Community Report No. 03

Winter 1999

Claudia Williams, Jon B. Christianson, Melanie L.E. Barraclough, Daniel S. Gaylin

![]() n September 1998, a team of researchers visited Boston, Mass., to study that

community’s health system, how it is changing and the impact of those changes on

consumers. More than 60 leaders in the health care market were interviewed as part

of the Community Tracking Study by Health System Change (HSC) and The Lewin Group.

Boston is one of 12 communities tracked by HSC every two years through site

visits and surveys. Individual community reports are published for each round

of site visits. The first site visit to Boston, in September 1996, provided baseline

information against which changes

are being tracked. The Boston market includes the city of Boston and its suburbs.

n September 1998, a team of researchers visited Boston, Mass., to study that

community’s health system, how it is changing and the impact of those changes on

consumers. More than 60 leaders in the health care market were interviewed as part

of the Community Tracking Study by Health System Change (HSC) and The Lewin Group.

Boston is one of 12 communities tracked by HSC every two years through site

visits and surveys. Individual community reports are published for each round

of site visits. The first site visit to Boston, in September 1996, provided baseline

information against which changes

are being tracked. The Boston market includes the city of Boston and its suburbs.

![]() fter a series of health plan and

hospital mergers leading up to HSC’s site visit in 1996, Boston’s

health care market entered a period of greater

organizational stability. This trend continues today. Five nationally renowned

not-for-profit organizations still dominate - two large care systems based

in academic medical centers, Partners and CareGroup, and three large health plans,

Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, Tufts Associated Health Plan and Blue Cross and Blue

Shield of Massachusetts (BCBSM). While there have been some shifts in the competitive

position of these entities, no single organization or sector controls the market.

fter a series of health plan and

hospital mergers leading up to HSC’s site visit in 1996, Boston’s

health care market entered a period of greater

organizational stability. This trend continues today. Five nationally renowned

not-for-profit organizations still dominate - two large care systems based

in academic medical centers, Partners and CareGroup, and three large health plans,

Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, Tufts Associated Health Plan and Blue Cross and Blue

Shield of Massachusetts (BCBSM). While there have been some shifts in the competitive

position of these entities, no single organization or sector controls the market.

Alongside this continuity there have been important changes in the market:

- Boston Retains Distinctive Market Features

- Government Continues to Act as a Shaping Force

- As Plans Retrench, Provider Systems Strengthen Market Position

- No Immediate Gain Seen from Hospital Consolidation

- Large Care Systems Focus on Managing Risk Contracts

- Concerns Raised About Control of Referrals and Care Management

- Medicaid Enrollment Increases But Fewer Plans Participate

- Issues to Track

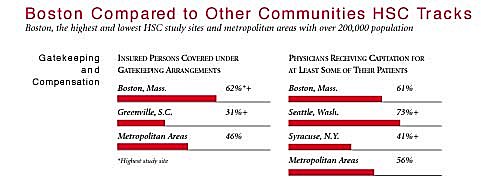

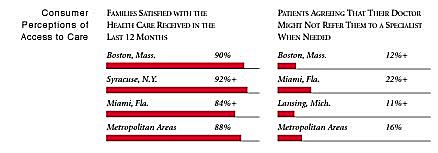

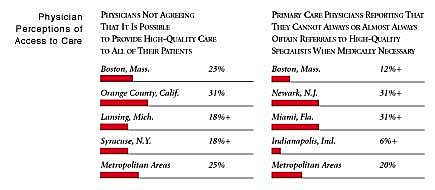

- Boston Compared to Other Communities HSC Tracks

- Background and Observations

![]() he Boston health care market -

with a 46 percent HMO penetration rate - has several features that make it

different from other high managed care communities. It is dominated by three

well-regarded not-for-profit health plans and is influenced by an activist

government with a strong consumer orientation. A large proportion of families

report being satisfied with their health care-more than in other HSC study sites

with high managed care penetration. There are more hospital beds and physicians

per capita, and health costs are significantly higher than the national average.

These costs are viewed by purchasers, plans and providers as a reasonable trade-off

for access to Boston’s academic medical

centers, key contributors to the local economy. Indeed, desire to maintain teaching

and research capabilities was

the main justification for the merger of Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham

and Women’s Hospital that created Partners in 1993.

he Boston health care market -

with a 46 percent HMO penetration rate - has several features that make it

different from other high managed care communities. It is dominated by three

well-regarded not-for-profit health plans and is influenced by an activist

government with a strong consumer orientation. A large proportion of families

report being satisfied with their health care-more than in other HSC study sites

with high managed care penetration. There are more hospital beds and physicians

per capita, and health costs are significantly higher than the national average.

These costs are viewed by purchasers, plans and providers as a reasonable trade-off

for access to Boston’s academic medical

centers, key contributors to the local economy. Indeed, desire to maintain teaching

and research capabilities was

the main justification for the merger of Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham

and Women’s Hospital that created Partners in 1993.

While cost cutting has not been the major focus of attention, some organizations have tried to reduce operating costs in the last two years. BCBSM reports that it eliminated 50 percent of its staff in an effort to shed unprofitable business and streamline its operations. Boston Medical Center also made significant cuts, and Harvard Pilgrim recently announced plans to lay off at least 100 staff members.

At the same time, employers are accepting moderate increases on an already high premium base, although they are pushing plans to deliver added benefits and better customer service in return. Premiums in Boston rose by about 3 to 5 percent in 1998, on par with the national increase of 3.3 percent. Many observers predict that plans will press for larger premium increases in the range of 8 to 10 percent for 1999 because of their poor financial performance over the last two years.

![]() tate government has long played a

major role in shaping the Boston health care market. Extensive protections and mandates

are already in place in Massachusetts, and the state government continues to play an

active, behind-the-scenes role in shaping the health care market. Health care

organizations pay close attention to concerns voiced by legislators and government

officials and often proactively change their strategies to address these issues. At

the same time, health care organizations try to achieve their competitive goals

through policy initiatives.

tate government has long played a

major role in shaping the Boston health care market. Extensive protections and mandates

are already in place in Massachusetts, and the state government continues to play an

active, behind-the-scenes role in shaping the health care market. Health care

organizations pay close attention to concerns voiced by legislators and government

officials and often proactively change their strategies to address these issues. At

the same time, health care organizations try to achieve their competitive goals

through policy initiatives.

Although little new legislation has been passed over the last two years, much debate has taken place on managed care issues. Reforms that were proposed in 1998 but did not pass would have introduced more state oversight of managed care plans, instituted a standardized appeals process and increased state- mandated services by requiring coverage for reasonable emergency room visits. Similar laws are expected to be proposed in the next legislative session.

As in the past, this year’s managed care proposals mobilized employers and health plans in opposition. The managed care debate also brought physicians and consumer groups into an unprecedented alliance in support of increased state oversight. The recent legislative effort has had a lasting impact on the market. Plan respondents indicate that local HMOs that have long been highly regarded have suddenly become unpopular.

![]() onfronted by increasing

anti-managed care sentiment, plans are perceived to be assuming a lower

profile than two years ago. They seem to have limited their scope of activities,

selling off owned provider capacity, reducing product lines and transferring some

responsibilities to providers. BCBSM sold its nine health clinics to MedPartners

to support its goals of generating cash and returning to core functions. Harvard

Pilgrim spun off its

14 health centers, the centerpiece of the original Harvard Community Health Plan,

into a physician-directed enterprise, Harvard Vanguard.

onfronted by increasing

anti-managed care sentiment, plans are perceived to be assuming a lower

profile than two years ago. They seem to have limited their scope of activities,

selling off owned provider capacity, reducing product lines and transferring some

responsibilities to providers. BCBSM sold its nine health clinics to MedPartners

to support its goals of generating cash and returning to core functions. Harvard

Pilgrim spun off its

14 health centers, the centerpiece of the original Harvard Community Health Plan,

into a physician-directed enterprise, Harvard Vanguard.

The major plans have pursued regional strategies by affiliating with, buying or establishing plans in the other New England states to offer products to multistate employers. At the same time, there have been shifts in the market position of the three large plans. Harvard Pilgrim is still the largest plan in Massachusetts, but Tufts has moved into second place, due in large part to the strength of its Secure Horizons Medicare managed care product. BCBSM, once the largest insurer by far, is now in third place. While the Blues plan appears to be on the upswing, it has faced significant problems over the last few years, with financial losses that prompted close oversight by the state’s Department of Insurance and an enrollment freeze on its Medicare risk plan initiated by the federal Health Care Financing Administration.

Meanwhile, local provider systems appear to be operating from a position of relative strength, as they move from a period of finding partners to one of making existing partnerships work. They have expanded their range of activities in the last two years, as they implemented mergers, built networks and established risk management infrastructures. Respondents point out that large academic hospitals were notably silent during recent managed care debates in the legislature. These organizations seem well served by having plans take the heat from consumers and advocates.

Other health care entities in Boston are trying to increase their market power, by affiliating either with the five major organizations or with other entities. For example, Neighborhood Health Plan (NHP), a Medicaid HMO formed by the city’s community health centers, was recently acquired by Harvard Pilgrim Health Care. New England Medical Center, one of the last unaffiliated academic medical centers, was recently acquired by Rhode Island-based Lifespan. And Lahey Clinic recently announced a new partnership with CareGroup, after Lahey’s merger with the New Hampshire-based Hitchcock Medical Center fell apart. These changes highlight the continued importance for plans and providers of being part of large, regionally powerful organizations.

![]() y the time of the 1996 site visit,

three large care systems had formed from a series of mergers with the stated goals of

gaining market power and reducing excess capacity. Different consolidation strategies

were pursued, with some integrating more than others. Two years later, it appears that

the systems that did more to integrate and consolidate have not yet seen a payoff in

market position.

y the time of the 1996 site visit,

three large care systems had formed from a series of mergers with the stated goals of

gaining market power and reducing excess capacity. Different consolidation strategies

were pursued, with some integrating more than others. Two years later, it appears that

the systems that did more to integrate and consolidate have not yet seen a payoff in

market position.

Overall, Partners appears to be in a better competitive position than the other two large care systems, CareGroup and Boston Medical Center, which both did more to integrate and consolidate. However, some have noted that Partners’ success may hinge more on the reputation and access to capital of its two hospitals than on its integration strategy.

![]() he number of lives covered under

providers’ risk-based contracts has increased substantially over the last two years,

and the two large academic medical center-based systems - Partners and CareGroup-have

turned greater attention to implementing these contracts

and managing their provider networks. Although these agreements still represent a

relatively small share of the academic hospitals’ business and reportedly have not

been profitable, they are seen to be important because the number of risk contracts

is expected to grow, and because the networks are significant referral sources for

the hospitals. The two systems have apparently invested heavily in the information

and staff infrastructure

needed to support these contracts, and observers predict they will push for

payment increases when their plan

contracts are renegotiated.

he number of lives covered under

providers’ risk-based contracts has increased substantially over the last two years,

and the two large academic medical center-based systems - Partners and CareGroup-have

turned greater attention to implementing these contracts

and managing their provider networks. Although these agreements still represent a

relatively small share of the academic hospitals’ business and reportedly have not

been profitable, they are seen to be important because the number of risk contracts

is expected to grow, and because the networks are significant referral sources for

the hospitals. The two systems have apparently invested heavily in the information

and staff infrastructure

needed to support these contracts, and observers predict they will push for

payment increases when their plan

contracts are renegotiated.

Partners and CareGroup have established management service organization (MSO)-like structures to manage this business, and these entities are now considered the dominant physician contracting organizations in the Boston market. Partners Community HealthCare, Inc., has 915 primary care physicians in its network, while CareGroup’s Provider Services Network has about 500. Both organizations have reportedly slowed acquisitions of physician practices, favoring affiliations and joint ventures.

For most of these risk contracts, the MSO is slated to receive 70 to 80 percent of the premium for enrollees from plans. Population-based budgets are established, and providers are paid on a fee-for-service basis with year-end reconciliation. The large care systems pass some of the risk along to risk units, each consisting of a group of physicians, such as the Massachusetts General physician group, and its affiliated hospital. Risk is assigned to these units based on the enrollee’s choice of primary care physician.

The increasing focus on risk contracts has highlighted the underlying tensions between academic medical centers and community hospitals about how to structure payments to the multiple risk units within their networks. Physicians affiliated with the academic medical centers want to institute risk adjustment methodologies to avoid penalties for attracting sicker patients who require more services.

Meanwhile, physicians based at community hospitals are concerned that the drive for better risk adjustment methodologies is part of a larger academic medical center strategy to attract patients who had historically received care at community hospitals. This concern may ultimately drive community hospitals and their physicians to seek contracting vehicles that are less closely tied to the academic medical centers.

![]() ith the increase in risk contracts

comes the critical issue of who controls referrals. Partners and CareGroup are directing

patient referrals for at-risk business to their own affiliated physicians and

hospitals. This raises concerns among health plans that patients will not have full access

to the broad networks they are building and promoting in response to purchaser and consumer

demands.

ith the increase in risk contracts

comes the critical issue of who controls referrals. Partners and CareGroup are directing

patient referrals for at-risk business to their own affiliated physicians and

hospitals. This raises concerns among health plans that patients will not have full access

to the broad networks they are building and promoting in response to purchaser and consumer

demands.

Plan reactions to provider referral management have varied. Harvard Pilgrim Health Care allows primary care providers who are at risk to make their own referral decisions but also allows enrollees to switch primary care providers at any time. Tufts Associated Health Plan has told providers who accept risk that enrollees must have access to the full Tufts network. BCBSM is also concerned about referral restrictions, especially since its signature asset is the breadth of its network, but it has not taken any action to counter referral management by providers, in part because it believes that could generate negative publicity.

The large care systems also want to control more care management functions to obtain a larger share of the capitated dollar. So far, plans have retained many care management responsibilities, including functions such as tracking and developing care plans for enrollees with chronic diseases. Plans have resisted handing over more responsibility on the grounds that care systems have not demonstrated their ability to implement system-wide quality improvement initiatives.

![]() edicaid enrollment increased

significantly as a result of program expansions in 1997 and 1998, when more than

100,000 children and adults gained coverage under the state’s Medicaid program,

MassHealth. With these expansions in place, some speculate that the state may

reduce funding for the uncompensated care pool, which pays for health services

for eligible uninsured.

edicaid enrollment increased

significantly as a result of program expansions in 1997 and 1998, when more than

100,000 children and adults gained coverage under the state’s Medicaid program,

MassHealth. With these expansions in place, some speculate that the state may

reduce funding for the uncompensated care pool, which pays for health services

for eligible uninsured.

The largest recipients of uncompensated care pool dollars, Boston Medical Center and Cambridge Hospital, have developed their own managed care programs to attract MassHealth enrollees and the uninsured. These two hospital systems negotiated higher Medicaid payments and approval to develop shadow managed care programs for the uninsured. Under these new programs, the hospitals use pool dollars to fund a comprehensive package of services for the uninsured. Rather than receiving treatment on an episodic basis, the uninsured enrollees will be linked with primary care providers and have access to preventive services.

While the number of Medicaid eligibles has grown, the number of HMOs serving the Medicaid market has declined. Two commercial plans in the market-BCBSM and Tufts Associated Health Plan-are no longer contracting with the state’s Medicaid program. The two plans had a combined enrollment of more than 60,000 Medicaid recipients and very broad provider networks. BCBSM withdrew because it was losing money on Medicaid. Tufts, which was also reported to have lost money on Medicaid, indicated it could not comply with the state’s increased reporting requirement along with the information technology demands presented by year 2000 computer problems.

With these two plans out, Harvard Pilgrim is the only remaining commercial plan serving the Boston Medicaid market. At the same time, the plan has stopped enrolling Medicaid beneficiaries in its large Pilgrim network, relying instead on the narrower networks of Harvard Vanguard and NHP providers. While beneficiaries still have access to a very broad network of providers under the state’s primary care case management (PCCM) program it maintains as an alternative to HMOs, there are concerns about the implications of these changes. According to market observers, changes in plans’ participation in Medicaid indicate that HMOs with broad and more loosely managed networks have had trouble surviving with the current rates. The state’s response to these new challenges remains to be seen.

![]() n the past two years, the

large academic care systems have grown stronger, and tensions have increased

between these

organizations and the three leading health plans. At the same time, Boston’s

health care system has retained many of its unique attributes: high managed

care penetration, high costs, renowned plans and academic hospitals and an

activist government. Emerging issues that could upset this stability include

the following:

n the past two years, the

large academic care systems have grown stronger, and tensions have increased

between these

organizations and the three leading health plans. At the same time, Boston’s

health care system has retained many of its unique attributes: high managed

care penetration, high costs, renowned plans and academic hospitals and an

activist government. Emerging issues that could upset this stability include

the following:

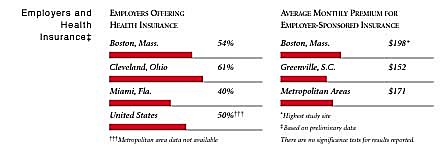

Boston, the highest and lowest HSC study sites and metropolitan areas with over 200,000 population

+Site value is significantly different from the mean for metropolitan areas over 200,000

population.

The information in these graphs comes from the Household, Physician and Employer

Surveys conducted in 1996 and 1997 as part of HSC’s Community Tracking Study. The

margins of error depend on the community and survey question and include +/- 2

percent to +/- 5 percent for the Household Survey, +/-3 percent to +/-9 percent

for the Physician Survey and +/-4 percent to +/-8 percent for the Employer Survey.

Boston Demographics

Sources:Boston, Mass. Metropolitan

areas above

200,000 populationPopulation, 19971 4,369,071 Population Change, 1990-19971 1.8% 6.7% Median Income2 $29,996 $26,646 Persons Living in Poverty2 10% 15% Persons Age 65 or Older2 14% 12% Persons with No Health Insurance2 9.1% 14%

1. U.S. Census, 1997

2. Household Survey

Community Tracking Study, 1996-1997

The Community Tracking Study, the major effort of HSC, tracks changes in the health system in 60 sites that are representative of the nation. Every two years, HSC conducts surveys in all 60 communities and site visits in the following 12 communities: