Market in Turmoil as Physician Organizations Stumble:

Orange County, California

Community Report No. 10

Spring 1999

Douglas L. Fountain, Joy M. Grossman, Roger S. Taylor, Effie Gournis, Claudia Williams

![]() n December 1998, a team of researchers visited Orange County, Calif.,

to study that community’s health system, how it is changing and the impact

of those changes on consumers. More than 40 leaders in the health care

market were interviewed as part of the Community Tracking Study by the

Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC) and The Lewin Group.

Orange County is one of 12 communities tracked by HSC every two years

through site visits and surveys. Individual community reports are

published for each round of site visits. The first site visit to

Orange County, in January 1997, provided baseline information against

which changes are being tracked. The Orange County market includes

approximately 30 cities that are immediately south of Los Angeles County.

n December 1998, a team of researchers visited Orange County, Calif.,

to study that community’s health system, how it is changing and the impact

of those changes on consumers. More than 40 leaders in the health care

market were interviewed as part of the Community Tracking Study by the

Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC) and The Lewin Group.

Orange County is one of 12 communities tracked by HSC every two years

through site visits and surveys. Individual community reports are

published for each round of site visits. The first site visit to

Orange County, in January 1997, provided baseline information against

which changes are being tracked. The Orange County market includes

approximately 30 cities that are immediately south of Los Angeles County.

![]() range County’s health care market has undergone dramatic upheaval over the past two years, as cost pressures mounted. Area health plans have long delegated risk and medical management to physicians, leading to the emergence of large physician organizations that play a critical role in the delivery system. In 1996, physician organizations, hospital systems and several plans were

implementing large-scale mergers to gain negotiating leverage and economies

of scale. Between 1996 and 1998, premiums were relatively flat, despite

increases in the cost of medical care. because of the high degree of

capitation, physician organizations bore the brunt of the cost increases.

range County’s health care market has undergone dramatic upheaval over the past two years, as cost pressures mounted. Area health plans have long delegated risk and medical management to physicians, leading to the emergence of large physician organizations that play a critical role in the delivery system. In 1996, physician organizations, hospital systems and several plans were

implementing large-scale mergers to gain negotiating leverage and economies

of scale. Between 1996 and 1998, premiums were relatively flat, despite

increases in the cost of medical care. because of the high degree of

capitation, physician organizations bore the brunt of the cost increases.

Key changes since 1996 include:

- Two national physician practice management

companies (PPMCs) filed for bankruptcy, and other physician organizations

posted losses or downsized.

- Although Kaiser Permanente gained market share, it experienced its first financial loss in its 50-year history in 1997.

- Hospitals continued the slow process of consolidation, gaining some

market leverage.

- Medicaid managed care implementation proceeded smoothly, but safety net providers continue to struggle.

- Market Defined by Managed Care and Consolidation

- Physician Organizations Squeezed by Cost Increases

- Physician Integration Is Costly and Slow

- Physician Organizations Falter

- Soaring Enrollment Leads to Financial Losses for Kaiser

- Hospitals Benefit from Consolidation

- Medicaid Managed Care Proceeds Smoothly, but Safety Net Strained

- Issues to Track

- Orange County Compared to Other Communities HSC Tracks

- Background and Observations

Market Defined by Managed Care and Consolidation

![]() ituated between Los Angeles and

San Diego, the Orange County health care market is shaped, on the one hand, by

being a part of Southern California, where statewide purchasing pools and large

regional employers influence the strategies of health plans and providers. On

the other hand, the vast geographic scope of the region leaves Orange County a

distinct local market for health care, shaped by a strong local economy, a

politically conservative environment and a rapidly growing population marked

by ethnic diversity and economic disparity.

ituated between Los Angeles and

San Diego, the Orange County health care market is shaped, on the one hand, by

being a part of Southern California, where statewide purchasing pools and large

regional employers influence the strategies of health plans and providers. On

the other hand, the vast geographic scope of the region leaves Orange County a

distinct local market for health care, shaped by a strong local economy, a

politically conservative environment and a rapidly growing population marked

by ethnic diversity and economic disparity.

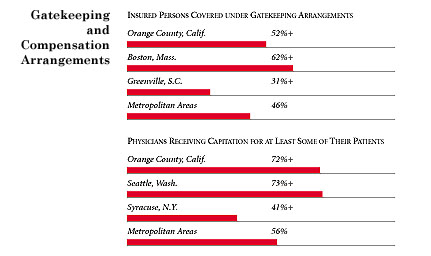

Orange County has extensive experience with managed care, and today it is one of the defining features of the health care system. In 1996, 46 percent of the county’s publicly and privately insured residents were enrolled in health maintenance organizations (HMOs), compared with 32 percent for all U.S. metropolitan areas, and the remainder were mostly in preferred provider organizations (PPOs).

Even more notable, however, is the prevalence of capitation in the market. Orange County’s health plans have delegated significant risk to physician organizations, typically paying capitation for primary and specialty care, as well as some ancillary services. Unlike many other markets, physician organizations in Orange County also typically share risk for hospital utilization and have responsibility for care management. While plans have broad networks, and most providers contract with most plans, capitation has resulted in tightly managed gatekeeping systems with clearly defined subnetworks controlled by physician organizations. As a result, consumers’ access to care is largely directed by their primary care physician and associated provider network.

By 1996, significant consolidation had taken place or was underway in all three sectors of the market:

- Four of the major health plans in

the county had consolidated, resulting in substantial concentration in the market.

For example, after acquiring FHP International, Inc., PacifiCare Health Systems

held two-thirds of

the county’s profitable Medicare

risk business.

- A series of mergers and acquisitions

in the Orange County hospital market concentrated more than half of the hospital

beds in three major systems. As a result of its national merger

with OrNda, Tenet Healthcare Corp.’s

11 local hospitals alone control more than 29 percent of the market’s beds.

- In the physician sector, consolidation was also underway, with the formation and growth of several large physician intermediary organizations led by PPMCs and local hospitals.

Since 1996, all three sectors have shifted from planning the mergers to consolidating and leveraging the merged entities. Physician organizations pursued these objectives while continuing to expand as well.

Physician Organizations Squeezed by Cost Increases

![]() hile Orange County’s health care

organizations grappled with how to

consolidate, industry costs began to

rise. Between 1996 and 1998, however,

premiums remained relatively flat-or grew by only a few percentage

points-largely due to competitive pricing in the region. Physician

capitation rates, likewise, remained steady, and rising costs hit

physician organizations particularly hard.

hile Orange County’s health care

organizations grappled with how to

consolidate, industry costs began to

rise. Between 1996 and 1998, however,

premiums remained relatively flat-or grew by only a few percentage

points-largely due to competitive pricing in the region. Physician

capitation rates, likewise, remained steady, and rising costs hit

physician organizations particularly hard.

In contrast to other markets where plans bear the brunt of these types of cost increases, the extensive use of capitation in Orange County meant that, in this market, physician organizations were financially at risk for delivering care under prepaid arrangements. Because physicians were often locked into long-term capitated contracts that did not account for rising costs, they had to tap into reserves or owner investments to fulfill this obligation.

Between 1996 and 1998, as in preceding years, physician organizations sought to expand the scope of their capitated services to increase their potential margin, driven partly by the belief that capitation rates for basic physician services were fairly bare-bones. Physicians continued to seek hospital risk-sharing arrangements, reasoning that good management of ambulatory care would result in lower hospital utilization and greater savings.

In addition, some of the more advanced physician organizations pursued capitation for pharmacy costs; others took it on, though reluctantly. Some physician organizations also sought global capitation - a consolidated payment to cover all medical services, including both physician and hospital-provided care.

As physician capitation arrangements expanded in scope, local health care costs grew beyond expectations because of a variety of factors:

Policy Changes. Several federal and state policy changes made over the past two years led to cost increases that physicians needed to absorb under capitation. For example, new legislation established a variety of mandated benefits guaranteeing coverage of certain services, which, according to physician organizations, led to considerable cost increases. Costs also rose with new requirements for physician-level encounter data for Medicare risk products and purchasers’ quality and patient satisfaction measures.

Changes in Health Plan Offerings. In 1996, more loosely managed HMO products - such as point-of-service (POS) products that cover enrollees for out-of-network care - were gaining in popularity among consumers, who felt constrained by tightly managed physician networks. In an effort to be more consumer-friendly, many health plans also instituted new grievance procedures, which resulted in increased retrospective approval of services.

Providers reported that these arrangements drove up costs, while in some cases decreasing physicians’ capitated payment. For example, under POS products, plans typically reduced physician capitation to account for enrollees treated by out-of-network providers. However, enrollees reportedly would go out-of-network for referrals, then come back to in-network physicians for treatment. As a result, providers reported that in-network utilization was higher than expected under POS products, leaving physicians with insufficient payment to cover costs and diminished control over utilization.

New Drugs and Medical Technologies. In keeping with national trends, local expenditures on pharmaceuticals and new medical technologies have grown rapidly. Locally, where many new contracts delegated risk for pharmacy, physician organizations had to absorb these costs.

Physician Integration Is Costly and Slow

![]() hile costs rose and

revenues plateaued, physician organizations struggled to realize the

expected benefits of consolidation. Integration efforts proved

more difficult and time-consuming

than expected, however, and the costs

associated with consolidation exceeded the benefits achieved, at least in the

short term, for three major reasons.

hile costs rose and

revenues plateaued, physician organizations struggled to realize the

expected benefits of consolidation. Integration efforts proved

more difficult and time-consuming

than expected, however, and the costs

associated with consolidation exceeded the benefits achieved, at least in the

short term, for three major reasons.

- First, physician organizations paid high prices for the practices

they acquired. In competing for geographic depth and breadth, PPMCs

and other buyers bid up the price for physician practices.

- Second, the cost of integrating

practices, and the difficulty of melding the practice styles of

diverse physician organizations, was greater than anticipated.

For example, some respondents noted the difficulty of translating

care management techniques across diverse practice arrangements.

- Third, the organizations needed to renegotiate plan contracts, rationalize physician payment arrangements and establish common information systems. New and often costly and redundant layers of overhead were added to manage these larger, more complex organizations.

There were some gains for a few physician organizations, however. MedPartners, a PPMC, and St. Joseph’s Health System reportedly got better rates from plans for physician members than the physicians could have gotten on their own, and MedPartners had begun to consolidate physical space. But overall, physician organizations did not realize quick returns on their investments, nor did they achieve one of their major promises - the advancement and broad-scale dissemination of sophisticated clinical information systems.

Physician Organizations Falter

![]() s cost pressures outpaced

the benefits of integration, physician organizations faced significant financial

difficulty. The 600-member Monarch IPA reported a

15 percent drop in commercial revenue between 1997 and 1998. And in 1998, the

prominent Bristol Park Medical Group laid off staff and closed four clinics.

s cost pressures outpaced

the benefits of integration, physician organizations faced significant financial

difficulty. The 600-member Monarch IPA reported a

15 percent drop in commercial revenue between 1997 and 1998. And in 1998, the

prominent Bristol Park Medical Group laid off staff and closed four clinics.

The most significant disruption was the downfall of the two major PPMCs, motivated largely by Wall Street investors, who, disappointed by poor initial returns, pulled out their capital. The demise of these organizations had profound implications for the market. They had purchased the assets of numerous physician practices and IPAs in Orange County and established intermediaries that assumed risk; their dissolution disrupted key arrangements for the delivery and financing of care.

The San Diego-based PPMC, FPA Medical Management, Inc., had grown rapidly in response to pressure from Wall Street investors. It acquired 600 physician members in Orange County through its March 1998 purchase of a large local medical group and its affiliated IPA. Only weeks later, FPA was in trouble - it was saddled with debt from its various acquisitions, had disappointing earnings and reportedly suffered from accounting and management problems. The company filed for bankruptcy in July, and by the end of 1998, it had sold all of its California practices and relocated its headquarters to Miami.

At roughly the same time, MedPartners was faltering. It experienced a failed merger with another national PPMC, PhyCor, in January 1998, and its stock value subsequently collapsed. By November 1998, the company announced its decision to get out of the physician practice management business nationwide.

Shaken by its failure to foresee FPA’s financial problems, the state Department of Corporations (DOC) acted quickly upon discovery of financial irregularities in MedPartners’ California operations. DOC intervened in March 1999 to seize control of the assets of MedPartners’ risk-bearing subsidiary, MedPartners Network (MPN), to make sure that health plans’ payments to the intermediary were used to pay providers locally and not to help bail out the corporate parent in Birmingham, Ala. DOC put MPN under a state conservator, who filed for bankruptcy on its behalf.

The Fallout. These developments raised serious concerns in the market about who is accountable under capitated arrangements for care that is paid for, but not yet delivered or reimbursed. Plans are holding physician intermediaries responsible, and providers who are owed money under FPA and MedPartners’ global capitation arrangements - an estimated $60 million and $73 million, respectively - want plans to be held liable. The California Medical Association (CMA) has filed a petition with DOC to force plans to cover FPA debts to providers, but this issue remains unresolved.

The PPMC failures also disrupted physicians’ contracts, raising concerns about patients’ ability to maintain access to their regular providers. Health plans and purchasers moved rapidly to establish alternative arrangements with physicians to minimize the disruption and to protect consumers’ access to their usual physicians. For example, one purchaser in Orange County intervened to ensure that its health plan would continue contracting with a physician group that had left the MedPartners network.

The state, however, has expressed concern that actions to protect plan and consumer interests could hurt efforts of physician organizations to stay afloat. Blue Cross of California attempted to transfer enrollees from MedPartners network providers throughout California in March 1999, but DOC blocked this action, fearing it would only undermine further MedPartners’ precarious financial position.

MedPartners and DOC reached a tentative settlement in April under which MedPartners agreed to pay its debts in California and to continue funding its California clinics and IPAs until they are all sold. In return, the state will retreat from its aggressive oversight of MPN, allowing MedPartners to resume responsibility for day-to-day operations. Significantly, the deal extends DOC’s oversight of MPN to include MedPartners’ California clinics and IPAs, which strengthens the state’s ability to ensure that patients maintain access to MedPartners’ physicians, and that physicians and hospitals are paid.

Long-Term Implications. California’s increasingly vigorous oversight of health plans and risk-bearing entities is expected to continue. In response to the local PPMC debacles, new regulations have been proposed to increase scrutiny of provider organizations that assume risk; these proposals are expected to be considered in the state legislature this year. In addition, legislation has been proposed that would limit plans’ ability to delegate risk for pharmacy costs to physicians.

The 1998 election of the first Democratic governor in 16 years also has raised expectations for increased market regulation. In recent months, there has been renewed discussion of either establishing a new regulatory entity or transferring this function from DOC to the Department of Health Services (DHS) to better monitor issues related to managed care.

Meanwhile, health plans have increased their scrutiny of physician organizations and have expressed a greater willingness to initiate corrective action when signs of financial trouble develop. On the whole, however, plans appear reluctant to drop capitation, and instead have focused on ways to improve delegated risk contracting.

Ultimately, respondents expect that physicians will feel the greatest effect from the failure of these organizations. Not only do they face potential financial liability for these entities’ unpaid claims, but now they are confronted with the decision of whether to stay with the organization when it is sold, join another group or IPA or go solo. This decision is particularly difficult for physicians who have sold all the assets of their practices to the PPMC.

This turmoil contributes to a general sense of uneasiness among physicians in the market. Overall, physicians in Orange County are concerned about reported declines in income. Anecdotal reports indicate that some are retiring early, leaving the area or targeting lucrative niches in the nonmanaged care market. Several respondents suggested that physicians were more cautious now of physician intermediary organizations, for example, avoiding exclusive affiliations and refusing to share data with them and health plans. Moreover, physician organizations are re-evaluating their risk exposure, which could lead some to push for new contracts to reduce their risk for pharmacy costs and Medicare business.

Finally, respondents expressed concern about the implications of these developments for local care management efforts. Struggling with organizational growth and mounting cost pressures, physician organizations in Orange County found it more difficult than expected to focus on advancing and further disseminating techniques for managing clinical care delivery. As physician organizations evolve in this market, it remains to be seen whether they will have the incentives and capital to adequately invest in these activities.

Soaring Enrollment Leads to Financial Losses for Kaiser

![]() aiser Foundation Health Plan,

the local leader in market share, experienced its first loss, posting a drop of

$270 million in 1997 and $288 million in 1998 on its business nationally, driven

largely by problems in the California market. As a group-model HMO, Kaiser

cushioned its physicians from the cost increases that other plans had passed

on through contractual arrangements with independent physician organizations.

aiser Foundation Health Plan,

the local leader in market share, experienced its first loss, posting a drop of

$270 million in 1997 and $288 million in 1998 on its business nationally, driven

largely by problems in the California market. As a group-model HMO, Kaiser

cushioned its physicians from the cost increases that other plans had passed

on through contractual arrangements with independent physician organizations.

Perhaps of greater consequence, however, Kaiser also had continued its aggressive efforts to build market share by limiting premium increases. With premiums 5 to 20 percent lower than most other plans, Kaiser enrollment soared to almost 300,000 members in Orange County, an increase of nearly 30 percent since 1996.

This burgeoning enrollment severely strained the capacity of Kaiser’s physicians and its hospitals. Kaiser has an exclusive relationship with its owned physician group and hospitals and referral relationships with a few contracted providers. In Orange County, Kaiser owns one hospital and leases wards at two other hospitals, but each of these was filled to capacity, so Kaiser had to pay high daily rates to place patients at other facilities. Moreover, the physician group absorbed the increased enrollment at a time when it was improving enrollees’ access to primary care physicians, further straining provider capacity.

To reverse its financial losses, Kaiser abandoned its strategy of holding down premiums and sought double-digit increases for 1999. The state public employee purchasing pool, for example, agreed to an increase of almost 11 percent. The plan also increased its hospital capacity statewide to reduce referrals to outside providers, and it postponed opening two physician clinics in Orange County to reduce operating costs. Kaiser expects these steps to yield positive returns this year and remains committed to its tightly integrated, exclusive group model.

Hospitals Benefit from Consolidation

![]() gainst the backdrop of

market turbulence, hospitals gained strength. Like physicians and health

plans, Orange County hospitals had consolidated in

the previous years. Since 1996, they

have sought to integrate to achieve

operational efficiencies and to bolster their leverage in the market.

gainst the backdrop of

market turbulence, hospitals gained strength. Like physicians and health

plans, Orange County hospitals had consolidated in

the previous years. Since 1996, they

have sought to integrate to achieve

operational efficiencies and to bolster their leverage in the market.

St. Joseph’s Health System, for example, pursued physician integration through a strategy of purchasing the assets of physician practices and IPAs and pressing for increased exclusivity under these arrangements. This allowed St. Joseph’s to consolidate contracting so that it could enter into "single-signature contracts" with plans that encompass all the services provided by the hospital system and its affiliated physicians. By bringing together several large hospitals and numerous physicians under an arrangement with increased exclusivity, St. Joseph’s reportedly was able to gain better rates from multiple health plans.

Tenet took a different approach - contracting with physicians and providing financial support for administration, rather than seeking ownership of groups. For example, Tenet was negotiating a 10-year capitated contract with MedPartners, although MedPartners’ financial troubles ultimately resulted in a more modest preferred provider arrangement. Tenet also merged contracting functions across its 11 Orange County hospitals, a move that helped some of its hospitals obtain new plan contracts but did not bring the expected gains in payment rates. At the same time, individual Tenet hospitals sought their own arrangements with physicians, in keeping with the system’s more arms-length approach.

In spite of initial gains from administrative integration, Orange County hospital systems have pursued little clinical integration to date. St. Joseph’s has had discussions about developing a common electronic medical record across the system, but these efforts are still in the planning stage. Tenet, likewise, has done little to integrate clinical functions, although it has achieved significant economies of scale through integration of some back-office functions and purchasing.

As Wall Street exits the local physician practice management market, hospitals increasingly may be looked to as sources of capital. Hospitals are in a strong position to benefit from the instability in the physician market, particularly as PPMCs sell off practices at much lower prices than they had previously. St. Joseph’s, for example, reportedly bought FPA’s large physician group and affiliated IPA for a fraction of what FPA had paid just months earlier. Despite the added leverage that these physician organizations may bring, it is unclear whether hospitals will pursue this business aggressively, given its demonstrated risks.

Medicaid Managed Care Proceeds Smoothly, but Safety Net Strained

![]() range County initiated

major reform of its health insurance programs for low-income and uninsured

people several years ago, and by all accounts, implementation of these

efforts is proceeding smoothly. In 1993, Orange County created CalOPTIMA,

a semi-autonomous entity charged with developing and

overseeing a mandatory Medicaid

managed care program that relied on capitated contracting. CalOPTIMA became

operational in 1995 and enrolled all recipients eligible through their

receipt of cash assistance, as well as those eligible under programs for

the aged and disabled. CalOPTIMA has won praise

for expanding access to providers;

currently, 85 percent of the county’s physicians now see Medi-Cal enrollees.

range County initiated

major reform of its health insurance programs for low-income and uninsured

people several years ago, and by all accounts, implementation of these

efforts is proceeding smoothly. In 1993, Orange County created CalOPTIMA,

a semi-autonomous entity charged with developing and

overseeing a mandatory Medicaid

managed care program that relied on capitated contracting. CalOPTIMA became

operational in 1995 and enrolled all recipients eligible through their

receipt of cash assistance, as well as those eligible under programs for

the aged and disabled. CalOPTIMA has won praise

for expanding access to providers;

currently, 85 percent of the county’s physicians now see Medi-Cal enrollees.

Through new contracts executed in 1998, the program is increasing its attention to clinical care management and quality improvement. CalOPTIMA purchases services for its Medi-Cal members via capitated contracts with health plans or physician-hospital consortia (PHCs) created specially for the program. New contracts changed the payment split between hospitals and physicians in favor of physicians, and altered physician-hospital risk-sharing arrangements begun in 1995 to reduce hospitalizations and increase coordination between physicians and hospitals.

CalOPTIMA also is raising the minimum number of enrollees for PHCs and health plans from 2,500 to 5,000 in an effort to reduce administrative burden to the participating plans and the program overall. This is intended to allow for a greater focus on quality improvement and to help plans manage enrollment declines due to welfare reform and improvements in the local economy. CalOPTIMA’s enrollment of people eligible through cash assistance programs has declined 30 percent since 1995.

Safety Net Providers. From its inception, CalOPTIMA took steps to ensure the participation of traditional safety net providers, but began contracting with plans and PHCs that included other hospitals and physicians as well. There is no public hospital in the county, and two hospitals - the University of California at Irvine Medical Center (UCIMC) and Children’s Hospital of Orange County (CHOC) - serve as the county’s major safety net hospitals. CalOPTIMA has attempted to support these and other safety net providers by favoring PHCs that include them in the assignment of members who do not select a plan voluntarily.

While UCIMC’s PHC has shown signs of enrollment growth recently, both safety net hospitals are now under significant financial pressure because many Medi-Cal beneficiaries enroll in other plans and PHCs that have broader geographic networks. UCIMC is seeking to increase its commercial patients to offset its declining Medi-Cal patient base, although commercial payments are also under pressure. CHOC received an influx of Medicaid disproportionate share funds between 1996 and 1998; however, the loss of the Medi-Cal volume puts those funds at risk at both hospitals.

Complicating matters for CHOC, local hospitals began charging lower prices for advanced pediatric care. As a result, commercial plans were lured away from CHOC, and the hospital’s occupancy rate dropped to 30 percent. It subsequently reduced staffing considerably, consolidated admissions and some administrative functions with neighboring St. Joseph’s and closed a clinic. Meanwhile, UCIMC also has cut back staffing, even though emergency room visits by indigent persons have increased and UCIMC-affiliated specialists at three community clinics are reportedly experiencing great increases in demand. UCIMC is one of few places in the county that provides free follow-up care with specialists for the indigent population.

Care for the Medically Indigent. Responsibility for care for the medically indigent remains the subject of much debate in Orange County. From the beginning, CalOPTIMA was slated to take over the county’s program for the medically indigent, Medical Services for the Indigent (MSI). Under California law, counties are responsible for providing care to the medically indigent; they use a mix of state revenues and their own funds to support this care. Despite recent small increases to specialists, annual funding is fixed, and the program reportedly reimburses providers for less than one-fifth of the cost of providers’ billed charges. While MSI has contributed to the cost of care for 20,000 indigent patients with medical need, this constitutes only a fraction of the estimated 335,000 uninsured adults in the county.

CalOPTIMA has been hesitant to take over MSI, wary of the overall financial implications of this responsibility and the lack of information about the size of this population and its health needs. CalOPTIMA and the county are now working on a pilot managed care program to develop data on costs and clinical care requirements as a way to consider these issues more carefully. The county also recently stepped up eligibility verification standards to better ensure that the program focuses on its intended population - a move that is expected to limit MSI enrollment.

Advocates for the poor remain concerned about the ability of the safety net to provide care to Orange County’s uninsured immigrant population, which continues to grow, particularly among Hispanics and Southeast Asians. Initiatives are underway to better serve this population, including a new community health center (CHC) serving Vietnamese immigrants and additional federal and grant funding for local CHCs.

However, many people in the county who need health care remain outside the mainstream of services, including immigrants, who may fear that using the public system could result in their deportation. This fear, as well as other cultural and socioeconomic barriers to care, has fueled reliance on so-called back office clinics where unlicensed individuals provide health care and distribute pharmaceuticals illegally. Recently, two children who were treated in unlicensed clinics died. County officials are exploring how to adapt the existing safety net to better serve the diverse populations in need of health care services.

Issues to Track

![]() any of the features of this

mature managed care market appear to be

fraying under financial pressures and consumer demands for more loosely managed

insurance products. Integration efforts have been slow and costly for hospitals

and physicians, and the high-profile failure of several large physician

organizations and difficulties of others present serious challenges to a

delivery system built on capitation and tight networks. Regulatory bodies

are stepping

up their scrutiny of risk relationships, and state policy changes appear

likely.

any of the features of this

mature managed care market appear to be

fraying under financial pressures and consumer demands for more loosely managed

insurance products. Integration efforts have been slow and costly for hospitals

and physicians, and the high-profile failure of several large physician

organizations and difficulties of others present serious challenges to a

delivery system built on capitation and tight networks. Regulatory bodies

are stepping

up their scrutiny of risk relationships, and state policy changes appear

likely.

The cost pressures that physicians have faced over the past two years remain and may intensify in the next few years. Additional benefit mandates and managed care regulations are expected from the state legislature, and decreasing Medicare payments under the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 will further constrain revenue for plans and providers.

However, health plans are raising premiums now and appear to be getting higher-than-historical increases in the short term. It remains to be seen whether premium increases will result in large enough payments to physician organizations to offset the severe financial pressures that confronted them over the past few years. In this environment, several other issues bear watching:

- How will physician organizations emerge from this turmoil? Where

will physicians displaced by the exit of MedPartners go? Will hospitals

begin to play a larger role in financing and leading physician

organizations, and, if so, will this lead to greater exclusivity?

- How will delegation of financial risk and care management evolve

in this market? What impact will these changes have on the development

and dissemination of clinical information systems and techniques to

improve clinical care?

- How will policy makers reshape the

way they monitor entities that assume financial risk for health care

delivery?

- How will employers react to premium increases, and what impact will

this have on consumers? Will the business community begin to lobby

against managed care regulation or seek other ways to control health

care costs?

- Will the county and CalOPTIMA find a mutually acceptable model for managed care for the uninsured? How will safety net providers fare in light of continued pressures from competition for Medicaid patients?

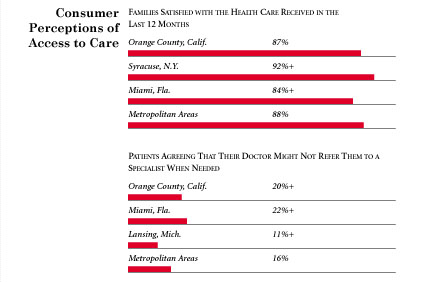

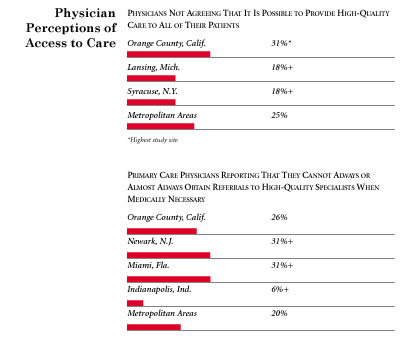

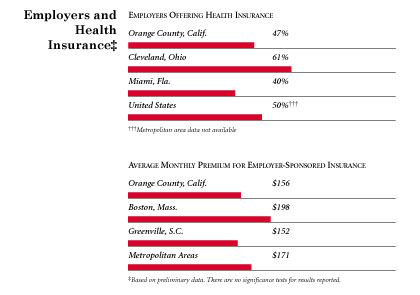

Orange County Compared to Other Communities HSC Tracks

Orange County, the highest and lowest HSC study sites and metropolitan areas with over 200,000 population

+ Site value is significantly different from the mean for metropolitan

areas over 200,000 population.

The information in these graphs comes from the Household, Physician and Employer

Surveys conducted in 1996 and 1997 as part of HSC’s Community Tracking Study. The

margins of error depend on the community and survey question and include +/- 2

percent to +/- 5 percent for the Household Survey, +/-3 percent to +/-9 percent

for the Physician Survey and +/-4 percent to +/-8 percent for the Employer Survey.

Background and Observations

Orange County Demographics

| Orange County, Cali. | Metropolitan areas above 200,000 population |

| Population, 19971 | |

| 2,674,091 | |

| Population Change, 1990-19971 | |

| 11% | 6.7% |

| Median Income2 | |

| $29,703 | $26,646 |

| Persons Living in Poverty2 | |

| 15% | 15% |

| Persons Age 65 or Older2 | |

| 10% | 12% |

| Persons with No Health Insurance2 | |

| 16% | 14% |

|

Sources: 1. U.S. Census, 1997 2. Household Survey Community Tracking Study, 1996-1997 | |

The Community Tracking Study, the major effort of HSC, tracks changes in the health system in 60 sites that are representative of the nation. Every two years, HSC conducts surveys in all 60 communities and site visits in the following 12 communities:

- Boston, Mass.

- Cleveland, Ohio

- Greenville, S.C.

- Indianapolis, Ind.

- Lansing, Mich.

- Little Rock, Ark.

- Miami, Fla.

- Newark, N.J.

- Orange County, Calif.

- Phoenix, Ariz.

- Seattle, Wash.

- Syracuse, N.Y.