Capacity Expands in Unrestrained Market:

Little Rock, Arkansas

Community Report No. 04

Winter 1999

Colleen Hirshkorn, Joy M. Grossman, Loel S. Solomon, Christina A. Andrews

![]() n September 1998, a team of researchers visited Little Rock, Ark., to study

that community’s health system, how it is changing and the impact of those changes

on consumers. More than 40 leaders in the health care market were interviewed as part

of the Community Tracking Study by the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC)

and The Lewin Group. Little Rock is

one of 12 communities tracked by HSC every two years through site visits and surveys.

Individual Community Reports are published for each round of site

visits. The first site visit to Little Rock, in September 1996, provided baseline information against which changes are being tracked. The Little Rock market includes the four-county Little Rock/ North Little Rock area.

n September 1998, a team of researchers visited Little Rock, Ark., to study

that community’s health system, how it is changing and the impact of those changes

on consumers. More than 40 leaders in the health care market were interviewed as part

of the Community Tracking Study by the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC)

and The Lewin Group. Little Rock is

one of 12 communities tracked by HSC every two years through site visits and surveys.

Individual Community Reports are published for each round of site

visits. The first site visit to Little Rock, in September 1996, provided baseline information against which changes are being tracked. The Little Rock market includes the four-county Little Rock/ North Little Rock area.

![]() n 1996, Little Rock was still a largely

traditional health care market, with a surplus of facilities and services, limited health

maintenance organization (HMO) enrollment and predominately fee-for-service arrangements.

However, several developments - including entry of national health care firms, the creation

of a state purchasing pool and new alliances between major hospitals and health plans -

signaled the promise of significant change. Yet by 1998, these changes had not unfolded

as expected. National firms have not usurped locals’ market share, and fee-for-service

continues to prevail. With few outside pressures, the alliance between the dominant

insurer, Arkansas Blue Cross Blue Shield, and the largest hospital system, Baptist

Health System, remains a focal point of competition.

n 1996, Little Rock was still a largely

traditional health care market, with a surplus of facilities and services, limited health

maintenance organization (HMO) enrollment and predominately fee-for-service arrangements.

However, several developments - including entry of national health care firms, the creation

of a state purchasing pool and new alliances between major hospitals and health plans -

signaled the promise of significant change. Yet by 1998, these changes had not unfolded

as expected. National firms have not usurped locals’ market share, and fee-for-service

continues to prevail. With few outside pressures, the alliance between the dominant

insurer, Arkansas Blue Cross Blue Shield, and the largest hospital system, Baptist

Health System, remains a focal point of competition.

Among the key changes shaping Little Rock’s health care system today:

- Local providers and plans are partnering with other national firms to bolster

their market position and hold the large insurer-hospital alliance in check.

- Physicians are establishing numerous ambulatory surgery centers and merging

their practices in an attempt to

protect their income and clinical autonomy.

- Both inpatient and outpatient capacity continue to expand, despite existing excess.

- Market Shaped by Few Restraints

- Threat of Outside Entrants Fades

- Local Entities Team Up with Other National Firms

- Powerful Insurer-Hospital Alliance Held in Check

- Physicians Move to Protect Income

- Efforts to Control Costs Are Challenged

- Issues to Track

- Little Rock Compared to Other Communities HSC Tracks

- Background and Observations

Market Shaped by Few Restraints

![]() he Little Rock health care market

continues to have few restraints imposed by purchasers or state policy. In an economy

dominated by small firms, there has been little organized purchaser activity, although

private purchasers’ sensitivity to both premium increases and restrictions on provider

choice has driven competition. The only significant purchaser initiative in recent years

was the creation of the Arkansas State Employee/Public School Personnel Insurance Board

in 1995. This initiative merged state employees and public school personnel under a joint

procurement process now covering about 73,000 individuals statewide, most of whom live in

the Little Rock area. The new purchasing process, along with a requirement that employees

pay a greater share of the premium for more expensive plans, spurred rapid growth in

managed care and prompted plans to position themselves to compete for enrollment.

he Little Rock health care market

continues to have few restraints imposed by purchasers or state policy. In an economy

dominated by small firms, there has been little organized purchaser activity, although

private purchasers’ sensitivity to both premium increases and restrictions on provider

choice has driven competition. The only significant purchaser initiative in recent years

was the creation of the Arkansas State Employee/Public School Personnel Insurance Board

in 1995. This initiative merged state employees and public school personnel under a joint

procurement process now covering about 73,000 individuals statewide, most of whom live in

the Little Rock area. The new purchasing process, along with a requirement that employees

pay a greater share of the premium for more expensive plans, spurred rapid growth in

managed care and prompted plans to position themselves to compete for enrollment.

Aside from this purchasing initiative, however, the state continues to play a limited role in shaping Little Rock’s health care market. Arkansas repealed its certificate-of-need regulations for acute care services soon after the federal mandate for these regulations was lifted, and state legislators rejected health reforms proposed in 1995, reinforcing their preference for a health system driven by market forces rather than one shaped by government. Ironically, at the same time, legislators passed a far-reaching any willing provider law that would have required all plans - including those protected by the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) - to contract with all providers willing to accept the plan’s fee schedule and other terms and conditions. However, the courts struck down the law, first in 1997 and again on appeal in 1998-thereby preventing it from being enforced.

Unlike the vast majority of states, Arkansas has not moved to enroll the Medicaid population in HMOs, relying instead on a primary care case management (PCCM) program as the major initiative to improve access and control costs for this population. The only other new policy development over the past two years has been the implementation of the state’s children’s health insurance program, separate from the federal Children’s Health Insurance Program. The state’s program has extended coverage to approximately 36,000 children-one-third of projected total enrollment-since it began in September 1997. While the program is expected to help begin to alleviate the state’s high rate of uninsurance, which is disproportionately concentrated among children and young adults, it is unlikely to have a major impact on the shape of competition in the market.

Threat of Outside Entrants Fades

![]() t the time of HSC’s first site visit

in late 1996, it was anticipated that the entry

of outsiders would change Little Rock’s health care environment. For the past

several years, a number of national health care companies had come to Little Rock

seeking to build market share. Among

the most significant changes in the

market was the growing presence of Columbia/HCA. Columbia entered the market in 1994

as a result of its national merger with HCA. The newly merged entity assumed control

of HCA’s local hospital, Doctors Hospital, and shortly afterward, purchased the largest

medical group in Little Rock. Then, in early 1997, Columbia/HCA announced plans to acquire

Southwest Hospital and increase its market share through additional acquisitions, sparking

concern among local providers about the company’s growing role in the market. At the same

time, national plans such as United HealthCare, Prudential HealthCare and Healthsource,

Inc., were mounting a

competitive challenge to local health plans. The entry of these national plans

intensified premium competition and plans’ marketing campaigns.

t the time of HSC’s first site visit

in late 1996, it was anticipated that the entry

of outsiders would change Little Rock’s health care environment. For the past

several years, a number of national health care companies had come to Little Rock

seeking to build market share. Among

the most significant changes in the

market was the growing presence of Columbia/HCA. Columbia entered the market in 1994

as a result of its national merger with HCA. The newly merged entity assumed control

of HCA’s local hospital, Doctors Hospital, and shortly afterward, purchased the largest

medical group in Little Rock. Then, in early 1997, Columbia/HCA announced plans to acquire

Southwest Hospital and increase its market share through additional acquisitions, sparking

concern among local providers about the company’s growing role in the market. At the same

time, national plans such as United HealthCare, Prudential HealthCare and Healthsource,

Inc., were mounting a

competitive challenge to local health plans. The entry of these national plans

intensified premium competition and plans’ marketing campaigns.

During the past two years, the anticipated threat of outside entrants failed to materialize, as national firms did not capture significant market share from locally based competitors. Many of these firms now have either reduced their presence or retreated from the market altogether. After it failed to garner its anticipated market share and against a backdrop of national Medicare fraud allegations, Columbia/HCA quickly exited the Little Rock market. Both Prudential HealthCare and CIGNA, which purchased Healthsource, appear to be backing away from Little Rock, although they continue to offer products locally, particularly to service their national accounts. These plans reportedly have not been successful in leveraging the oversupply of hospital beds and long lengths of stay needed to generate anticipated profit margins. While respondents note that United HealthCare appears to have remained a viable national plan in the Little Rock area, it is clear that, despite outside pressures, Arkansas Blue Cross Blue Shield has retained its dominant position in the market.

Local Entities Team Up with Other National Firms

![]() eanwhile, local providers and plans

have established affiliations and joint

ventures with other national organizations that have bolstered their market positions.

The Arkansas Heart Hospital,

a joint venture between local cardiologists and the national cardiac care management

company MedCath, Inc., continues to build presence in the market. Discontent with local

hospitals reportedly spurred two groups of cardiologists to approach MedCath and establish

The Arkansas Heart Hospital, which opened in early 1997. Since then, the hospital has lured

an estimated 10 to 20 percent of cardiac surgical volume away from the two major Little Rock

hospital systems. Market observers speculate that the

hospital’s market power ultimately will depend on its ability to secure managed care contracts. To date, however, most

of the hospital’s volume has come from Medicare fee-for-service patients.

eanwhile, local providers and plans

have established affiliations and joint

ventures with other national organizations that have bolstered their market positions.

The Arkansas Heart Hospital,

a joint venture between local cardiologists and the national cardiac care management

company MedCath, Inc., continues to build presence in the market. Discontent with local

hospitals reportedly spurred two groups of cardiologists to approach MedCath and establish

The Arkansas Heart Hospital, which opened in early 1997. Since then, the hospital has lured

an estimated 10 to 20 percent of cardiac surgical volume away from the two major Little Rock

hospital systems. Market observers speculate that the

hospital’s market power ultimately will depend on its ability to secure managed care contracts. To date, however, most

of the hospital’s volume has come from Medicare fee-for-service patients.

In late 1997, St. Vincent Health System, one of Little Rock’s two major hospital systems, aligned with Catholic Health Initiatives, a national not-for-profit health system. This affiliation provided the financial resources that St. Vincent needed to help strengthen its market position, which was described as weakening at the time of the first site visit. The new financial backing allowed St. Vincent to take advantage of Columbia/HCA’s exit and purchase the Columbia/HCA-owned Doctors Hospital and three family clinics. With these acquisitions, St. Vincent was able to expand its service mix and primary care capacity.

Similarly, QualChoice/QCA, a local health plan owned by the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS), improved its market position by aligning with Tenet Healthcare Corporation and other equity partners. Tenet owns four hospitals in other areas of the state and already has ties to the local market through its involvement in NovaSys Health Network, a statewide, provider-governed network. Tenet’s investment gave QualChoice access to the capital it needed to expand its offerings and secure new business in the market.

Powerful Insurer-Hospital Alliance Held in Check

![]() n 1996, the most potent force in

the Little Rock market was the alliance between Arkansas Blue Cross Blue Shield and

Baptist Health System, which joined forces two years earlier in a shared equity

partnership to form what became the area’s most highly subscribed HMO, Health

Advantage. Under the arrangement, Baptist Health provides the

majority of hospital services for Health Advantage members in the Little Rock

area, with the exception of selected

pediatric specialty services provided by Arkansas Children’s Hospital and

services provided by certain hospitals in outlying areas. A similar arrangement

is in place for the Blues’ preferred provider organization (PPO) product. By 1996,

Baptist’s hold on this business gave it a clear advantage over its competitors. This

partnership, and similar arrangements developed with other hospitals around the

state, gave Arkansas Blue Cross Blue Shield added leverage to win managed care

contracts.

n 1996, the most potent force in

the Little Rock market was the alliance between Arkansas Blue Cross Blue Shield and

Baptist Health System, which joined forces two years earlier in a shared equity

partnership to form what became the area’s most highly subscribed HMO, Health

Advantage. Under the arrangement, Baptist Health provides the

majority of hospital services for Health Advantage members in the Little Rock

area, with the exception of selected

pediatric specialty services provided by Arkansas Children’s Hospital and

services provided by certain hospitals in outlying areas. A similar arrangement

is in place for the Blues’ preferred provider organization (PPO) product. By 1996,

Baptist’s hold on this business gave it a clear advantage over its competitors. This

partnership, and similar arrangements developed with other hospitals around the

state, gave Arkansas Blue Cross Blue Shield added leverage to win managed care

contracts.

While the Arkansas Blue Cross Blue Shield/Baptist Health alliance continues to be a dominant force in the market, key local organizations have begun to counter its power through their new associations with national partners. Through its affiliation with Catholic Health Initiative, St. Vincent has improved its financial stability and expanded its presence in the local market. The system bolstered its position by selling its 30 percent equity interest in another national firm, Healthsource. Despite St. Vincent’s stake in the plan and exclusive provider arrangement with it, capitation rates under this contract reportedly proved insufficient to cover its costs. Thus, respondents note that the arrangement turned out to be more of a financial drain for the hospital than a competitive advantage.

St. Vincent has refocused its managed care strategy by pursuing nonexclusive contracts through the provider network NovaSys, which it formed in partnership with Tenet, UAMS and other equity partners in 1996. As an alternative to the Blues/Baptist alliance, NovaSys enabled local providers to join forces with others across the state to offer a substantial statewide network and compete for state employee and public school personnel contracts. NovaSys is now the largest provider network in the state, with 70 hospitals and more than 3,000 physicians. With this reach, the network positions St. Vincent and its partners to compete with Baptist Health and the strong provider network established by Arkansas Blue Cross Blue Shield.

At the same time, Tenet’s parallel investment in the local health plan, QualChoice, appears to be strengthening NovaSys’s tie to the plan, allowing it to bolster its position relative to Arkansas Blue Cross Blue Shield. Although there is no corporate relationship between QualChoice and NovaSys, the plan and provider network appear to be more closely aligned as a result of sharing Tenet as an owner. Since this relationship was established, QualChoice reportedly was able to secure favorable rates with NovaSys providers, allowing QualChoice to underbid competitors for the new exclusive point-of-service (POS) contract for the state employee and school personnel insurance pool. Though other plans offer products to this group-and Arkansas Blue Cross Blue Shield retains the largest portion of this business overall-the ability of QualChoice to secure the POS contract allowed it to more than double its enrollment and begin to make a dent in the Blues’ hold on this business.

Physicians Move to Protect Income

![]() wo years ago, while the majority of

Little Rock physicians practiced in solo

or small single-specialty practices, some had begun to organize into independent

practice associations (IPAs) and larger group practices, marking a shift from

Little Rock’s traditional organization of physician practice. Attempts by health

plans to adjust payment rates through profiling, coupled with the expected growth

of managed care, heightened fear among physicians about loss of income and clinical

autonomy.

wo years ago, while the majority of

Little Rock physicians practiced in solo

or small single-specialty practices, some had begun to organize into independent

practice associations (IPAs) and larger group practices, marking a shift from

Little Rock’s traditional organization of physician practice. Attempts by health

plans to adjust payment rates through profiling, coupled with the expected growth

of managed care, heightened fear among physicians about loss of income and clinical

autonomy.

As a result, Little Rock’s physician market began to consolidate. Columbia/ HCA’s purchase of the area’s largest physician group spurred other hospitals, including St. Vincent and Baptist Health, to acquire primary care physician practices and establish management service organizations (MSOs). Some specialists also moved to organize independently, leading, for example, to the formation of a new large multi-specialty group and a loose affiliation of all of the urologists in the market. Hospital acquisition of primary care practices now appears to be slowing in light of concerns that these purchases have not yielded the necessary return on investment and have not increased referrals.

Meanwhile, specialists have continued to aggregate into larger groups and have found new ways to protect their income and clinical autonomy-primarily by establishing freestanding ambulatory surgery centers. The proliferation of these centers in Little Rock during the past two years has been remarkable. Respondents estimate that six centers are under construction, including those established by the large urologist group, Arkansas Urology Associates, and orthopedic groups such as U.S. Orthopedics and OrthoArkansas. At the same time, there continue to be some additional mergers of single-specialty practices; much of this activity appears to be driven by the effort to secure sufficient volume for these new ventures.

Many specialists view these activities as a hedge against fee reductions and loss of clinical control and as a strategy to increase their leverage with hospitals and health plans. Others in Little Rock characterize these efforts as an attempt by specialists to try to corner the market and retain traditional fee-for-service business for as long as possible. Hospitals view these ventures with considerable concern. Threatened by potential losses in outpatient volume, hospitals have sought joint ventures to establish their own ambulatory surgery centers with physicians. Both St. Vincent and Baptist Health have such arrangements in place. For example, St. Vincent established the North River Surgery Center in partnership with another smaller local hospital, the for-profit management company, HealthSouth, and a group of 40 independent physicians. While the development of ambulatory surgery centers is intended to bring physicians more referrals and ancillary income, the long-term impact of this expansion of capacity and potential fragmentation of the traditional delivery system remains to be seen.

Efforts to Control Costs Are Challenged

![]() t the time of HSC’s first

site visit, some market observers believed that the infusion of outside players

and the growth of managed care would help drive down health care spending and

curtail excess capacity in the market. Since 1996,

however, Little Rock providers have only increased excess capacity. In addition

to the expansion of ambulatory care capacity resulting from the growth of

ambulatory surgery centers, the major hospitals continue to increase inpatient

capacity. Baptist Health and St. Vincent both are building new acute care

facilities in North Little Rock; a new tower at UAMS added 100 inpatient beds; and

the Arkansas Children’s Hospital opened a new 50-bed neonatal unit. These

activities appear to be driven primarily

by hospitals’ interest in expanding their presence in North Little Rock

and the surrounding suburbs to make themselves more accessible and

attractive to the residents and physicians in these areas. Since the repeal of

certificate-of-need regulation for acute care services,

capacity-building continues unchecked, despite the likelihood that these

expansions will drive up costs in the long run.

t the time of HSC’s first

site visit, some market observers believed that the infusion of outside players

and the growth of managed care would help drive down health care spending and

curtail excess capacity in the market. Since 1996,

however, Little Rock providers have only increased excess capacity. In addition

to the expansion of ambulatory care capacity resulting from the growth of

ambulatory surgery centers, the major hospitals continue to increase inpatient

capacity. Baptist Health and St. Vincent both are building new acute care

facilities in North Little Rock; a new tower at UAMS added 100 inpatient beds; and

the Arkansas Children’s Hospital opened a new 50-bed neonatal unit. These

activities appear to be driven primarily

by hospitals’ interest in expanding their presence in North Little Rock

and the surrounding suburbs to make themselves more accessible and

attractive to the residents and physicians in these areas. Since the repeal of

certificate-of-need regulation for acute care services,

capacity-building continues unchecked, despite the likelihood that these

expansions will drive up costs in the long run.

Greater cost control through care management also appears unlikely in the near future. In 1996, all of the major HMOs in the market - and, to a lesser extent, the hospitals - had embarked on physician-profiling initiatives in an attempt to influence clinical practice and control costs. Plans were trying to implement payment methods that linked the level of physician reimbursement to performance indicators. In addition, one plan intended to use information on physician practice patterns to begin dropping high-cost physicians from its local network. Through these initiatives, the HMOs and hospitals hoped to move Little Rock beyond a largely unmanaged fee-for-service system, thereby bringing down health care costs in the market.

By 1998, however, plans had retreated from profiling initiatives in response to physician resistance. According to health plan respondents, physicians objected to linking reimbursement to profiling data and to the quality of the data itself. Implementation was impeded further by limitations of existing data systems.

Several health plans are again cautiously testing the waters with respect to profiling, primarily by focusing on providing physicians with comparative information on practice patterns, without ties to reimbursement. Arkansas Blue Cross Blue Shield is also considering a network-within-a-network strategy that would use profiling data to identify a subset of providers with whom it could develop a lower-priced product. However, the strategy has drawn mixed reactions from physicians.

Issues to Track

![]() ittle Rock appears to remain a

market with few restraints. Although national firms have proved to be important

partners to help local entities gain

leverage, the threat that outside entrants would take over seems to have dissipated.

Managed care arrangements have not grown as expected, but providers

continue to position themselves for

these contracts, while competing for

the fee-for-service revenue that is still available in the market.

ittle Rock appears to remain a

market with few restraints. Although national firms have proved to be important

partners to help local entities gain

leverage, the threat that outside entrants would take over seems to have dissipated.

Managed care arrangements have not grown as expected, but providers

continue to position themselves for

these contracts, while competing for

the fee-for-service revenue that is still available in the market.

As HSC documents change in communities across the United States, key trends that bear watching in Little Rock include:

- Will alliances between local health

care organizations and national firms remain stable and advantageous for local

entities? Will these partnerships continue to allow local plans and providers to

compete against the

powerful Blues/Baptist Health alliance?

- Will plans increase their efforts-through profiling, payment arrangements or

other means-to implement cost controls?

- How will the continuing expansion of capacity affect the cost and quality of care in Little Rock? Will the likelihood of higher health care costs spur purchasers or regulators to pursue more aggressive cost-containment strategies?

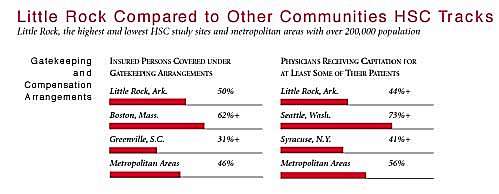

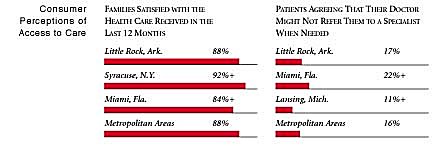

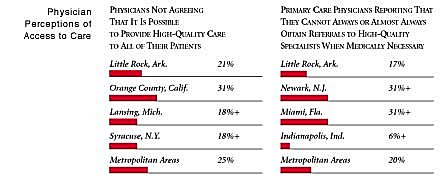

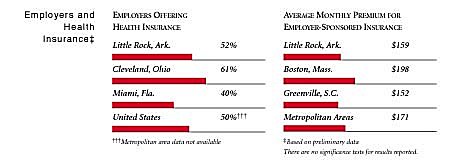

Little Rock Compared to Other Communities HSC Tracks

Little Rock, the highest and lowest HSC study sites and metropolitan areas with over 200,000 population

+Site value is significantly different from the mean for metropolitan areas over 200,000

population.

The information in these graphs comes from the Household, Physician and Employer

Surveys conducted in 1996 and 1997 as part of HSC’s Community Tracking Study. The

margins of error depend on the community and survey question and include +/- 2

percent to +/- 5 percent for the Household Survey, +/-3 percent to +/-9 percent

for the Physician Survey and +/-4 percent to +/-8 percent for the Employer Survey.

Background and Observations

Little Rock Demographics

| Little Rock, Ark. | Metropolitan areas above 200,000 population |

| Population, 19971 | |

| 552,194 | |

| Population Change, 1990-19971 | |

| 7.4% | 6.7% |

| Median Income2 | |

| $24,447 | $26,646 |

| Persons Living in Poverty2 | |

| 14% | 15% |

| Persons Age 65 or Older2 | |

| 12% | 12% |

| Persons with No Health Insurance2 | |

| 16% | 14% |

|

Sources: | |

The Community Tracking Study, the major effort of HSC, tracks changes in the health system in 60 sites that are representative of the nation. Every two years, HSC conducts surveys in all 60 communities and site visits in the following 12 communities:

- Boston, Mass.

- Cleveland, Ohio

- Greenville, S.C.

- Indianapolis, Ind.

- Lansing, Mich.

- Little Rock, Ark.

- Miami, Fla.

- Newark, N.J.

- Orange County, Calif.

- Phoenix, Ariz.

- Seattle, Wash.

- Syracuse, N.Y.