Issue Brief No. 95

May 2005

Marie C. Reed

More Americans—especially those with chronic conditions such as diabetes, asthma and depression—are going without prescription drugs because of cost concerns, according to a new national study by the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC). In 2003, more than 14 million American adults with chronic conditions—over half of whom were low income—could not afford all of their prescriptions. Between 2001 and 2003, the proportion of privately insured, working-age people with chronic conditions who reported not filling at least one prescription because of cost concerns increased from 12.7 percent to 15.2 percent. Likewise, the proportion of elderly, chronically ill Medicare beneficiaries without supplemental private insurance with problems affording prescription drugs rose from 12.4 percent to 16.4 percent between 2001 and 2003. At the same time, significant disparities in prescription drug access persisted between black and white Americans with chronic conditions, with blacks about twice as likely to report problems affording prescriptions.

![]() he proportion of American adults reporting problems affording

prescription drugs ticked up between 2001 and 2003, increasing from 12.0 percent

to 12.8 percent, according to HSC’s nationally representative Household Survey

(see Data Source). This small but statistically significant

increase in affordability problems likely resulted from higher prescribing rates

and increased patient cost sharing.

he proportion of American adults reporting problems affording

prescription drugs ticked up between 2001 and 2003, increasing from 12.0 percent

to 12.8 percent, according to HSC’s nationally representative Household Survey

(see Data Source). This small but statistically significant

increase in affordability problems likely resulted from higher prescribing rates

and increased patient cost sharing.

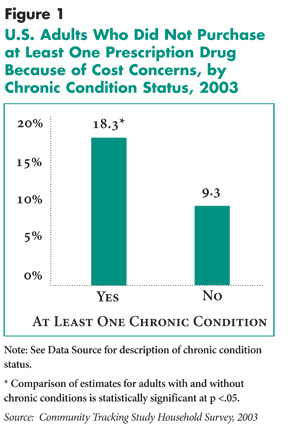

Among all adults, prescription drug access problems rose markedly for adults with chronic conditions,1 increasing from 16.5 percent in 2001 to 18.3 percent in 2003. However, access problems for adults without chronic conditions remained unchanged at about 9.2 percent during the same period. People with chronic conditions are more likely to need prescription drugs to manage their conditions, prevent complications and maintain quality of life. Partly because of higher prescription drug needs, adults living with chronic conditions in 2003 were twice as likely as those without chronic conditions to be unable to afford all of their prescription drugs (see Figure 1).

|

![]() etween 2001 and 2003, the proportion of privately insured

working-age adults (aged 18-64) with chronic health conditions who didn’t purchase

all of their prescriptions because of cost concerns increased from 12.7 percent

to 15.2 percent (see Table 1). In the past decade, prescription

drug utilization and spending in the United States increased dramatically. In

an effort to control rising prescription drug spending, health plans started

using formularies more aggressively and increasing patients’ out-ofpocket payment

requirements. These policies likely are a key reason for the increase in prescription

drug access problems for privately insured working-age Americans with chronic

conditions.

etween 2001 and 2003, the proportion of privately insured

working-age adults (aged 18-64) with chronic health conditions who didn’t purchase

all of their prescriptions because of cost concerns increased from 12.7 percent

to 15.2 percent (see Table 1). In the past decade, prescription

drug utilization and spending in the United States increased dramatically. In

an effort to control rising prescription drug spending, health plans started

using formularies more aggressively and increasing patients’ out-ofpocket payment

requirements. These policies likely are a key reason for the increase in prescription

drug access problems for privately insured working-age Americans with chronic

conditions.

Cost-related unmet prescription drug needs did not increase for working-age adults with chronic conditions who are uninsured or who are covered by public insurance, such as Medicaid. However, uninsured and publicly insured workingage adults with chronic conditions continue to have significantly higher rates of access problems than the privately insured. In 2003, one in two uninsured, nearly one in three publicly insured and one in six privately insured working-age adults with at least one chronic condition didn’t purchase all of their prescription drugs because of cost concerns.

While unmet needs for prescription drugs for privately insured people are relatively low, the privately insured constitute a sizeable segment of the overall population that reports problems affording prescription drugs. In 2003, 40 percent of adults with chronic conditions who reported prescription drug affordability problems were working age and privately insured—more than 5.5 million people.

Elderly Medicare beneficiaries living with chronic conditions who had private supplemental coverage—employer-sponsored or Medigap—were not more likely to report problems affording their prescriptions in 2003 than in 2001. But prescription drug access problems did increase for beneficiaries lacking supplemental private coverage, growing from 12.4 percent in 2001 to 16.4 percent in 2003. Many without private insurance did not have access to discounted prescription drug prices, a feature of many supplemental plans, and often had to pay list price.

Table 1

|

||

|

2001

|

2003

|

|

| Working-age Adults, 18-64 |

12.9%

|

13.6%

|

| No Chronic Condition |

9.6

|

9.5

|

| At Least One Chronic Condition |

20.0

|

22.2*

|

| Private Insurance |

12.7

|

15.2*

|

| Public Insurance |

31.3

|

32.3

|

| Uninsured |

51.7

|

50.8

|

| Elderly with Medicare |

7.7

|

8.9

|

| No Chronic Condition |

4.3

|

5.2

|

| At Least One Chronic Condition |

8.9

|

10.1

|

| Job-sponsored Supplemental |

3.4

|

3.2

|

| Other Private Supplemental |

10.0

|

9.0

|

| Other1 |

12.4

|

16.4*

|

| Note: See Data Source for description of chronic condition

status. 1 Includes Medcare fee-for-service, Medicare HMO and additional assistance through public programs such as Medicaid. * Comparison with 2001 is statistically significant at p <.05. Source: Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 2001 and 2003 |

||

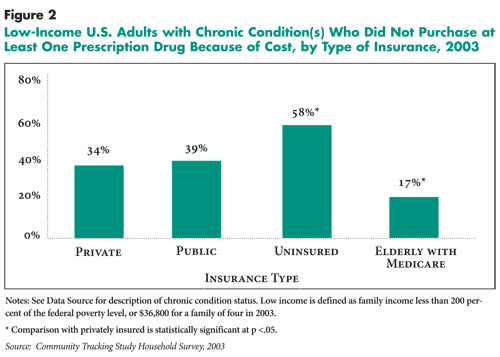

![]() egardless of insurance coverage, low-income

adults—those with incomes below

200 percent of the federal poverty level, or

$36,800 for a family of four in 2003—with

chronic conditions faced significant financial

barriers to obtaining prescribed drugs.

egardless of insurance coverage, low-income

adults—those with incomes below

200 percent of the federal poverty level, or

$36,800 for a family of four in 2003—with

chronic conditions faced significant financial

barriers to obtaining prescribed drugs.

Low-income, uninsured working-age adults with chronic conditions were most likely to have cost-related access problems, with nearly 60 percent reporting they could not afford all their prescriptions in 2003 (see Figure 2). Nearly 40 percent of chronically ill low-income people with public insurance, such as Medicaid, were unable to fill at least one prescription because of cost concerns. And, in 2003, the rate of access problems for low-income, privately insured working-age adults with chronic conditions was similar to that faced by those with public insurance—nearly 35 percent had costrelated unmet prescription drug needs. Among low-income elderly Medicare beneficiaries, 17 percent reported being unable to fill at least one prescription.

Many low-income people with chronic conditions who can’t afford prescription drugs face substantial medical bills. Regardless of insurance coverage, about half of low-income working-age adults with chronic conditions and an unmet prescription drug need paid more than 5 percent of their incomes for medical expenses in 2003 (see Table 2). And more than half of these—nearly 1.8 million working-age adults—paid more than 10 percent of their incomes for medical expenses and still were unable to purchase all of their prescriptions. These estimates are conservative since payments for insurance premiums were not included as out-of-pocket medical expenses.

Likewise, many older people are paying significant portions of their income for medical care and still can’t afford all of their prescriptions. In 2003, for example, 56 percent of the elderly with low incomes and chronic conditions who couldn’t afford all their prescriptions spent at least 5 percent of their income on medical care, and 37 percent paid more than 10 percent.

|

Table 2

|

||

|

Spent at Least 5 Percent of Income on Medical Expenses

|

Spent at Least 10 Percent of Income on Medical Expenses

|

|

| Working-age Adults, 18-64 |

49%

|

29%

|

| Private Insurance |

52

|

23

|

| Public Insurance |

53

|

35

|

| Uninsured |

42

|

27

|

| Elderly with Medicare |

56

|

37

|

| Note: See Data Source for description of

chronic condition status. Low income is defined as family income less than

200 percent of the federal poverty level, or $36,800 for a family of four

in 2003. Source: Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 2003 |

||

![]() rivately insured working-age blacks with chronic conditions

were nearly twice as likely as whites to not be able to afford all of their

prescriptions—22 percent vs. 13 percent—in 2003 (see Table

3). Similarly, 17 percent of black elderly Medicare beneficiaries reported

problems affording prescription drugs compared with 9 percent of white beneficiaries.

Between 2001 and 2003, cost-related prescription drug access disparities for

blacks compared with whites did not change (data not shown). Previous HSC research

2 found that, in 2001, working-age black Americans with private insurance

and elderly black Medicare beneficiaries were much more likely than comparable

white Americans to have costrelated unmet prescription drug needs and that these

disparities remained after adjusting for income and other socioeconomic factors.

rivately insured working-age blacks with chronic conditions

were nearly twice as likely as whites to not be able to afford all of their

prescriptions—22 percent vs. 13 percent—in 2003 (see Table

3). Similarly, 17 percent of black elderly Medicare beneficiaries reported

problems affording prescription drugs compared with 9 percent of white beneficiaries.

Between 2001 and 2003, cost-related prescription drug access disparities for

blacks compared with whites did not change (data not shown). Previous HSC research

2 found that, in 2001, working-age black Americans with private insurance

and elderly black Medicare beneficiaries were much more likely than comparable

white Americans to have costrelated unmet prescription drug needs and that these

disparities remained after adjusting for income and other socioeconomic factors.

This type of racial disparity does not exist to a significant extent between uninsured or publicly insured blacks and whites with chronic conditions—their prescription access problems are high regardless of race. For example, nearly one in three working- age chronically ill whites and blacks with public insurance reported not being able to afford a prescription drug, while 53 percent of uninsured whites and 60 percent of uninsured blacks couldn’t afford to fill a prescription.

African-Americans are more likely to have certain chronic conditions, such as hypertension and diabetes, than whites. This double jeopardy—a combination of higher disease rates and greater inability to afford all prescriptions—results in much higher overall risk for blacks compared with whites. For example, 7 percent of all working-age black Americans had hypertension in 2003 and were unable to purchase all of their prescriptions because of cost concerns—nearly three times the rate for working-age whites.

Table 3

|

||

|

Non-Hispanic Whites

|

Non-Hispanic

Blacks |

|

| Working-age Adults, 18-64 |

20%

|

30%*

|

| Private Insurance |

13

|

22*

|

| Public Insurance |

32

|

32

|

| Uninsured |

53

|

60

|

| Elderly with Medicare |

9

|

17*

|

| Note: See Data Source for description of

chronic condition status. * Comparison with whites is statistically significant at p <.05. Source: Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 2003 |

||

![]() ore than 14 million American adults of

all ages with chronic conditions—more

than half with low incomes—could not

afford all of their prescriptions in 2003.

One-fifth of adults with chronic conditions

who had cost-related unmet prescription

drug needs in 2003 were elderly, one-fifth were uninsured, a fifth had public insurance,

such as Medicaid, and two-fifths were

privately insured.

ore than 14 million American adults of

all ages with chronic conditions—more

than half with low incomes—could not

afford all of their prescriptions in 2003.

One-fifth of adults with chronic conditions

who had cost-related unmet prescription

drug needs in 2003 were elderly, one-fifth were uninsured, a fifth had public insurance,

such as Medicaid, and two-fifths were

privately insured.

Many older people will be helped by the Medicare prescription drug benefit that goes into effect in 2006, but other significant segments of the American public also are unable to afford all of their prescriptions. Some of the uninsured may be helped by private drug discount plans. For example, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recently announced the Together Rx Access Card, a prescription drug discount plan sponsored by 10 pharmaceutical companies that may help uninsured persons save up to 40 percent on some prescriptions. While this effort is likely to increase the affordability of prescription drugs for many people, some uninsured people, especially those with low incomes, would still face significant out-ofpocket costs for prescription drugs.

As states wrestle with budget problems, Americans who rely on Medicaid for access to prescription drugs are likely to experience more affordability problems. Many states are instituting additional cost-containment policies to control the growth of prescription drug spending, including limiting the number of allowable prescriptions and requiring patients to pay a portion of the cost.

Since 2002, employers and private health plans have shifted costs to workers through increased patient cost sharing, especially for prescription drugs. This trend continued in 2003 and 2004, and it is unclear where employers will draw the line on increased patient cost sharing.

As medical needs for prescription drugs continue to grow, it’s likely that the proportion of working-age Americans, especially those with chronic conditions, going without prescription drugs because of cost concerns will continue to grow.

| 1. | To determine whether people had chronic conditions, the survey asked adult respondents whether they had been diagnosed with one of more than 10 chronic conditions and whether they had seen a doctor in the past two years for the condition. The list of chronic conditions includes asthma, arthritis, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart disease, hypertension, cancer, benign prostate enlargement, abnormal uterine bleeding and depression. The CTS list is not exhaustive but does include the most prevalent chronic conditions faced by American adults. |

| 2. | Reed, Marie C., and J. Lee Hargraves, Prescription Drug Access Disparities Among Working-Age Americans, Issue Brief No. 73, Center for Studying Health System Change, Washington, D.C. (December 2003). See also, Reed, Marie C., J. Lee Hargraves, and Alwyn Cassil, Unequal Access: African- American Medicare Beneficiaries and the Prescription Drug Gap, Issue Brief No. 64, Center for Studying Health System Change, Washington, D.C. (July 2003). |

This Issue Brief presents findings from the 2001 and 2003 HSC Community Tracking Study (CTS) Household Survey, a nationally representative telephone survey of the civilian, noninstitutionalized population. The 2001 survey, which had a response rate of 59 percent, contains information from more than 46,400 persons 18 years or older. The 2003 survey, with a 57 percent response rate, includes data from more than 36,500 adults. Estimates in this Issue Brief reflect the percentage of adults who responded “yes” to the following question: “During the past following question: “During the past 12 months, was there any time you needed prescription medicines but didn’t get them because you couldn’t afford it?”

To determine whether people had chronic conditions, the survey asked adult respondents whether they had been diagnosed with one of more than 10 chronic conditions and whether they had seen a doctor in the past two years for the condition. The list of chronic conditions includes asthma, arthritis, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart disease, hypertension, cancer, benign prostate enlargement, abnormal uterine bleeding and depression. The CTS list is not exhaustive but does include the most prevalent chronic conditions faced by American adults.

ISSUE BRIEFS are published by the

Center for Studying Health System Change.

600 Maryland Avenue, SW, Suite 550

Washington, DC 20024-2512

Tel: (202) 484-5261

Fax: (202) 484-9258

www.hschange.org