Making Medical Homes Work: Moving from Concept to Practice

HSC Policy Analysis No. 1

December 2008

Paul B. Ginsburg, Myles Maxfield, Ann S. O'Malley, Deborah Peikes, Hoangmai H. Pham

![]() idespread concern about high and rising costs, coupled with increasing evidence that the quality of U.S. health care varies greatly, has put health care reform near the top of the domestic policy agenda. Policy makers face mounting pressure to reform provider payment systems to spur changes in how providers are organized and deliver care.

idespread concern about high and rising costs, coupled with increasing evidence that the quality of U.S. health care varies greatly, has put health care reform near the top of the domestic policy agenda. Policy makers face mounting pressure to reform provider payment systems to spur changes in how providers are organized and deliver care.

In many communities, physician practices, hospitals and other providers are poorly integrated in terms of culture, organization and financing. While these independent arrangements may offer some benefit, such as broadened patient choice, the flip side of independence is fragmentation—across care sites, providers and in clinical decision making for patients. Current payment systems, particularly fee-for-service arrangements, reinforce delivery systems that offer care in silos and reward greater volume but not quality of care. Fee-for-service payment also provides few incentives for providers to invest in improving care for chronic illnesses, which account for a far greater proportion of health care spending than do acute illnesses.

Among the many proposals for payment and delivery system reform under discussion, the medical home model has gained significant momentum in both the public and private sectors. The concept has been promoted by primary care physician societies. And a broad range of insurers and payers—for example, United HealthCare, Aetna, the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association, and Medicaid programs—are developing medical home initiatives. Likewise, Congress has mandated a medical home demonstration in fee-for-service Medicare.

Although medical home definitions vary and continue to evolve, at the heart of a medical home is a physician practice committed to organizing and coordinating care based on patients’ needs and priorities, communicating directly with patients and their families, and integrating care across settings and practitioners. If enough physician practices become medical homes, a critical mass might be attained to transform the care delivery system to provide accessible, continuous, coordinated, patient-centered care to high-need populations—usually considered to be patients with chronic illnesses.

Some advocates ascribe a broader goal to the medical home model—to improve the quality of care, reduce the need for expensive medical services and generate savings for payers. Medical homes are expected to accomplish this goal by changing how physicians practice medicine.

Yet despite the enormous energy and resources invested in the medical home model to date, relatively little has been written about moving from theoretical concept to practical application, particularly on a large scale. What would an effective medical home program look like? And how should it be implemented? Forging ahead with medical home initiatives without such analyses to ground their design and identify potential pitfalls and solutions may result in ineffective programs that alienate patients and/or physicians. That would put at risk not only the resources invested by clinicians and payers/insurers in early initiatives, but also the political viability of the model itself in the long-term as a vehicle for wider health care reform.

The Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC) and Mathematica Policy Research (MPR) are uniquely positioned to address operational issues related to medical homes. Along with conducting independent and collaborative research relevant to medical homes, care coordination, payment policy and the organization of care delivery, HSC and MPR researchers have direct experience with both public- and private-sector medical home initiatives, including leading the design of the Medicare medical home demonstration.

Based on these experiences, we’ve identified four critical operational issues in the implementation of most medical home models that we believe have potential to make or break a successful program: (1) how to qualify physician practices as medical homes; (2) how to match patients to their medical homes; (3) how to engage patients and other providers to work with medical homes in care coordination; and (4) how to pay practices that serve as medical homes. Drawing on published data and our on-the-ground expertise, we hope that these analyses will guide clinicians, payers and policy makers as they attempt to build a solid foundation for successful medical home initiatives. Doing so will improve the chances that the medical home concept can serve as a stepping stone to broader reforms in health care payment and delivery systems.

| CONTENTS |

|

|

|

|

Qualifying a Physician Practice as a Medical Home

Building Medical Homes on a Solid Primary Care Foundation

![]() ublic and private payers are launching patient-centered

medical home (PCMH) experiments as one strategy to improve the quality and coordination

of care, potentially lower costs, and increase financial support to primary

care physicians. These experiments seek to test a medical home concept that

emphasizes the central importance of primary care to an organized and patient-centered

health care system.1,2,3

The medical home concept posits that primary care physicians’ direct and

trusted relationship with patients, coupled with a depth and breadth of clinical

training across body systems, position them to assess an individual’s health

needs and to tailor a comprehensive approach to care across conditions, care

settings and providers.

ublic and private payers are launching patient-centered

medical home (PCMH) experiments as one strategy to improve the quality and coordination

of care, potentially lower costs, and increase financial support to primary

care physicians. These experiments seek to test a medical home concept that

emphasizes the central importance of primary care to an organized and patient-centered

health care system.1,2,3

The medical home concept posits that primary care physicians’ direct and

trusted relationship with patients, coupled with a depth and breadth of clinical

training across body systems, position them to assess an individual’s health

needs and to tailor a comprehensive approach to care across conditions, care

settings and providers.

Not all primary care practices are set up to function as a PCMH. In part, this shortcoming results from inadequate financial support for such activities as care coordination, along with inadequate training of providers on how to work together as a team. In an attempt to remedy this, payers are experimenting with providing additional payment to participating practices that can demonstrate the capabilities of a patient-centered medical home. Most current pilots and demonstrations require practices to “qualify” as a medical home via an objective measurement tool. The tool’s measures, in effect, are a blueprint for practices’ efforts to build medical-home capabilities.

Primary Care and Chronic Care Models

![]() hile there are different views about what makes a physician

practice a medical home, the specialty societies’ joint principles are the widely

accepted starting point for most current demonstrations and pilots.4

The joint principles originate from two distinct conceptual frameworks, the

primary care model1, 2, 5

and the chronic care model,6 each of which was developed

for different purposes.

hile there are different views about what makes a physician

practice a medical home, the specialty societies’ joint principles are the widely

accepted starting point for most current demonstrations and pilots.4

The joint principles originate from two distinct conceptual frameworks, the

primary care model1, 2, 5

and the chronic care model,6 each of which was developed

for different purposes.

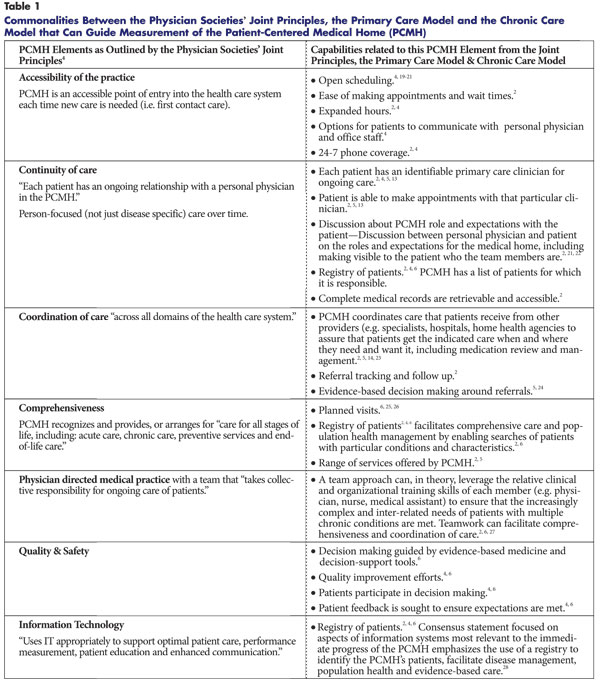

The primary care model1, 2, 5 focuses on all patients in a practice and emphasizes whole-person care over time, rather than single-disease-oriented care. The primary care model identifies four elements as essential to the delivery of high-quality primary care: accessible first contact care, or serving as the entry point to the health care system for the majority of a person’s problems; a continuous relationship with patients over time; comprehensive care that meets or arranges for most of a patient’s health care needs; and coordination of care across a patient’s conditions, providers and settings in consultation with the patient and family.1, 2, 5

The chronic care model focuses on “system changes intended to guide quality improvement and disease management activities” for chronic illness.6 The chronic care model includes six interrelated elements—patient self-management support, clinical information systems, delivery system redesign, decision support, health care organization and community resources. Three aspects of the model in particular—self-management support, delivery system design and decision support—used in combination have improved single chronic condition care, in particular for diabetes.6, 7, 8 The designers of the chronic care model assumed that before implementation “every chronically ill person has a primary care team that organizes and coordinates their care.”6 In other words, the chronic care model is meant to be developed on a “solid platform of primary care.” 6, 9, 10 Consequently, both the primary care and chronic care models suggest that a medical home qualification tool must first capture and measure the four defining primary care elements before emphasizing capabilities to treat individual chronic diseases.

Recognizing the benefits and evidence behind each of the key primary care elements—accessibility, continuity, coordination and comprehensiveness—on patient and population health outcomes, patient and provider satisfaction, and costs, the joint principles require the medical home to provide each.2, 5, 11-18 To the four primary care elements, the physician societies added aspects of the chronic care model—team functioning in a physician-directed practice, quality and safety tools for evidence-based medicine, decision support, performance measurement, quality improvement, enlisting patient feedback and “appropriate” use of information technology.4

Common attributes across the primary care and chronic care models can inform selection of the most relevant measures for a patient-centered medical home qualification tool (see Table 1 for a summary of elements of the two care models as they align with the physician societies’ joint principles). In sum, these conceptual frameworks and the evidence supporting them suggest that a tool to determine whether a practice is a medical home would ideally measure that a practice has in place processes to ensure that care is accessible, continuous, coordinated and comprehensive. Capabilities that could help support these elements include a searchable patient registry, a mutual agreement between the patient and the medical home team on their respective roles and expectations, tools for comprehensive care such as planned visits that include pre- and post-visit planning, the use of care plans when appropriate, and enhanced access via phone and same-day appointment availability. Lastly, because of the time and resource constraints under which primary care practices already operate, it is particularly important that the qualification tool not create an onerous documentation burden for participating practices.

|

Current Qualification Tool

Most medical home demonstrations and pilots are measuring whether a practice is a medical home via the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) Physician Practice Connections-Patient Centered Medical Home tool (PPC-PCMH version 2008).29 The PPC-PCMH is a modification of an earlier NCQA tool, the PPC (Physician Practice Connections) that focused on recognizing practices that use systematic processes and information technology to enhance the quality of care.29 The PPC and the PPC-PCMH are based on the chronic care model6 and have less emphasis on the primary care model’s four elements. While it is difficult to succinctly describe the PPC-PCMH or its scoring algorithm, the tool has nine standards:

- Access and communication;

- Patient tracking and registry functions;

- Care management;

- Patient self-management support;

- Electronic prescribing;

- Test tracking;

- Referral tracking;

- Performance reporting and improvement; and

- Advanced electronic communication.

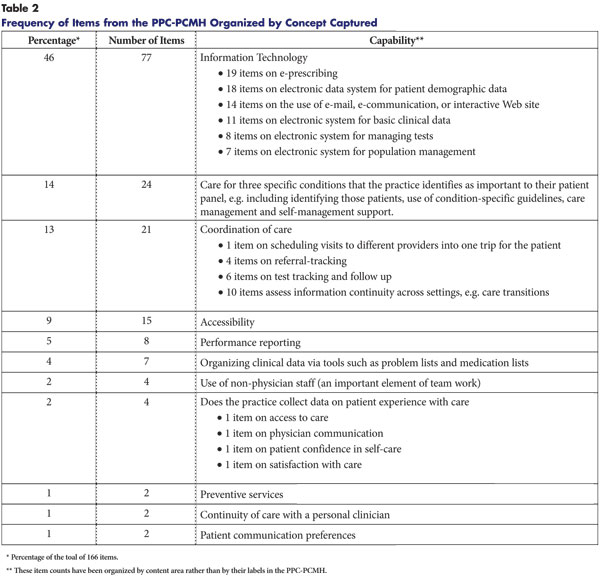

Embedded within the tool’s nine standards are 30 elements containing a total of 166 items, or measures (see Table 2 for a summary of the measures and the capabilities captured). Depending on the score achieved, the PPC-PCMH can qualify a practice at one of three levels of medical-home capabilities (basic, intermediate, advanced). So for example, at Level 1, a practice must pass five of 10 “must-pass” elements. Practices seeking PPC-PCMH recognition complete the Web-based tool and provide documentation to validate responses.29

|

How the Tool Performs in Measuring Medical-Home Capabilities

![]() he PPC-PCMH tool has notable strengths, first of which

is its support from payers, specialty societies and the National Quality Forum.

The tool allows for flexibility in how practices meet some of the requirements.

This is important because procedures for achieving particular capabilities will

likely vary with practice culture, resources and patient-panel characteristics.

In addition, the NCQA tool requires supporting documentation from practices

for those capabilities where validation appears to be necessary to ensure their

presence.2, 30 NCQA’s experience

and infrastructure for fielding and scoring quality measures also are strengths.

Thus, the tool is a good start for developing consistent measurement across

medical home initiatives.

he PPC-PCMH tool has notable strengths, first of which

is its support from payers, specialty societies and the National Quality Forum.

The tool allows for flexibility in how practices meet some of the requirements.

This is important because procedures for achieving particular capabilities will

likely vary with practice culture, resources and patient-panel characteristics.

In addition, the NCQA tool requires supporting documentation from practices

for those capabilities where validation appears to be necessary to ensure their

presence.2, 30 NCQA’s experience

and infrastructure for fielding and scoring quality measures also are strengths.

Thus, the tool is a good start for developing consistent measurement across

medical home initiatives.

However, the current PPC-PCMH may not be ideal for ascertaining medical-home capabilities because it underemphasizes some of the defining primary care elements and overemphasizes issues not specific to a medical home. The tool has a fairly strong emphasis on access and some aspects of coordination, such as referral tracking, but other important aspects of coordination (e.g. between the primary care physician and specialists) are not part of the 2008 version that most pilots plan to use. The tool has only two items on continuity of care and few items on comprehensiveness.

Many of the measures in the PPC-PCMH focus not on primary care, but on such issues as information technology or condition-specific performance reporting. So a practice could potentially score well on the PPC-PCMH without providing patient-centered primary care.

First, the tool places great weight on information technology (IT) capabilities—77 of the 166 measures relate to IT. Information technology clearly has potential to make clinical data available to providers in real time, when it is needed for shared decision making with patients. When an affordable interoperable electronic medical record (EMR) eventually becomes a reality, it will likely be an enormous advance in information continuity across care settings and, thus, potentially foster care coordination.

In the meantime, however, it may be premature to require practices to have more than a searchable patient registry. Many primary care physicians, particularly those in small practices that make up the bulk of the U.S. primary care infrastructure,31 lack the economies of scale that facilitate purchasing and maintaining an EMR and do not want to do so until an affordable and interoperable option is widely available. Moreover, the evidence of commercial EMRs’ effectiveness in primary care practices is mixed. To date, the vast majority of effectiveness studies come from four large institutions with internally developed EMRs.32, 33 Most of the positive outcomes from outpatient studies involve the use of computer-generated, paper-based reminders or registries.32, 33, 34 The presence of an EMR correlates only weakly with clinical quality of care measures. Nevertheless, practices with fully functional EMRs scored the highest on the PPC.35

Two other IT capabilities that are heavily emphasized in the PPC-PCMH, but for which the evidence is mixed, include e-mail communication with patients 36, 37 and e-prescribing.32, 33, 38, 39 Research on e-mail’s effectiveness in patient care is still in its infancy. As of 2006, only 3 percent of physicians used e-mail frequently to communicate with patients.37 While there is momentum in federal policy behind e-prescribing, improved outcomes from e-prescribing have predominantly been demonstrated with computerized physician order entry (CPOE) in the hospital setting. In the primary care setting, results have been more mixed.32, 33, 38-40 The PPC-PCMH’s heavy IT emphasis raises the concern that practices with IT structures may score well without necessarily providing better clinical outcomes or continuous and coordinated care. The large number of IT measures in the NCQA tool could also create barriers to qualification among practices that provide good primary care but don’t necessarily emphasize IT.

Second, the tool requires extensive documentation around single-condition care. The goal of this requirement was to provide practices with the motivation to consider how a systematic approach to work flow and documentation could promote broader changes within a practice. This incremental approach could help practices to systematically address particular chronic conditions and important population-based health issues. The tool allows practices the flexibility to identify what those important conditions are for its patient panel. A caution, however, is that among Americans 65 and older, almost two-thirds have multiple chronic conditions.41, 42 Given this, there is a risk that a measurement approach that overemphasizes adherence to condition-specific guidelines could create incentives to simply treat a patient’s individual condition to achieve benchmarks rather than to provide comprehensive and coordinated care across a patient’s complex health needs.43

Illustrating these risks, a high score on the current PPC-PCMH tool does not guarantee that a practice actually functions as a medical home. One study in predominantly large groups in Minnesota found that particular components (e.g. decision support, clinical information system) of the PPC, a forerunner to the PPC-PCMH were correlated with performance in diabetes care (HgA1c <=8%, LDL <130 mg/dL).44 At the same time, performance on the tool does not appear to correlate with patient experiences with care.35 Thus, while the tool has promise in terms of capturing important elements of diabetes care, a medical home qualification tool should better identify whether patients are experiencing care that is truly patient-centered.

The time required to qualify via the PPC-PCMH tool, both in terms of developing processes to meet the tool’s measures and completion of the application itself, may be a barrier to participation among smaller practices that have fewer resources. After completing a shorter online screening tool that provides practices with an opportunity to estimate where they might fall in relation to the tool’s criteria, the practice can decide whether to move forward with the actual PPC-PCMH. Only anecdotal information is available to date on the 2008 version of the PPC-PCMH. Based on information from the older version, NCQA estimates that the newer PPC-PCMH tool and its documentation take a practice on average between 40 and 80 hours to complete. This does not include time a practice spends developing new processes to address certain capabilities measured by the tool. Several practices report that the older PPC (2004-05) application was time-consuming, taking 80 to 100 hours to complete.45 Given that practices with five or fewer physicians constitute 95 percent of office-based medical practices,31 such time and resource considerations could pose significant barriers to participation among the very practices medical home initiatives are targeting.

Next Steps

![]() ne approach to modifying the PPC-PCMH tool would be to focus initially on measures that capture the key primary care elements, are supported by evidence, and that experience suggests are feasible or have the strongest face validity with practitioners and patients. If certain measures require a good deal of time and documentation from a practice, then there should be strong evidence that they lead to improved patient outcomes.

ne approach to modifying the PPC-PCMH tool would be to focus initially on measures that capture the key primary care elements, are supported by evidence, and that experience suggests are feasible or have the strongest face validity with practitioners and patients. If certain measures require a good deal of time and documentation from a practice, then there should be strong evidence that they lead to improved patient outcomes.

The burden on practices to complete the PPC-PCMH documentation could be reduced by decreasing the number of IT items, particularly those with inconclusive data on effectiveness. Practices that have an EMR should get credit for their efforts, but this can be ascertained with fewer IT measures. Existing data do support keeping a measure of whether a practice has an electronic patient registry, including a list of patients for whom a practice serves as a medical home and that can be used to identify patients needing preventive services and chronic condition management.2, 6, 28

At this point, the PPC-PCMH might be viewed as a starting point for developing a future tool that more comprehensively captures the four primary care elements. Validated measures for these primary care elements exist,46, 47 and selected domains from validated provider surveys could be incorporated into the PPC-PCMH.46 For example, in addition to the tool’s two current measures of continuity of care—scheduling each patient with a personal clinician and visits with the assigned personal clinician—validated items on continuity could be added, such as how long on average patients stay with the practice and what percentage of patients use the practice for most of their non-emergency sick and well care needs.

The tool could include measures on processes to improve communication between the medical home and specialists related to referrals and consultations. With respect to comprehensiveness, a practice could check off services provided, ranging from preventive, acute and chronic care to basic procedures that can be done in the office setting with a focus on those known to be cost-effective and of sufficient need in the population, such as immunizations, family planning and pulmonary function tests.2

Validation that the medical home is indeed patient-centered could be enhanced by the inclusion of patient feedback in a qualification tool. While most demonstrations and pilots will delay enlisting patient feedback until the evaluation phase (rather than doing so in the qualification phase), confirmation of the presence of particular PCMH elements during the qualification phase could be assisted by incorporating patient input using validated measures.46, 47

Recognizing many of these concerns, the physician specialty societies endorsed the PPC-PCMH for testing purposes only. NCQA is working to incorporate stakeholder input into future versions of the tool, including measures of coordination between the primary care physician and specialists and an important measure on mutual acknowledgement of the partnership between the patient and the medical home. Unfortunately, these revisions are not likely to be incorporated in time for the tool that will be used in the qualification phase of most pilots. The reality of current medical home initiatives is that payers want to see documentation of improved capabilities from providers if they are going to increase reimbursement for medical home services. In an effort to be responsive to that request, the medical home qualification tool train has, perhaps, prematurely left the station.

Past experience with performance measurement linked to payment suggests that “we will get what we measure.” Both the primary care and chronic care models suggest that the qualification of practices as medical homes should be based on the conceptual underpinnings of primary care. Measures in a medical home qualification tool, therefore, should capture the structures and processes that ensure accessibility, continuity, coordination and comprehensiveness. Additional capabilities that could help deliver these elements and enhance chronic care provision include a patient registry, mutual acknowledgement between the patient and the medical home physician on their respective roles and expectations, 24-7 phone access, some same-day appointments, team-based care, and the use of planned care visits.

At this critical turning point for the nation’s fragile and underfunded primary care infrastructure, a medical home qualification tool that insufficiently emphasizes key primary care elements risks excluding physician practices that actually deliver patient-centered primary care as medical homes and including those that don’t. Moreover, an overly burdensome tool with large documentation requirements for structures that ultimately may not be associated with improved clinical outcomes runs the risk of distracting physicians from developing the practice capabilities that can truly improve patient care.

Back to TopMatching Patients to Medical Homes: Ensuring Patient and Physician Choice

By Deborah Peikes, Hoahngmai H. Pham, Ann S. O’Malley and Myles Maxfield

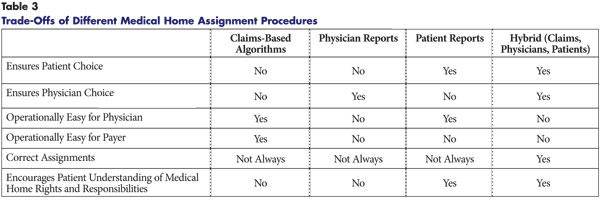

For medical homes to achieve their potential to improve care, payers must link each eligible patient to a medical home practice in a way that ensures transparency, clinical face validity and fairness for physicians. Equally important are adequate choice and awareness of the medical home model for patients and operational feasibility for payers that must determine which physician practices are eligible for enhanced payments. The approach the payer uses to assign, or attribute, patients to medical homes will ultimately influence how successfully medical home initiatives can engage patients and physicians.

Why Patient Assignment Matters, Or It Takes Three to Tango

![]() hysician practices acting as medical homes need to know which patients they are responsible for so the practices can coordinate those patients’ care. If physicians can clearly identify the patients they are responsible for, they can more accurately predict the additional revenue they can expect for acting as a medical home. More accurate revenue prediction in turn allows practices to make informed decisions about whether they want to become a medical home and what additional staff or infrastructure, such as information technology, they can afford to purchase. Finally, giving physicians some choice about which patients they will form medical home relationships with rather than having this dictated by a payer will enhance physician buy in.

hysician practices acting as medical homes need to know which patients they are responsible for so the practices can coordinate those patients’ care. If physicians can clearly identify the patients they are responsible for, they can more accurately predict the additional revenue they can expect for acting as a medical home. More accurate revenue prediction in turn allows practices to make informed decisions about whether they want to become a medical home and what additional staff or infrastructure, such as information technology, they can afford to purchase. Finally, giving physicians some choice about which patients they will form medical home relationships with rather than having this dictated by a payer will enhance physician buy in.

Patients need to know which practice serves as their medical home so they know who to count on to coordinate and manage their overall care. In addition, patients need to be aware of what the medical home will provide if they are to work closely with the medical home and change the way they use care. To be sure, a patient can garner some benefit from practice transformations resulting from their physician’s practice becoming a medical home—such as ensuring that abnormal lab results are tracked—without knowing about the medical home model. Ideally, however, the medical home will help patients decide when to see a specialist, select a specialist that will both serve the patient’s clinical needs and coordinate with the medical home physician, and achieve smooth transitions after a hospital discharge.

The current fee-for-service payment system lacks incentives for primary care physicians to consistently play an active role in integrating and coordinating care. Without a conversation explaining the new medical home model of care, many patients will continue to use care outside of the medical home without telling their medical home physician. If physicians are unaware of patients’ self-referrals to specialists, or emergency room and hospital use, they cannot help patients coordinate their care. Similarly, if medical homes provide expanded access, this should also be explained to patients so they do not simply use the emergency room or seek out another primary care physician for problems that can be addressed in the medical home practice.

Evidence suggests that educating patients about the roles and responsibilities of both the medical home physician and the patient can help patients transform the way they use care. Indeed, the British Columbia Primary Care Demonstration found that patients’ use of specialty, emergency room and primary care delivered by other physicians declined only after the program changed the registration process to require that physicians educate patients about the benefits of continuity of care with the primary care physician, as well as providing extended hours.

The final reason patients should be informed of the medical home is to address potential privacy concerns. If patients are not informed, they may be alarmed to find out that payers are sharing confidential information with the medical home physician about their use of emergency room, hospital and specialist care.

Payers, typically insurers, need to link patients to specific physicians for three reasons. First, since most insurers in part use capitated payments, or per-patient, per-month fees, to compensate physicians for providing medical home services, insurers need to know which patients belong to which physicians so that payment goes to the correct physicians. Second, some insurers provide feedback data on quality and utilization for individual patients or the entire patient panel to physicians as part of their medical home initiatives. Finally, insurers need to know which patients belong with which physicians when they evaluate the effectiveness of the medical home.

Payers can link patients to physicians using four general approaches:

- apply claims-based algorithms;

- ask physicians to identify patients;

- ask patients to identify physicians; or

- employ hybrids of these three approaches.

Each of the approaches has different strengths and weaknesses on six important dimensions: patient choice, physician choice, ease for physician, ease for insurer, correct assignments and encouraging patient understanding of medical home rights and responsibilities (see Table 3).

|

Claims-Only Approach Common but Prone to Errors

![]() he most commonly used approach to linking patients to physicians

in commercial insurers’ medical home pilots relies on claims-based algorithms.

Such algorithms typically search historical claims for the physician billing

for the most recent claims with an evaluation and management (E&M) code or pharmacy

claim, or the largest share of E&M visits for the patient.48

Claims-based approaches are expeditious because the insurer avoids the costs

of collecting information from patients and physicians.

he most commonly used approach to linking patients to physicians

in commercial insurers’ medical home pilots relies on claims-based algorithms.

Such algorithms typically search historical claims for the physician billing

for the most recent claims with an evaluation and management (E&M) code or pharmacy

claim, or the largest share of E&M visits for the patient.48

Claims-based approaches are expeditious because the insurer avoids the costs

of collecting information from patients and physicians.

An approach that relies exclusively on claims is operationally easy for both insurers, who simply review historical claims data, and physicians, who do not participate in any way. However, by excluding physician and patient input, this approach does not allow either to select the person with whom they perceive they have a medical home relationship. Moreover, automatic assignment may interfere with existing patient-physician relationships and risk alienating both parties. Even if claims could get the assignment correct, the success of the medical home intervention depends on educating patients about the new services medical homes are providing and how to use care in a way that facilitates efficiency and coordination. Without involving patients, this opportunity is lost.

Perhaps most importantly, while the efficiency of using historical claims data is tempting from an operational perspective, claims can be inaccurate and may not reflect clinical realities. Because many patients see multiple physicians, claims algorithms cannot always indentify the correct provider. For example, in a given year, Medicare beneficiaries see a median of two primary care providers and five specialists working in four different practices.49 The Medicare Health Support (MHS) study examined how often a group of physicians identified via a claims algorithm actually included the patient’s self-reported primary physician for heart disease. While the algorithm identified on average five doctors per beneficiary that might be the personal physician, it failed to include the primary physician as identified by 17 percent of patients.50

Another illustration of the inaccuracy of claims-based algorithms comes from the seeming instability of care relationships suggested by claims data, which may not be consistent with patient self-reports. The Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey indicates that patients’ care relationships are more stable than the claims-based algorithm would suggest, as 70 percent of beneficiaries reported having the same physician as their usual provider for at least three years; the analogous figure would be less than 40 percent based on claims assignment.49

Anecdotal evidence suggests patients with other types of insurance also see multiple primary care practices. For example, one state Medicaid program found that half of all patients whose claims suggested they saw a large primary care practice as their medical home—they had one or more well-child visits or two or more sick visits with the practice in the prior year—also had visits with other nearby practices. United Healthcare’s analysis of claims data convinced the company to supplement claims information with patient and physician input. The analysis used the prior 18 months of claims to identify the likely medical home practice of commercially insured patients aged 18 to 64. A year later, claims data suggested that 72 percent of the patients with a medical home the year before who still had coverage with United had the same medical home practice, 16 percent had moved to another practice, and 12 percent did not use a primary care practice.51 Claims data alone cannot answer whether these patients truly changed the practice they consider to be their medical home.

Another problem with most current claims-based approaches is that they do not address patients who lack a primary care physician, or the “medically homeless.” One study found that in a one-year period, 15 percent of all Medicare beneficiaries saw only specialists without seeing any primary care doctors, and 6 percent had no E&M visits with any type of doctor.49 Another study reported that more than one-third of working-age adults did not have an accessible primary care provider, and half of children did not have a medical home.52 Approaches based purely on claims would not be able to assign these patients.

Physicians May Be Unaware of Other Providers

![]() n approach that asks physicians to identify which patients to assign to their practice still requires insurers to reconcile each physician’s patient list to ensure the patients are eligible for coverage and have not been identified by another physician. While physicians would have input into which patients they would like to serve, in many cases, they may not be aware of other physicians that their patients see.

n approach that asks physicians to identify which patients to assign to their practice still requires insurers to reconcile each physician’s patient list to ensure the patients are eligible for coverage and have not been identified by another physician. While physicians would have input into which patients they would like to serve, in many cases, they may not be aware of other physicians that their patients see.

Thus, an approach that relies on physician input without patient input may not always generate correct assignments. And like claims-only approaches, physician-driven approaches would not assist patients in receiving adequate information about the new medical home services.

Patient Reports Operationally Challenging

![]() urning to a patient-focused approach, where patients would

be asked to submit the name of their medical home, the burden on insurers to

collect this information from patients would be high. People don’t always turn

in their forms. For example, often only one-third to one-half of people respond

to social science surveys without substantial effort to collect their responses.

Even when money is at stake, not all people file the necessary forms. Only 80

percent to 86 percent of tax filers eligible for the earned income tax credit

actually claim the credit.53

urning to a patient-focused approach, where patients would

be asked to submit the name of their medical home, the burden on insurers to

collect this information from patients would be high. People don’t always turn

in their forms. For example, often only one-third to one-half of people respond

to social science surveys without substantial effort to collect their responses.

Even when money is at stake, not all people file the necessary forms. Only 80

percent to 86 percent of tax filers eligible for the earned income tax credit

actually claim the credit.53

The patient-based approach has three strengths. First, there is no operational burden on physicians. Second, the assignments will be correct from the patient perspective. Third, because insurers will need to inform patients about the medical home concept when their input is solicited, insurers likely would inform patients of their medical home rights and responsibilities. However, the physician’s perception of who their core patients are may vary from the patient’s perspective.

A Hybrid Approach Can Help Build Medical Home Relationships

![]() hybrid approach that combines features of the claims-based, physician-driven and patient-driven approaches would best help build medical home relationships while honoring existing patient-physician relationships. For example, insurers could send practices a list of their potential patients (e.g., those who claims indicate they saw the physician one or more times in the prior two years). The physicians would then be expected to obtain the patient’s consent to be matched to their practice, and the physician could explain medical home features to the patients. This approach also ensures that patients can decline if they prefer another medical home.

hybrid approach that combines features of the claims-based, physician-driven and patient-driven approaches would best help build medical home relationships while honoring existing patient-physician relationships. For example, insurers could send practices a list of their potential patients (e.g., those who claims indicate they saw the physician one or more times in the prior two years). The physicians would then be expected to obtain the patient’s consent to be matched to their practice, and the physician could explain medical home features to the patients. This approach also ensures that patients can decline if they prefer another medical home.

Insurers could send patients who had not seen a physician in the prior two years a list of medical homes in their area that are accepting new patients and ask patients to select one, or opt in. While insurers might not wish to simply assign patients to a practice and give them the opportunity to change that assignment—an opt-out approach—there may be a role for such an approach for patients who do not voluntarily select a medical home. The insurer could assign those patients to a practice and notify both the practice and patient of the assignment and the patient’s ability to change to another medical home if desired. Seeking patient input, and only assigning patients if they do not provide it, decreases the burden for the insurer, while still maximizing patient and physician choice.

The insurer could also require a formal, bilateral acknowledgment between the medical home physician and the patient that explains the respective roles of the medical home and the patient. Patients would retain the right to change their medical home if they are not satisfied with their care.

Accurate Assignment Matters

![]() ccurate and meaningful linkages between the patient and the medical home physician

are critical and require the input of physicians and patients. Having a process

in place that requires patients to participate actively is pivotal to the potential

of medical homes to transform patterns of care.

ccurate and meaningful linkages between the patient and the medical home physician

are critical and require the input of physicians and patients. Having a process

in place that requires patients to participate actively is pivotal to the potential

of medical homes to transform patterns of care.

An approach that balances the needs and preferences of patients, physician practices and payers carries four benefits. First, such an approach helps obtain patient buy in to understand and use new medical home services effectively. Second, physicians will have clear responsibility for individual patients and be better able to coordinate care for those patients. Third, insurers can direct payment and provide information on service use and prevention or treatment needs to each physician for the appropriate patients. Finally, the most accurate approaches to assignment will facilitate rigorous evaluations of the medical home model.

Back to TopMedical Homes: The Information Exchange Challenge

Myles Maxfield, Hoangmai H. Pham and Deborah Peikes

The potential of medical homes to improve quality and reduce costs by improving coordination of care across providers, care settings and clinical conditions will be limited without effective mechanisms for exchanging clinical information with patients and providers outside of the medical home. An explicit agreement between the medical home and the patient detailing the roles and responsibilities of both could assist with the exchange of information. Exchanging information with specialists may not be feasible without some form of electronic exchange or incentives for specialists to participate.

![]() edical home initiatives typically have two overarching goals—to reduce costs and improve the quality of care. Medical homes are expected to reduce costs directly by avoiding redundant or unneeded tests, imaging, procedures and medications, hereafter generically called unnecessary services. These reductions are expected to be large enough to offset any increased spending on medical home services. By maintaining comprehensive clinical information on patients, medical homes can avoid unnecessary services in three ways: 1) using the results of tests, imaging and services ordered by other providers; 2) advising patients who seek care from another provider whether that care is needed; and 3) increasing the delivery of primary and secondary preventive care.

edical home initiatives typically have two overarching goals—to reduce costs and improve the quality of care. Medical homes are expected to reduce costs directly by avoiding redundant or unneeded tests, imaging, procedures and medications, hereafter generically called unnecessary services. These reductions are expected to be large enough to offset any increased spending on medical home services. By maintaining comprehensive clinical information on patients, medical homes can avoid unnecessary services in three ways: 1) using the results of tests, imaging and services ordered by other providers; 2) advising patients who seek care from another provider whether that care is needed; and 3) increasing the delivery of primary and secondary preventive care.

The second overarching goal of medical home programs is improving the quality of care by maintaining comprehensive clinical information on the care patients receive from other providers, providing a sounder basis for the medical home physician’s diagnoses and treatment decisions. In addition, use of evidence-based guidelines and registries can help medical homes ensure patients receive recommended care. Improved quality of care also may reduce health care costs by avoiding preventable hospitalizations, complications, medical errors and unnecessarily long episodes of care.

Coordinating care across providers is one critical way to reduce overuse of services. The medical home ideally will help patients use appropriate specialists and coordinate the testing and treatment that all providers deliver. But whether medical homes can achieve this goal depends on the behavior of patients and other providers—behavior that medical homes cannot completely control. Medical home physicians rely on patients to report plans to see other providers, including specialists. Without such knowledge, medical home physicians cannot make appropriate decisions to instead provide the care themselves, steer the patient to a high-quality specialist or determine if another type of specialist would be more appropriate.

Unfortunately, there is a risk that patients may not share this information with the medical home. Fee-for-service payment systems provide few incentives, penalties or restrictions on patients’ use of other providers, and some patients may view efforts to coordinate with the medical home physician as restrictive and time-consuming.

Specialists must in turn share information about their clinical findings, prescribed medications and care plan with the medical home, either directly or through the patient, so the medical home can ensure that the patient’s overall care is consistent and integrated. But under neither fee-for-service nor current medical home models do specialists receive additional compensation or other incentives for communicating with the medical home or patients. While some might argue that existing standards of care and payment rates already include expectations for such communication, the reality is that it often does not occur.

Medical Home Information Exchange

![]() ffective information exchange between the medical home and the patient relies

on an agreement between the medical home and the patient. Under such an agreement,

patients agree to tell the medical home when they wish to see another primary

care physician or specialist and why. In return, the medical home agrees to

oversee the entirety of patients’ care, including advising patients whether

or not to seek care from another practitioner. If patients are unwilling to

share complete information on the care they receive, or wish to receive, from

other providers, the medical home will not be able to comprehensively manage

patient care. Such a breakdown in the exchange of information between the medical

home and patient would leave the patient’s care as fragmented and inefficient

as under current fee-for-service arrangements.

ffective information exchange between the medical home and the patient relies

on an agreement between the medical home and the patient. Under such an agreement,

patients agree to tell the medical home when they wish to see another primary

care physician or specialist and why. In return, the medical home agrees to

oversee the entirety of patients’ care, including advising patients whether

or not to seek care from another practitioner. If patients are unwilling to

share complete information on the care they receive, or wish to receive, from

other providers, the medical home will not be able to comprehensively manage

patient care. Such a breakdown in the exchange of information between the medical

home and patient would leave the patient’s care as fragmented and inefficient

as under current fee-for-service arrangements.

The exchange of clinical information between the medical home and patients’ other providers—specialists, other primary care physicians, hospitals, post-acute care facilities, nursing homes—is equally essential to the medical home model.

Patient Challenges

![]() here are two major challenges to exchanging clinical information between the

medical home and patients. The first is that many patients in fee-for-service

systems may not want to put all their information eggs in one medical home basket.

Specifically, many patients, and especially many Medicare beneficiaries with

chronic conditions, see many practitioners, including multiple primary care

physicians. Some patients believe that doing so offers the advantages of multiple

perspectives on the best treatment approach. These patients may not want to

place all their trust in the hands of a single medical home provider in the

belief that “two physician heads are better than one.”

here are two major challenges to exchanging clinical information between the

medical home and patients. The first is that many patients in fee-for-service

systems may not want to put all their information eggs in one medical home basket.

Specifically, many patients, and especially many Medicare beneficiaries with

chronic conditions, see many practitioners, including multiple primary care

physicians. Some patients believe that doing so offers the advantages of multiple

perspectives on the best treatment approach. These patients may not want to

place all their trust in the hands of a single medical home provider in the

belief that “two physician heads are better than one.”

The second major challenge is that some patients may fear their medical homes will function as a gatekeeper to control access to other providers. While the medical home model tries to avoid the mandatory gatekeeper model used by some managed care organizations, medical homes are likely to have a “soft gatekeeper” function. One of the most important mechanisms for medical homes to achieve cost savings is for the medical home to identify potentially redundant tests and services before they occur and counsel patients to avoid redundant services. While some patients may dislike this oversight, others may simply not take the time to circle back and inform their medical home about care they plan to receive, or have received, elsewhere.

Specialist Challenges

![]() s challenging as the medical home-patient exchange of information is, the

medical home-specialist exchange may be more so. The primary challenge in exchanging

information with other providers is that the number of other providers can be

large. One study found that the typical primary care physician shares his or

her Medicare patients with 229 other physicians working in 117 other practices.54

s challenging as the medical home-patient exchange of information is, the

medical home-specialist exchange may be more so. The primary challenge in exchanging

information with other providers is that the number of other providers can be

large. One study found that the typical primary care physician shares his or

her Medicare patients with 229 other physicians working in 117 other practices.54

In most communities, different physician practices operate autonomously of one another, with little integration in terms of common culture, administrative procedures, financing or information systems. Many medical homes may find it practically infeasible to negotiate “service agreements” with all providers seeing their patients to lay out common expectations about how each party will share clinical information. Even if service agreements were negotiated with all other providers, many medical homes would find it infeasible to exchange information with all providers seeing all of the medical home’s patients. Without some form of electronic information exchange among providers beyond fax machines, implementing information flows among networks of this magnitude may not be practical for many practices.

Second, medical homes cannot establish service agreements with every other provider because some of those encounters, such as those in emergency departments or during hospital admissions, cannot be easily anticipated. Thus, a related issue for coordinating care with outside providers is how to improve information flow so that medical homes know when their patients use emergency departments or are hospitalized. With more complete information on incidental care encounters, medical homes would be better able to educate patients about potential alternatives for care, provide relevant clinical history to emergency and inpatient providers, assist in communicating with patients’ families, and help patients understand hospital discharge instructions and coordinate transitional care.

Third, many specialists may not see the value of entering into service agreements with medical homes. Specifically, payers typically pay a fee to the medical home that includes the time and equipment devoted to the information exchange, but specialists are not paid directly. If the specialist is practicing in a geographic area containing many medical homes, the costs of exchanging information on many patients with many medical homes may be substantial. In theory, the medical home could compensate specialists for the time and equipment used in the information exchange by sharing medical home fees with specialists. Such an arrangement may require modification to law and regulation pertaining to provider fee-splitting. In practice, many sponsors of medical home initiatives do not include the full cost of exchanging information with other providers in medical home fees. In such instances, the medical home is unlikely to share fees with specialists.

Overcoming Challenges

![]() everal approaches can mitigate the challenges of the medical home-patient

information exchange. The first is to make the agreement between the medical

home and the patient as explicit and formal as possible. This means the agreement

should be written, and the medical home should discuss the agreement with the

patient, ideally in person. The agreement should describe the responsibilities

of, and benefits to, the patient and the medical home. Patients agree to share

information on all aspects of their care with the medical home provider and

to consider the medical home physician’s advice seriously, even when it

pertains to care provided by a different physician. In return, the medical home

offers the patient better coordinated care and a more satisfactory patient experience.

Both parties should sign the agreement.

everal approaches can mitigate the challenges of the medical home-patient

information exchange. The first is to make the agreement between the medical

home and the patient as explicit and formal as possible. This means the agreement

should be written, and the medical home should discuss the agreement with the

patient, ideally in person. The agreement should describe the responsibilities

of, and benefits to, the patient and the medical home. Patients agree to share

information on all aspects of their care with the medical home provider and

to consider the medical home physician’s advice seriously, even when it

pertains to care provided by a different physician. In return, the medical home

offers the patient better coordinated care and a more satisfactory patient experience.

Both parties should sign the agreement.

A second approach is for the medical home program to exclude patients who are unwilling to enter into such an agreement. The medical home should attempt to persuade the patient to join the medical home program, but failing that, the medical home and program sponsors should recognize that the medical home model may not be well suited to all patients.

Turning to the medical home-specialist information exchange, the less expensive it is to exchange a particular type of information, the more feasible it will be for medical homes to exchange information with large numbers of specialists. One way to minimize the cost of information exchange is for medical home programs to focus on practices that already participate in a network of providers, such as an integrated service delivery network (ISDN), health information exchange (HIE) or regional health information organization (RHIO). For example, such networks can include information exchanges with local hospitals through electronic physician portals55 that can push information to the medical home practice when a patient is evaluated at a hospital. Such an approach was used successfully with several disease management providers in recent Medicare demonstrations. Such networks minimize the cost of setting information exchange agreements with specialists, as well as minimize the transaction cost of exchanging clinical information.

A second approach specific to ambulatory care physicians is for payers to require specialists to enter into service agreements with medical homes as a condition of inclusion in their plan network. Third, payers could leverage other financial incentives they may already be offering providers to use electronic information systems. For example, Medicare could combine the financial incentives in its electronic health record (EHR) demonstration with the Medicare medical home demonstration. The combined incentive may encourage more practices to invest in EHR technology, which would in turn reduce the transaction cost of the information exchange. For this strategy to be effective, payers would have to require interoperable EHR systems.

Fourth, payers could use claims data to provide feedback to the medical home on the patient’s health care from other providers. Information on hospital admissions, emergency room use and the need for preventive services would be particularly useful. Clearly this strategy raises privacy concerns, but the agreement between the medical home and the patient could include the patient’s informed consent for the release of such information to the medical home.

Fostering Care Delivery Changes

![]() he medical home model can serve as an impetus for increasing primary care

physicians’ responsibility and authority to coordinate the care of their

patients, as well as foster greater patient self-management of medical conditions.

Ultimately, piecemeal incentives will likely have limited ability to ensure

effective coordination of care across multiple providers that remain unaffiliated

and poorly integrated in their management, culture and financing.

he medical home model can serve as an impetus for increasing primary care

physicians’ responsibility and authority to coordinate the care of their

patients, as well as foster greater patient self-management of medical conditions.

Ultimately, piecemeal incentives will likely have limited ability to ensure

effective coordination of care across multiple providers that remain unaffiliated

and poorly integrated in their management, culture and financing.

Policy makers might consider an improved medical home model as a bridge to broader

reforms of the organization of delivery systems, in which they encourage the

“virtual” networks defined by service agreements to gradually become

actual networks of affiliated providers. Favorable payment systems that focus

on provider organizations that are integrated can create incentives for medical

practices—and health care markets—to evolve toward greater cohesion

through enlarging existing practices, mergers among practices or practices and

hospital systems, or other creative arrangements. The medical home model is

unlikely to result in sustainable, meaningful improvements in care coordination

and outcomes without confronting and addressing these underlying issues in the

organization of care delivery.

Back to Top

Paying for Medical Homes: A Calculated Risk

By Hoangmai H. Pham, Deborah Peikes and Paul B. Ginsburg

The resurgence in interest among policy makers in the medical home concept stems from goals of improving quality and reducing health care costs. Another driver of recent advocacy for the model is the search for vehicles to increase financial support for primary care physicians, whose services are widely acknowledged to be undercompensated in current fee-for-service payment systems. Moreover, existing fee-for-service payment systems typically do not pay for important activities that primary care physicians perform, such as care coordination and patient education.

Partial Capitation Payment Dominates Medical Home Pilots and Demonstrations

![]() ayment approaches for medical homes under current fee-for-service payment systems essentially focus on additional payment for currently uncovered services. But the signal challenge is that payers have limited data both on what these uncovered services are in current practice and what the ideal array of services should be—that is, services that dependably result in high-quality, efficient patient care.

ayment approaches for medical homes under current fee-for-service payment systems essentially focus on additional payment for currently uncovered services. But the signal challenge is that payers have limited data both on what these uncovered services are in current practice and what the ideal array of services should be—that is, services that dependably result in high-quality, efficient patient care.

Payers recognize that medical home services, such as care coordination, are difficult to itemize, may occur outside face-to-face patient visits, and can legitimately vary in type and intensity across different patients or over time for a given patient. Paying for medical home services effectively requires some sort of capitation, or fixed per-patient fees. Most payers sponsoring medical home demonstrations or pilots offer additional payment in the form of partial capitation—a single per-patient, per-month or per-practice, per-year fee that is prospectively calculated.

Across public- and private-sector medical home initiatives, it is also clear that payers are more focused on paying for the processes that medical homes engage in than on the outcomes of those processes. Generally, if medical home initiatives incorporate any variation in payment levels, they tend to link payments to levels of medical-home capability. Frequently they do not consider patients’ disease burden or physicians’ performance on standardized quality measures. Although a few medical home initiatives—for example, those sponsored by the state of Vermont and the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association—recommend incorporating bonuses tied to physicians’ performance on clinical quality or patient satisfaction measures, most payers are taking a wait-and-see approach on bonuses. Even fewer payers are considering payment adjustments based on patients’ illness burden, a posture that makes it difficult to adapt payment levels from one program to another if the programs serve markedly different patient populations—for example, working-age, healthy commercially insured patients vs. sicker Medicare patients. One major exception is the Medicare medical home demonstration (MMHD), which will adjust payment rates based on illness severity.

The Constraint of Budget Neutrality

![]() he most straightforward approach to setting capitated payments would be to

first identify the services to be covered—those payers deem effective and

currently not reimbursed—and then estimate their unit costs and frequency

of delivery to the typical patient. Summing the product of unit costs and service

frequency for a given time period would yield a per-capita amount, such as a

monthly care management fee. However, calibrating even limited capitated payments

proves a thorny endeavor, because payers currently place a high priority on

budget neutrality. The hope is that potential savings from delivery of medical

home services, such as reduced hospitalizations from improved care coordination,

will offset any additional payments to physician practices for serving as medical

homes.

he most straightforward approach to setting capitated payments would be to

first identify the services to be covered—those payers deem effective and

currently not reimbursed—and then estimate their unit costs and frequency

of delivery to the typical patient. Summing the product of unit costs and service

frequency for a given time period would yield a per-capita amount, such as a

monthly care management fee. However, calibrating even limited capitated payments

proves a thorny endeavor, because payers currently place a high priority on

budget neutrality. The hope is that potential savings from delivery of medical

home services, such as reduced hospitalizations from improved care coordination,

will offset any additional payments to physician practices for serving as medical

homes.

But there is so little experience with medical homes that, as yet, there is no certainty that additional services will actually increase efficiency through lower costs and/or improved quality. This uncertainty makes it difficult to set payment levels that will achieve spending neutrality and to determine whether such levels will be sufficient to underwrite the costs of the activities that payers expect medical homes to perform.

Setting payments is particularly challenging in the context of demonstrations and pilots. Physicians naturally are concerned about how they will fare financially in a program of limited duration. They have reason to worry about payers’ long-term commitment to pay for medical-home capabilities and the amount of time practices would have to amortize costs incurred to become medical homes. And physicians’ perception of the adequacy of payments arguably carries more weight for medical home services than other services, because physicians have to be willing to participate if payers are to establish and sustain this new model.

Lastly, not all patients need the same amount of care coordination and not all medical homes offer the same services—the “typical” unit of medical home care is more difficult to define than that of more discrete services, such as a colonoscopy. For example, one medical home practice might attempt to improve coordination by implementing electronic data exchange with other providers—a resource-intensive strategy—while another practice might opt instead to implement team meetings for particular patients—a far less expensive strategy. Because most medical home initiatives allow physicians to choose different qualifying capabilities, fixed payment levels may not match the actual costs of a particular medical-home capability.

So physicians may expect payments to reflect differences both in disease burden and medical-home capabilities, adding layers of administrative complexity. Unfortunately, the lack of sound cost data to provide different medical home services to different types of patients leaves payers and physicians dependent on educated guesswork for setting cost-based prices.

Given the complexity of setting medical home payment levels, it is no wonder that payment levels range as broadly as they do across different programs—from an expected $20,000 to $30,000 per practice, per year in Vermont to $35,000 to $85,000 per full-time physician per year in Philadelphia. Fees in the Medicare demonstration could total $104,232 or $133,386 per year for the typical primary care physician.56

Calibrating Payments

In most currently planned public- and private-sector initiatives, the overriding priority is achieving budget neutrality for payers. For example, this is an explicit consideration in the multi-payer medical home pilot in Rhode Island. Payers base payment levels on estimates of the savings they might achieve—for example, from reduced use of emergency department services and redundant testing. Payers would expect these savings to be offset by increases in other spending categories, such as preventive care. At the extreme, one private initiative has cautiously adopted a “pay-as-you-go” approach, by promising to share actual savings with physicians.

Payers are not yet at the point where they are willing to add payment for currently nonreimbursed services without a reasonable chance that it will be offset by savings elsewhere. Yet, in the setting of pilots and demonstrations, payers are much better positioned than physicians to take risks and absorb potential losses from the experiment. They could do so by reducing their focus on budget neutrality and relying more heavily on cost estimates of services and/or the level of incentive that will entice physicians to participate.

The Medicare medical home demonstration will actually attempt to price medical home services and reimburse physicians based on costs, as estimated by the Relative Value Update Committee (RUC). In contrast, few private-sector initiatives are taking this bottom-up approach, which physicians may perceive as more scientifically sound and fair but which requires much more painstaking data collection than private payers have been willing to wait or pay for. One notable exception is the Vermont medical home pilot, which reviewed related public and private programs and consulted with physician organizations, other stakeholders and payment experts to assess costs of typical “transformation of care processes,” such as hiring part-time nurses.

To anticipate how physicians might react to different payment levels, payers have to consider not only the costs of required medical-home capabilities, but also the average proportion of practice revenues that eligible patients represent for a typical physician. Most medical home initiatives involve a single payer, with payments that would, therefore, represent a minority, although possibly a substantial one, of a physician’s revenues. This is true even for the MMHD (Medicare accounts for roughly 30% of a primary care physician’s revenues) and initiatives in communities with highly concentrated private payer markets. The revenue sources for a given practice are important to consider because physicians will judge proposed payment levels based on whether they are high enough to amortize investment costs and cover operating costs of new medical-home capabilities. Most initiatives do not explicitly cover investment costs, and the size of a physician’s patient panel is largely fixed. Therefore, physicians’ interest in participating may depend on whether they believe that payments exceed their likely operating costs by a large enough margin to offset their investment costs. Multi-payer initiatives would cover a larger percentage of a physician’s patient panel, dangling the promise of greater revenue gains to entice physicians to invest in practice improvements.

With the many uncertainties in the cost and value of medical home services, there is a golden opportunity for payers and physician organizations to collect detailed information on how physician practices transform themselves to achieve medical-home capabilities and the associated costs of those changes. Such data could not only help inject scientific rigor into the correction of payment levels as programs evolve, but also could clarify the level of effort that patients with different disease burdens require of medical homes, help identify the medical-home capabilities that are most cost effective, and inform judgments about the long-term sustainability of the model.

Taking Reasonable Risks Ahead of Data

![]() rom a broader policy perspective, it is worth questioning whether the earnest

efforts to accurately price medical home services are a useful first step to

achieving lasting payment reform. If the risk to the primary care infrastructure

of doing nothing is as grave as consensus suggests, then payers may need to

take a comparable risk to address the problem. At the moment, payers have much

greater capacity to assume risk than do physicians—both in terms of resources

and their potential to influence the behavior of other providers. Moreover,

physicians are far less likely to invest in transforming their practices for

pilots of limited duration than for an ongoing program with sustained political

support.

rom a broader policy perspective, it is worth questioning whether the earnest

efforts to accurately price medical home services are a useful first step to

achieving lasting payment reform. If the risk to the primary care infrastructure

of doing nothing is as grave as consensus suggests, then payers may need to

take a comparable risk to address the problem. At the moment, payers have much

greater capacity to assume risk than do physicians—both in terms of resources

and their potential to influence the behavior of other providers. Moreover,

physicians are far less likely to invest in transforming their practices for

pilots of limited duration than for an ongoing program with sustained political

support.

Broad and lasting reform involves many technical and political steps pursued over many years. Demonstrations and pilots may merely be the first step in reform. Physicians are trained to order diagnostic tests only when they expect the results to affect future decision making, and not just to gather information for its own sake, because of the inconvenience and potential risk of complications to patients and the expense involved. Similarly, payers might consider whether their commitment to paying for medical home services or increasing their financial support for primary care in other ways will wane if they discover that medical home initiatives do not save money.

If payers are committed to increasing support for primary care regardless of the outcomes of medical home pilots, then they could design payments that at best achieve budget neutrality or even result in spending increases. That is, budget neutrality may be an admirable long-term goal, but an unrealistic expectation at every step of reform. Payers could implement such payments broadly—for all primary care physicians who achieve medical-home capabilities—rather than just in isolated initiatives. Then they could track physician performance and patient outcomes and adjust the program as needed over time. Precedents for this more aggressive approach include some of the most dramatic changes to Medicare payment policy—establishment of the Medicare inpatient prospective payment system and the resource-based relative value scale for physician services.

Medical Homes as a Stepping Stone to Broader Payment Reform

![]() n the long term, medical home payment approaches could serve as a model for

transitioning payment for care of chronic conditions from fee for service to

capitation as much as possible. Coupling capitation with bonuses based on system

cost savings and quality outcomes would better align incentives for preventive

care, coordination and quality improvement.57, 58

n the long term, medical home payment approaches could serve as a model for

transitioning payment for care of chronic conditions from fee for service to

capitation as much as possible. Coupling capitation with bonuses based on system

cost savings and quality outcomes would better align incentives for preventive

care, coordination and quality improvement.57, 58

The daunting constraints of already soaring health care spending imply that

long-term improvements in primary care payment might need to occur in a zero-sum

fashion involving shifts of resources from non-primary care services. Payers

can influence the degree to which this shift is gradual and acceptable to specialists.

Paying for medical home services without immediate expectations of budget neutrality