Issue Brief No. 94

March 2005

Ha T. Tu

More Americans are willing to limit their choice of physicians and hospitals to save on out-of-pocket medical costs, according to a new national study by the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC). Between 2001 and 2003, the proportion of working-age Americans with employer coverage willing to trade broad choice of providers for lower costs increased from 55 percent to 59 percent—after the rate had been stable since 1997. While low-income consumers were most willing to give up provider choice in return for lower costs, even higher-income Americans reported a significant increase in willingness to limit choice. Compared with other adults, people with chronic conditions were only slightly less willing to limit their choice of physicians and hospitals to save on costs. Perhaps as a result of growing out-of-pocket medical expenses in recent years, the proportion of people with chronic conditions willing to trade provider choice for lower costs rose substantially from 51 percent in 2001 to 56 percent in 2003.

![]() he proportion of working-age

Americans willing to limit their

choice of health care providers to save on

out-of-pocket medical costs grew significantly

between 2001 and 2003, according to

HSC’s Community Tracking Study (CTS)

Household Survey (see Data Source). In

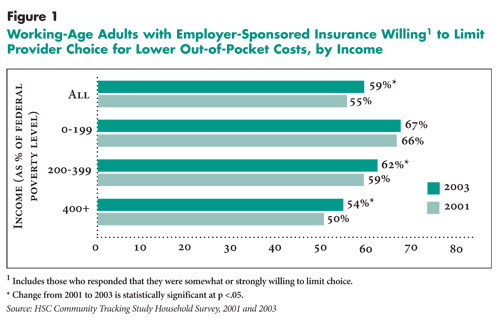

2003, 59 percent of adults 18 to 64 years old

covered by employer-sponsored insurance,

or 61 million people, agreed with the statement:

“I would be willing to accept a limited

choice of physicians and hospitals if I could

save money on my out-of-pocket costs for

health care” (see Figure 1). In 2001, 55 percent

of working-age adults with employer

coverage (58 million) were willing to make

this trade-off.

he proportion of working-age

Americans willing to limit their

choice of health care providers to save on

out-of-pocket medical costs grew significantly

between 2001 and 2003, according to

HSC’s Community Tracking Study (CTS)

Household Survey (see Data Source). In

2003, 59 percent of adults 18 to 64 years old

covered by employer-sponsored insurance,

or 61 million people, agreed with the statement:

“I would be willing to accept a limited

choice of physicians and hospitals if I could

save money on my out-of-pocket costs for

health care” (see Figure 1). In 2001, 55 percent

of working-age adults with employer

coverage (58 million) were willing to make

this trade-off.

Consumer demand for broader choice of health care providers was a driving force behind the managed care backlash of the mid-1990s. Under pressure from employers and consumers, health plans broadened provider networks and eased other care restrictions, but these changes were accompanied by rapidly rising health insurance premiums. Responding to rapidly rising premiums, many employers in 2002 began increasing patient cost sharing through higher deductibles, copayments and coinsurance. 1

Consumer choice-cost preferences were quite stable through 2001, making the change from 2001 to 2003 all the more notable (see Supplementary Table 1). A likely explanation for the change in consumer attitudes is that the growing burden of out-of-pocket medical costs is prompting a reassessment of the choice-cost trade-off.

|

![]() ncome influences a consumer’s willingness

to sacrifice choice to save on costs.

Among low-income adults with employersponsored

insurance—defined as family

income below 200 percent of the federal

poverty level, or $36,800 for a family of

four in 2003—two-thirds (67%) were willing

in 2003 to give up some choice of hospitals

and physicians. In comparison, 54

percent of adults with employer coverage

and incomes at least 400 percent of poverty

were willing to sacrifice choice. That

choice-cost preferences would differ by

income is not surprising, given that costs

would be of greater concern to people with

more limited financial resources. What

is surprising is that the magnitude of the

difference between the lowest and highest

income groups is not larger.

ncome influences a consumer’s willingness

to sacrifice choice to save on costs.

Among low-income adults with employersponsored

insurance—defined as family

income below 200 percent of the federal

poverty level, or $36,800 for a family of

four in 2003—two-thirds (67%) were willing

in 2003 to give up some choice of hospitals

and physicians. In comparison, 54

percent of adults with employer coverage

and incomes at least 400 percent of poverty

were willing to sacrifice choice. That

choice-cost preferences would differ by

income is not surprising, given that costs

would be of greater concern to people with

more limited financial resources. What

is surprising is that the magnitude of the

difference between the lowest and highest

income groups is not larger.

Although more affluent consumers were more inclined overall to favor provider choice over cost savings, even the highest income group has become increasingly willing to sacrifice choice (54% in 2003 vs. 50% in 2001). This result suggests that, while out-of-pocket costs may represent a heavier burden for low-income people, the impact of increased patient cost sharing likely has been felt across a broad spectrum of incomes.

![]() eople living with chronic conditions—such

as diabetes, asthma or depression—usually

require ongoing medical care and

often rely on specialty and hospital care

more than healthy adults. Therefore, it is

often assumed that people with chronic

conditions would be less willing to limit

their choice of providers to save on costs.

However, precisely because people with

chronic conditions need and use more

health services, they shoulder a higher outof-

pocket cost burden and have been hit

harder by the cost-sharing increases of the

past few years than healthy adults.

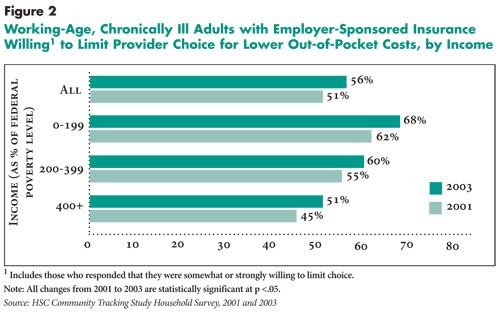

Among chronically ill adults with

employer-sponsored insurance, 56 percent

said they were willing to accept limited

choice of providers to save on costs in 2003

(see Figure 2). This level of willingness

is only slightly lower than the 59 percent

reported by all working-age adults with

employer coverage.

eople living with chronic conditions—such

as diabetes, asthma or depression—usually

require ongoing medical care and

often rely on specialty and hospital care

more than healthy adults. Therefore, it is

often assumed that people with chronic

conditions would be less willing to limit

their choice of providers to save on costs.

However, precisely because people with

chronic conditions need and use more

health services, they shoulder a higher outof-

pocket cost burden and have been hit

harder by the cost-sharing increases of the

past few years than healthy adults.

Among chronically ill adults with

employer-sponsored insurance, 56 percent

said they were willing to accept limited

choice of providers to save on costs in 2003

(see Figure 2). This level of willingness

is only slightly lower than the 59 percent

reported by all working-age adults with

employer coverage.

The same income patterns observed for all working-age adults also hold true for those with chronic conditions: The lower the income, the greater the willingness to sacrifice choice to save on out-of-pocket costs. Among the lowest-income group with chronic conditions, 68 percent would limit provider choice to get cost savings, compared with 51 percent of the highest-income group—a larger gap than for all workingage adults with employer coverage. Even for the highest-income group with chronic conditions, however, at least half now say they would sacrifice provider choice to save on costs—a substantial increase from the 45 percent who were willing to make this trade-off in 2001.

At each income level, willingness by chronically ill people to give up choice to gain cost savings has increased significantly: 5 to 6 percentage points—a substantial increase for a two-year period. These increases are larger than those reported by people without chronic conditions, and one likely explanation is that the increase in patient cost sharing has fallen most heavily on people with chronic conditions,2 making them more willing to sacrifice choice to save on costs. Within the lowest-income group, people with chronic conditions are now at least as likely as those without chronic conditions to be willing to give up choice—about two-thirds of both groups.

|

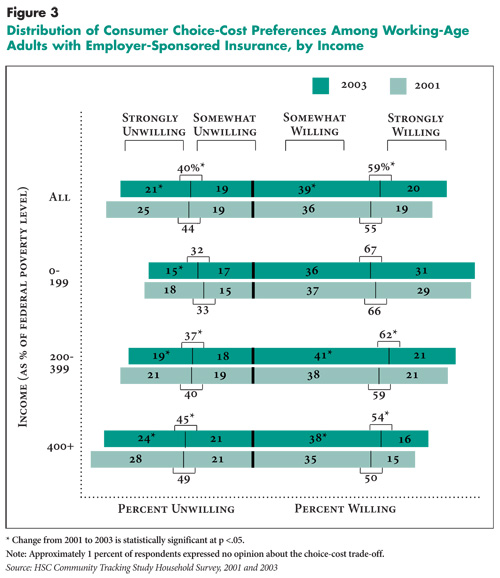

![]() mericans are deeply divided over the tradeoff

between unfettered choice of physicians

and hospitals and lowering their out-of-pocket

health costs. While 59 percent of working-age

adults with employer coverage would limit

provider choice for lower costs, a large minority

(40%) was unwilling. And substantial

minorities feel intensely about this hot-button

issue: 20 percent were strongly willing to

limit provider choice, while 21 percent were

strongly unwilling (see Figure 3).

mericans are deeply divided over the tradeoff

between unfettered choice of physicians

and hospitals and lowering their out-of-pocket

health costs. While 59 percent of working-age

adults with employer coverage would limit

provider choice for lower costs, a large minority

(40%) was unwilling. And substantial

minorities feel intensely about this hot-button

issue: 20 percent were strongly willing to

limit provider choice, while 21 percent were

strongly unwilling (see Figure 3).

Examining the changes in how intensely Americans feel about the choice-cost trade-off indicates Americans’ preferences are evolving along a continuum. Between 2001 and 2003, the proportion of all working-age adults with employer coverage strongly unwilling to limit provider choice declined from 25 percent to 21 percent. The somewhat willing category remained unchanged at 19 percent, but the category that gained the most was the somewhat willing category—36 percent in 2001 vs. 39 percent in 2003. The fact that this category, rather than the strongly willing category, saw the significant growth suggests that consumers’ growing willingness to limit choice may still be soft.

A similar pattern generally held true within each income group. For example, within the highest-income group, the proportion strongly unwilling to limit choice declined from 28 percent to 24 percent, while the proportion somewhat willing to limit choice grew from 35 percent to 38 percent between 2001 and 2003.

Across income groups, there was not much difference in the proportion of people with mild preferences—those who were somewhat willing or somewhat unwilling—about giving up choice to save costs. The most notable difference among the income groups lies in the proportion of those who express greater intensity in preferences: Low-income people with employer coverage were about twice as likely as higher-income people with employer coverage to be strongly willing to sacrifice choice (31% vs. 16%). At the opposite end, a much higher proportion of high-income people were strongly unwilling to limit choice compared with low-income people (24% vs. 15%).

|

![]() iven the diversity of choice-cost opinions,

it is striking that in recent years so many

employers have chosen to adopt broader

provider networks and increase patient cost

sharing. However, this trend in employer

insurance offerings is consistent with previous

research finding that firms’ health

benefit decisions are substantially influenced

by the preferences of the most highly compensated

workers.3 Recent changes in health

insurance offerings appear to have been

driven by a minority of influential, highly

paid workers dissatisfied with restricted

provider choice and other aspects of tightly

managed care.

iven the diversity of choice-cost opinions,

it is striking that in recent years so many

employers have chosen to adopt broader

provider networks and increase patient cost

sharing. However, this trend in employer

insurance offerings is consistent with previous

research finding that firms’ health

benefit decisions are substantially influenced

by the preferences of the most highly compensated

workers.3 Recent changes in health

insurance offerings appear to have been

driven by a minority of influential, highly

paid workers dissatisfied with restricted

provider choice and other aspects of tightly

managed care.

Offering a variety of insurance products representing different choice-cost options would satisfy the largest number of consumers. Yet, in recent years, many employers, faced with high administrative costs and risksegmentation issues that come with offering multiple health plans, have reduced the range of insurance options offered to workers. For example, fewer employees are now offered a health maintenance organization (HMO) as one of their insurance options. Only 47 percent of covered workers had access to an HMO product in 2003, down from 64 percent in 1996.4 Thus, among people willing to limit provider choice in return for lower costs, fewer are now able to exercise those preferences. And among consumers who maintained access to HMOs, some may have received more provider choice and paid more for it, than they would have preferred, because many HMOs have broadened their networks and eased care restrictions in exchange for higher premiums.

The finding that more insured Americans are willing to trade choice for lower costs raises the question of whether there may be renewed interest in restrictive provider network products. Employers and insurers have been reluctant to risk employee discontent by returning to restrictive networks, but with health costs continuing to outpace wage growth, resistance to these products may lessen. Rather than returning to traditional restrictive networks, some health plans have begun to introduce highperformance networks, which they hope will be more appealing to consumers because the narrow networks will consist of providers the plans have identified to be both cost effective and high quality.5

As an alternative to offering a range of health plans, a few employers and insurers are starting to offer products that carry multiple options. Tiered-provider networks, for example, allow consumers to make trade-offs between costs and provider choice instead of having health plans make the decisions, and so may prove more attractive to employers and consumers than more restrictive plans. Conceptually akin to tiered-pharmacy benefits, which have become the dominant form of prescriptiondrug coverage, tiered-provider networks have faced many operational challenges as well as strong resistance from providers, and have not been widely adopted by employers.6 These results, however, suggest that, in principle at least, tiered-provider networks and other insurance products that offer consumers multiple choice-cost options could attract a sizeable market.

As health cost increases continue to outpace income growth, more consumers may become willing to restrict their choice of providers to ease their out-of-pocket cost burden. And, some who are now only somewhat willing to limit choice may become more strongly inclined to do so and may seek access to lower-cost, limited-choice insurance products. Whether employers provide such options likely will depend on whether they perceive enough demand for those products from their highly paid workers—often the portion of their workforce for which recruitment and retention concerns are greatest. If employers don’t see the need to provide lower-cost options to satisfy highearning workers, then it is unlikely that these options will be offered broadly. Increasingly, consumers willing to limit provider choice for lower costs may find no way of satisfying those preferences. The result could be lower take-up of employer-sponsored insurance and an increase in uninsured Americans.

| 1. | Gabel, Jon, et al., “Health Benefits in 2003: Premiums Reach Thirteen-Year High As Employers Adopt New Forms of Cost Sharing,” Health Affairs, Vol. 22, No. 5 (September/October 2003). |

| 2. | Tu, Ha T., Rising Health Costs, Medical Debt and Chronic Conditions, Issue Brief No. 88, Center for Studying Health System Change, Washington, D.C. (September 2004). |

| 3. | Gruber, Jonathan and Michael Lettau, How Elastic Is The Firm’s Demand for Health Insurance?, Working Paper No. 8021, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, Mass. (November 2000). |

| 4. | Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Research and Educational Trust, Employer Health Benefits: 2004 Annual Survey. |

| 5. | “Payers Refine Cost-Sharing Techniques to Target Patient Behavior, Treatment Choice,” Managed Care Week, Dec. 8, 2003; “CIGNA Touts New Product as Key to Reversing Membership Losses,” Managed Care Week, Feb. 16, 2004. |

| 6. | Mays, Glen, Gary Claxton and Bradley Strunk, Tiered-Provider Networks: Patients Face Cost-Choice Trade-Offs, Issue Brief No. 71, Center for Studying Health System Change, Washington, D.C. (November 2003). |

The findings reported in this Issue Brief are based on an analysis of the CTS Household Survey, a nationally representative telephone survey conducted in 1996-97, 1998-99, 2000-01 and 2003. For discussion and presentation, we refer to a single calendar year for the first three surveys (1997, 1999 and 2001). The first three rounds of the survey contain information on about 39,000 adults aged 18- 64, including 28,000 with employersponsored insurance; the 2003 survey contains responses from about 30,000 adults aged 18-64, including 20,500 with employer-sponsored insurance.

To determine whether people had chronic conditions, the survey asked adult respondents whether they had been diagnosed with one of more than 10 chronic conditions and whether they had seen a doctor in the past two years for the condition. The list of chronic conditions includes asthma, arthritis, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart disease, hypertension, cancer, benign prostate enlargement, abnormal uterine bleeding and depression. Because the CTS list of conditions is not exhaustive, the estimate of the prevalence of chronic conditions is likely conservative.

Supplemental Table 1: Consumers’ Willingness to Limit Provider Choice for Lower Out-of-Pocket Costs, 1997-2003

ISSUE BRIEFS are published by the

Center for Studying Health System Change.

600 Maryland Avenue, SW, Suite 550

Washington, DC 20024-2512

Tel: (202) 484-5261

Fax: (202) 484-9258

www.hschange.org