Community Report No. 11

Summer 2003

Glen P. Mays, Sally Trude, Lawrence P. Casalino, Laurie E. Felland, Gary Claxton, Megan McHugh, Hoangmai H. Pham, Jessica H. May

![]() n April 2003, a team of researchers

visited Miami to study that community’s

health system, how it is changing and

the effects of those changes on consumers.

The Center for Studying Health System

Change (HSC),as part of the Community

Tracking Study, interviewed more than

70 leaders in the health care market.

Miami is one of 12 communities tracked

by HSC every two years through site

visits and every three years through

surveys. Individual community reports

are published for each round of site visits.

The first three site visits to Miami, in

1997, 1999 and 2001, provided baseline

and initial trend information against

which changes are tracked. The Miami

market encompasses Miami-Dade County.

n April 2003, a team of researchers

visited Miami to study that community’s

health system, how it is changing and

the effects of those changes on consumers.

The Center for Studying Health System

Change (HSC),as part of the Community

Tracking Study, interviewed more than

70 leaders in the health care market.

Miami is one of 12 communities tracked

by HSC every two years through site

visits and every three years through

surveys. Individual community reports

are published for each round of site visits.

The first three site visits to Miami, in

1997, 1999 and 2001, provided baseline

and initial trend information against

which changes are tracked. The Miami

market encompasses Miami-Dade County.

Rapidly rising health insurance premiums and a worsening medical malpractice insurance climate threaten to decrease health insurance coverage and access to health care in Miami. Health plans have continued to move away from aggressive price competition over the past two years, and a shift toward less restrictive health insurance products has contributed to increased health care utilization and costs. Adding to these cost pressures, hospitals have continued to press for payment rate increases, and a growing medical malpractice insurance crisis has led physicians to adopt more defensive approaches to clinical practice, including referring more patients to hospital settings.

Other developments in Miami include:

- Sharp Premium Increases Challenge Employers

- Malpractice Insurance Crisis Prompts Physician Practice Changes

- Hospital Capacity Constraints Intensify in Miami

- Safety Net Expands but Disputes Remain

- Issues to Track

- Medicare+Choice Evolution

- Miami Consumers’ Access to Care, 2001

- Background and Observations

Sharp Premium Increases Challenge Employers

![]() he Miami market has experienced steep increases in commercial

health insurance premiums over the past two years as health plans moved to restore

profitability at the same time health care use and cost trends were rising.

For example, premiums have increased 20 percent to 50 percent over the past

year—faster than in many other markets across the country. Single-year premium

hikes have left even the largest Miami employers struggling to adapt. For example,

the Miami-Dade School District’s 2003 premium increases forced the school system

to drop its flexible benefit plan that included dependent coverage, dental,

vision and other benefits and replace it with a small monthly contribution toward

dependent coverage.

he Miami market has experienced steep increases in commercial

health insurance premiums over the past two years as health plans moved to restore

profitability at the same time health care use and cost trends were rising.

For example, premiums have increased 20 percent to 50 percent over the past

year—faster than in many other markets across the country. Single-year premium

hikes have left even the largest Miami employers struggling to adapt. For example,

the Miami-Dade School District’s 2003 premium increases forced the school system

to drop its flexible benefit plan that included dependent coverage, dental,

vision and other benefits and replace it with a small monthly contribution toward

dependent coverage.

Aggressive price competition among numerous insurers in Miami’s fragmented market held annual premium increases below medical cost trends for much of the past six years, perhaps in part because Miami’s large Medicare+Choice market historically allowed some plans to offset losses on commercial products with profits from Medicare+Choice (see box on page 3). Over the past two years, however, declining Medicare+Choice profit margins and deepening losses on commercial products led most plans to forgo aggressive price competition and increase premiums to assure profitability. Because underlying medical costs have increased considerably over this same period, the result has been large premium spikes.

Recent changes in health plan design have contributed to Miami’s sharp premium increases. Health maintenance organizations (HMOs) dominated Miami’s health insurance market for most of the past decade, but over the past two years commercial enrollment has shifted to less restrictive but more costly designs that allow consumers to access a broader choice of providers and to escape primary care gatekeeping and prior authorization requirements. In 1998, UnitedHealthcare was the first plan to offer an open-access HMO product in Miami, which remains popular despite United’s raising premiums annually by an average of 30 percent over the past two years. Other health plans have developed similar products over the past two years as well.

Employers have responded to rising insurance premiums in varying ways, including increasing employee premium contributions, increasing copayments, moving to coinsurance designs where patients pay a percentage of the total bill rather than a fixed-dollar amount and switching to lower-priced health plans. Additionally, some Miami employers have begun to assist workers in obtaining coverage for children through KidCare, Florida’s Medicaid and State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP). For example, the Miami-Dade School District provides price comparisons and KidCare enrollment information on its Web site. In addition, because a child has to be uninsured at the time of enrollment in Healthy Kids, the SCHIP component of KidCare, the school district has instituted a policy allowing an employee to enroll a child in the district-sponsored health plan after the open enrollment deadline if the child turned out to be ineligible for Healthy Kids. There also are several local efforts to help employers promote KidCare enrollment among their employees’ families. For example, the local chamber of commerce mailed information about KidCare to 6,000 small employers, and the Miami-Dade County Health Department has begun working with other local partners to call small businesses and notify them of KidCare.

Malpractice Insurance Crisis Prompts Physician Practice Changes

![]() he rising cost of malpractice liability insurance in Miami

has prompted growing numbers of physicians to drop their coverage and adopt

more defensive practice styles that threaten to increase health care costs and

diminish access to care. Several medical groups reported that their malpractice

premiums more than doubled over the past two years. Many of Miami’s obstetricians

have practiced without coverage since the last malpractice insurance crisis

in the 1980s, but now many other surgical specialists, and even some primary

care physicians, have dropped coverage because of the cost. In response to the

growing malpractice insurance crisis, some health plans and many hospitals have

modified credentialing policies so as not to exclude physicians who lack liability

coverage.

he rising cost of malpractice liability insurance in Miami

has prompted growing numbers of physicians to drop their coverage and adopt

more defensive practice styles that threaten to increase health care costs and

diminish access to care. Several medical groups reported that their malpractice

premiums more than doubled over the past two years. Many of Miami’s obstetricians

have practiced without coverage since the last malpractice insurance crisis

in the 1980s, but now many other surgical specialists, and even some primary

care physicians, have dropped coverage because of the cost. In response to the

growing malpractice insurance crisis, some health plans and many hospitals have

modified credentialing policies so as not to exclude physicians who lack liability

coverage.

Physicians and medical groups have developed a variety of strategies for coping with the malpractice insurance problem. Other than a Florida law requiring physicians without malpractice coverage to post a sign in their offices informing patients that they have assets sufficient to pay at least $250,000 of any malpractice award, there are few barriers to physicians practicing without coverage. Because Florida’s bankruptcy laws provide protection for homes and personal assets held in a spouse’s name, many physicians reportedly consider bankruptcy the most viable strategy for responding to a large malpractice award. At least one single-specialty medical group is establishing its own insurance company to provide its physicians with malpractice liability coverage—a strategy that several area hospitals also have pursued.

Many observers noted that the growing cost of malpractice coverage has prompted physicians to adopt more defensive approaches to clinical practice, thereby contributing to increases in health care utilization and costs. Over the past two years, Miami physicians reportedly have become more likely to refer patients to hospital emergency departments rather than treat them in their offices, and emergency department physicians have become more likely to admit patients to the hospital rather than treat them on an outpatient basis. Physicians reportedly have become more reluctant to serve as attending physicians for hospitalized patients, to be on call in hospital emergency departments, to provide nonobstetrical consultations for pregnant women with other medical conditions and to serve Medicaid and uninsured patients because of perceptions that these patients are more likely to file malpractice claims. Respondents also noted that the recent growth in utilization of diagnostic and imaging services is attributable at least in part to physicians’ increasingly defensive practice styles.

Other problems triggered by the malpractice insurance situation include difficulty recruiting physicians to the Miami area and growing physician dissatisfaction with their practice environment. Commercial health insurance payment rates to physicians have remained low in Miami at 70 percent to 80 percent of Medicare rates, making the high cost of malpractice insurance and the risk of malpractice lawsuits especially troublesome to physicians.

Many market observers are looking to state policy makers to resolve the medical malpractice insurance problem in the short term. Both houses of the Florida Legislature have passed bills that would place caps on the damages awarded in malpractice suits, but as of July 2003 legislators have been unable to reach agreement on the level of these caps. Gov. Jeb Bush has called several special sessions of the Legislature to resolve the differences, but some observers maintain that neither version of the legislation would constrain malpractice insurance costs significantly.

Hospital Capacity Constraints Intensify in Miami

![]() apacity constraints have intensified in Miami’s most prominent

hospitals over the past two years, threatening to compromise timely access to

care for area residents. Physicians report increased difficulty in admitting

patients to these hospitals, and many hospital emergency departments are overflowing,

resulting in patients waiting longer to receive care. Baptist Hospital experienced

a 7 percent increase in inpatient admission days during early 2003 despite operating

at full capacity during 2002. One of HCA’s facilities, Aventura Hospital, has

placed its emergency department on diversion status on a regular basis due to

capacity constraints—nearly once a week during the peak winter season.

apacity constraints have intensified in Miami’s most prominent

hospitals over the past two years, threatening to compromise timely access to

care for area residents. Physicians report increased difficulty in admitting

patients to these hospitals, and many hospital emergency departments are overflowing,

resulting in patients waiting longer to receive care. Baptist Hospital experienced

a 7 percent increase in inpatient admission days during early 2003 despite operating

at full capacity during 2002. One of HCA’s facilities, Aventura Hospital, has

placed its emergency department on diversion status on a regular basis due to

capacity constraints—nearly once a week during the peak winter season.

Hospital capacity constraints have grown more severe for a variety of reasons, according to local observers, including an overall increase in hospital admissions, more instances of physicians referring patients to emergency departments due to malpractice concerns, a growing reluctance of physicians to serve as consulting or admitting physicians for emergency department patients and persistent shortages of nurses and other hospital staff. Health plans indicated that capacity constraints have been aggravated by a recent state law that limits an insurer’s ability to deny coverage for hospital admissions when patients are admitted from an emergency department. Moreover, the state’s strong certificate-of-need (CON) laws were viewed by hospitals as slowing construction of new and expanded facilities that could help alleviate capacity problems. Each of the major hospital systems has CON applications in process for new beds, including critical care, emergency department, telemetry and medical/surgical beds, and two systems have CON applications for the construction of new hospitals.

While capacity constraints have created logistical difficulties for the area’s most prominent hospitals and their patients, the constraints also have benefited these facilities by strengthening their negotiating leverage with health plans. Hospitals operating at full capacity with excess demand for their services have little reason to offer payment concessions to health plans. These hospitals include those within the Baptist Hospital System—long regarded as an essential component of a health plan’s network due to its reputation and dominance in southern Dade County—as well as the HCA and Tenet systems, which operate multiple facilities in the market.

Although hospitals have used their increased negotiating leverage to secure higher payment rates—and profit margins —from health plans over the past two years, most respondents indicated that increased utilization, rather than higher prices, has been the most important factor in higher spending on hospital services. Interestingly, health plans have benefited from the hospital expansion proposals currently under review in the CON process because this has made hospitals more concerned about their public image and reluctant to press health plans aggressively for higher payment rates. As a consequence, perhaps, contracting disputes between health plans and hospitals have become less frequent and less intense in Miami than they were two years ago.

Safety Net Expands but Disputes Remain

![]() xpansions by Miami’s primary safety net hospital system,

Jackson Health System, and area community health centers (CHCs) have strengthened

the health care safety net, helping providers respond to more people receiving

charity care over the past two years. Jackson expanded into southern Miami-Dade

County by acquiring Deering Hospital in 2001. The lack of a presence in southern

Miami-Dade had been a major source of criticism for Jackson and the Public Health

Trust, a quasigovernmental body that oversees the hospital. More recently, the

Public Health Trust started a pilot program designed to provide comprehensive

health care services for 1,500 low-income uninsured people, mostly in the underserved

area of southern Miami-Dade. Although the pilot program is small compared to

the number of uninsured in the county, the Public Health Trust reportedly would

like to expand the program significantly. Jackson also has loosened restrictions

on serving undocumented immigrants over the past two years.

xpansions by Miami’s primary safety net hospital system,

Jackson Health System, and area community health centers (CHCs) have strengthened

the health care safety net, helping providers respond to more people receiving

charity care over the past two years. Jackson expanded into southern Miami-Dade

County by acquiring Deering Hospital in 2001. The lack of a presence in southern

Miami-Dade had been a major source of criticism for Jackson and the Public Health

Trust, a quasigovernmental body that oversees the hospital. More recently, the

Public Health Trust started a pilot program designed to provide comprehensive

health care services for 1,500 low-income uninsured people, mostly in the underserved

area of southern Miami-Dade. Although the pilot program is small compared to

the number of uninsured in the county, the Public Health Trust reportedly would

like to expand the program significantly. Jackson also has loosened restrictions

on serving undocumented immigrants over the past two years.

Miami’s CHCs and other community-based organizations also have expanded service offerings and outreach activities for the uninsured over the past two years. With the support of federal expansion grants, several health centers have added services, including dental, school-based and mental health services. Additionally,Miami’s safety net providers launched a program designed to link uninsured patients with available public insurance programs and to coordinate the health care delivered to uninsured patients across multiple sources of care. This program, administered by Jackson through a federal Community Access Program (CAP) grant, reportedly has helped the health system develop stronger relationships with CHCs and other sources of care for underserved populations. Some CHCs also have benefited from a growing interest among physicians in practicing in health center clinics, which can offer physicians immunity from malpractice claims.

Expanding safety net capacity in Miami has done little to diminish the debate surrounding the distribution of the county’s indigent care funds. For years, area providers have criticized the fact that all of the indigent care revenue raised through a half-cent county sales tax is earmarked for the Public Health Trust—which in turn allocates most of the funding to Jackson—even though other hospitals and health centers provide charity care in the county. While the Public Health Trust has allocated some tax funding to other area providers, such as CHCs, and contributes to the local match required for SCHIP, other local providers would like to see the Trust’s authority and funding distributed more broadly to other organizations. In 2001, a state law that directed the county to use the funds to support a countywide plan for the uninsured was ruled unconstitutional, thereby ending a lawsuit brought by seven local hospitals to force compliance with the law. While leadership at the Public Health Trust has been shaken up and Jackson has expanded services throughout the county, there has been no significant change in indigent care fund allocations.

To address concerns about the local safety net,Miami-Dade County Mayor Alex Penelas created a health care task force to examine strategies for improving the existing delivery system and expanding insurance coverage options for the uninsured. The task force’s recommendations included creating a new governance structure outside the Public Health Trust to plan and coordinate health care programs that improve access to care and developing a subsidized insurance program providing limited benefits for uninsured people through their employers. Many community observers are optimistic that the mayor’s efforts have created an impetus for significant improvements in access throughout Miami. In fact, the Miami-Dade County Commission recently unveiled a proposal to downsize the Public Health Trust and transfer countywide planning responsibilities to a new county office. However, whether the task force’s plans come to fruition or the Public Health Trust/Jackson Health System continues to expand its reach remains to be seen.

Unlike in many other communities, looming state and local budget cuts do not appear to pose as serious a threat to Miami’s safety net. Sales tax revenues for the county’s indigent care fund have remained relatively stable despite the economic downturn, but greater numbers of people seeking care have challenged some local safety net providers. At the state level, Florida’s budget gap is less severe than that of many other states, perhaps due in part to the absence of a state personal income tax, which can produce large fluctuations in revenue streams, and to Medicaid cuts enacted a few years ago. Additionally, over the past two years, the state has instituted a Medicaid drug formulary and some relatively minor funding cuts to Medicaid, and several additional cost containment measures are anticipated for Medicaid and Healthy Kids in the upcoming year.

Issues to Track

![]() n increasingly severe malpractice insurance crisis has

driven up hospital admissions and emergency room use while leading physicians

to be more selective about the patients they treat. Growing hospital and health

plan profitability and sharp premium increases raise questions about the continued

affordability of insurance coverage for many Miami employers and consumers.

Although safety net capacity has expanded, it is unlikely that providers could

absorb a substantial increase in Miami’s uninsured population, which already

numbers half a million people.

n increasingly severe malpractice insurance crisis has

driven up hospital admissions and emergency room use while leading physicians

to be more selective about the patients they treat. Growing hospital and health

plan profitability and sharp premium increases raise questions about the continued

affordability of insurance coverage for many Miami employers and consumers.

Although safety net capacity has expanded, it is unlikely that providers could

absorb a substantial increase in Miami’s uninsured population, which already

numbers half a million people.

Issues to track include:

Medicare+Choice Evolution

![]() n contrast to many other communities, the Medicare+Choice

market in Miami has remained viable and competitive over the past two years,

although health plans have scaled back benefits to remain profitable. Miami

enjoys one of the highest Medicare+Choice payment rates in the nation, but caps

on payment increases in the federal Balanced Budget Act of 1997 (BBA) have reduced

the profitability of these products. Historically,Medicare HMOs were so profitable

in Miami that plans were willing to sell their commercial products at a loss

to meet the Medicare requirement of maintaining at least 50 percent of their

membership in commercial products—a practice that was abandoned after 1997,

when the BBA eliminated this rule. Plans continue to offer zero-premium Medicare+Choice

products in Miami, but have scaled back or eliminated prescription drug benefits

and have increased cost sharing for services such as hospitalizations, emergency

department visits and outpatient surgery and diagnostic services.

n contrast to many other communities, the Medicare+Choice

market in Miami has remained viable and competitive over the past two years,

although health plans have scaled back benefits to remain profitable. Miami

enjoys one of the highest Medicare+Choice payment rates in the nation, but caps

on payment increases in the federal Balanced Budget Act of 1997 (BBA) have reduced

the profitability of these products. Historically,Medicare HMOs were so profitable

in Miami that plans were willing to sell their commercial products at a loss

to meet the Medicare requirement of maintaining at least 50 percent of their

membership in commercial products—a practice that was abandoned after 1997,

when the BBA eliminated this rule. Plans continue to offer zero-premium Medicare+Choice

products in Miami, but have scaled back or eliminated prescription drug benefits

and have increased cost sharing for services such as hospitalizations, emergency

department visits and outpatient surgery and diagnostic services.

Although no health plans have withdrawn from the Medicare+Choice market over the past two years, the retooling of benefits and provider networks has resulted in some significant shifts in Medicare enrollment and market share. Perhaps the biggest change occurred in 2002 when UnitedHealthcare lost more than half of its Medicare+Choice members to a competing health plan after a large group of medical clinics withdrew from United’s provider network. Many of United’s Medicare+Choice members who used the clinics then switched to another health plan to continue accessing these providers. Two other large health plans—Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Florida and AvMed Health Plan—lost significant numbers of Medicare+Choice members when they eliminated or reduced prescription drug coverage in 2002 to stem financial losses. In both cases, Medicare members moved to competing health plans with more generous benefits.

National carrier Humana Medical Plan has remained the market’s largest Medicare+Choice health plan with approximately 140,000 members in south Florida, while local plan Neighborhood Health Partnership has increased its Medicare enrollment significantly over the past two years to become the second-largest plan in Miami. Despite the current success of Medicare+Choice health plans, many observers expect these plans will become increasingly difficult to sustain in the future as health care costs continue to rise faster than plan payments.

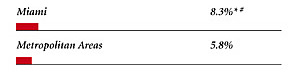

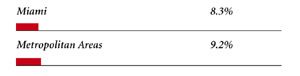

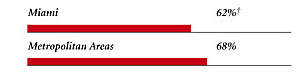

Miami Consumers’ Access to Care, 2001

Miami compared to metropolitan areas with over 200,000 population

| Unmet Need |

| PERSONS WHO DID NOT GET NEEDED MEDICAL CARE DURING THE LAST 12 MONTHS |

|

| Delayed Care |

| PERSONS WHO DELAYED GETTING NEEDED MEDICAL CARE DURING THE LAST 12 MONTHS |

|

| Out-of-Pocket Costs |

| PRIVATELY INSURED PEOPLE IN FAMILIES WITH ANNUAL OUT-OF-POCKET COSTS OF $500 OR MORE |

|

| Access to Physicians |

| PHYSICIANS WILLING TO ACCEPT ALL NEW PATIENTS WITH PRIVATE INSURANCE |

|

| PHYSICIANS WILLING TO ACCEPT ALL NEW MEDICARE PATIENTS |

|

| PHYSICIANS WILLING TO ACCEPT ALL NEW MEDICAID PATIENTS |

|

| PHYSICIANS PROVIDING CHARITY CARE |

|

| * Site value is significantly different from the mean for large

metropolitan areas over 200,000 population at p<.05. # Indicates a 12-site high. † Indicates a 12-site low. Source: HSC Community Tracking Study Household and Physician Surveys, 2000-01 Note: If a person reported both an unmet need and delayed care, that person is counted as having an unmet need only. Based on follow-up questions asking for reasons for unmet needs or delayed care, data include only responses where at least one of the reasons was related to the health care system. Responses related only to personal reasons were not considered as unmet need or delayed care. |

Background and Observations

| Miami Demographics | |

| Miami | Metropolitan Areas 200,000+ Population |

| Population1 2,289,683 |

|

| Persons Age 65 or Older2 | |

| 13% | 11% |

| Median Family Income2 | |

| $19,978 | $31,883 |

| Unemployment Rate3 | |

| 7.7% | 5.8%* |

| Persons Living in Poverty2 | |

| 22% | 12% |

| Persons Without Health Insurance2 | |

| 24% | 13% |

| Age-Adjusted Mortality Rate per 1,000 Population4 | |

| 8.0 | 8.8* |

* National average. Sources: |

|

| Health Care Utilization | |

| Miami | Metropolitan Areas 200,000+ Population |

| Adjusted Inpatient Admissions per 1,000 Population 1 | |

| 207 | 180 |

| Persons with Any Emergency Room Visit in Past Year 2 | |

| 15% | 19% |

| Persons with Any Doctor Visit in Past Year 2 | |

| 72% | 78% |

| Average Number of Surgeries in Past Year per 100 Persons 2 | |

| 13 | 17 |

| Sources: 1. American Hospital Association, 2000 2. HSC Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 2000-01 |

|

| Health System Characteristics | |

| Miami | Metropolitan Areas 200,000+ Population |

| Staffed Hospital Beds per 1,000 Population1 | |

| 3.6 | 2.5 |

| Physicians per 1,000 Population2 | |

| 2.3 | 1.9 |

| HMO Penetration, 19993 | |

| 52% | 38% |

| HMO Penetration, 20014 | |

| 42% | 37% |

| Medicare-Adjusted Average per Capita Cost (AAPCC) Rate, 20025 | |

| $834 | $575 |

| Sources: 1. American Hospital Association, 2000 2. Area Resource File, 2002 (includes nonfederal, patient care physicians, except radiologists, pathologists and anesthesiologists) 3. InterStudy Competitive Edge, 10.1 4. InterStudy Competitive Edge, 11.2 5. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Site estimate is payment rate for largest county in site; national estimate is national per capita spending on Medicare enrollees in Coordinated Care Plans in December 2002. |

|

The Community Tracking Study, the major effort of the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC), tracks changes in the health system in 60 sites that are representative of the nation. HSC conducts surveys in all 60 communities every three years and site visits in 12 communities every two years. This Community Report series documents the findings from the fourth round of site visits. Analyses based on site visit and survey data from the Community Tracking Study are published by HSC in Issue Briefs, Tracking Reports, Data Bulletins and peer-reviewed journals. These publications are available at www.hschange.org.

Authors of the Miami Community Report:

Glen P. Mays, Mathematica Policy Research, Inc.;

Sally Trude, HSC; Lawrence P. Casalino, University of Chicago;

Laurie E. Felland, HSC; Gary Claxton, Kaiser Family Foundation;

Megan McHugh, Mathematica Policy Research, Inc.;

Hoangmai H. Pham, HSC; Jessica H. May, HSC

Community Reports are published by HSC:

President: Paul B. Ginsburg

Director of Site Visits: Cara S. Lesser

Editor: The Stein Group

For additional copies or to be added to the mailing list, contact HSC at:

600 Maryland Avenue SW, Suite 550, Washington, DC 20024-2512

Tel: (202) 554-7549 (for publication information)

Tel: (202) 484-5261 (for general HSC information)

Fax: (202) 484-9258

www.hschange.org