Data Bulletin No. 34

September 2007

Catherine Corey, Joy M. Grossman

![]() hile practice setting and size are the strongest predictors

of physicians’ access to clinical information technology (IT) in their practices,1

significant variation in IT adoption exists across specialties, according to

findings from HSC’s nationally representative 2004-05 Community Tracking Study

(CTS) Physician Survey. Clinical IT can potentially improve coordination of

care between primary care physicians (PCPs) and other specialists and support

quality improvement and reporting activities, but certain specialties lagging

in adoption can reduce the effectiveness of these activities.

hile practice setting and size are the strongest predictors

of physicians’ access to clinical information technology (IT) in their practices,1

significant variation in IT adoption exists across specialties, according to

findings from HSC’s nationally representative 2004-05 Community Tracking Study

(CTS) Physician Survey. Clinical IT can potentially improve coordination of

care between primary care physicians (PCPs) and other specialists and support

quality improvement and reporting activities, but certain specialties lagging

in adoption can reduce the effectiveness of these activities.

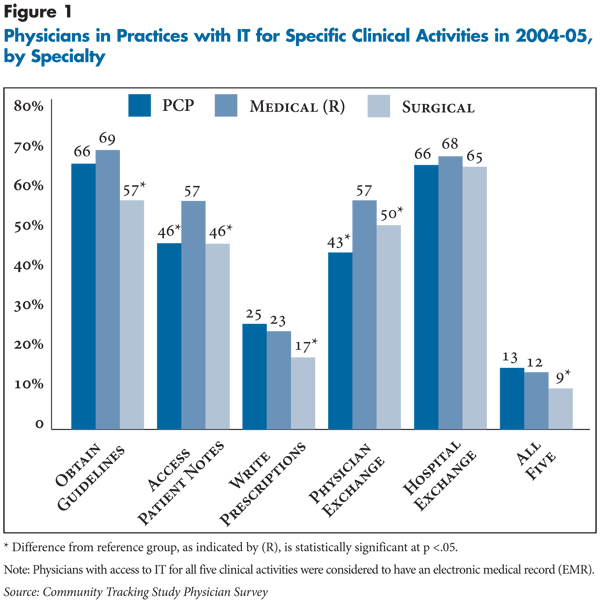

The CTS survey asked physicians about the availability of IT in their practice for five clinical activities, rather than about the use of specific technologies.2 The five activities are as follows: Obtaining information about treatment alternatives or recommended guidelines; accessing patient notes, medication lists or problem lists; writing prescriptions; exchanging clinical data and images with other physicians; and exchanging clinical data and images with hospitals. Physicians with access to IT for all five clinical activities were considered to have an electronic medical record (EMR).

Across primary care, medical and surgical specialties, significant variation in access to IT exists. Surgeons lagged medical specialists in access to IT for four of the five clinical activities and also were less likely to have all five clinical activities associated with an EMR (see Figure 1). PCPs lagged medical specialists in IT access for two activities, accessing notes and exchanging data with physicians.

![]() ifferences in IT access among subspecialties were even

greater, particularly for medical subspecialists (see Table

1). Psychiatrists were substantially less likely than the comparison group

of other medical subspecialists to access IT for all activities, except writing

prescriptions. In contrast, oncologists were much more likely than the comparison

group to have access to IT for guidelines and exchanging data with hospitals

and physicians.

ifferences in IT access among subspecialties were even

greater, particularly for medical subspecialists (see Table

1). Psychiatrists were substantially less likely than the comparison group

of other medical subspecialists to access IT for all activities, except writing

prescriptions. In contrast, oncologists were much more likely than the comparison

group to have access to IT for guidelines and exchanging data with hospitals

and physicians.

Among surgical subspecialties, ophthalmologists lagged the comparison group of general and other surgical subspecialties for all measures but obtaining guidelines. Obstetricians/gynecologists (OB/GYNs) were less likely than the comparison group to access notes and exchange data with physicians or hospitals.

Among primary care subspecialties, the major difference was that pediatricians and general and family physicians were less likely than internists to access IT for patient notes.

Table 1

|

|||||||

|

Obtain Guidelines

|

Access Patient Notes

|

Write Rx

|

Physician Exchange

|

Hospital Exchange

|

All Five

|

||

| All Physicians |

65%

|

50%

|

22%

|

50%

|

66%

|

12%

|

|

| Primary Care | |||||||

| General/Family Practice |

65

|

45*

|

27

|

42

|

62*

|

14

|

|

| Pediatrics |

70

|

40*

|

21

|

47

|

66

|

11

|

|

| Internal Medicine (R) |

66

|

53

|

24

|

42

|

71

|

15

|

|

| Medical Specialty | |||||||

| Cardiology |

64

|

69*

|

25

|

47

|

75

|

13

|

|

| Emergency Medicine1 |

73

|

74*

|

33*

|

70*

|

83*

|

15

|

|

| Oncology |

86*

|

61

|

23

|

85*

|

93*

|

18

|

|

| Psychiatry |

52*

|

36*

|

20

|

34*

|

34*

|

6*

|

|

| Other Medical (R) |

73

|

55

|

19

|

58

|

70

|

12

|

|

| Surgical Specialty | |||||||

| Ob/Gyn |

59

|

34*

|

20

|

32*

|

60*

|

11

|

|

| Ophthalmology |

64

|

23*

|

9*

|

43*

|

45*

|

2*

|

|

| Orthopedics |

38*

|

56

|

17

|

56

|

67

|

8

|

|

| General and Other Surgical (R) |

60

|

56

|

17

|

62

|

73

|

11

|

|

| 1 Emergency medicine physicians’ responses

may reflect access to clinical IT in the hospital emergency departments

where they most commonly see patients, rather than in an office setting. * Difference from reference group, as indicated by (R), is statistically significant at p <.05. Note: Physicians with access to IT for all five clinical activities were considered to have an electronic medical record (EMR). Source: Community Tracking Study Physician Survey |

|||||||

![]() ariation in access to IT by subspecialty persisted even

after accounting for differences in practice setting/size, the major driver

of IT adoption. Variation in IT by both practice setting/size and specialty

might be partly explained by differences in practice financial resources to

invest in IT. Two indirect measures of financial resources—physician income

and the percent of practice revenue from Medicaid—were not generally associated

with reported access to IT (data not shown).

ariation in access to IT by subspecialty persisted even

after accounting for differences in practice setting/size, the major driver

of IT adoption. Variation in IT by both practice setting/size and specialty

might be partly explained by differences in practice financial resources to

invest in IT. Two indirect measures of financial resources—physician income

and the percent of practice revenue from Medicaid—were not generally associated

with reported access to IT (data not shown).

While practice setting/size and financial resources dominate the decision to implement IT, specialty may affect IT adoption in a number of ways. Patterns of specialty adoption may reflect the relevance of particular clinical activities. For example, clinical data exchange with hospitals is highly relevant to patient care for general surgeons, while it may be less relevant for ophthalmologists, who often perform procedures in ambulatory surgery centers or office-based settings. Surgeons may have less need for IT to write prescriptions since they typically prescribe a narrow range of on-formulary medications on a short-term basis in contrast to medical specialists and PCPs who treat chronically ill patients taking multiple medications.

In other cases, existing EMR products may not meet the distinct clinical needs of some specialties, such as enhanced drawing features and imaging storage for ophthalmologists monitoring glaucoma patients or growth tracking capabilities and pediatric dosing calculations for pediatricians. Supporting this explanation, 81 percent of pediatricians without EMRs surveyed in 2005, reported that the inability to find an EMR that met pediatric-specific requirements was a barrier to adoption.3

| 1. | Grossman, Joy M. and Marie C. Reed, Clinical Information Technology Gaps Persist Among Physicians, Issue Brief No. 106, Center for Studying Health System Change, Washington, D.C. (November 2006); and Blumenthal, David, et al., Health Information Technology in the United States: The Information Base for Progress, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Princeton, New Jersey (2006). |

| 2. | For example, physicians can access electronic patient notes through a variety of mechanisms, such as an electronic medical record (EMR), practice management system, or Web-based portal. And a given application, such as an EMR, can support some or all of the clinical activities. Because physicians were asked about IT availability in their practice but not whether they actually use the technology or the frequency or intensity of use, the estimates presented here should be considered an upper bound on the proportion of physicians regularly using clinical IT in their practices. |

| 3. | Kemper, Alex R., et al., “Adoption of Electronic Health Records in Primary Care Pediatric Practices,” Pediatrics, Vol. 118, No. 1, (July 2006). |

This Data Bulletin presents findings from the HSC Community Tracking Study Physician Survey, a nationally representative telephone survey of physicians involved in direct patient care in the continental United States conducted in 1996-97, 1998-99, 2000-01 and 2004-05. The sample of physicians was drawn from the American Medical Association and the American Osteopathic Association master files and included nonfederal, office- and hospital-based physicians who spent at least 20 hours a week in direct patient care. Residents and fellows were excluded. Questions on information technology were added to the 2000-01 survey and continued in the 2004-05 survey. The 2004-05 survey includes responses from more than 6,600 physicians, and the response rate was 52 percent. More detailed information on survey methodology can be found at www.hschange.org.