Congressional Testimony

July 18, 2006

Statement of Ha T. Tu, M.P.A., Senior Health Researcher

Center for Studying Health System Change

Before the U.S. House of Representatives

Committee on Ways and Means

Subcommittee on Health

Hearing on Price Transparency in the Health Care Sector

Madame Chairman, Representative Stark and members of the Subcommittee, thank you for the invitation to testify. My name is Ha T. Tu, and I am a senior health researcher at the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC). HSC is an independent, nonpartisan health policy research organization funded principally by The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and affiliated with Mathematica Policy Research.

HSC’s main research tool is the Community Tracking Study, which consists of national surveys of households and physicians in 60 nationally representatives communities across the country and intensive site visits to 12 of these communities. We also monitor secondary data and general health system trends. Our goal is to provide members of Congress and other policy makers with high-quality, objective and timely research on developments in health care markets and their impact on people. Our various research and communication activities may be found on our Web site at www.hschange.org.

With funding from the California HealthCare Foundation, HSC has conducted research on consumer price shopping for health services, focusing both on self-pay services, such as LASIK, and analyzing the issue of price transparency for medical services that tend to be insured.1

My testimony today will focus on three key points:

SELF-PAY MARKETS

Whether they belong to conventional health plans with rising cost-sharing requirements or enroll in consumer-driven health plans with high deductibles and a spending account, consumers are facing more incentives to make cost-conscious decisions about medical services. Consumer-oriented approaches to health care emphasize price shopping as a tool for individual consumers to obtain better value and for the health system as a whole to curb rising costs and improve quality through increased competition. Until recently, most insured consumers have been sheltered from rising health care costs and have had few incentives to shop for the best deal. The extent to which consumers actually can become effective shoppers in the health care marketplace remains largely unexplored.

Self-pay markets in health care—those markets in which consumers largely pay out of pocket for services because of little or no insurance coverage—provide insights into how markets work when consumers must pay the total costs of services without the benefit of discounted rates negotiated by health plans or the restrictions of a provider network chosen by insuers.

Our research examines several self-pay markets in health care, focusing on one in particular-laser assisted in-situ keratomileusis (LASIK), a type of vision-correction surgery. LASIK was chosen for in-depth analysis largely because it is widely regarded as the self-pay market with the most favorable conditions for consumer shopping: it is an elective, non-urgent, simple procedure, giving consumers time and ability to shop; screening exams are not required to obtain initial price quotes, keeping the dollar and time costs of shopping reasonable; and easy entry of providers (ophthalmologists) into the market has stimulated competition and kept prices down.

While LASIK is a good procedure to evaluate for price shopping for these reasons, it is important to note that patients are rarely in a position to shop for completely elective, non-time-sensitive procedures, even if good price and quality information were available.

In addition to the in-depth look at LASIK, we’ve also examined other self-pay markets—in vitro fertilization (IVF), cosmetic rhinoplasty and dental crowns—to highlight how additional complexities and barriers to price and quality transparency affect consumer shopping behavior.

LASIK

Study Methodology. Initial research included a review of existing literature and news stories; informational material published by professional associations and government regulators; and industry consultants’ market reports. In addition, researchers reviewed online patient forums and examined LASIK providers’ Web sites and print advertisements. Interviews included LASIK providers, industry consultants, laser equipment manufacturers, government regulators, and professional associations’ management and senior staffs. Respondents were asked about the overall nature of the LASIK market—for example, to discuss price and quality information available to consumers and to describe typical consumer shopping behavior. Respondents also were asked specific questions based on their expertise and position in the market—for example, industry consultants discussed overall market trends and government regulators discussed misleading advertising and regulatory oversight of LASIK. In addition, the industry’s professional association and a consulting company that specializes in providing LASIK price and volume data provided supplementary data on the LASIK market.

The Procedure. LASIK is an outpatient surgical procedure performed by an ophthalmologist that permanently reshapes corneal tissue to reduce light-refraction error and improve vision. A surgical blade creates a flap in the outer layer of the cornea. After the flap is folded back, a laser is used to reshape the underlying corneal tissue, and the flap is replaced. The surgery takes 10-15 minutes per eye, and the only anesthetic is an eye drop that numbs the eye’s surface. LASIK was first performed in the United States in clinical trials in 1995.

Complications of LASIK include infection, dry eye, the flap failing to adhere correctly after surgery, less-than-perfect vision correction, and visual disturbances, such as seeing glare and halos, especially at night. Experts estimate that complications occur in 5 to 7 percent of all procedures. The complication rate has decreased over time with greater surgical experience and technological advances. The rate of severe complications, such as those that threaten long-term vision, is estimated to be less than .01 percent. In 5 to 18 percent of procedures, a second operation—called enhancement surgery—is needed to correct refractive error that was either not corrected in the first procedure or caused by the first procedure. The higher a patient’s refractive error to start with, the greater the likelihood that enhancement surgery will be needed.

In the past few years, two new technologies have emerged in the LASIK industry. The first, custom wavefront-guided LASIK, uses wavefront technology to measure precisely how each eye refracts light and then guide the laser in customizing the corneal reshaping. Unlike conventional LASIK, custom LASIK can treat higher-order aberrations and is more likely to produce 20/20 or better vision and is less likely to result in visual distortions. Providers have widely adopted custom LASIK: 80 percent of providers now offer this technology, and the procedure accounted for nearly half of all LASIK procedures in 2005, according to MarketScope, LLC data.

The second refinement, blade-free or all-laser LASIK, involves the use of a laser instead of a surgical blade to create the corneal flap and is usually referred to as IntraLase. Many surgeons believe that IntraLase creates a more precise flap and results in fewer complications. Compared to custom LASIK, however, IntraLase market penetration has not been nearly as high: The technology was used in one in 10 LASIK procedures in 2005, according to MarketScope, LLC data.

Market Structure and Pricing. Market insiders describe the LASIK market as having three pricing tiers: discount, mid-priced and premium-priced providers. Discounters tend to market aggressively based on price. They typically handle a high volume of procedures, and patients often have little or no contact with the surgeon before or after surgery.

While discount providers are almost always high volume, experts note higher pricing does not necessarily equate to lower volume. What all premium providers tend to have in common is that they are surgeons whose credentials (such as research publications, affiliations with teaching hospitals and participation in clinical trials) enable them to command top dollar. Beyond this common trait, however, it is harder to generalize about these practices. Many premium providers run relatively low-volume LASIK practices that offer patients personalized care from the surgeon, both before and after surgery. Other premium-priced providers operate on a different business model: marketing themselves heavily, performing high volumes of LASIK procedures, and often relying on optometrists to conduct pre- and post-operative exams.

Many mid-priced providers are somewhat like the premium providers but without the top-notch credentials or surgical experience to command higher prices. Other mid-priced providers are large chains that may have started out as discount providers but moved to the mid-price segment through an emphasis on customer service, celebrity endorsements or other means.

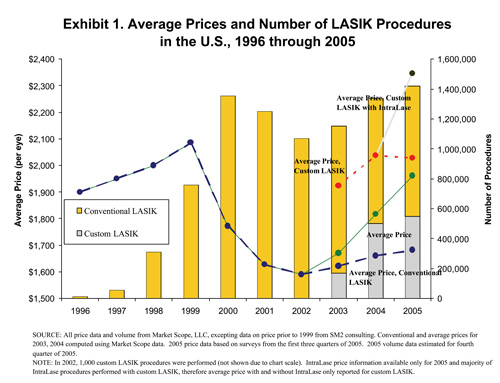

In 2005 the price of LASIK averaged approximately $1,680 per eye for the conventional procedure and $2,030 for the custom procedure (see Exhibit 1). Premium-priced providers currently charge about $2,200 per eye for conventional LASIK and $2,700-$2,800 for the most advanced technology (custom LASIK with IntraLase).

Although discount providers often advertise that LASIK is available for only a few hundred dollars, market experts note that the actual price of LASIK from a discounter averages $1,100-$1,200 per eye for the conventional procedure and $1,500-$1,600 per eye for custom LASIK, both with a surgical blade. (Most discounters have yet to adopt IntraLase technology.) This substantial discrepancy between actual and advertised prices exists largely because very few LASIK patients are medically eligible for the lowest prices. Indeed, it has been estimated that only 3 percent of LASIK procedures are performed for less than $1,000 per eye.2

In the decade that LASIK has been performed in the U.S., price and volume have fluctuated somewhat, but overall the average price for conventional LASIK has declined nearly 30 percent in inflation-adjusted terms. Two factors appear to be largely responsible for this market’s price competitiveness: on the provider side, a large number of providers (ophthalmologists) can enter the market relatively easily; and on the consumer side, price quotes can be obtained at little cost and inconvenience. However, the decline in LASIK price is much less steep than what a casual observer might infer, given the pervasive advertisements of LASIK for only a few hundred dollars per eye.

There is no consistent bundling of LASIK services across providers. A high-end LASIK surgeon’s fee might include a thorough screening exam, the procedure itself, and several post-operative exams, all conducted by the surgeon. If enhancement surgery is needed, a premium-priced surgeon might charge the patient nothing at all or only the procedure fee charged by the laser manufacturer. At the other extreme, some discount providers charge patients a nonrefundable fee for the screening exam, include little post-operative care and require full payment for enhancement surgery.

Information Available to Consumers. Reliable consumer information about LASIK is available from several sources, including the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO), which jointly produced a free consumer brochure, Basik Lasik.3 This consumer resource discusses the procedure, its risks and possible complications; how to locate a surgeon; and what to expect before, during and after surgery. To help consumers find a surgeon, the AAO Web site lists all AAO members performing refractive surgery.

Basik Lasik and similar sources provide guidance to consumers on questions to ask of surgeons, but consumers still must gather this information from each provider. No centralized source is available for information such as number of procedures performed, success rates or enhancement rates for each surgeon, so consumers seeking to compare such quality-related measures across providers must invest considerable effort to gather this information.

Consumer Shopping Behavior. Although LASIK consumers are a heterogeneous group, the majority shares one trait, according to industry experts: Word-of-mouth recommendation from a previous LASIK patient is the most common way to select a LASIK surgeon. This holds true for all market segments, from discount to premium-priced providers. Practices that advertise heavily do draw many new patients through marketing efforts, but word-of-mouth still plays an important role-accounting for perhaps half of most discount providers’ LASIK customers, according to industry observers. 4

According to premium-priced surgeons, well over half of their patients tend to be focused on quality considerations. These patients are likely to ask prospective providers about LASIK technology, safety and outcomes, and a subset of these patients has done extensive research before contacting a provider. Among discount practices, not surprisingly, price tends to be the most important priority, and patients are much less inclined to focus on quality or to have done research. Industry experts estimate that perhaps one in five LASIK consumers overall—and a much larger proportion of discount providers’ customers—tend to shop intensively for the lowest price (often by telephone) and base their purchasing decision solely on price.

In the LASIK market—in contrast to other self-pay markets—it is possible for a consumer to obtain telephone price quotes if they have their vision prescription.5 An in-person exam is still needed, however, before the provider can assess the patient’s eligibility for surgery, the likelihood of complications and the potential benefits of custom LASIK over conventional LASIK.

Consumer Satisfaction. Satisfaction rates among LASIK patients are high—about 90 percent industry-wide. Among premium-priced practices, especially those that emphasize careful screening and patient preparation, satisfaction rates can reach the high 90s. Even among high-volume discounters, some of which have received negative publicity for questionable business practices and some bad outcomes, satisfaction rates still appear to range in the 80s.

Issues Facing LASIK Consumers

Lack of Consistent Bundling. Because the package of services that are included in LASIK procedure fees varies across providers, consumers shopping in this market are confronted with "apples vs. oranges" comparisons. One critical factor when comparing providers’ fees is to consider whether the provider includes the cost of enhancement surgery in the quote. A price quote that appears to be the best deal but does not cover follow-up operations may end up being the highest-cost option if enhancement surgery is needed. Whether thorough screening exams are included and how much post-operative care is included in the procedure fee also varies.

Misleading Advertising. Misleading advertisements have been a recurring problem with some LASIK providers, most notably discounters; federal and state regulators have taken action against some providers—and investigated many more—for making claims about price and quality that were found to be unwarranted.

In 2003, for instance, the FTC issued a consent order against LASIK Vision Institute (LVI) after finding that the national chain falsely claimed that consumers would receive a free consultation to determine their LASIK eligibility. Instead, consumers, after an initial meeting with a salesperson, were required to pay a $300 deposit before they could meet with an optometrist to be told of risks, possible complications and medical eligibility. If the consumer decided not to proceed with surgery, the entire deposit was nonrefundable. If the consumer chose to undergo surgery but was rejected for medical reasons, only a portion of the deposit was refunded. Although LVI signed an FTC consent decree, the practice of advertising but not providing a free screening has persisted in some markets. In November 2005, the Illinois Attorney General took action against LVI for this same violation, along with other misleading practices.

Advertisements run by discount providers touting very low LASIK prices are another important source of consumer misinformation. LVI, for example, runs advertisements promising "LASIK for $299." On LVI’s Web site, the fine print states the offer is for surgery on one eye and applies only to those with no astigmatism and very low myopia, conditions that apply to a small portion of the LASIK patient base. Similar problems have occurred with print advertisements, leading at least two state attorneys general, in Illinois and Florida, to take action against LVI in 2005.

Consumers can be misled on quality issues as well by some advertisements. The 2003 FTC consent decree against LVI cited the provider for making unsubstantiated claims that LASIK would eliminate the need for glasses and contact lenses for life. Another national provider, LasikPlus, also was cited for making this claim, as well as additional unfounded claims that the procedure posed less risk to patients’ eyes health than wearing glasses or contacts and that the procedure carried no risk of side effects.

In many cases questionable practices have persisted despite the settlements. And, regulators note that for the FTC to take official enforcement action against a provider, a practice must be "egregious" and "widespread;" they concede that consumers can also be misled by many questionable practices that fall short of these criteria. For example, local LASIK providers engaging in some of the same advertising practices as LVI would not be targets of FTC action, since their practices are not national in scope. Policing such providers generally would be left to state and local regulators, which vary greatly in the extent to which they enforce consumer protection.

Quality Issues. Many industry observers express concern that LASIK is regarded as a commodity by some consumers—leading them to shop only on price—when provider quality, in their opinion, varies considerably. Quality differences may be obscured by the fact that LASIK is relatively simple surgery with low complication rates, but for patients whose eyes have certain "problem" characteristics (e.g., abnormal topography, large pupils, thin corneas), quality differences may be critical.

Screening is the first step where provider quality differences matter: Industry insiders note that some providers—especially high-volume discount providers-may not adequately screen out patients who are not good LASIK candidates. When such patients are accepted for surgery, whether through revenue pressures or less-experienced or skilled screening staff, they suffer serious complications at much higher rates than average.

Investments in technology are another area where providers differ: The lower the price charged by providers, the less likely they are to use state-of-the-art technology that may provide better results. According to experts, the very low prices quoted by discount providers assume the use of older, less expensive laser technology that may produce an acceptable result (for example, 20/40 vision with visual aberrations) when a newer, more expensive technology might have produced a better outcome (better than 20/20 vision with no aberrations).

Poor quality outcomes, including severe pain, loss of best-corrected vision, or persistent double vision have been well documented in media accounts, online health forums and other sources. Such outcomes can result not only from poor screening but also from inadequate skill or experience from the surgeon, providing further evidence that LASIK is not a commodity and that quality differences can be substantial across providers.

Other Self-Pay Markets

While I have focused on the LASIK market, as I mentioned earlier, we also looked at self-pay markets for in vitro fertilization (IVF), cosmetic rhinoplasty and dental crowns. Consumers engage in little price shopping for IVF, rhinoplasty and dental crown services, according to experts in these markets. For IVF and rhinoplasty, most consumers choose providers based on previous patients’ recommendations or physician referrals. For dental crowns, virtually all patients choose to stay with their regular dentist rather than shop around.

One important reason why shopping takes place so infrequently for these procedures is that accurate price quotes can only be obtained after undergoing in-person screening exams, since costs vary according to patient characteristics and medical needs as assessed by each provider. In some markets (cosmetic surgery) it is customary for some providers to offer free screenings, while in other markets (IVF and dental procedures), providers always charge for the exam. In the latter case, any potential benefit of identifying a low-cost provider would likely be negated by the costs of obtaining price quotes. But even when screenings are provided free of charge, consumers must still invest considerable effort in gathering price quotes.

Urgency is another factor precluding some consumers from shopping for IVF and dental crown services. Since one of the indications for a crown is that a portion of a tooth is missing, some patients may be in pain while shopping. Although IVF treatment may not qualify as medically urgent, industry experts note that consumers’ sense of urgency about starting the procedure makes them unlikely to spend time price-shopping.

In the dental crown market, there are also important psychological barriers to shopping around. Surveys suggest that a large majority of consumers trust their own dentists, but at the same time, many express some fear or anxiety about major dental procedures. Thus, most consumers, when faced with the prospect of undergoing a major dental procedure, would be highly unlikely to switch from a regular provider they already know and trust to an unknown dentist solely to save on costs.

Implications for Price Shopping

Consumer-oriented approaches to health care sometimes focus on price shopping, without giving adequate priority to comparing quality across providers. Yet, widespread reliance on word-of-mouth recommendation in self-pay markets suggests that many consumers place a high priority on quality but may be using referrals from physicians or previous patients as a proxy for quality, given the absence of or shortcomings in concrete quality measures.

Concerns about quality disparities across providers appear to be warranted: Even for the relatively simple LASIK procedure—sometimes considered a commodity—quality differences across providers can be marked and can prove critical, particularly for the significant minority of consumers who have "problem" characteristics that put them at greater risk for complications or unsatisfactory outcomes. Consumers who consider only price when shopping for LASIK may end up with providers they would not have chosen if they had been aware of quality disparity issues. These consumers may not receive the best value for their money, even if they obtained the lowest price.

For consumers who do take quality into account when shopping, comparing quality across providers can be challenging. For LASIK, consumers must gather data on success and re-operation rates from individual providers. Along with a need for centralized quality information, there is also a need to adjust outcomes data for patient mix—something not yet available in any of the self-pay markets we examined.

Educating consumers—providing information such as what credentials to look for in providers, how to compare prices and quality across providers, and what misleading claims to look out for—is essential if consumers are to act as their own agents in the marketplace. Government and professional associations can jointly take on consumer education, as they have done in the LASIK market. Monitoring of and enforcement against providers who engage in misleading advertising are also key elements of consumer protection. As the number and complexity of health care markets in which consumers are expected to shop on their own behalf expand, resources devoted to consumer protection will need to be increased substantially.

If all the tools discussed here were implemented, many consumers would benefit from improved price and quality transparency, but the benefits would not accrue to all consumers equally. Previous research has found that consumers with more education are much more inclined to seek health information on their own behalf,6 so they are the most likely to benefit directly from any measures that improve price and quality transparency.

In applying lessons learned from self-pay markets to services covered by health insurance, it should be noted that many covered services are more urgent and more complex than the procedures we have analyzed-factors that would greatly reduce consumer inclination and ability to comparison shop. In addition, the fact that insurance will cover part of the cost reduces the financial incentive for the consumer to shop vigorously. Given that consumer shopping is not prevalent or active in most self-pay markets, we would expect the extent of shopping to be even more limited for many insured services.

ROLE OF INSURERS IN PRICE TRANSPARENCY

Moving from self-pay markets where consumers are responsible for paying the total bill to covered health care services, where consumers have less of a financial stake in care decisions, it’s important to keep in mind the role of insurers. Much of the policy discussion about price transparency has neglected the important role that insurers play as agents for consumers and purchasers of health insurance in obtaining favorable prices from providers, as HSC President Paul B. Ginsburg, Ph.D., testified earlier this year before Congress.7 Even though insurers have lost some clout in negotiating with providers in recent years, they still obtain sharply discounted prices from contracted providers.

Insurers are in a strong position to further support their enrollees who have significant financial incentives, especially those in consumer-driven products. Insurers have the ability to analyze complex data and present it to consumers as simple choices. For example, they can analyze data on costs and quality of care in a specialty and then offer their enrollees an incentive to choose providers in the high-performance network. Insurers also have the potential to innovate in benefit design to further support effective shopping by consumers, such as increasing cost sharing for services that are more discretionary and reducing cost sharing for services that research shows are highly effective.

Insurers certainly are motivated to support effective price shopping by their enrollees. Employers who are moving cautiously to offer consumer-driven plans want to choose products that offer useful tools to inform enrollees about provider price and quality. When enrollees become more sensitive to price differences among providers, this increases health plan bargaining power with providers. Negotiating lower rates further improves a health plan’s competitive position. One thing that insurers could do that they are not doing today is to assist enrollees in making choices between network providers and those outside of the network by providing data on likely out-of-pocket costs for using non-network providers.

PRICE TRANSPARENCY CAN LEAD TO HIGHER PRICES IN SOME CASES

The Administration has recently been pushing hospitals and physicians to provide more information on prices to the public. If this is limited to prices paid by those who are not insured or those who are insured but are opting to use a non-network provider, additional price information for the public is may be a positive. But if hospitals and insurers are precluded from continuing their current practice of keeping their contracts confidential, this could damage the interests of those who pay for services, especially hospital care.

Antitrust authorities throughout the world have recognized that posting of contracted prices tends to lead to higher prices. In highly concentrated markets, posting of prices facilitates collusion. Even in the absence of collusion, posting would mean that a hospital offering an extra discount to an insurer would gain less market share because their competitors would seek to match it. Of course, this works on both the buying and selling side of the market, but if hospitals tend to be more concentrated than insurers, disclosure will raise rather than lower prices.

The experience in Denmark, where the government, in a misguided attempt to foster more competition in a concentrated market, posted contracted prices in the ready-mix concrete industry is instructive. Within six months of this policy change, prices increased by 15-20 percent, despite falling input prices.8

POTENTIAL FOR MORE EFFECTIVE PRICE SHOPPING

Unfortunately, much of the recent policy discussion about price transparency downplays the complexity of decisions about medical care and the dependence of consumers on physicians for guidance about what services are appropriate. It also ignores the role of health insurers as agents for consumers and purchasers in shopping for lower prices. Well-intentioned but ill-conceived policies to force extensive disclosure of contracts between managed care plans and providers may backfire by leading to higher prices.

We need to be realistic about the magnitudes of potential gains from more effective shopping by consumers. For one thing, a large portion of medical care may be beyond the reach of patient financial incentives. Most patients who are hospitalized will not be subject to the financial incentives of either a consumer-driven health plan or a more traditional plan with extensive patient cost sharing. They will have exceeded their annual deductible and often their maximum on out-of-pocket spending. Recall that in any year, 10 percent of people account for 70 percent of health spending.

When services are covered by health insurance, the value of price information to consumers depends a great deal on the type of benefit structure. For example, if the consumer has to pay $15 for a physician visit or $100 per day in the hospital, then information on the price for these services is not relevant. If the consumer pays 20 percent of the bill, price information is more relevant, but still the consumer gets only 20 percent of any savings from using lower-priced providers. And the savings to the consumer end once limits on out-of-pocket spending are reached.

In addition to those with the largest expenses not being subject to financial incentives, much care does not lend itself to effective shopping. Many patients’ health care needs are too urgent to price shop. Some illnesses are so complex that significant diagnostic resources are needed before determining treatment alternatives. By this time, the patient is unlikely to consider shopping for a different provider.

Some of these constraints could be addressed by consumers’ committing themselves, either formally or informally, to providers. Many consumers have chosen a primary care physician as their initial point of contact for medical problems that may arise, and choice of physician often drives choice of hospitals. Patients served by a multi-specialty group practice informally commit themselves to this group of specialists—and the hospitals that they practice in—as well. So shopping has been done in advance and can be applied to new medical problems that require urgent care. This is a key concept behind the high-performance networks that are being developed by some large insurers.

CONCLUSION

The need for consumers to compare prices of providers and treatment alternatives

is increasing and has the potential to improve the value equation in health

care. But we need to be realistic about the magnitude of the potential for improvement

if consumers become more effective shoppers for health care.