Community Report No. 10

Summer 2003

Ashley C. Short, Jon B. Christianson, Debra A. Draper, Linda R. Brewster, Robert E. Hurley, Richard Sorian, Lawrence D. Brown, Gigi Y. Liu

![]() n April 2003, a team of researchers

visited Phoenix to study that community’s

health system, how it is changing

and the effects of those changes on consumers.

The Center for Studying Health

System Change (HSC), as part of the

Community Tracking Study, interviewed

nearly 100 leaders in the health

care market. Phoenix is one of 12 communities

tracked by HSC every two

years through site visits and every three

years through surveys. Individual community

reports are published for each

round of site visits. The first three site

visits to Phoenix, in 1996, 1998 and

2000, provided baseline and initial trend

information against which changes are

tracked. The Phoenix market includes

Maricopa and Pinal counties.

n April 2003, a team of researchers

visited Phoenix to study that community’s

health system, how it is changing

and the effects of those changes on consumers.

The Center for Studying Health

System Change (HSC), as part of the

Community Tracking Study, interviewed

nearly 100 leaders in the health

care market. Phoenix is one of 12 communities

tracked by HSC every two

years through site visits and every three

years through surveys. Individual community

reports are published for each

round of site visits. The first three site

visits to Phoenix, in 1996, 1998 and

2000, provided baseline and initial trend

information against which changes are

tracked. The Phoenix market includes

Maricopa and Pinal counties.

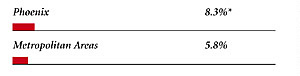

Rapid population growth and a large presence of undocumented immigrants continue to strain health care resources in Phoenix. Rising unemployment, which grew from 2.7 percent in 2000 to 5.7 percent in 2002, has placed additional pressure on health care delivery. Tight hospital and physician capacity is limiting access to care, including emergency care, a key source for uninsured and undocumented residents. To maintain adequate staffing, hospitals are paying more for personnel, contributing to rising costs in the market, and two key safety net facilities are facing financial difficulties.

Other key developments in Phoenix include:

Capacity Constraints Threaten Access to Health Care

![]() he combination of population growth

and medical personnel shortages is

threatening access to care in Phoenix.

Phoenix’s population boom continues,

with the community adding an estimated

100,000 people each year, along with the

continuing influx of undocumented

immigrants coming across the Mexican

border. Although hospitals have invested

millions of dollars in expansion to meet

the needs of the growing population, they

are struggling to find medical personnel

to treat the increasing number of patients.

he combination of population growth

and medical personnel shortages is

threatening access to care in Phoenix.

Phoenix’s population boom continues,

with the community adding an estimated

100,000 people each year, along with the

continuing influx of undocumented

immigrants coming across the Mexican

border. Although hospitals have invested

millions of dollars in expansion to meet

the needs of the growing population, they

are struggling to find medical personnel

to treat the increasing number of patients.

The nursing shortage continues unabated, leaving Arizona hospitals with a ratio of 1.9 nurses employed in acute care settings for each 1,000 of population, compared with 3.3 per 1,000 of population nationwide, according to the Arizona Hospital and Healthcare Association. To open and staff new beds, hospitals are forced to make heavier use of expensive agency or traveling nurses, which adds to cost pressures and sometimes raises concern about the quality of care provided by temporary staff.

The capacity constraints are creating treatment delays in area hospitals. Respondents noted that this has led to delayed elective admissions. Moreover, rural hospital patients awaiting transfer to downtown Phoenix hospitals for specialized care must frequently remain at the rural facilities until space opens up for them.

Strained capacity also is a growing concern in hospital emergency departments. Ambulance diversions rose dramatically during 2001 and declined only slightly in 2002. According to data collected at several hospitals, the number of patients who left emergency departments before getting care also has increased. The nursing shortage has forced some hospitals to take licensed beds out of service, resulting in patients who need admission to medical/surgical or intensive care units remaining in the emergency department until a bed is available. The Arizona Hospital and Healthcare Association estimates that emergency department volume in the state increased 20 percent between 2000 and 2002.

Physician shortages, especially in central Phoenix, mean patients have difficulty scheduling timely appointments in physician offices, with some turning instead to emergency rooms for primary care. Also, observers say that uninsured Phoenix residents, including undocumented immigrants, often go to emergency rooms because they know they will be seen there. Hospitals face significant penalties under the federal Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act, known as EMTALA, if they fail to screen, stabilize and, if necessary, admit emergency patients regardless of their ability to pay.

Specialty physicians’ increasing unwillingness to serve on hospitals’ on-call emergency panels has intensified capacity problems. With some specialists in short supply, physicians may not need to provide emergency department on-call services to fill their practices. Further, many physicians are reluctant to provide on-call services because they don’t get paid for treating uninsured patients but do incur the risk of malpractice suits. With increasing ability to perform procedures outside hospital-owned facilities, some specialists are dropping hospital privileges altogether.

To maintain adequate staffing levels, hospitals have begun to reconfigure their medical staffs in a variety of ways. The use of hospitalists and intensivists is expanding in Phoenix, and hospitals now pay many specialists to provide on-call emergency coverage and sometimes compensate them for emergency services provided to uninsured patients. Paying physicians to ensure on-call emergency department coverage at downtown hospitals had just begun in 2000, but the practice is much more widespread and expensive now. At least one health plan is providing some on-call emergency department coverage to ensure members receive timely treatment.

One illustration of the community’s concern about the adequacy of emergency department capacity was the reaction to Vanguard Health Systems’ decision to convert newly acquired Phoenix Memorial Hospital into a surgery-only hospital and close the facility’s emergency department in November 2002. The facility is located in a low-income area of Phoenix. Community groups expressed concern about the possible impact on access to care, while other hospitals worried about additional strain on their emergency departments. After six months, Vanguard announced that the facility would be converted back to a full-service hospital. Some observers believe that Vanguard was pressured by its own Medicaid managed care health plan, the Phoenix Health Plan, to restore services.

Patients seeking physician care also are experiencing capacity problems. Observers reported a growing shortage of primary care physicians, particularly in downtown Phoenix, where many low-income people live, and some types of specialists. Shortages have resulted in new patients waiting three to four months for appointments with physicians in some specialties. The failure of physician supply to keep up with population growth was attributed to low physician payment rates, a large number of uninsured people and the absence of a medical school in Phoenix.

Hospitals Expand Sites and Specialty Services

![]() he growth opportunities presented by

the booming population have continued

to attract large, national and regional

hospital companies to Phoenix. Banner

Health, a national not-for-profit hospital

system that accounts for about 37 percent

of the inpatient discharges in the market,

has moved its headquarters to Phoenix

and has begun making significant capital

investment there. In the past two years,

Vanguard Health Systems, a national,

for-profit firm that now ranks second in

hospital market share in Phoenix, has

driven consolidation in the market with

the acquisition of two hospitals. Five of

the 15 hospitals owned by Vanguard

nationwide are located in Phoenix. Both

Vanguard and Banner are moving

aggressively to vie for position in the

rapidly growing West Valley through the

construction of new hospitals. Vanguard will

open a 73-bed facility there in September

2003, while Banner plans to open a 164-bed

hospital, now under construction, in

November 2004. Sun Health, a local hospital

system, also owns land in the West Valley

that it could use for expansion.

he growth opportunities presented by

the booming population have continued

to attract large, national and regional

hospital companies to Phoenix. Banner

Health, a national not-for-profit hospital

system that accounts for about 37 percent

of the inpatient discharges in the market,

has moved its headquarters to Phoenix

and has begun making significant capital

investment there. In the past two years,

Vanguard Health Systems, a national,

for-profit firm that now ranks second in

hospital market share in Phoenix, has

driven consolidation in the market with

the acquisition of two hospitals. Five of

the 15 hospitals owned by Vanguard

nationwide are located in Phoenix. Both

Vanguard and Banner are moving

aggressively to vie for position in the

rapidly growing West Valley through the

construction of new hospitals. Vanguard will

open a 73-bed facility there in September

2003, while Banner plans to open a 164-bed

hospital, now under construction, in

November 2004. Sun Health, a local hospital

system, also owns land in the West Valley

that it could use for expansion.

In addition to expanding full-service facilities, some hospital systems are developing specialty hospitals to compete with a growing number of physician-owned specialty facilities in Phoenix. With this year’s opening of the Arizona Spine and Joint Hospital, a joint venture of Chicago-based National Surgical Hospitals and 19 local specialists, Phoenix has three physician-owned specialty hospitals and a number of outpatient facilities. Full-service hospitals fear these physician-owned facilities are siphoning off specialists, insured patients and profitable specialty services, a concern reinforced by a provision in Arizona law that exempts facilities licensed as specialty hospitals from having emergency departments, where uninsured persons might be more likely to seek care. In 2002, the Arizona Hospital and Healthcare Association and local hospitals unsuccessfully sought to eliminate this provision; however, a legislative study committee is now looking at this issue. Health plans have expressed ambivalence about the costs and benefits of stand-alone specialty facilities, contracting with some despite concerns about how they affect full-service hospitals.

In response to the proliferation of physician-owned facilities, several hospital systems have decided to develop freestanding facilities of their own, both to reinforce relationships with particular specialists and to compete for patients. For example, Catholic Healthcare West is forming a partnership with a for-profit company to develop a freestanding orthopedic hospital. Banner already operates a freestanding heart hospital, and Scottsdale Healthcare plans to convert an ambulatory surgery center to an inpatient specialty facility. With hospitals starting to develop their own freestanding specialty hospitals and seeking specialty hospital licenses for these facilities, observers speculated that support for revising the licensure law could wane.

Consumers Face Cost Increases

![]() ith insurance premiums rising between

10 percent and 20 percent annually,

Phoenix-area consumers are shouldering

a heavier cost burden. Two years ago, the

local economy was thriving, the labor

market was tight and employers were less

willing to shift cost increases to employees.

Now that the labor market has softened,

employers are aggressively increasing

consumer cost sharing.

ith insurance premiums rising between

10 percent and 20 percent annually,

Phoenix-area consumers are shouldering

a heavier cost burden. Two years ago, the

local economy was thriving, the labor

market was tight and employers were less

willing to shift cost increases to employees.

Now that the labor market has softened,

employers are aggressively increasing

consumer cost sharing.

Observers attribute rising premiums to a variety of factors. Provider capacity has failed to keep pace with population growth, so providers are more willing to walk away from contracts that do not pay what they want, making it more difficult for plans to negotiate smaller payment rate increases, particularly with hospitals. The widely dispersed population requires plans to maintain broad hospital networks to accommodate members’ needs. Pharmaceutical and other costs, including labor, continue to rise, putting further pressure on prices. Finally, observers say plans have sought to recoup losses from the late 1990s by improving their underwriting and pricing approach and purging unprofitable business. Plans’ financial situations generally have improved since 2000, with all of the major ones posting profits in 2002. One exception is CIGNA Healthcare, which, though still profitable, has seen a major decline in profit margins.

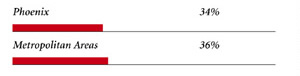

In recent years, the Phoenix health care market has witnessed a steady erosion of demand for health maintenance organizations (HMOs), with market penetration falling from 37 percent in 2001 to 28 percent in 2002, according to InterStudy. Observers generally agreed that many HMO products are now as expensive as or more expensive than preferred provider organization (PPO) products. Frustration with HMOs’ failure to contain costs has led to migration to open-access HMOs with broad networks and PPOs. A major beneficiary of this trend has been Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Arizona, the plan with the largest enrollment in their PPO product in the market.

Public Coverage Expands, but Budget Crisis Forces Cuts

![]() ften portrayed as a model to other

states, AHCCCS is a well-established

program with more than 20 years of

experience in Medicaid managed care. In

2000, Arizona voters overwhelmingly

approved a ballot initiative, known as

Proposition 204, to earmark the state’s

tobacco settlement monies to expand

adult eligibility levels for Medicaid from

33 percent of the federal poverty level to

100 percent. In January 2003, parents of

children enrolled in SCHIP became eligible

for coverage under a Health Insurance

Flexibility and Accountability, or HIFA,

waiver. These new coverage initiatives,

plus additional outreach efforts in 2000

and 2001 and the worsening economy,

have fueled AHCCCS growth. Enrollment

jumped from about 550,000 to 905,000

beneficiaries in the last two years, and

AHCCCS now covers about 17 percent of

Arizona’s population. In spite of coverage

expansions, observers say the proportion

of uninsured people in the state has not

declined markedly because of the weak

economy and continued population growth.

ften portrayed as a model to other

states, AHCCCS is a well-established

program with more than 20 years of

experience in Medicaid managed care. In

2000, Arizona voters overwhelmingly

approved a ballot initiative, known as

Proposition 204, to earmark the state’s

tobacco settlement monies to expand

adult eligibility levels for Medicaid from

33 percent of the federal poverty level to

100 percent. In January 2003, parents of

children enrolled in SCHIP became eligible

for coverage under a Health Insurance

Flexibility and Accountability, or HIFA,

waiver. These new coverage initiatives,

plus additional outreach efforts in 2000

and 2001 and the worsening economy,

have fueled AHCCCS growth. Enrollment

jumped from about 550,000 to 905,000

beneficiaries in the last two years, and

AHCCCS now covers about 17 percent of

Arizona’s population. In spite of coverage

expansions, observers say the proportion

of uninsured people in the state has not

declined markedly because of the weak

economy and continued population growth.

Despite the dramatic enrollment increases, health plan participation in Medicaid managed care remains stable. Some plans complained that AHCCCS did not adjust rates appropriately for the Proposition 204 enrollees, who, some observers said, had higher-than-expected medical needs. CIGNA Healthcare cited low reimbursement as one factor in its recent decision to drop out of the program. However, the five other plans will continue to participate in Maricopa County, along with a new contractor, Care1st. Observers say that AHCCCS physician payments are comparable to Medicare, and, as a result, physician participation remains strong.

The rapid growth of the AHCCCS program has come at a difficult time for the state, which as of April 2003 was facing a projected $1 billion shortfall for 2004, or nearly 17 percent of the state’s $6 billion budget. Concerns about how the state would continue to fund the Proposition 204 expansion led to Proposition 303, passed by voters in 2002, which increased the state’s tobacco excise tax by 60 cents a pack to fund health care initiatives for low-income people. In spite of the increased funding, some state legislators have expressed interest in repealing Proposition 204, which would require a two-thirds vote of the Legislature.

Thus, lawmakers have targeted other areas for cuts. Newly elected Gov. Janet Napolitano is supportive of health programs for families and children, but the Legislature is less so. Term limits have sparked concerns that the loss of institutional knowledge about publicly sponsored health programs within the Legislature could make such programs vulnerable to cuts. Ultimately, budget cuts were not as deep as expected, due in part to the infusion of $350 million into the state as part of federal tax cut legislation. However, a number of programs were eliminated or scaled back, including a premium-sharing program that served about 2,500 low-income workers. Coverage for roughly 10,000 parents enrolled in SCHIP is slated to end June 30, 2004. In addition, the new budget requires AHCCCS to determine member eligibility every six months instead of annually and increases cost sharing for AHCCCS members.

Safety Net Hospitals Falter

![]() s safety net hospitals struggle, community

health centers (CHCs) have benefited

from new federal funding. Job losses—and

the concurrent loss of health insurance—

along with the continued influx of

undocumented immigrants, have increased

demand for free or reduced-cost care at the

same time local safety net hospitals are

struggling financially.

s safety net hospitals struggle, community

health centers (CHCs) have benefited

from new federal funding. Job losses—and

the concurrent loss of health insurance—

along with the continued influx of

undocumented immigrants, have increased

demand for free or reduced-cost care at the

same time local safety net hospitals are

struggling financially.

One major threat to access to care for the uninsured is the dire financial status of the county-owned Maricopa Integrated Health System (MIHS), which includes 541-bed Maricopa Medical Center (MMC), a behavioral health facility, a number of health centers and a health plan. The predominant safety net provider in the market, MMC was in the red in 2002, and prospects for 2003 look equally bleak. Observers cited various reasons for the system’s deteriorating financial condition, including the loss of some funding streams. MIHS used to be the exclusive provider for the Arizona long-term care system in Maricopa County but is now one of three contractors. In addition, the system lost disproportionate share hospital funds due to recent changes in federal regulations. A general county subsidy also was cut by 10 percent this year. And state monies to fund emergency care for the uninsured have been eliminated in 2003, just as uncompensated care at the hospital is increasing. Finally, the physical plant requires extensive renovation, and, as a result, MMC has difficulty attracting better-paying, private patients.

The state Legislature recently approved a ballot initiative to create a special hospital taxing district to support MIHS. Continuing the status quo, hospital leaders argue, could bankrupt the county, but closure would worsen capacity problems for many of Phoenix’s remaining hospitals, severely reduce physician residency training capacity in a state that is already struggling with a growing physician shortage and eliminate a vital component of the safety net. In fact, the Arizona Hospital and Healthcare Association, which opposed previous attempts to create a taxing district out of concern for the competitive impact on other hospitals in the market, now supports the taxing district as long as MIHS does not expand its current geographic scope.

Phoenix Children’s Hospital, the only pediatric specialty hospital in the market and a major safety net provider, also is in serious financial trouble as a result of construction cost overruns, management problems, poor payer mix and storm damage that disrupted operations for an extended period. Several other hospitals in the market also offer pediatric services, but Phoenix Children’s reportedly offers some pediatric services unique to the market.

The outlook for community health centers in Phoenix is comparatively brighter than for the area’s safety net hospitals. The two federally qualified health centers in the market—Mountain Park and Clinica Adelante—have used new federal funding for expansion, adding sites, services, staff and hours. CHCs are included in most AHCCCS plans’ provider networks and have benefited from the Medicaid and SCHIP coverage expansions in recent years because many previously uninsured patients are now covered through AHCCCS. However, CHCs fear that state budget problems, should they continue, could threaten their fiscal future.

Issues to Track

![]() he Phoenix market continues to grapple

with the demands of a booming population

during an economic downturn, and

crowded conditions threaten access to

care. At the same time, consumer cost

sharing is rising. Key safety net facilities’

precarious financial positions could

threaten access to care for the uninsured

in Phoenix. And, although AHCCCS

enrollment has expanded over the past

two years, a budget crisis has triggered

cuts in some public programs.

he Phoenix market continues to grapple

with the demands of a booming population

during an economic downturn, and

crowded conditions threaten access to

care. At the same time, consumer cost

sharing is rising. Key safety net facilities’

precarious financial positions could

threaten access to care for the uninsured

in Phoenix. And, although AHCCCS

enrollment has expanded over the past

two years, a budget crisis has triggered

cuts in some public programs.

The following issues are important to track:

Phoenix Consumers’ Access to Care, 2001

Phoenix compared to metropolitan areas with over 200,000 population

| Unmet Need |

| PERSONS WHO DID NOT GET NEEDED MEDICAL CARE DURING THE LAST 12 MONTHS |

|

| Delayed Care |

| PERSONS WHO DELAYED GETTING NEEDED MEDICAL CARE DURING THE LAST 12 MONTHS |

|

| Out-of-Pocket Costs |

| PRIVATELY INSURED PEOPLE IN FAMILIES WITH ANNUAL OUT-OF-POCKET COSTS OF $500 OR MORE |

|

| Access to Physicians |

| PHYSICIANS WILLING TO ACCEPT ALL NEW PATIENTS WITH PRIVATE INSURANCE |

|

| PHYSICIANS WILLING TO ACCEPT ALL NEW MEDICARE PATIENTS |

|

| PHYSICIANS WILLING TO ACCEPT ALL NEW MEDICAID PATIENTS |

|

| PHYSICIANS PROVIDING CHARITY CARE |

|

| * Site value is significantly different from the mean for large metropolitan

areas over 200,000 population at p<.05. Source: HSC Community Tracking Study Household and Physician Surveys, 2000-01 Note: If a person reported both an unmet need and delayed care, that person is counted as having an unmet need only. Based on follow-up questions asking for reasons for unmet needs or delayed care, data include only responses where at least one of the reasons was related to the health care system. Responses related only to personal reasons were not considered as unmet need or delayed care. |

Background and Observations

| Phoenix Demographics | |

| Phoenix | Metropolitan Areas 200,000+ Population |

| Population1 3,383,644 |

|

| Persons Age 65 or Older2 | |

| 12% | 11% |

| Median Family Income2 | |

| $25,810 | $31,883 |

| Unemployment Rate3 | |

| 5.7% | 5.8%* |

| Persons Living in Poverty2 | |

| 14% | 12% |

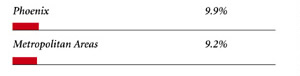

| Persons Without Health Insurance2 | |

| 19% | 13% |

| Age-Adjusted Mortality Rate per 1,000 Population4 | |

| 8.4 | 8.8* |

* National average. Sources: |

|

| Health Care Utilization | |

| Phoenix | Metropolitan Areas 200,000+ Population |

| Adjusted Inpatient Admissions per 1,000 Population 1 | |

| 148 | 180 |

| Persons with Any Emergency Room Visit in Past Year 2 | |

| 17% | 19% |

| Persons with Any Doctor Visit in Past Year 2 | |

| 71% | 78% |

| Average Number of Surgeries in Past Year per 100 Persons 2 | |

| 17 | 17 |

| Sources: 1. American Hospital Association, 2000 2. HSC Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 2000-01 |

|

| Health System Characteristics | |

| Phoenix | Metropolitan Areas 200,000+ Population |

| Staffed Hospital Beds per 1,000 Population1 | |

| 1.9 | 2.5 |

| Physicians per 1,000 Population2 | |

| 1.4 | 1.9 |

| HMO Penetration, 19993 | |

| 34% | 38% |

| HMO Penetration, 20014 | |

| 37% | 37% |

| Medicare-Adjusted Average per Capita Cost (AAPCC) Rate, 20025 | |

| $553 | $575 |

| Sources: 1. American Hospital Association, 2000 2. Area Resource File, 2002 (includes nonfederal, patient care physicians, except radiologists, pathologists and anesthesiologists) 3. InterStudy Competitive Edge, 10.1 4. InterStudy Competitive Edge, 11.2 5. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Site estimate is payment rate for largest county in site; national estimate is national per capita spending on Medicare enrollees in Coordinated Care Plans in December 2002. |

|

The Community Tracking Study, the major effort of the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC), tracks changes in the health system in 60 sites that are representative of the nation. HSC conducts surveys in all 60 communities every three years and site visits in 12 communities every two years. This Community Report series documents the findings from the fourth round of site visits. Analyses based on site visit and survey data from the Community Tracking Study are published by HSC in Issue Briefs, Tracking Reports, Data Bulletins and peer-reviewed journals. These publications are available at www.hschange.org.

Authors of the Phoenix Community Report:

Ashley C. Short, HSC; Jon B. Christianson, University of Minnesota; Debra

A. Draper, Mathematica Policy Research, Inc.; Linda R. Brewster, HSC; Robert

E. Hurley, Commonwealth University; Richard Sorian, HSC; Lawrence D. Brown,

Columbia University; Gigi Y. Liu, HSC

Community Reports are published by HSC:

President: Paul B. Ginsburg

Director of Site Visits: Cara S. Lesser

Editor: The Stein Group

For additional copies or to be added to the mailing list, contact HSC at:

600 Maryland Avenue SW, Suite 550, Washington, DC 20024-2512

Tel: (202) 554-7549 (for publication information)

Tel: (202) 484-5261 (for general HSC information)

Fax: (202) 484-9258

www.hschange.org