Cleveland Hospital Systems Expand Despite Weak Economy

Community Report No. 2

September 2010

Aaron Katz, Amelia M. Bond, Emily Carrier, Elizabeth Docteur, Caroleen W. Quach, Tracy Yee

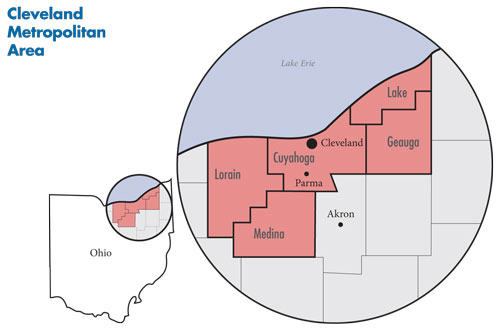

In March 2010, a team of researchers from the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC), as part of the Community Tracking Study, visited the Cleveland metropolitan area to study how health care is organized, financed and delivered in that community. Researchers interviewed more than 45 health care leaders, including representatives of major hospital systems, physician groups, insurers, employers, benefits consultants, community health centers, state and local health agencies and others. The study area encompasses Cuyahoga, Geauga, Lake, Lorain and Medina counties.

![]() he initiatives and strategies of Cleveland’s two largest health systems—Cleveland Clinic and University Hospitals (UH)—and the persistent fallout from the weak economy continue to shape the community’s health care market. Attracting well-insured suburban patients, expanding profitable specialty-service lines and winning physician loyalty are the main fields of competition between the two dominant health systems, leading to ever-more consolidation of the hospital and physician sectors. Though practitioners and hospitals unaffiliated with any organized health system remain, their independence is tenuous, according to market observers.

he initiatives and strategies of Cleveland’s two largest health systems—Cleveland Clinic and University Hospitals (UH)—and the persistent fallout from the weak economy continue to shape the community’s health care market. Attracting well-insured suburban patients, expanding profitable specialty-service lines and winning physician loyalty are the main fields of competition between the two dominant health systems, leading to ever-more consolidation of the hospital and physician sectors. Though practitioners and hospitals unaffiliated with any organized health system remain, their independence is tenuous, according to market observers.

The recession—and resulting high unemployment—and rising health care costs continue to strain consumers, employers and health care providers, who are shouldering more uncompensated care costs. Still, many viewed health care as one of the region’s strongest economic sectors, and the community hopes that growth in medical care and research can contribute to an economic turnaround. Others, however, questioned whether the continued competition between Cleveland Clinic and UH will lead to higher health care costs from excess capacity if the hospital systems can’t attract more patients from outside the Cleveland metropolitan area.

- Ongoing capacity expansions as Cleveland Clinic and University Hospitals compete for well-insured patients and physician loyalty, particularly in suburban areas, even as the local economy falters and the population declines.

- The continued shifting of health care costs from employers to employees, including greater use of high-deductible health insurance plans.

- A safety net system protected in the short run by federal stimulus funds but threatened in the longer run by ongoing state budget woes and the weak local economy.

- Economic Woes Continue Amid Population Decline

- Big Systems Get Bigger

- Hospitals Struggle to Maintain Independence

- Hospitals Woo Independent Physicians

- Health Plans Compete on Price and Customer Service

- Employers Continue Shifting Costs to Workers

- MetroHealth Anchors the Safety Net

- Community Works to Improve Access

- Public Sector Threatened by Budget Woes

- Anticipating Health Reform

- Issues to Track

- Background Data

Economic Woes Continue Amid Population Decline

![]() he population of the greater Cleveland metropolitan area (see map below) is now approximately 2.1 million, after declining almost 2 percent since 2004. The local economy has faced significant challenges from the prolonged economic downturn, including factory closures and the subsequent loss of good-paying jobs with generous health coverage. As younger residents have left to seek work elsewhere, a growing proportion of the Cleveland area’s population is 65 and older. The Cleveland area never fully recovered from the 2001 recession, with unemployment figures consistently and significantly above the national average. Market observers did not see any end to the region’s economic and employment woes.

he population of the greater Cleveland metropolitan area (see map below) is now approximately 2.1 million, after declining almost 2 percent since 2004. The local economy has faced significant challenges from the prolonged economic downturn, including factory closures and the subsequent loss of good-paying jobs with generous health coverage. As younger residents have left to seek work elsewhere, a growing proportion of the Cleveland area’s population is 65 and older. The Cleveland area never fully recovered from the 2001 recession, with unemployment figures consistently and significantly above the national average. Market observers did not see any end to the region’s economic and employment woes.

Even as the two dominant health systems continued to expand capacity, providers faced growing demand for uncompensated care as people lost their jobs and health insurance. The safety net for lower-income residents is anchored by the MetroHealth System, which is owned by Cuyahoga County, and several strong community-based clinics. Insurers in the market include Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Ohio, a subsidiary of the nation’s largest health insurer WellPoint; Medical Mutual, which previously held the Blue Cross Blue Shield trademark; Kaiser Foundation Health Plan; and such national plans as UnitedHealth Group, Aetna and CIGNA.

Big Systems Get Bigger

![]() he Cleveland Clinic and University Hospitals dominate the Cleveland health care market, and both systems were pursuing strategies to bolster market share, following what one observer called a “grow or die” ethos. But, market observers described the competition between the two as less intense and all-encompassing than in earlier periods. “There has not been as much nastiness,” according to one observer.

he Cleveland Clinic and University Hospitals dominate the Cleveland health care market, and both systems were pursuing strategies to bolster market share, following what one observer called a “grow or die” ethos. But, market observers described the competition between the two as less intense and all-encompassing than in earlier periods. “There has not been as much nastiness,” according to one observer.

Along with its large downtown campus, Cleveland Clinic has nine other hospitals in northeast Ohio, seven in Cuyahoga County, one south of Cleveland in Medina County and one in Ashtabula County, which borders Pennsylvania and is outside the study area; and more than 50 outpatient facilities throughout northeast Ohio. Consistent with its national and international reputation, Cleveland Clinic also has sites in Florida, Las Vegas, Toronto, and a new clinic and hospital scheduled to open in 2012 in Abu Dhabi.

University Hospitals includes UH Case Medical Center in downtown Cleveland, also the site of UH Ireland Cancer Center, Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital and MacDonald Women’s Hospital; two community hospitals in Cuyahoga County, one hospital in Geauga County east of Cleveland, and two hospitals in Ashtabula County outside the study area; affiliations with two community hospitals in Cleveland’s western and southwestern suburbs; and nearly 20 outpatient centers throughout northeast Ohio.

The Cleveland Clinic reportedly is the region’s largest employer with more than 30,000 workers, and University Hospitals is the second largest private employer with about 17,000 employees, including affiliated physicians. Both systems avoided significant layoffs during the 2007 recession, although Cleveland Clinic did institute a hiring freeze in late 2008. Cleveland Clinic and UH both reportedly have maintained strong financial performances but face challenges, including rising uncompensated care costs and declining or flat patient volume, according to respondents.

As has been the case for several years, Cleveland Clinic and University Hospitals have expanded capacity at their downtown campuses and increased their suburban presence by acquiring community hospitals, ambulatory centers and physician practices. Along with adding capacity at its downtown campus, Cleveland Clinic acquired Medina Hospital and added inpatient beds and renovated the emergency department at Hillcrest Hospital east of Cleveland. The system also reportedly plans to expand capacity at hospitals in Lakewood and Euclid.

University Hospitals will soon open Ahuja Medical Center in suburban Beachwood on Cleveland’s east side. The new hospital initially will have 144 beds but is designed for the addition of two towers for a total of 600 beds. UH also has added outpatient centers in Twinsburg, southeast of Cleveland, and in Concord Township in Lake County. Even while bolstering its suburban presence, UH continued to emphasize strong—and lucrative—specialty-service lines, largely at its downtown campus, where a new cancer hospital is scheduled to open in 2011. UH’s children’s hospital is the area’s recognized leader in pediatric inpatient and specialty care.

Commenting on the continued growth of Cleveland’s health care capacity, one observer noted, “There are many in Cleveland who believe that health care is a real economic driver for the community. It’s only an economic driver for the community to the extent that it’s exportable or that patients are imported. We should evaluate how that proposition works for Cleveland.”

To improve financial performance, both Cleveland Clinic and UH leaders envision transferring patients freely within their organizations, allowing them to match patients’ medical needs—and expected reimbursement—to the expertise and unit costs of individual admitting facilities. The goal is to manage complex, high-margin cases at the flagship academic hospitals with the highest unit costs per bed, while patients with less-complex needs are admitted to community hospitals. Both systems also were concentrating service lines at one or two high-volume sites to limit duplication. In addition, both Cleveland Clinic and University Hospitals were working to become more and more tightly integrated, both organizationally and clinically, using electronic medical records, quality initiatives and direct employment of physicians to exert greater control over the flow and costs of patient care.

Hospitals Struggle to Maintain Independence

![]() everal independent hospitals and smaller systems complete the Cleveland market, including Parma Community Hospital, the only remaining independent hospital in Cuyahoga County. Lake Health operates two hospitals and several outpatient centers in Lake County northeast of Cleveland, and Elyria Regional Health Care System operates in Lorain County west of Cleveland. To the south of Cleveland, Akron-based Summa Health System increasingly competes with the two big Cleveland systems as all three expand into suburban areas between Cleveland and Akron. For the most part, however, independent hospitals compete with each other but are generally ignored by the large systems unless they become targets for acquisition, according to market observers.

everal independent hospitals and smaller systems complete the Cleveland market, including Parma Community Hospital, the only remaining independent hospital in Cuyahoga County. Lake Health operates two hospitals and several outpatient centers in Lake County northeast of Cleveland, and Elyria Regional Health Care System operates in Lorain County west of Cleveland. To the south of Cleveland, Akron-based Summa Health System increasingly competes with the two big Cleveland systems as all three expand into suburban areas between Cleveland and Akron. For the most part, however, independent hospitals compete with each other but are generally ignored by the large systems unless they become targets for acquisition, according to market observers.

As the smaller, independent hospitals struggle to remain viable, market observers noted that the two large Cleveland-based systems continue to make inroads. “Across the board, UH gained a little and [the Cleveland Clinic] gained a little, and the remaining independent community hospitals have lost [ground],” one observer said.

For example, Parma was struggling to maintain its current business model as an independent hospital. With a payer mix heavily weighted toward Medicare and medical rather than surgical admissions, Parma officials were concerned about Medicare payment reductions included in federal health reform legislation. Similar to the larger systems, Parma was seeking closer affiliations with physicians, hoping tighter alignment will encourage physicians to perform more procedures on its campus, rather than at freestanding outpatient centers or competing hospitals. Parma also was focusing on core services, such as orthopedics and rehabilitation, and contracting with the larger systems for specialty coverage it can no longer sustain, including neurosurgery and oncology. Faced with an uncertain financial future, Parma had put all construction plans on hold.

Hospitals Woo Independent Physicians

![]() irroring the hospital market, physicians have been leaving small practices for larger ones and giving up independence in exchange for alignment with the larger health systems. Indeed, physician organizations affiliated with—by contract or employment—either Cleveland Clinic or University Hospitals dominate the physician community. The increased consolidation reportedly was a response to pressures from a weak economy and new requirements for health information technology and external quality reporting. Observers also noted that both younger physicians and those nearing retirement are choosing the stability of employment over the struggles of independent practice. Most physicians have an affiliation with only one of the larger systems, although they may work with a smaller independent hospital as well.

irroring the hospital market, physicians have been leaving small practices for larger ones and giving up independence in exchange for alignment with the larger health systems. Indeed, physician organizations affiliated with—by contract or employment—either Cleveland Clinic or University Hospitals dominate the physician community. The increased consolidation reportedly was a response to pressures from a weak economy and new requirements for health information technology and external quality reporting. Observers also noted that both younger physicians and those nearing retirement are choosing the stability of employment over the struggles of independent practice. Most physicians have an affiliation with only one of the larger systems, although they may work with a smaller independent hospital as well.

Creating stronger, loyal relationships with physicians was an explicit strategy of most of Cleveland’s hospitals. For example, the Cleveland Clinic Community Physician Partnership (CCCPP) offers a range of services, including practice management, legal services and relationships with vendors, to employed and affiliated health care providers—including physicians, psychologists and other practitioners. The partnership negotiates with payers for employed physicians as well as facilitating contracting for independent physician members, though not as a legal agent.

University Hospitals’ physician group offers a similar range of services to employed and affiliated physicians. Other hospitals were approaching anxious independent physicians by offering them paid part-time administrative and teaching roles that can supplement their independent practices, as well as paying for on-call emergency coverage. One respondent described the approach as “having a menu of opportunities available to physicians depending on their preferred alignment or employment model.”

Most hospitals were seeking to hire physicians, particularly primary care physicians, because they can offer a steady referral stream to employed specialty physicians who provide high-margin services. Hospitals also were expecting more demand for primary care services once health care reform’s coverage expansions take effect. Certain specialty services, such as neurosurgery, were in heavy demand as well. According to some reports, any qualified physician seeking employment in the Cleveland market could expect to receive offers from the Cleveland Clinic, UH, Summa and MetroHealth.

While some viewed unaffiliated medical practices as an unsustainable model, the trend toward consolidation was neither universal nor necessarily popular. In more rural parts of the Cleveland area, solo- and two-physician primary care and specialty practices still appeared to be prevalent, and in many communities, physicians maintain admitting privileges at more than one hospital—generally a large system and a smaller independent facility. In Cleveland itself, some independent physician respondents indicated many of their remaining peers view the push toward alignment with the larger systems with resignation, if not resistance.

Health Plans Compete on Price and Customer Service

![]() ost observers characterized Cleveland’s health insurance market as competitive, with both local and national players of various sizes vying for a larger piece of a shrinking pie. Medical Mutual is the largest insurer in the market followed by Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield. Kaiser Foundation Health Plan has the largest commercial health maintenance organization (HMO) enrollment, and national plans, including Aetna, UnitedHealth Group and CIGNA also have a presence in the market.

ost observers characterized Cleveland’s health insurance market as competitive, with both local and national players of various sizes vying for a larger piece of a shrinking pie. Medical Mutual is the largest insurer in the market followed by Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield. Kaiser Foundation Health Plan has the largest commercial health maintenance organization (HMO) enrollment, and national plans, including Aetna, UnitedHealth Group and CIGNA also have a presence in the market.

By far the most popular product in the market is the preferred provider organization (PPO). Insurers offer additional features that can be customized to an employer’s specifications, such as wellness programs—for example, smoking cessation, weight reduction or gym memberships.

Given the consolidated provider market, insurers have had difficulty differentiating themselves through innovative provider contracting or payment methods. Plans mostly pay providers using traditional methods—diagnostic-related groups, or DRGs, for hospitals and some percentage of Medicare’s fee schedule for physicians. Innovative payment arrangements, such as pay for performance or bundled payments—a single payment for all providers involved in an episode of care—have found little foothold in Cleveland. Likewise, health insurance products with narrow networks—a subset of the plan’s provider network—or tiered networks—a subset of the network’s providers designated as high-performing based on quality and/or cost measures and typically lower patient cost sharing—usually are not offered by Cleveland-area health plans. An exception is cases where the employer is a health care provider or system seeking to steer utilization to its own facilities and practitioners.

One notable factor in the insurance market is the longstanding relationship between the Cleveland Clinic and Medical Mutual, which excludes the downtown UH hospitals from Mutual’s provider network. The relationship is unusual for a market where patients reportedly place a high value on a wide choice of providers. Medical Mutual does not exclude UH entirely; its community hospitals typically are included in Mutual’s network, and the new UH facility on Cleveland’s east side may be included as well, perhaps a sign that the relationship is evolving.

Cleveland’s health plans, in general, appeared reluctant to attempt to influence provider behavior. Although plans reported undertaking some care coordination efforts and utilization management activities, including newly reinstated requirements to preauthorize imaging and other fast-growing services, such cost-control strategies do not appear to be a central focus or an important competitive strategy.

In a market with relatively little product and network differentiation, plans compete for customers primarily on the basis of price and customer service. As one health plan respondent said, “We’re trying to differentiate ourselves from everyone else, even though employers will look at price first, then price second, then price again. But with all things being close to equal, service is the differentiator.”

In the case of the small group market, price competition is complicated by the role of brokers, who act as intermediaries between small employers and insurers. Some respondents raised questions about potential conflicts of interest that arise when insurers reward brokers for steering clients to their products even when the product may not be the best fit for the customer, although one respondent commented that transparency has increased in recent years and reduced the extent of such conflicts.

Medical Mutual capitalizes on its local origins in competing for customers and was reportedly strongest in the small group market and with local employers. Medical Mutual’s products are the only ones offered by Cleveland’s Council of Smaller Enterprises, a small-business support organization that offers group purchasing of health benefits to its more than 15,000 members. The insurer’s competitive strategies notably focus on strong provider relations, including real-time claims adjudication, which is offered as a tool to help collect patient deductibles, copayments and coinsurance at the point of service, especially for patients with high-deductible plans.

Employers Continue Shifting Costs to Workers

![]() oth small and large employers in Cleveland reported ongoing pressure from rising health care costs, especially for hospital services, and the resulting increase in insurance premiums. Observers cited specific concerns about increases in emergency department visits, surgeries and diagnostic imaging. Insurers also noted that the highly consolidated provider market and resistance by both employers and providers to narrow- or tiered-network products limit their ability to exert downward pressure on hospital and physician prices.

oth small and large employers in Cleveland reported ongoing pressure from rising health care costs, especially for hospital services, and the resulting increase in insurance premiums. Observers cited specific concerns about increases in emergency department visits, surgeries and diagnostic imaging. Insurers also noted that the highly consolidated provider market and resistance by both employers and providers to narrow- or tiered-network products limit their ability to exert downward pressure on hospital and physician prices.

Cleveland-area insurers predominantly offer PPO products, typically with a $1,000 deductible for an individual, $3,000 deductible for a family and 20 percent coinsurance for in-network services. However, deductibles vary widely depending on firm size. The recent trend toward more use of high-deductible plans has apparently accelerated, and they are often provided in conjunction with a health savings account (HSA). The highest deductibles for small businesses average about $5,000 single/$10,000 family, but some employers have expressed interest in plans with $7,500/$10,000 deductibles. Most of these products offer first-dollar coverage of preventive health services, allowing employees to obtain some level of services before deductibles apply.

According to market observers, the small group market is the most sensitive to rising health care costs. These employers typically contribute a smaller share of the premium cost and offer less comprehensive benefits. Many expected employers to increase workers’ share of premium contributions.

Larger firms also were shifting costs to employees, primarily through higher deductibles and increasing the proportion of premiums paid by workers. Premium trends reportedly have increased about 10 percent a year. The trend toward higher patient cost sharing was evident even among public employers, with new contracts for state and municipal employees including deductibles in the four offered HMO products, while only the PPO option had a deductible previously. Out-of-pocket cost limits and copayments also were increased for all plans.

Despite the rise in high-deductible health plans, evidence of greater efforts around price and quality transparency for consumers was limited. One respondent observed that there is “a lot of talk, but nobody’s really doing anything.” Others, however, pointed to one regional initiative, Better Health Greater Cleveland (BHGC), that aims to provide quality information to physicians and consumers to achieve better clinical outcomes and increased efficiency. Funded in part by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Aligning Forces for Quality project, the initiative includes many of the area’s health care providers, payers, the city and county health departments, and community organizations. BHGC has issued performance reports for primary care providers, focusing on outcomes for patients with chronic conditions. The reports are to help practices improve quality using electronic medical records (EMRs), engage both providers and consumers in the quality-of-care arena, increase awareness of the data, and identify top performers. BHGC also was moving forward on projects targeting preventable hospital readmissions and helping providers using the same EMR system to exchange health information to improve care coordination.

MetroHealth Anchors the Safety Net

![]() etroHealth System continues to anchor Cleveland’s health care safety net after emerging from significant financial stress in the mid-2000s. Under new leadership, the system turned a reported $2.2 million loss in 2007 into a modest surplus the next year. To return to financial health, MetroHealth eliminated several hundred positions, worked to improve operational efficiency and began enforcing a $150 copayment for nonemergency care for uninsured patients living outside of Cuyahoga County. At the same time, MetroHealth expanded discounts for uninsured patients from a top limit of 200 percent of the federal poverty level, or $21,660 for a single person in 2010, to 400 percent of poverty to reduce the financial burden for uninsured patients.

etroHealth System continues to anchor Cleveland’s health care safety net after emerging from significant financial stress in the mid-2000s. Under new leadership, the system turned a reported $2.2 million loss in 2007 into a modest surplus the next year. To return to financial health, MetroHealth eliminated several hundred positions, worked to improve operational efficiency and began enforcing a $150 copayment for nonemergency care for uninsured patients living outside of Cuyahoga County. At the same time, MetroHealth expanded discounts for uninsured patients from a top limit of 200 percent of the federal poverty level, or $21,660 for a single person in 2010, to 400 percent of poverty to reduce the financial burden for uninsured patients.

MetroHealth operates an 860-bed hospital—MetroHealth Medical Center—in downtown Cleveland and nine community-based primary health care centers in Cuyahoga County. The medical center employs most of its physicians and links both community and hospital-based providers with an EMR. Although inpatient and outpatient capacity have not changed significantly in recent years, MetroHealth, which operates Cleveland’s sole Level I adult trauma center, recently issued $75 million in Build America Bonds to update its Metro Life Flight fleet—a critical care transport service—and to expand its outpatient primary care network.

With what observers described as new but tenuous stability, MetroHealth was viewed as neutral ground amid the Cleveland Clinic-University Hospitals rivalry. Neither large system has competed for MetroHealth’s core business of caring for Medicaid and uninsured patients. Indeed, MetroHealth is the only system in the Cleveland market to earn positive Medicaid margins and receive county funding to care for low-income, uninsured patients. Federal health care reform may present additional challenges for MetroHealth. A primary concern is loss of federal, state and local subsidies to support uncompensated care, especially as state and local governments grapple with budget shortfalls. Also, MetroHealth could face competition for Medicaid patients when Medicaid increases payment rates for primary care services in 2013 and expands coverage in 2014.

St. Vincent Charity Medical Center, owned by the Sisters of Charity Health System, serves as a secondary Cleveland safety net hospital, filling an especially important niche because the hospital has one of only two psychiatric emergency departments in the state. Like MetroHealth, St. Vincent has become more aggressive in enforcing sliding-scale-fee policies and collecting copayments.

Community Works to Improve Access

![]() leveland’s three main federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) are relatively strong, longstanding organizations that have weathered the recent economic recession. Northeast Ohio Neighborhood Health Services provides comprehensive adult and pediatric primary care services at six locations in Cuyahoga County. Neighborhood Family Practice also provides a wide range of primary care services at two sites, with a focus on the Hispanic community on the city’s west side. Care Alliance Health Center focuses on care for the homeless and public housing populations, providing services at three city locations.

leveland’s three main federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) are relatively strong, longstanding organizations that have weathered the recent economic recession. Northeast Ohio Neighborhood Health Services provides comprehensive adult and pediatric primary care services at six locations in Cuyahoga County. Neighborhood Family Practice also provides a wide range of primary care services at two sites, with a focus on the Hispanic community on the city’s west side. Care Alliance Health Center focuses on care for the homeless and public housing populations, providing services at three city locations.

Several federal grants have provided significant financial relief, and federal stimulus funding has allowed the health centers to expand capacity and renovate facilities, add staff, and move forward with health information technology initiatives. Unlike the FQHCs, The Free Medical Clinic of Greater Cleveland, which mostly serves adults, did not receive any federal stimulus funding but did obtain private funding to support some program enhancements.

Many observers cited dental care and behavioral health services, notably pediatric mental health care, as top access problems for low-income people in Cleveland—and Ohio more generally. One respondent called the mental health situation “a disaster…turned into a calamity” as the state Legislature cut community mental health funding by $171 million for fiscal years 2010 and 2011. Low-income people also have difficulty accessing specialty services for chronic care needs, such as podiatry, optometry and nutrition services for people with high-blood pressure and diabetes. Local initiatives to address these concerns include the following:

- Care Alliance has a strong dental care program that is in constant demand. To help create a funding stream to maintain an array of services, including dental care, the clinic staff took a 10-month “mini-MBA” training offered by Community Wealth Ventures and, subsequently, started a separate dental clinic for patients who were insured or could afford to pay cash.

- The Alcohol, Drug Addiction and Mental Health Services Board of Cuyahoga County was working to develop a central intake and referral system to better coordinate services for patients with behavioral health problems.

- The Free Medical Clinic has started a Saturday obesity and diabetes clinic with group educational sessions.

The most-frequently cited community-wide effort to improve access was the Cuyahoga Health Access Partnership (CHAP), which was created about two years ago to bring Cleveland’s major health care organizations together to better coordinate care for low-income residents. The partnership includes the Center for Community Solutions, Universal Health Care Action Network of Ohio, MetroHealth, Cleveland Clinic, University Hospitals, local public agencies and other safety net providers. Many observers expressed optimism that CHAP could improve efficiency, reduce emergency department use and expand capacity to serve low-income people. But some also characterized the initiative as moving “glacially slow” and indicated CHAP was too often a battlefield in the competition among the area’s major health systems.

Public Sector Threatened by Budget Woes

![]() hio’s Medicaid program has undergone important changes in recent years, but state budget problems have stalled some initiatives. The state completed enrollment of the Medicaid aged, blind and disabled population into managed care plans in early 2007, bringing the total proportion of Medicaid enrollees now in managed care to about 75 percent. Medicaid managed care plans reported that serving this more medically complex group of patients was a challenge and required improved care management and coordination capacities and expanded behavioral health capabilities.

hio’s Medicaid program has undergone important changes in recent years, but state budget problems have stalled some initiatives. The state completed enrollment of the Medicaid aged, blind and disabled population into managed care plans in early 2007, bringing the total proportion of Medicaid enrollees now in managed care to about 75 percent. Medicaid managed care plans reported that serving this more medically complex group of patients was a challenge and required improved care management and coordination capacities and expanded behavioral health capabilities.

In a move that may further complicate care for Medicaid patients, the state carved out prescription drug coverage for Medicaid managed care enrollees in February 2010, in part to obtain larger rebates from pharmaceutical companies and to reduce confusion over plans’ multiple formularies. Previously, managed care plans were responsible for providing all pharmacy benefits to Medicaid enrollees. Now, Medicaid managed care enrollees use the state’s fee-for-service pharmacy benefit for drugs dispensed in retail settings, and the state is responsible for pharmacy claims processing and prior-authorization activities. Drugs dispensed in physician offices or hospital outpatient clinics remain under managed care plan authority and payment. Though too early to assess, observers were concerned that Medicaid patients would now have to pay $2 to $3 copayments that the plans previously waived and that plans would have more difficulty managing patients’ care without direct responsibility for prescription drugs or related utilization data.

State budget pressures also have affected Medicaid payment rates. After an average 3-percent increase in provider payments in 2007-08, these increases were reversed in the 2010-11 fiscal years to help balance the state budget. What one observer described as “just another stop-gap measure” to balance the budget, the state instituted a new fee on hospitals in 2009 that has generated more than a billion dollars in tax revenue and federal Medicaid matching funds. Although some of these new revenues were used to increase hospital Medicaid payment rates by about 5 percent, many hospital executives lamented that the fee is a net cost to them.

State budget woes also derailed eligibility expansion for Ohio’s Healthy Start program for children and pregnant women from 200 percent to 300 percent of poverty, which the state Legislature approved as part of the 2008-09 budget. The expansion was to be funded by tobacco settlement dollars, but that money has been held up pending the outcome of a lawsuit.

The fate of local human services funding was put at risk by a corruption scandal involving public officials and contractors in Cuyahoga County. County officials and employees were accused of improperly awarding public contracts. The scandal raised fears that voters would not approve a May 2010 levy to fund county health and human services. The levy did pass, providing about $86 million a year in ongoing support to MetroHealth, the Alcohol, Drug Addiction and Mental Health Services Board and the Cuyahoga County Board of Health.

Anticipating Health Reform

![]() nactment of national health reform has been greeted by most players in Cleveland’s health system with cautious optimism. Most observers praised and looked forward to the law’s coverage expansions, which they expected to cut deeply into the area’s large uninsured population. However, health plans and employers were concerned that the new law will not curb the growth of underlying health care costs that drive health insurance premium trends. And provider organizations were worried that the influx of newly insured patients would worsen already strained primary care capacity.

nactment of national health reform has been greeted by most players in Cleveland’s health system with cautious optimism. Most observers praised and looked forward to the law’s coverage expansions, which they expected to cut deeply into the area’s large uninsured population. However, health plans and employers were concerned that the new law will not curb the growth of underlying health care costs that drive health insurance premium trends. And provider organizations were worried that the influx of newly insured patients would worsen already strained primary care capacity.

Safety net providers, along with Cleveland Clinic and University Hospitals, also were confident they would benefit from the new federal focus on health information technology and EMRs included in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009.

Issues to Track

- Will the ongoing capacity expansions by the Cleveland Clinic and University Hospitals be sustainable if the local economy does not improve and if health care reform efforts are successful in placing downward pressure on prices and emphasizing primary over specialty care?

- Will rising health costs in a time of economic downturn spur innovation in design of health plans to include narrow- or tiered-provider networks, or will the current trend of increasing patient cost sharing in plans with relatively broad provider networks continue?

- Will MetroHealth be able to maintain its hard-fought-for improved financial status in the face of the region’s poor economic outlook and possible cuts in Medicare and Medicaid payment rates?

- Will the Cuyahoga Health Access Partnership overcome turf issues and create a coordinated system

Background Data

| Cleveland Demographics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Cleveland Metropolitan Area | Metropolitan Areas 400,000+ Population | |

| Population, 20091 | 2,091,286 | |

| Population Growth, 5-Year, 2004-20092 | -1.8%* | 5.5% |

| Age3 | ||

| Under 18 | 23.5% | 24.8% |

| 18-64 | 61.9% | 63.3% |

| 65+ | 14.7% | 11.9% |

| Education3 | ||

| High School or Higher | 88.0% | 85.4% |

| Bachelor’s Degree or Higher | 27.0% | 31.0% |

| Race/Ethnicity4 | ||

| White | 73.2% | 59.9% |

| Black | 19.3% | 13.3% |

| Latino | 4.3% | 18.6% |

| Asian | 1.8% | 5.7% |

| Other Races or Multiple Races | 1.4% | 4.2% |

| Other3 | ||

| Limited/No English | 3.4% | 10.8% |

|

* Indicates a 12-site largest decrease. Sources: 1 U.S. Census Bureau, Annual Population Estimate, 2009 2 U.S. Census Bureau, Annual Population Estimate, 2004 and 2009 2 U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2008 3 U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2008, weighted by U.S. Census Bureau, Annual Population Estimate, 2008 |

||

| Economic Indicators | ||

|---|---|---|

| Cleveland Metropolitan Area | Metropolitan Areas 400,000+ Population | |

| Individual Income less than 200% of Federal Poverty Level1 | 29.6% | 26.3% |

| Household Income more than $50,0001 | 49.4% | 56.1% |

| Recipients of Income Assistance and/or Food Stamps1 | 10.9% | 7.7% |

| Persons Without Health Insurance1 | 11.0% | 14.9% |

| Unemployment Rate, 20082 | 6.8%* | 5.7% |

| Unemployment Rate, 20093 | 9.1% | 9.2% |

| Unemployment Rate, March 20104 | 9.8% | 10.4% |

* Indicates a 12-site high. Sources: |

||

| Health Status1 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Cleveland Metropolitan Area | Metropolitan Areas 400,000+ Population | |

| Chronic Conditions | ||

| Asthma | 15.4% | 13.4% |

| Diabetes | 8.6% | 8.2% |

| Angina or Coronary Heart Disease |

5.3% | 4.1% |

| Other | ||

| Overweight or Obese | 60.6% | 60.2% |

| Adult Smoker | 17.7% | 18.3% |

| Self-Reported Health Status Fair or Poor |

15.1% | 14.1% |

| Sources: 1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2008 |

||

| Health System Characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Cleveland Metropolitan Area | Metropolitan Areas 400,000+ Population | |

| Hospitals1 | ||

| Staffed Hospital Beds per 1,000 Population | 3.6 | 2.5 |

| Average Length of Hospital Stay (Days) | 5.5 | 5.3 |

| Health Professional Supply | ||

| Physicians per 100,000 Population2 | 286 | 233 |

| Primary Care Physicians per 100,000 Poplulation2 | 95 | 83 |

| Specialist Physicians per 100,000 Population2 | 191 | 150 |

| Dentists per 100,000 Population2 | 65 | 62 |

Average monthly per-capita reimbursement for beneficiaries enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare3 |

$711 | $713 |

Sources: 1 American Hospital Association, 2008 2 Area Resource File, 2008 (includes nonfederal, patient care physicians) 3 HSC analysis of 2008 county per capita Medicare fee-for-service expenditures, Part A and Part B aged and disabled, weighted by enrollment and demographic and risk factors. See www.cms.gov/MedicareAdvtgSpecRateStats/05_FFS_Data.asp. |

||