Community Report No. 8

Summer 2003

Debra A. Draper, John F. Hoadley, Jessica Mittler, Sylvia Kuo, Gloria J. Bazzoli, Peter J. Cunningham, Len M. Nichols, Leslie Jackson Conwell

With health insurance premiums continuing to increase, Little Rock residents and employers are growing more frustrated, viewing their situation as untenable. In response, area employers have increased workers’ share of premiums and raised deductibles and copayments. But local incomes are not keeping pace with these higher costs, pricing health insurance out of reach for many workers and their families. Some employees are dropping their employer-based coverage and, if young and healthy enough, finding lower-priced coverage in the individual market. Others are enrolling their children in public insurance programs when they can meet the state’s eligibility requirements.

Other notable developments are:

- Escalating Health Care Costs Burden Low-Wage Workers

- Limited Health Plan Competition Frustrates Employers

- Competition Threatens Hospital Profitability

- Medicaid Covers More Kids, but Eligibility Tight for Adults

- Improved Finances, New Capacity Strengthen Safety Net

- Issues to Track

- Little Rock Consumers’ Access to Care, 2001

- Background and Observations

Escalating Health Care Costs Burden Low-Wage Workers

![]() apidly rising health insurance premiums are prompting

Little Rock employers to shift more health care costs to their workers. Not

only have employers increased deductibles and copayments—continuing a

trend from two years ago—but they also have passed on a higher share of

the premium to employees, which, in 2002, grew roughly 10 percent to 15 percent

for large employers and 10 percent to 25 percent and sometimes higher for small

employers. Employers’ overriding goal is to pass along enough costs to mitigate,

as much as possible, the financial impact of rising premiums. Compared to other

markets, however, Little Rock’s lower median family income and higher percentage

of the population living in poverty leaves employees hard-pressed to afford

the increased financial burden.

apidly rising health insurance premiums are prompting

Little Rock employers to shift more health care costs to their workers. Not

only have employers increased deductibles and copayments—continuing a

trend from two years ago—but they also have passed on a higher share of

the premium to employees, which, in 2002, grew roughly 10 percent to 15 percent

for large employers and 10 percent to 25 percent and sometimes higher for small

employers. Employers’ overriding goal is to pass along enough costs to mitigate,

as much as possible, the financial impact of rising premiums. Compared to other

markets, however, Little Rock’s lower median family income and higher percentage

of the population living in poverty leaves employees hard-pressed to afford

the increased financial burden.

There are few large employers in Little Rock, and those that do exist often have only a small concentration of local employees and are unable to influence health care costs significantly. In addition, the absence of labor unions (Arkansas is a right-to-work state) leaves employers comparatively less constrained in passing costs on to their workforce. Observers note that small employers, in particular, are having difficulty maintaining health benefits due to rising costs, and a few have dropped coverage altogether. Some fear more coverage cutbacks if premiums continue to escalate.

Local observers report some employees have opted out of their employer’s plan to seek coverage in the individual market, where, if they are young and healthy enough, they can find coverage priced lower than the contribution required by their employer’s plan. Arkansas Blue Cross Blue Shield (ABCBS), particularly active in the individual insurance market, has developed specific products targeting these consumers. The situation will become problematic, however, if those employees left in the employer-based plan are older and in poorer health, since they use health care services more frequently. There are also reports of parents opting for single coverage under their employers’ plans and seeking coverage for their children in the individual insurance market or, if they meet eligibility requirements, in the state’s public insurance programs.

Limited Health Plan Competition Frustrates Employers

![]() mployers are frustrated by the limited health plan competition

in Little Rock, blaming it in part for the double-digit premium increases of

the past two years. Plans argue that premium hikes are the result of providers’

demands for higher payments, increased service utilization, new technologies

and rising pharmaceutical costs and use. While employers and their workers are

paying more, however, health plans are earning higher profits. Plans in the

market generally reported improved profits last year, including QualChoice QCA

Health Plan, which was on the verge of insolvency two years ago.

mployers are frustrated by the limited health plan competition

in Little Rock, blaming it in part for the double-digit premium increases of

the past two years. Plans argue that premium hikes are the result of providers’

demands for higher payments, increased service utilization, new technologies

and rising pharmaceutical costs and use. While employers and their workers are

paying more, however, health plans are earning higher profits. Plans in the

market generally reported improved profits last year, including QualChoice QCA

Health Plan, which was on the verge of insolvency two years ago.

Local observers are concerned that insurers continue to leave the market, further diminishing the health plan competition that does exist. The Arkansas Department of Insurance reports more than 60 health insurance companies have left the state in the last five years, although many of these companies appear to be small with relatively narrow market niches such as Medigap. Large national firms are also pulling back from the market. Aetna and CIGNA essentially exited the Little Rock market during the past three years, remaining only to serve national account customers.

The limited health plan competition that exists in Little Rock is due primarily to long-standing and, for the most part, exclusive plan-hospital alliances, which have resulted in a divided local health care system. On one side is the relationship between ABCBS and Baptist Health System, the two giants in the market, that was created nearly 10 years ago when the two entered into a 50/50 joint venture with the area’s largest health maintenance organization (HMO), Health Advantage. The exclusive relationship between ABCBS and Baptist extends to all of ABCBS’s products, except indemnity and preferred provider organization (PPO) plans for two large accounts, the State of Arkansas and public school employees. Another exception is that Baptist provides PPO access for a few selected payers. On the other side is the comparatively weaker alliance of QualChoice, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) and St. Vincent Health System. United HealthCare’s network includes the two hospitals in this second alliance. ABCBS, United HealthCare and QualChoice have more than 40 percent, 30 percent and 20 percent, respectively, of the HMO market share in Little Rock. Statewide, however, ABCBS accounts for approximately half of the overall health insurance market.

Plan and employer respondents noted additional factors that discourage more active health plan competition in Little Rock. First, Little Rock’s relatively small population may not support extensive competition. In similar small markets, plans’ competitive viability may be enhanced if they increase membership by expanding their services statewide, but Arkansas’ rural geography and its relatively small population do not support such a strategy. Second, local observers say that the poor health and low socioeconomic status of Arkansas’ population dampens plans’ interest in the market.

Although local observers report that ABCBS’s exclusive arrangements with hospitals throughout the state have helped to limit health plan competition, these relationships may not be as ironclad as was once thought. For example, the exclusive relationship between ABCBS and its hospital provider in Fort Smith ended in January 2003 when ABCBS also contracted with the competing hospital in the market. While this change does not affect the Little Rock market, it may suggest a willingness on the part of ABCBS to consider alternative provider contracting arrangements.

Competition Threatens Hospital Profitability

![]() lthough currently profitable, hospitals in Little Rock continue to be concerned with

competition that threatens to reduce revenues. The shift of tertiary services to

hospitals in nearby communities, begun several years ago, continues, posing a

particular challenge to Baptist, which historically has drawn patients from these

outlying communities. St. Vincent, which tends to draw most of its patients from

the local market area, has been less affected. While growth in the number of ambulatory

surgery centers (ASCs) in Little Rock has leveled off in the past two years, Baptist

and St. Vincent continue to be open to discussion about joint ventures with

physicians in the hopes of maintaining some financial share in the ambulatory

surgery business. Yet, hospital service volume is threatened further by the addition

of ancillary service capacity to physicians’ office-based practices.

lthough currently profitable, hospitals in Little Rock continue to be concerned with

competition that threatens to reduce revenues. The shift of tertiary services to

hospitals in nearby communities, begun several years ago, continues, posing a

particular challenge to Baptist, which historically has drawn patients from these

outlying communities. St. Vincent, which tends to draw most of its patients from

the local market area, has been less affected. While growth in the number of ambulatory

surgery centers (ASCs) in Little Rock has leveled off in the past two years, Baptist

and St. Vincent continue to be open to discussion about joint ventures with

physicians in the hopes of maintaining some financial share in the ambulatory

surgery business. Yet, hospital service volume is threatened further by the addition

of ancillary service capacity to physicians’ office-based practices.

Baptist currently has three joint venture ASCs, two of which have been operational since 2000; a third was opened in 2002 as a joint venture with OrthoArkansas, one of three large orthopedic groups in Little Rock. Due to OrthoArkansas’ involvement in talks about developing a freestanding specialty orthopedic hospital, Baptist proposed a 50/50 joint venture arrangement with the group. In light of the joint venture arrangement, it is unclear whether development of the hospital will continue. The only other specialty hospital in the market, Arkansas Heart Hospital, has faced numerous challenges since its 1997 opening. For example, plans exclude the hospital from their networks because it competes with their hospital partners. St. Vincent is also involved in a number of long-standing joint venture arrangements with physicians.

Medicaid Covers More Kids, but Eligibility Tight for Adults

![]() nlike many other states, Arkansas has used all of its tobacco settlement money

for health improvement projects. A state referendum passed in November 2000

expanded Medicaid coverage by using a portion of the state’s tobacco settlement

money. As a result, eligibility for pregnant women was expanded in 2002 to 200 percent

of the federal poverty level, up from 133 percent. Additionally, tobacco settlement

money was used to raise Medicaid’s cap on inpatient hospital days for adults

from 20 to 24 per year. It also has been used to fund smoking cessation and other

health promotion activities and to create a new College of Public Health at UAMS,

which began enrolling students in 2001.

nlike many other states, Arkansas has used all of its tobacco settlement money

for health improvement projects. A state referendum passed in November 2000

expanded Medicaid coverage by using a portion of the state’s tobacco settlement

money. As a result, eligibility for pregnant women was expanded in 2002 to 200 percent

of the federal poverty level, up from 133 percent. Additionally, tobacco settlement

money was used to raise Medicaid’s cap on inpatient hospital days for adults

from 20 to 24 per year. It also has been used to fund smoking cessation and other

health promotion activities and to create a new College of Public Health at UAMS,

which began enrolling students in 2001.

Despite recent program enhancements, the state’s Medicaid program, which serves approximately 150,000 adults, continues to be among the most restrictive in the nation in terms of eligibility requirements and benefits. Eligibility for those who spend down, for example, is limited to incomes below 22 percent of the federal poverty level. Additional eligibility criteria include a disability determination of six months or more and household assets of no more than $2,000.

In contrast to the limited Medicaid program for adults, advocates and providers generally agree that access for children has improved significantly since the implementation of the ARKids First program. ARKids First was created initially in 1997 as a Medicaid expansion program under a Section 1115 waiver before enactment of the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP). The state has opted not to switch its Medicaid expansion program to SCHIP, even though such a change would result in an enhanced federal match of 82 percent, compared with the current 73 percent. To make the change, the state would be required to give up full federal payment for vaccines (under the Vaccines for Children program) as well as forgoing access to the Medicaid drug pricing rebate. Consequently, market observers believe that a switch to SCHIP would not be in the best financial interests of the state.

Two years ago, the state was engaged in a contentious dispute with the federal government over ARKids First. The state, which wanted to allow parents the choice of enrolling their children in either Medicaid or ARKids First, argued that parents, concerned about the stigma associated with Medicaid, preferred the private insurance look-alike offered through ARKids First. Federal rules, however, required that any child eligible for Medicaid should be enrolled there. In 2001, the Medicaid and ARKids First programs were renamed ARKids First A (traditional Medicaid) and ARKids First B (the Medicaid expansion), respectively. Renaming the two programs, together with a simplified enrollment form and removal of the assets tests for children, helped end the dispute.

Enrollment in ARKids First A continues to grow. Between March 2002 and March 2003, enrollment in ARKids First A grew 23 percent (more than 30,000 children), while that in ARKids First B was relatively flat. This growth is attributed in large part to a more streamlined enrollment process. Approximately 235,000 children currently are enrolled in the ARKids First program—177,000 in ARKids First A and 57,000 in ARKids First B.

Although Arkansas’ public insurance programs have been relatively stable in recent years, the state faced revenue shortfalls in fiscal years 2002 and 2003 that resulted in cost-containment mandates across state government. Nevertheless, Arkansas has grappled with a projected budget deficit in excess of $100 million for each year in the 2004 and 2005 biennium (approximately 3% of the state’s total budget), which threatens the status quo of state-funded programs. Gov. Mike Huckabee proposed new taxes to fund the anticipated shortfall. In May 2003, the state legislature approved new taxes on cigarettes, other tobacco products and individual incomes. Potential tightening of eligibility for public programs and restricting benefits is under discussion; however, these new taxes appear to have staved off significant cuts in Medicaid and ARKids First. Although the details remain to be worked out, the state’s willingness to assess new taxes signals its desire to preserve existing public programs.

Despite its budget problems, Arkansas continues to explore mechanisms to expand health insurance coverage. The state recently submitted a waiver under federal Health Insurance Flexibility and Accountability demonstration guidelines to draw on the state’s SCHIP allotment to extend buy-in coverage to uninsured workers and their spouses earning below 200 percent of the federal poverty level. Employers currently not offering insurance would transfer funds to the state, to be matched by the federal government. Other waivers waiting for federal approval include a prescription drug program for elderly Medicare beneficiaries earning below 100 percent of the federal poverty level and a limited benefit for approximately 15,000 food stamp-eligible adults with incomes less than 35 percent of the federal poverty level. These last two waivers propose using part of the state’s tobacco settlement money as the state’s match for federal funds. Even if the waivers receive federal approval, state budget constraints may delay implementation.

Improved Finances, New Capacity Strengthen Safety Net

![]() dvocates and other market observers say that health care services generally are

available to low-income people who seek care. However, access in a broader sense

may be more problematic than perceived due to low expectations and lack of

awareness of safety net services in Little Rock. Some observers also expressed concern

that people do not seek care until the need becomes so acute that, when

care is received, it is often more expensive and less effective than if it had been

provided in a more timely fashion.

dvocates and other market observers say that health care services generally are

available to low-income people who seek care. However, access in a broader sense

may be more problematic than perceived due to low expectations and lack of

awareness of safety net services in Little Rock. Some observers also expressed concern

that people do not seek care until the need becomes so acute that, when

care is received, it is often more expensive and less effective than if it had been

provided in a more timely fashion.

The majority of safety net services in Little Rock are provided by UAMS and Arkansas Children’s Hospital. Two years ago, UAMS, the primary safety net provider in Little Rock for adults, faced major financial deficits. More recently, however, the higher limit on inpatient hospital days paid by Medicaid, coupled with more favorable contractual arrangements with payers and improved patient collections, has led to a financial turnaround and profitability. At the same time, Arkansas Children’s Hospital also improved financially compared to two years ago due mainly to favorable managed care contractual arrangements, an influx of Medicaid upper payment limit and disproportionate share hospital funds and new federal graduate medical education funding provided to children’s hospitals. In addition, the hospital has benefited from a larger number of previously uninsured children now covered through the ARKids First program. Because it is a niche provider of children’s health care services, Children’s is the only hospital in the market that participates in all of the health plans’ networks.

New, though limited, safety net capacity has been added in Little Rock. For example, two new community health centers have opened during the past two years. Jefferson Comprehensive Care System operates these centers (plus an older one) as satellites of its main location in Pine Bluff. In addition, several free clinics are operating in the market, some of which are sponsored by faith-based organizations. Although community advocates note the important safety net role these free clinics play in their neighborhoods, it is unclear to what degree they meet the health care needs of the community, since they have limited capacity and operate only a few hours per week. The safety net is supported as well by the Arkansas Health Care Access Foundation, which offers low-income uninsured individuals access to about 1,000 physicians in the state who have volunteered to see such patients on an occasional basis. The actual number of referrals is very limited—for example, last year the organization referred approximately two patients per physician.

Improved finances and the limited capacity expansions have strengthened Little Rock’s safety net in recent years. Although the state appears to have weathered its current fiscal crisis, continuing budget problems could jeopardize these gains. And the shift by employees may prompt more people to go without health insurance coverage and seek services from the safety net, instead.

Issues to Track

![]() ontinuing increases in premiums could result in a no-win

situation in Little Rock, with employers shifting more costs to employees, who—as

a result—either drop coverage or seek it elsewhere. The market has not

been successful in attracting and maintaining plan competitors, and employers

believe this limited competition has resulted in higher premiums. However, an

unfavorable mix of costs, demographics and local income levels has affected

plan competition adversely as well. While the safety net has strengthened over

the past two years, it may become increasingly taxed if more people find existing

health insurance arrangements, unaffordable, or if the state’s budget problems

worsen.

ontinuing increases in premiums could result in a no-win

situation in Little Rock, with employers shifting more costs to employees, who—as

a result—either drop coverage or seek it elsewhere. The market has not

been successful in attracting and maintaining plan competitors, and employers

believe this limited competition has resulted in higher premiums. However, an

unfavorable mix of costs, demographics and local income levels has affected

plan competition adversely as well. While the safety net has strengthened over

the past two years, it may become increasingly taxed if more people find existing

health insurance arrangements, unaffordable, or if the state’s budget problems

worsen.

Key issues to track include:

Little Rock Consumers’ Access to Care, 2001

Little Rock compared to metropolitan areas with over 200.000 population

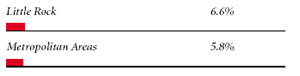

| Unmet Need |

| PERSONS WHO DID NOT GET NEEDED MEDICAL CARE DURING THE LAST 12 MONTHS |

|

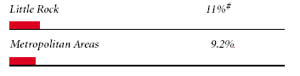

| Delayed Care |

| PERSONS WHO DELAYED GETTING NEEDED MEDICAL CARE DURING THE LAST 12 MONTHS |

|

| Out-of-Pocket Costs |

| PRIVATELY INSURED PEOPLE IN FAMILIES WITH ANNUAL OUT-OF-POCKET COSTS OF $500 OR MORE |

|

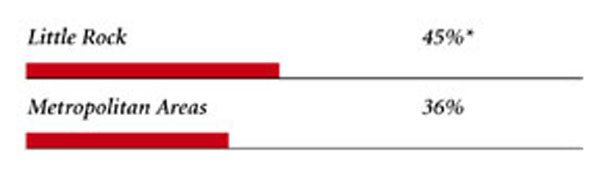

| Access to Physicians |

| PHYSICIANS WILLING TO ACCEPT ALL NEW PATIENTS WITH PRIVATE INSURANCE |

|

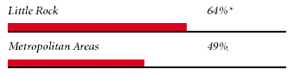

| PHYSICIANS WILLING TO ACCEPT ALL NEW MEDICARE PATIENTS |

|

| PHYSICIANS WILLING TO ACCEPT ALL NEW MEDICAID PATIENTS |

|

| PHYSICIANS PROVIDING CHARITY CARE |

|

| * Site value is significantly different from the mean for large metropolitan

areas over 200,000 population at p<.05. # Indicates a 12-site low. Source: HSC Community Tracking Study Household and Physician Surveys, 2000-01 Note: If a person reported both an unmet need and delayed care, that person is counted as having an unmet need only. Based on follow-up questions asking for reasons for unmet needs or delayed care, data include only responses where at least one of the reasons was related to the health care system. Responses related only to personal reasons were not considered as unmet need or delayed care. |

Background and Observations

| Little Rock Demographics | |

| Little Rock | Metropolitan areas 200,000+ population |

| Population1 590,024 |

|

| Persons Age 65 or Older2 | |

| 11% | 11% |

| Median Family Income2 | |

| $29,688 | $31,883 |

| Unemployment Rate3 | |

| 4.5% | 5.8% |

| Persons Living in Poverty2 | |

| 13% | 12% |

| Persons Without Health Insurance2 | |

| 13% | 13% |

| Age-Adjusted Mortality Rate per 1,000 Population4 | |

| 9.8 | 8.8* |

* National average. Sources: |

|

| Health Care Utilization | |

| Little Rock | Metropolitan areas 200,000 population |

| Adjusted Inpatient Admissions per 1,000 Population 1 | |

| 299 | 180 |

| Persons with Any Emergency Room Visit in Past Year 2 | |

| 20% | 19% |

| Persons with Any Doctor Visit in Past Year 2 | |

| 78% | 78% |

| Average Number of Surgeries in Past Year per 100 Persons 2 | |

| 17 | 17 |

| Sources: 1. American Hospital Association, 2000 2. HSC Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 2000-01 |

|

| Health System Characteristics | |

| Little Rock | Metropolitan areas 200,000+ population |

| Staffed Hospital Beds per 1,000 Population1 | |

| 4.5 | 2.5 |

| Physicians per 1,000 Population2 | |

| 2.4 | 1.9 |

| HMO Penetration, 19993 | |

| 28% | 38% |

| HMO Penetration, 20014 | |

| 21% | 37% |

| Medicare-Adjusted Average per Capita Cost (AAPCC) Rate, 20025 | |

| $553 | $575 |

| Sources: 1. American Hospital Association, 2000 2. Area Resource File, 2002 (includes nonfederal, patient care physicians, except radiologists, pathologists and anesthesiologists) 3. InterStudy Competitive Edge, 10.1 4. InterStudy Competitive Edge, 11.2 5. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Site estimate is payment rate for largest county in site; national estimate is national per capita spending on Medicare enrollees in Coordinated Care Plans in December 2002. |

|