HSC Research Brief No. 3

March 2008

Debra A. Draper, Laurie E. Felland, Allison Liebhaber, Lori Melichar

As the nation’s hospitals face increasing demands to participate in a wide range of quality improvement activities, the role and influence of nurses in these efforts is also increasing, according to a new study by the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC). Hospital organizational cultures set the stage for quality improvement and nurses’ roles in those activities. Hospitals with supportive leadership, a philosophy of quality as everyone’s responsibility, individual accountability, physician and nurse champions, and effective feedback reportedly offer greater promise for successful staff engagement in improvement activities.

Yet hospitals confront challenges with regard to nursing involvement, including: scarcity of nursing resources; difficulty engaging nurses at all levels—from bedside to management; growing demands to participate in more, often duplicative, quality improvement activities; the burdensome nature of data collection and reporting; and shortcomings of traditional nursing education in preparing nurses for their evolving role in today’s contemporary hospital setting. Because nurses are the key caregivers in hospitals, they can significantly influence the quality of care provided and, ultimately, treatment and patient outcomes. Consequently, hospitals’ pursuit of high-quality patient care is dependent, at least in part, on their ability to engage and use nursing resources effectively, which will likely become more challenging as these resources become increasingly limited.

![]() n recent years, emphasis on improving the quality of care provided by the nation’s hospitals has increased significantly and continues to gain momentum. Because nurses are integral to hospitalized patients’ care, nurses also are pivotal in hospital efforts to improve quality. As hospitals face increasing demands to participate in a wide range of quality improvement activities, they are reliant on nurses to help address these demands.

n recent years, emphasis on improving the quality of care provided by the nation’s hospitals has increased significantly and continues to gain momentum. Because nurses are integral to hospitalized patients’ care, nurses also are pivotal in hospital efforts to improve quality. As hospitals face increasing demands to participate in a wide range of quality improvement activities, they are reliant on nurses to help address these demands.

Gaining a more in-depth understanding of the role that nurses play in quality improvement and the challenges nurses face can provide important insights about how hospitals can optimize resources to improve patient care quality.

Data for this work were collected primarily through interviews with hospital executives in four communities: Detroit, Memphis, Minneapolis-St. Paul and Seattle (see Data Source). Specific domains explored with respondents included:

![]() uality improvement is not a new concept for hospitals. Hospitals have had quality improvement departments and employed related staff for many years. What is new, however, is the proliferation of these activities and the escalating pressure on hospitals to participate.

uality improvement is not a new concept for hospitals. Hospitals have had quality improvement departments and employed related staff for many years. What is new, however, is the proliferation of these activities and the escalating pressure on hospitals to participate.

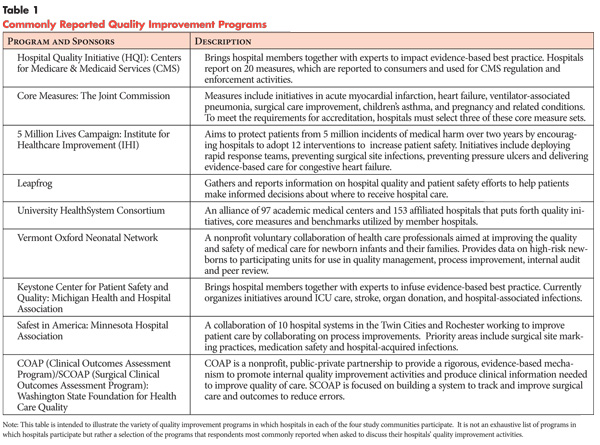

Across all four communities, hospital respondents reported increasing demands to participate in a wide array of programs sponsored by a variety of entities, such as accreditation and regulatory bodies, quality improvement organizations, medical specialty societies, state hospital associations, and health plans (see Table 1). In addition to these external programs, respondents also reported hospitals engaging in a variety of internal quality improvement activities, including those based on patient and employee feedback.

There are various pressures that influence hospital decisions to participate in different quality improvement activities. In 2002, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, now known as The Joint Commission, began requiring hospitals seeking accreditation to report core quality measures. With payers often requiring accreditation for reimbursement, this created strong financial incentives for hospitals to participate. In 2003, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) launched the voluntary Hospital Quality Initiative (HQI), under which hospitals report a core set of quality measures for display on a public Web site, www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov.

The public nature of the HQI information pressures hospitals not only to participate by reporting, but also to perform well relative to competitors and show improvement. The pressures to report to CMS intensified with the passage of the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement and Modernization Act (MMA) of 2003, which created financial incentives for hospitals to participate in HQI or receive a 0.4 percentage-point reduction in annual payment updates.1 Beginning in 2007, nonparticipating hospitals’ annual payment updates were reduced by 2 percentage points. More recently, CMS announced it would cease paying hospitals for some care resulting from medical errors.2

Other entities, such as state hospital associations and health plans, also have increased collection and public reporting of hospital quality information. Increasingly, health plans are linking reporting of quality information to payment. Respondents believe that expectations from payers, consumers and others for more and better information about provider quality will continue to grow, requiring hospitals to respond to stay competitive. As one hospital chief nursing officer (CNO) said, when major employers start using quality data to steer their employees to particular providers, “That’s a business survival decision that we have to make.”

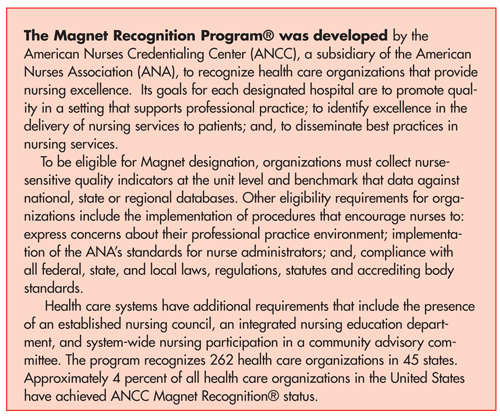

Hospitals often participate in specific quality improvement activities to support staff professional interests. This was often the impetus behind hospitals seeking Magnet Program status for nursing excellence from the American Nursing Association (see box). According to respondents, these types of activities also enhance the facility’s reputation, an increasingly important factor in the current marketplace to not only differentiate among competitors, but also to help with such activities as physician and nurse recruitment.

Nurses are “the largest deliverer of health care in the U.S.,” according to a representative of an accrediting organization, and as hospital participation in quality improvement activities increases, so does the role of nursing. Universally, respondents described how vital nurses are to hospitals; that nursing care is a major reason why people need to come to a hospital. As one hospital CEO said of nurses, they are the “heart and soul of the hospital.”

Respondents reported that nurses are well positioned to serve on the front lines of quality improvement since they spend the most time at the patient’s bedside and are in the best position to affect the care patients receive during a hospital stay. As one hospital CNO noted, “Nurses are the safety net. They are the folks that are right there, real time, catching medication errors, catching patient falls, recognizing when a patient needs something, avoiding failure to rescue.” Other respondents described nurses in similar veins as the “eyes and ears” of the hospital and being in a particularly good position to positively influence a patient’s experience and outcomes.

![]() cross the board, respondents emphasized that a supportive hospital culture is key to making important advances in quality improvement. They identified several key strategies that help foster quality improvement, including:

cross the board, respondents emphasized that a supportive hospital culture is key to making important advances in quality improvement. They identified several key strategies that help foster quality improvement, including:

While respondents acknowledged these are important factors, there was considerable variation in the extent to which each hospital in the four communities has been able to incorporate these strategies into their individual cultures.

To create a hospital culture supportive of quality improvement, respondents stressed the importance of hospital leadership being in the vanguard to engage nurses and other staff. As a representative of an accrediting organization said, “For any quality improvement project to be successful, the literature shows that support has to trickle down from the top. That is important to success. That level of sponsorship has to be there for quality improvement to be successful. Not only nursing leadership, but across the board from the CEO down.”

As an example, the CEO of one hospital supported nurses in their efforts to better track and address the prevalence of bedsores among patients, even though doing so required that the information be reported to a state agency. Despite the potential for negative attention for the hospital, the CEO encouraged nursing staff to take ownership of a quality problem where there was an opportunity to improve patient care.

Hospital respondents expressed the importance of not just “paying lip service” to quality improvement, but also to dedicating resources to these activities. Some hospitals, for example, have reportedly expanded their nursing leadership infrastructure in recent years and some have created new nursing positions dedicated to quality improvement (e.g., director of nursing quality). Some respondents reported providing nurses with more support for administrative tasks such as data collection and analysis.

A hospital culture that espouses quality as everyone’s responsibility is reportedly better positioned to achieve significant and sustained improvement. While hospital respondents characterized the role of nurses in quality improvement as crucial, they also emphasized that nursing involvement alone is insufficient because “it is not simply nursing’s work or quality’s work; it is the work of the whole organization.”

For most hospitals, quality improvement efforts transcend departments, and nurses are reportedly involved, at some level, in virtually all of these activities because of their clinical expertise and responsibility for the day-to-day coordination of care and other services for patients. However, respondents said that to really improve quality, you have to have every staff member engaged, including other clinical staff, such as physicians, pharmacists and respiratory therapists, as well as nonclinical staff, such as food service, housekeeping and materials management. As a director of quality improvement stated, “Nursing practice occurs in the context of a larger team. Even on a pressure ulcers team, even though it is primarily a nursing-focused practice, you have the impact of nutrition, for example. On cases that are clinically challenging, like transplants, you would also have the impact of our surgeons, for instance.”

Across hospitals, broad-based staff inclusion in quality improvement varies. One hospital CNO reported, “I wish quality improvement could be done in a more multidisciplinary fashion. We tend to hand off pieces to each other and work in silos. Nurses themselves are very involved, but a lot of what happens is beyond just the nurse. I would like to be able to get the entire group, from nurses to pharmacy to lab techs to medical records to physicians together in a multidisciplinary way to say, ‘Something happened. Let’s check what went wrong together.’” To confront this silo mentality, one hospital moved the reporting relationship of the quality improvement department to the CEO as a signal to staff that quality improvement was not just a nursing activity but a responsibility of all staff.

Another key component of a hospital culture conducive to quality improvement is encouraging individual ownership and accountability for patient safety and quality, according to respondents. In one hospital, for example, there were delays in notifying physicians of critical lab results. According to the hospital quality improvement director, when nurses took ownership of the process and started collecting the data, they were able to determine the problem and address it. Another respondent noted that if nurses identify a problem and are encouraged to take responsibility for fixing it, it is analogous to “the difference between reading the memo and getting it done and writing the memo and getting it done,” the latter of which is significantly more likely to create and sustain needed change.

Hospitals have pursued various strategies to increase staff ownership and accountability. The most commonly reported was to more explicitly include and detail quality improvement responsibilities in job descriptions and performance evaluations for staff and in contracts with physicians. Respondents discussed that this was important for all staff, not just leadership. A hospital CEO stated, “We are trying to drive it down further to the nursing staff on the floor, or in the unit, or in the ER, and say, it is part of your job requirements to help us improve patient care and improve patient satisfaction.”

Hospitals also use other types of rewards to encourage staff ownership and accountability. Respondents discussed a range of ways to reward staff, including public acknowledgement by leadership in staff meetings, writing them thank you notes, formal award recognition ceremonies and dinners, and sending them to national quality improvement meetings, such as those sponsored by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement.

Identifying and promoting nurses and physicians to champion quality improvement efforts reportedly helps empower staff to engage in and move quality improvement initiatives forward. One hospital CEO found nursing champions particularly important—that even though the academic facility is very involved in quality, when nurses champion a project, they are able to achieve “real, sustained improvement.”

Others reported that having physician champions on quality improvement projects is helpful because they can exert peer pressure to solicit participation and compliance from other physicians. Additionally, physician champions are particularly effective in providing nurses the support they need to confront a physician when the nurse sees “something that flies in the face against what’s right, like a physician not washing their hands.” As a hospital CEO stated, “Giving someone permission to enforce compliance and them feeling comfortable doing it are two different things.” Physician and nurse champions help ease this tension.

Several respondents said that hospitals’ employment of physicians, rather than relying on voluntary, community-based, physicians, helps to not only generate physician buy in, but to also create physician champions. When physicians and nurses are both employed, they tend to face similar accountability expectations and have closer working relationships than when the nurses are employees, but the physicians are not. As one hospital CEO said, “We have a closed medical staff, and so our physicians have more time to do quality work. We are lucky because they provide support for our nurses. This is not the case for all community hospitals. In community hospitals that have a voluntary medical staff, the nurses have to support the physicians’ quality work because the physicians are volunteers. So, people prop them up more, and nurses are expected to do it all for them.” Many respondents advocated that strong physician-nurse partnerships are essential to achieving quality improvement and sustaining the accomplishments.

Hospitals that actively communicate with and provide timely and useful feedback to staff reportedly are more likely to foster quality improvement than those that do not. As one hospital CNO noted, “We have tried to be as transparent as we can and share as much information as we can with our nursing staff. They get a lot of information and that helps them stay motivated and engaged in the process.”

Hospitals use a variety of feedback mechanisms. One widely used mechanism is a periodic scorecard that provides information on how performance, including quality improvement, is progressing toward goals. According to respondents, the information is typically provided at both the hospital and individual unit levels and is visibly displayed throughout the hospital for all staff to see. Other commonly reported methods of providing feedback on quality improvement include newsletters, staff training, new employee orientation, e-mail communications, unit-based communication boards and staff meetings. Respondents cautioned, however, that the key to effective feedback is not just the amount of information provided, but also how meaningful that information is for staff. As a hospital CNO explained, “Our quality regimes until now have just been leaning toward giving numbers. That doesn’t affect nurses’ practice, but if you give them more detail, it makes it more meaningful for them.”

Two-way feedback between hospital leadership and staff is also important. Several respondents reported using patient safety rounds as one way of facilitating this. In one hospital, executives periodically visit individual patient care units and sit down and talk with staff. One of the questions they ask of staff is, “What keeps you awake at night?,” referring to any patient quality or safety concerns staff may have. This process has reportedly been effective in identifying areas for improvement, such as the need for improved response times for the delivery of supplies and medications to patient care units.

![]() ospital respondents reported several challenges related specifically to nurses’ involvement in quality improvement, including:

ospital respondents reported several challenges related specifically to nurses’ involvement in quality improvement, including:

The scarcity of nurses is a major challenge for hospitals because it impacts not only their ability to provide nursing coverage for patient care, but also to provide adequate nursing resources for other key activities, such as quality improvement. Hospital respondents in two of the communities—Memphis and Seattle—reported being significantly affected by a nursing shortage, which some believed would only worsen, particularly as more nurses age out of the workforce and demand continues to exceed supply.3

Respondents noted that there is a limit to how much work, including quality improvement, can be added to nurses who are already short staffed. As one quality improvement director stated, “Our shortage of staffing means that we’d rather leave the nurse in the care role vs. the process change role.” Hospital respondents in the two communities that did not report a current nursing shortage said that if such a shortage were to emerge, the tendency would be to take nurses “away from the table and onto the floor,” making it hard to keep quality improvement efforts on track.

When hospitals are unable to employ an adequate number of nurses for patient care, they often are forced to use agency or temporary nurses. As hospital respondents discussed, it is exceedingly difficult to get these nurses engaged and invested in quality improvement because they may be at your hospital one day but at another the next day. A hospital CNO said that with heavy reliance on agency or temporary staff, “you will have a hard time making people available to participate in quality improvement activities and you will have a hard time seeing improvement because you aren’t going to have the consistency that you need.”

Similar to the challenges with the use of agency or temporary nurses, staffing composition—the mix of full-time and part-time nurses—may also influence hospitals’ ability to engage nurses in quality improvement. As a hospital CEO discussed, it is easier to make change with full-time staff “because they are here more often and you are in front of them more often. It is that much more difficult with part-time folks because you don’t have the face time with them.” Sometimes, however, part-time staff present what one CNO described as “a double-edged sword.” That is, while some part-time staff just want to work part-time and not be engaged in activities other than bedside nursing, others want to be more engaged, particularly in activities like quality improvement. The part-time status of nurses provides greater flexibility for the hospital because they can increase patient care staffing and participation in quality improvement without having to hire someone new.

The staffing requirements associated with quality improvement often force hospitals to balance quality improvement activities with many other competing priorities. While there is the belief that quality improvement can ultimately lead to greater efficiencies, the activity itself is often very resource intensive. Though many assert there is a business case for quality—that engaging in quality improvement activities will be cost neutral or reduce costs in the long-run—few hospitals have been able to demonstrate such savings and consider quality improvement activities an added expense. However, some hospital respondents expressed the belief that as quality improvement activities become better integrated into the day-to-day work of nurses (and other staff), “the right thing to do will also be the easiest thing to do.” That is, to the extent that quality improvement reduces, if not prevents, complications, cost savings are likely to be realized from less nursing labor needed to fix problems.

Another dilemma hospitals face is that they want their best nurses at the bedside caring for patients and these same nurses leading their quality improvement activities. This poses an even greater quandary when nurses are in scarce supply. Some respondents said that trying to balance nurses’ work at the bedside with their involvement in quality improvement activities has sometimes resulted in nurses receiving mixed messages about their role in quality improvement.

As one hospital respondent stated, “On the one hand, we are saying, ‘Yeah, we are all responsible,’ and then as soon as the rubber hits the road, it’s ‘Don’t add another thing to my nurses’ plate.’” Respondents discussed that inadequate engagement of staff nurses reduces the likelihood of their buy in and support because they may not understand the rationale and impetus behind a particular quality improvement initiative. It also can diminish the importance of quality improvement or give the impression that the related work is more of a burden than an opportunity. As a quality improvement program respondent surmised, quality improvement is greatly encouraged by “bringing bedside staff into the process vs. informing them what they’ll do.”

Although a goal of many hospitals is to substantively engage all nurses in quality improvement activities, there is considerable variation in the degree to which they are able to accomplish this. Respondents reported that often, a disproportionate share of the responsibility falls to nursing management. According to a hospital CNO, “Most of our initiatives are led by management. Don’t get me wrong, I am management, and I think we have done a great job. But, if we are able to figure out a way to involve the front-line staff sooner, we would be able to improve our performance—not just improve our performance, but improve performance faster.” Quality improvement initiatives are reportedly much more successful in cases where they have developed from the ground up and bedside staff—nurses and others—have “grabbed hold and made them their own.”

Hospitals also face ever-growing demands to participate in more quality improvement activities, many of which are viewed as duplicative. The lack of standardization in quality measurement and reporting intensifies the challenge, according to hospital respondents. A hospital CEO reported, “It seems like every time we turn around there are six more initiatives coming down. I’m a believer in pace of work. What we take on, let’s do it, define success and then take on other things. It’s not that we’re going to stop doing quality, but you get so much on your plate, you’re not affecting the outcome of any of it.” Respondents say too that the increasing demands often lead to staff frustration when they think that the hospital is trying to fix everything at once. With nurses assuming many of the added responsibilities, balancing various responsibilities becomes even more challenging.

Many hospital respondents have or are considering scaling back participation in the number of quality improvement activities. A hospital CNO said that her hospital is “less willing to jump on every train that goes through.” Generally, hospital respondents reported giving more thought to how an initiative would contribute to specific goals. For example, several respondents discussed the importance of participating in activities that provide data on how the hospital compares with other hospitals. Benchmarking provides important information to communicate with staff about the hospital’s performance and is particularly useful in revealing significant differences—both good and bad. A representative of a quality improvement program suggested hospitals, ultimately, just need to identify what makes sense for their patient populations, and that the initiative being contemplated should address an identified need.

The administrative burden associated with quality improvement is reportedly so high that it often precludes nurses from having a more substantive role. As a hospital quality improvement director said, “With all the time spent on data collection and analysis, it’s hard to find the time to develop and implement changes.” Many respondents, however, were optimistic that enhanced information technology systems and more automated processes could relieve much of the labor-intensive work—such as manual chart reviews—that is often required for data collection and reporting, freeing nurses to do more engaging and rewarding quality improvement work.

An additional benefit of better information technology systems, respondents said, is to provide nurses with more “real-time” data. This, they believe, would be particularly beneficial in increasing nurses’ commitment to quality improvement because they would see in a timely manner that their work was making a difference. But some respondents cautioned that while more sophisticated information technology may ease some of the administrative burden of quality improvement, it may also create a potential pitfall of hospitals wanting to collect data on significantly more measures than they do currently, which would in fact, have a counter effect.

Respondents discussed that to optimize the role of nurses in quality improvement, it is important for nursing education programs to strengthen curricula to emphasize the concepts and skills needed to participate in quality improvement activities. As one hospital CEO stated, “Everyone needs to see their role as improving patient care and patient service. I think it will only get easier if the nursing schools make this philosophy part of the training process.”

Respondents also emphasized the need for effective continuing education programs for nurses in this area. That is, to better prepare nurses to be more adept at translating their observations of problems at the beside into an effective improvement effort. Highlighting this point, a quality improvement program representative explained, “Within the realm of nursing education, there is not the strength or emphasis on patient safety and understanding change as there should be.” He added, “In many cases, we are approaching caregivers with ideas that they’ve not necessarily been exposed to. Through academic experience, they should have the opportunity to hear about change models and understand some of the basics of the need for good information in making decisions. Data are all around nurses and they are using data for clinical decisions. We need them to understand how to use data to change practice.”

![]() mproving health care quality and patient safety are currently high on the national health agenda, a focus that will only intensify going forward. The stakes for hospitals to demonstrate high quality are increasing at the same time that resources—at least some critical ones—are becoming more limited. Consequently, hospitals will have to become more adept and sophisticated in discerning and pursuing activities that substantively contribute to the achievement of their quality, patient safety and other performance goals. This evolution also will require increased sophistication on the part of hospitals to optimize available resources to carry out their work.

mproving health care quality and patient safety are currently high on the national health agenda, a focus that will only intensify going forward. The stakes for hospitals to demonstrate high quality are increasing at the same time that resources—at least some critical ones—are becoming more limited. Consequently, hospitals will have to become more adept and sophisticated in discerning and pursuing activities that substantively contribute to the achievement of their quality, patient safety and other performance goals. This evolution also will require increased sophistication on the part of hospitals to optimize available resources to carry out their work.

However, determining the best use of resources, including nurses, will likely become more challenging for hospitals. Some areas of the country are currently faced with a shortage of nurses, and others are expected to see shortages develop, some of which are likely to be significant. As a result, hospitals will face growing tensions and trade-offs when allocating nursing resources among the many competing priorities of direct patient care, quality improvement and other important activities. While quality improvement is not solely the domain of nurses, they are integral to these activities because of their day-to-day patient care responsibilities. Within this evolving environment, hospitals will need to guard against diminishing the involvement of nurses in quality improvement activities where they are likely to have the greatest influence and impact.

To examine the role of nurses in hospital quality improvement activities, information was collected from hospitals in the four initial communities selected to participate in the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Aligning Forces for Quality Program—a program focused on performance reporting, quality improvement by health care providers, and engagement of consumers on health care quality issues. The four communities are Detroit, Memphis, Minneapolis-St. Paul, and Seattle.

In each community, two of the larger hospitals were judgmentally selected to conduct interviews, for a total of eight hospitals. To provide a range of perspectives, we interviewed the leadership in each hospital, including the chief executive officer, the chief nursing officer, and the director of quality improvement. We also interviewed respondents representing key national- and state-level accreditation and quality improvement programs to obtain additional insights and perspectives on the issues. The findings are based on semi-structured phone interviews conducted by two-person interview teams between February and August 2007 with approximately 30 respondents. We used Atlas.ti, a qualitative software package, to analyze the interview data.

Acknowledgement: This research was funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.