifting More Costs to Consumers

- Medicaid Stability Tied to Tobacco Tax Proposal

- Greater Demand for Services from Safety Net Providers

- Issues to Track

- Greenville Consumers’ Access to Care, 2001

- Background and Observations

Hospital Ends Exclusive Contracts, Competition Intensifies

![]() he ongoing intense competition between GHS and St. Francis

Hospital took two turns recently that some fear will increase costs. After a

lawsuit brought the issue to the forefront, St. Francis achieved a long sought

goal of inclusion in the provider networks of BlueCross BlueShield of South

Carolina in 2001 and CIGNA in 2003, after the health plans ended exclusive contracts

with GHS. Consumers now have equal access to both hospital systems, but plans’

ability to hold down costs may have been weakened.

he ongoing intense competition between GHS and St. Francis

Hospital took two turns recently that some fear will increase costs. After a

lawsuit brought the issue to the forefront, St. Francis achieved a long sought

goal of inclusion in the provider networks of BlueCross BlueShield of South

Carolina in 2001 and CIGNA in 2003, after the health plans ended exclusive contracts

with GHS. Consumers now have equal access to both hospital systems, but plans’

ability to hold down costs may have been weakened.

In the past, the two plans had excluded St. Francis in exchange for substantial discounts from GHS. But in 2001, as a health plan executive noted, "all the stars were aligned" for this arrangement to end. Population growth and rising utilization, along with the exclusive contracts, pushed demand for GHS services beyond the hospital’s capacity. At the same time, St. Francis stopped a long-standing practice of waiving coinsurance requirements for out-of-network patients, putting additional pressure on GHS’ capacity and on consumers by increasing their out-of-pocket costs.

In early 2001, St. Francis reported difficulty in getting BlueCross to pay out-of-network claims and sued the plan. Meanwhile, GHS agreed to relinquish exclusivity in exchange for higher payment rates. St. Francis and BlueCross settled the suit, and the plan soon agreed to add St. Francis to its provider network. However, St. Francis had to agree to some discount to gain the new contract. St. Francis hopes the new arrangement will improve its market position in the longer term, but to date neither profitability nor patient volume has improved as much as the hospital had hoped. Responding to market pressures, CIGNA added St. Francis to its network in January 2003. The end of exclusive contracting may contribute to overall cost increases since both health plans lost deeply discounted prices from GHS.

The second development raising cost concerns is the spike in hospital construction projects and expansion plans. For example, both GHS and St. Francis are vying to win state certificate-of-need (CON) approval to add inpatient capacity on the growing east side of Greenville. GHS plans to build a 110-bed hospital across the street from where St. Francis hopes to add beds. Because the state has ruled that the two CON applications are noncompeting, both could be approved in a process viewed by some as driven more by politics than needs-based analysis. In nearby Greer, GHS plans to build another 110-bed hospital, replacing a smaller facility and expanding in an area where another hospital system, Spartanburg Regional Healthcare System, has just purchased a large tract of land for an as-yet unspecified purpose.

Greenville-area hospitals are competing not just for patient loyalty in previously uncontested geographic areas but also for lucrative specialty services. Hospitals hope that developing stronger reputations in certain specialty areas will draw patients and enhance their market positions. Patients now have five different hospital options for cardiac surgery within a 50-mile radius of downtown Greenville, two of which reportedly treated fewer open heart surgery patients last year than nationally recommended volume standards. Maintaining such low-volume, high-tech services may increase costs and raises questions about quality of care.

Hospital competition for specialty services is shaped in part by the trend toward specialists adding capacity to perform more procedures in their offices. Some physician groups have purchased used equipment or leased mobile services to avoid filing for a CON that hospitals might contest. As a result, hospitals now are willing to consider partnering with physicians. GHS formed a partnership with the market’s largest oncology group to develop a regional cancer center program to strengthen what the hospital system views as a strategically important service. Likewise, Spartanburg Regional Healthcare System collaborated with local surgeons to open a joint venture, multi-specilty ambulatory surgery center in 2002.

BlueCross Solidifies Position, but Contract Tensions Increase

![]() lueCross’ stature as the market’s leading plan solidified

as the major competing plans—Carolina Care Plan and CIGNA—struggled

with organizational and financial challenges. Carolina Care Plan, formerly Physicians

Health Plan, has encountered transition challenges since breaking off a long-term

management agreement with United Healthcare, prompting it to overhaul its operating

systems. CIGNA had a sizable operating loss in 2001 in South Carolina.

lueCross’ stature as the market’s leading plan solidified

as the major competing plans—Carolina Care Plan and CIGNA—struggled

with organizational and financial challenges. Carolina Care Plan, formerly Physicians

Health Plan, has encountered transition challenges since breaking off a long-term

management agreement with United Healthcare, prompting it to overhaul its operating

systems. CIGNA had a sizable operating loss in 2001 in South Carolina.

Both plans have focused on improving profitability rather than growing or maintaining market share. Meanwhile, BlueCross’ market share increased as the plan won accounts formerly served by other plans and expanded the range of managed care products it offers in the market. The new products include a health maintenance organization (HMO) with open access to specialists (no referrals needed), a consumer-driven health plan and a plan for small businesses where patients pay 30 percent of each claim. Other plans have introduced open-access products, and BlueCross discontinued one of two HMO products, marking the further decline of HMO-style managed care, which was never well accepted in Greenville.

Despite its influence, BlueCross, along with other plans, has faced increasingly tense contract negotiations with some providers, particularly hospitals and certain specialty groups. Some groups threatened to terminate health plan contracts if their demands for higher payment rates were not taken seriously.With consumers demanding a broad choice of providers, and heavy consolidation in some specialties, providers have gained the bargaining advantage. As a result, providers generally appear to have succeeded in extracting rate increases from the plans, contributing to higher overall health care costs.

Health plans in Greenville, as in other markets, are more inclined to accommodate the demands of providers and consumers than act forcefully to limit health care cost increases. In modest efforts at cost control, plans are developing tiered-network products, which could sensitize consumers to price differences across providers and pressure providers to lower prices to be placed in a favorable tier. However, it is not clear yet whether area hospitals will accept such designs, whether the plans will have the power to impose them or whether employers are interested enough to make such products viable. The future for consumer-driven products featuring fixed employer contributions and personal spending accounts also is uncertain, with only cautious interest among a few employers.

Some plans are trying to strengthen disease management programs to help control costs, but their cost-control potential is not yet widely proved. Plans generally are passing on increased costs to purchasers and offering options with higher patient cost sharing and reduced benefits to help lower premium increases. A third party administrator firm, for example, reported more purchasers are interested in preferred provider organizations (PPOs) with greater cost sharing. Instead of offering a PPO with no coinsurance for in-network expenses and 10 percent for out-of-network expenses, some firms now require workers to pay 20 percent coinsurance for in-network care and 40 percent for out-of-network expenses.

Employers Are Shifting More Costs to Consumers

![]() ising health care costs and a faltering economy have frustrated

area employers, who believe they have few ways to control costs and little leverage

with plans or providers. Although local estimates varied, employee benefit consultants

and brokers suggested large employers’ premiums have increased 9 percent to

15 percent a year for the past three years, while small employers saw even higher

increases—15 percent to 20 percent or higher for each of the past two

years. Employers and others expect the rapid rise in costs to continue.

ising health care costs and a faltering economy have frustrated

area employers, who believe they have few ways to control costs and little leverage

with plans or providers. Although local estimates varied, employee benefit consultants

and brokers suggested large employers’ premiums have increased 9 percent to

15 percent a year for the past three years, while small employers saw even higher

increases—15 percent to 20 percent or higher for each of the past two

years. Employers and others expect the rapid rise in costs to continue.

Although the Greenville-area economy is softer than two years ago, observers noted the local economy remains stronger than other parts of South Carolina. The Greenville market is noted for the large national and multinational companies that moved into the area over the past decade, attracted by low wage rates. These companies include Michelin, BMW, Hitachi, GE and KEMET Electronics.

The textile industry is in long-term decline, with several companies with plants in the area currently operating under bankruptcy protection. In addition, GE and KEMET Electronics have reduced their local presence through downsizing. But unemployment has been cushioned by the continued job growth at BMW, which expected to gain between 4,000 and 10,000 workers in the next few years.

Greenville has a number of small manufacturing firms that largely serve BMW, Michelin and the other large employers. These small suppliers, however, are facing significant competition, particularly from foreign companies. Moreover, these small employers, while suppliers for the large firms, often compete with the large firms for the same workers but are less able to afford comparable benefits, including health insurance.

The limited role of labor unions in South Carolina has left employers less constrained to change health benefits than employers in markets with heavily unionized workforces. Many Greenville employers have increased consumer cost sharing in one or more of the following ways: increasing the share of employee premium contributions for single and family coverage, increasing PPO deductibles and increasing coinsurance rates or copayments. Some employers also are introducing separate deductibles for services perceived as overused. For example, many employers reportedly are instituting a separate deductible for using emergency rooms for nonemergency care.

To cope with continuing cost increases, employers are planning to shift even more costs to consumers but are not abandoning coverage. Large employers continue to offer coverage, and there were no widespread reports of small employers dropping health insurance.

The large, self-insured state employee health plan has had lower premium increases for the past three years than private sector employers. Despite the state plan’s favorable experience, it faces a large projected premium increase this year—as high as 24 percent—and may have to institute substantial benefit changes for 2004. The state has devoted considerable effort to educate workers about the need for benefit changes. The state plan’s projected cost increases coincide with a large state budget deficit that constrains the state’s ability to pay.

Medicaid Stability Tied to Tobacco Tax Proposal

![]() outh Carolina’s budget deficit, projected at $348 million in fiscal year 2003, has

raised concerns among stakeholders who fear substantial Medicaid and SCHIP

reductions in the coming year, unless a second year of major stopgap funding can

be found or a hotly debated tobacco tax proposal is passed. Medicaid and SCHIP

serve 23 percent of the state’s population and pay for half the births in the state.

Last year, substantial cuts were avoided only after a fierce legislative battle, which

ended when tobacco settlement money and cuts in other government programs

were used on a one-time basis to cover spending increases sparked by higher

Medicaid and SCHIP enrollment in recent years.

outh Carolina’s budget deficit, projected at $348 million in fiscal year 2003, has

raised concerns among stakeholders who fear substantial Medicaid and SCHIP

reductions in the coming year, unless a second year of major stopgap funding can

be found or a hotly debated tobacco tax proposal is passed. Medicaid and SCHIP

serve 23 percent of the state’s population and pay for half the births in the state.

Last year, substantial cuts were avoided only after a fierce legislative battle, which

ended when tobacco settlement money and cuts in other government programs

were used on a one-time basis to cover spending increases sparked by higher

Medicaid and SCHIP enrollment in recent years.

To date, the state Medicaid agency has focused on controlling costs without major changes to eligibility rules, although some policy changes have tightened Medicaid and SCHIP enrollment and eligibility. For example, child support payments are no longer excluded when determining income eligibility. The agency also changed payment policy for many people dually enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid, substantially reducing payment for Medicare beneficiaries’ deductibles and coinsurance. The resulting declines in payment to physicians have reduced the number of physicians willing to accept these patients. Using a Medicaid waiver to draw federal funding without increasing state outlays, the state has expanded a pharmaceutical discount program for low-income seniors.

To avoid more serious Medicaid and SCHIP eligibility and benefit cuts in fiscal year 2004, many stakeholders believed the best hope was passage of a substantial tobacco tax increase. South Carolina has one of the lowest tobacco taxes in the country, and health care interests, including consumer advocates, the state hospital and medical associations and many providers, have lobbied to increase the tobacco tax and earmark the proceeds for Medicaid and SCHIP.

Greater Demand for Services from Safety Net Providers

![]() ince 1997, strong community cooperation, coupled with grants and other funding,

has strengthened Greenville’s safety net. In the past two years, parts of the safety

net have continued to expand and improve, while new challenges have arisen in the

downtown Greenville area.

ince 1997, strong community cooperation, coupled with grants and other funding,

has strengthened Greenville’s safety net. In the past two years, parts of the safety

net have continued to expand and improve, while new challenges have arisen in the

downtown Greenville area.

The area’s steady population growth, along with the economic downturn, has increased the number of uninsured patients seeking care at the Greenville Free Medical Clinic and New Horizon Family Health Services, the area’s sole community health center (CHC). Last year, the Free Clinic served 1,800 new uninsured patients—mostly laid-off workers. Although children’s enrollment in Medicaid and SCHIP has climbed steadily since 1997, new enrollees reportedly have trouble finding private physicians who will accept them as patients, so they continue to seek primary care at the same safety net facilities as the uninsured.

While demand for safety net services has increased, outpatient capacity in the downtown area has declined because GHS, a major safety net provider, closed some clinics. In addition, GHS has reduced services at some of the remaining clinics as it restructures them to focus on their teaching mission. Private physicians in Greenville reportedly have always been reluctant to accept low-income patients, including Medicaid beneficiaries, and primary care physicians are in short or barely adequate supply, even for privately insured patients.

The combined effect of more uninsured people and reduced capacity has worsened access to care in the downtown area. Despite recruiting some new volunteer doctors, the Free Clinic had to turn people away for the first time in 2002. Every day, two hours before the doctors arrive, sick people are lined up outside the clinic to ensure they can sign in early and be seen that day. And the waiting time for a new patient appointment at New Horizon’s main site has increased to about eight weeks.

Meanwhile, in areas outside downtown Greenville, access appears to have improved. Greenville’s Community Health Alliance (CHA), run by the United Way, has been a catalyst in these improvements. Formed in 1998, CHA brings physicians, hospital systems, nonhospital safety net providers, the local health department and advocates to the table to address the needs of Greenville County’s uninsured.

The alliance helped the community’s two major primary care safety net providers secure additional funding to expand services in the outer reaches of Greenville County. A federal CHC expansion grant helped New Horizon Family Health Services increase services, particularly in outlying areas, while the Greenville Free Medical Clinic obtained a Duke Endowment grant and other funding for start-up of new sires. The Free Clinic alone provided about 2,000 medical visits in 2002 to uninsured people in the new satellite locations. While service reductions at GHS’ downtown clinics have added to demands on other safety net providers, the system has participated in and contributed financially to the CHA and expanded services in other county areas.

Issues to Track

![]() t the same time Greenville hospitals are

expanding capacity and increasing competition for lucrative specialty services,

employers are facing another year of double-digit health insurance premium

increases. With economic conditions remaining gloomy at worst to uncertain

at best, more people are at risk of losing health coverage, and safety net providers

are already facing overload in some areas.

t the same time Greenville hospitals are

expanding capacity and increasing competition for lucrative specialty services,

employers are facing another year of double-digit health insurance premium

increases. With economic conditions remaining gloomy at worst to uncertain

at best, more people are at risk of losing health coverage, and safety net providers

are already facing overload in some areas.

Key issues to track in the Greenville market include:

Greenville Consumers’ Access to Care, 2001

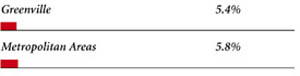

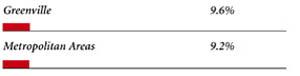

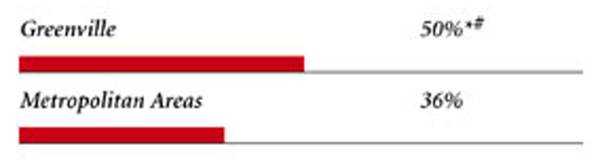

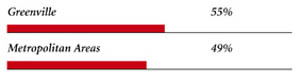

Greenville compared to metropolitan areas with over 200.000 population

| Unmet Need |

| PERSONS WHO DID NOT GET NEEDED MEDICAL CARE DURING THE LAST 12 MONTHS |

|

| Delayed Care |

| PERSONS WHO DELAYED GETTING NEEDED MEDICAL CARE DURING THE LAST 12 MONTHS |

|

| Out-of-Pocket Costs |

| PRIVATELY INSURED PEOPLE IN FAMILIES WITH OUT-OF-POCKET COSTS OF $500 OR MORE |

|

| Access to Physicians |

| PHYSICIANS WILLING TO ACCEPT ALL NEW PATIENTS WITH PRIVATE INSURANCE |

|

| PHYSICIANS WILLING TO ACCEPT ALL NEW MEDICARE PATIENTS |

|

| PHYSICIANS WILLING TO ACCEPT ALL NEW MEDICAID PATIENTS |

|

| PHYSICIANS PROVIDING CHARITY CARE |

|

| * Site value is significantly different from the mean for large metropolitan

areas over 200,000 population at p<.05. † Indicates a 12-site low. Source: HSC Community Tracking Study Household and Physician Surveys, 2000-01 Note: If a person reported both an unmet need and delayed care, that person is counted as having an unmet need only. Based on follow-up questions asking for reasons for unmet needs or delayed care, data include only responses where at least one of the reasons was related to the health care system. Responses related only to personal reasons were not considered as unmet need or delayed care. |

Background and Observations

| Greenville Demographics | |

| Greenville | Metropolitan areas 200,000+ population |

| Population1 978,213 |

|

| Persons Age 65 or Older2 | |

| 12% | 11% |

| Median Family Income2 | |

| $29,683 | $31,883 |

| Unemployment Rate3 | |

| 5.8% | 5.8% |

| Persons Living in Poverty2 | |

| 13% | 12% |

| Persons Without Health Insurance2 | |

| 12% | 13% |

| Age-Adjusted Mortality Rate per 1,000 Population4 | |

| 9.8 | 8.8* |

* National average. Sources: |

|

| Health Care Utilization | |

| Greenville | Metropolitan areas 200,000 population |

| Adjusted Inpatient Admissions per 1,000 Population 1 | |

| 190 | 180 |

| Persons with Any Emergency Room Visit in Past Year 2 | |

| 19% | 19% |

| Persons with Any Doctor Visit in Past Year 2 | |

| 79% | 78% |

| Average Number of Surgeries in Past Year per 100 Persons 2 | |

| 18 | 17 |

| Sources: 1. American Hospital Association, 2000 2. HSC Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 2000-01 |

|

| Health System Characteristics | |

| Greenville | Metropolitan areas 200,000+ population |

| Staffed Hospital Beds per 1,000 Population1 | |

| 2.5 | 2.5 |

| Physicians per 1,000 Population2 | |

| 1.6 | 1.9 |

| HMO Penetration, 19993 | |

| 13% | 38% |

| HMO Penetration, 20014 | |

| 11% | 37% |

| Medicare-Adjusted Average per Capita Cost (AAPCC) Rate, 20025 | |

| $553 | $575 |

| Sources: 1. American Hospital Association, 2000 2. Area Resource File, 2002 (includes nonfederal, patient care physicians, except radiologists, pathologists and anesthesiologists) 3. InterStudy Competitive Edge, 10.1 4. InterStudy Competitive Edge, 11.2 5. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Site estimate is payment rate for largest county in site; national estimate is national per capita spending on Medicare enrollees in Coordinated Care Plans in December 2002. |

|