Syracuse Health Care Market Works to Right-Size Hospital Capacity

Community Report No. 9

August 2011

Ha T. Tu, Robert A. Berenson, Dori A. Cross, Ian Hill, Caroleen W. Quach, Divya R. Samuel

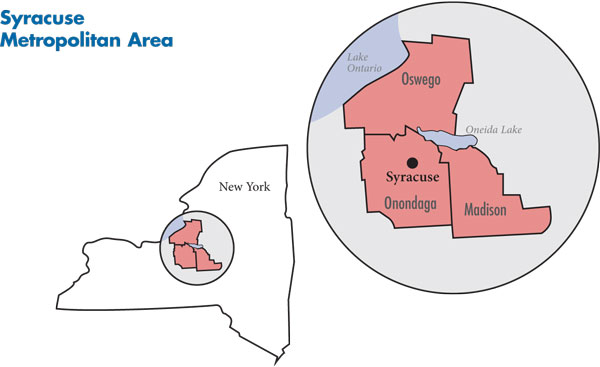

In October 2010, a team of researchers from the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC), as part of the Community Tracking Study (CTS), visited the Syracuse metropolitan area to study how health care is organized, financed and delivered in that community. Researchers interviewed more than 40 health care leaders, including representatives of major hospital systems, physician groups, insurers, employers, benefits consultants, community health centers, state and local health agencies, and others. The Syracuse metropolitan area encompasses Madison, Onondaga and Oswego counties.

Largely stable over the last three years, the Syracuse health care market continues to grapple with the challenge of finding the right level and mix of hospital capacity. The community has long had four general acute-care hospitals—one public academic medical center and three private, nonprofit hospitals—serving a relatively small population. Previous attempts to trim inpatient capacity through consolidation all ended in failure, with merging hospitals unable to resolve differences in physician cultures, business philosophies and management styles. However, the most recent proposed merger—public Upstate University Hospital’s acquisition of private Community General Hospital—did come to fruition in mid-2011, as most observers had expected. If this merger is successful, it will allow Upstate to relieve acute capacity constraints and Community to reverse the recent exodus of physicians and patients and remain a viable service facility.

Historically, Syracuse has lagged other communities in health-sector developments, and this continued to hold true in recent years. Trends seen in other markets—such as hospital employment of physicians, consolidation of physician groups and the growth of consumer-driven health care—have been taking place in Syracuse but at a slower pace and with less intensity than seen elsewhere.

Key developments include:

- The Upstate-Community merger was widely viewed as a net positive for the Syracuse community, although some payers were concerned that the consolidation may lead to increased hospital prices. How the merged entity will handle longstanding tensions between academic physicians and community physicians remains to be seen.

- Excellus Blue Cross Blue Shield increased its dominance in the small-to-mid-sized insurance market segments but lost some large, prominent self-insured accounts, as local employers questioned Excellus’ data-reporting capabilities and commitment to the Syracuse community.

- Despite severe budget woes, New York state not only expanded already generous eligibility standards for Medicaid and related public insurance programs, but also streamlined enrollment and renewal, leading to more Syracuse residents gaining public coverage.

- Long-Term Economic Decline, but Less Severe Recession

- Hospital Capacity Enigma: Too Many Beds or Not?

- Moderate Increases in Consolidation, Hospital Employment of Physicians

- Excellus Faces Challenges

- Moderate Cost Sharing Increase

- Relations Improve Between Excellus and Providers

- Most Safety Net Providers Faring Well Despite Challenges

- Expanded Medicaid Eligibility, Streamlined Enrollment

- Anticipating Health Reform

- Issues to Track

- Background Data and Funding Acknowledgement

Long-Term Economic Decline, but Less Severe Recession

![]() he Syracuse metropolitan area (see map below) has been in long-term economic decline, as the community lost its manufacturing base over the past several decades. As the economy declined, so did the Syracuse area’s population. In recent years, the population of the Syracuse metropolitan area has stabilized at approximately 650,000 people. On average, Syracuse residents are somewhat older and have slightly lower incomes and poorer health on some measures, such as heart disease, asthma and smoking status, than residents of other metropolitan areas. Compared with other metropolitan areas, Syracuse is less ethnically and racially diverse, with relatively small proportions of black, Latino and Asian residents.

he Syracuse metropolitan area (see map below) has been in long-term economic decline, as the community lost its manufacturing base over the past several decades. As the economy declined, so did the Syracuse area’s population. In recent years, the population of the Syracuse metropolitan area has stabilized at approximately 650,000 people. On average, Syracuse residents are somewhat older and have slightly lower incomes and poorer health on some measures, such as heart disease, asthma and smoking status, than residents of other metropolitan areas. Compared with other metropolitan areas, Syracuse is less ethnically and racially diverse, with relatively small proportions of black, Latino and Asian residents.

Despite the generally bleak economic climate, people moving from the area have helped keep unemployment in check. In 2008, unemployment averaged 5.5 percent—slightly below the nationwide metropolitan average. The recent recession did not take as heavy a toll in Syracuse as in most other metropolitan areas—a result, many observers said, of the community largely being bypassed by both the initial boom and the subsequent collapse in the credit and housing markets. During the economic downturn, Syracuse unemployment peaked at 9 percent, compared to a 10.5 percent peak across all metropolitan areas nationwide.

Market observers described the Syracuse health market as a paradox in that “it’s a low-cost market…in a high-cost state.” In part, because of the long-term economic downturn, resources such as land and labor tend to be inexpensive in Syracuse. At the same time, New York’s high tax rates and heavy regulation make it an expensive state to do business in. Syracuse health care providers also are more reliant on Medicare and Medicaid revenue than those in many other areas and may have become more efficient to accommodate lower public program payment rates.

Hospital Capacity Enigma: Too Many Beds or Not?

![]() hree of Syracuse’s four general acute-care hospitals are downtown, with Upstate University Hospital and Crouse Hospital literally adjacent to each other, and in close proximity to St. Joseph’s Hospital Health Center. In 2010, inpatient admissions were evenly split among these three hospitals, with each having about 25-percent to 30-percent market share. Community General Hospital, located within the city limits but a few miles from downtown, lagged the other hospitals and saw market share drop from 15 percent in 2007 to below 10 percent in 2010.

hree of Syracuse’s four general acute-care hospitals are downtown, with Upstate University Hospital and Crouse Hospital literally adjacent to each other, and in close proximity to St. Joseph’s Hospital Health Center. In 2010, inpatient admissions were evenly split among these three hospitals, with each having about 25-percent to 30-percent market share. Community General Hospital, located within the city limits but a few miles from downtown, lagged the other hospitals and saw market share drop from 15 percent in 2007 to below 10 percent in 2010.

Currently, none of the hospitals provides a full array of hospital services; each is considered to have distinct market niches. Upstate, part of the State University of New York (SUNY) system, is the sole academic medical center in the community, with the only Level I trauma center and inpatient pediatric hospital. Upstate also is recognized as the leading provider of oncology and most subspecialty care. St. Joseph’s is regarded as the leader in cardiology, cardiovascular surgery and increasingly orthopedics. Crouse has extended its niche—traditionally maternity services—to other areas, including urology. Community was recognized for its orthopedics program in the past, but the hospital’s financial struggles have led observers to question whether it remains dominant in any service lines. Some observers perceived St. Joseph’s and Upstate to be taking steps toward becoming full-service hospitals, but at present, none of the hospitals provides a comprehensive array of services.

The hospitals work together through a longstanding collaborative body, the Hospital Executive Council, to address areas of community-wide interest, such as avoidable hospital readmissions and nursing home capacity for complex patients. By all accounts, however, collaboration ceases when hospital interests diverge—for example, when addressing issues such as possible excess capacity for lucrative services, such as orthopedics and treatment of sleep disorders.

The payer mix at all four hospitals is dominated by public payers, although the breakdown of Medicare vs. Medicaid varies widely. Commercial payments reportedly account for no more than 30 percent to 40 percent of revenues at any hospital. Despite this payer mix and the state’s strong regulatory requirements, all hospitals but Community have continued to do fairly well financially—even throughout the economic downturn—with small but consistently positive operating margins.

Likewise, all hospitals except Community have seen unexpected volume increases in the past couple of years, especially in 2010. This increase was attributed to Community’s struggles, the 2009 closing of A.L. Lee Memorial Hospital in Oswego County, and increased referrals from outlying rural hospitals, together producing an influx of patients, primarily to St. Joseph’s and Upstate. Both hospitals were described as “bursting at the seams,” with occupancy rates consistently near 100 percent.

Both Upstate and St. Joseph’s have undertaken new construction to address capacity constraints and to replace and upgrade older facilities. In 2009, Upstate opened a $150 million patient tower, with more than 200 new private rooms and a children’s hospital—now the only children’s hospital in the community. Upstate also plans to open a new cancer center in 2013. In 2009, St. Joseph’s began a five-year, $220-million project that does not add new overall inpatient capacity but does include a new emergency department, operating rooms, chest pain center and psychiatric unit.

Despite acute capacity constraints at two of Syracuse’s four hospitals, there has been a widely held perception in the state that the Syracuse market is over-bedded. While Crouse and Community do have ample unstaffed beds, the lack of full-service hospitals in the market leads some observers to argue that the real problem lies not in overall capacity, but in a misallocation of beds among the hospitals, leading to capacity constraints in certain services and excess supply in others.

Nevertheless, state authorities have long considered hospital capacity in Syracuse to be excessive. As a result, since the 1990s, numerous consolidation efforts have been made—each ending in failure. In 2006, for example, the Berger Commission—appointed by former Gov. George Pataki—recommended a merger between Upstate and Crouse. On paper, this merger between neighboring hospitals with distinct and complementary service lines appeared to make sense. However, many observers knowledgeable about the market warned of the difficulties of merging two very different management styles and cultures in the two institutions—one public and academic, the other private and community-based—that often expressed antipathy to each other. These issues did, indeed, play a central role in ultimately dooming the 2007 merger attempt. More recently, another proposed merger—between Crouse and Community—also failed. Crouse’s proposal to transfer nearly all acute care to its campus and convert Community to a psychiatric and rehabilitation facility was rejected by the latter’s board in 2010.

The current merger between Upstate and Community was viewed more as an acquisition by Upstate than a merger among equals. Upstate is seeking to expand teaching efforts and accommodate growing patient volumes, at a fraction of the cost of new construction. The estimated cost of the Community acquisition is $20 million plus the cost of updating facilities, while the cost of Upstate’s new patient tower was $150 million. Community is viewing the merger as an opportunity to stem patient outflows and financial losses and to gain capital for infrastructure and technology upgrades. Though the merger has come to fruition, as most observers had expected, issues that have derailed other mergers—the chasm between academic and community cultures, and public and private cultures—still have to be resolved. In anticipation of the merger, some Community-affiliated physicians moved their referrals to Crouse and St. Joseph’s. Upstate changed its medical bylaws to accommodate a voluntary medical staff of private-practice physicians (consistent with Community’s current structure); those not interested in teaching or being in a faculty practice would not have to assume these roles.

Views about the merger’s potential impact on costs were mixed. Some—including executives at the two merging hospitals—suggested that costs will be reduced through greater efficiency, but others expressed concern about the potentially “catastrophic” impact that the acquisition of the lowest-cost hospital by the highest-cost hospital might have on commercial payment rates.

At the time of the site visit, it was widely expected that the merger would take place by mid-2011. True to expectations, the merger was finalized in July 2011 after being approved by Community’s board of directors, the SUNY Board of Trustees, as well as other state authorities, including the attorney general, the comptroller and the Department of Health.

Moderate Increases in Consolidation, Hospital Employment of Physicians

![]() yracuse’s supply of primary care physicians is only slightly lower than the national average for metropolitan areas, but many respondents expressed concern about the adequacy of physician supply going forward. The average age of practicing physicians is high—mid- to late-50s—and there are numerous health system characteristics and broader community characteristics that make physician recruitment a daunting challenge. These factors include low Medicaid payment rates, strong dependence on Medicare payments coupled with low Medicare Advantage penetration, a highly regulated practice environment, a stagnant economy, a cold climate, and high state income taxes.

yracuse’s supply of primary care physicians is only slightly lower than the national average for metropolitan areas, but many respondents expressed concern about the adequacy of physician supply going forward. The average age of practicing physicians is high—mid- to late-50s—and there are numerous health system characteristics and broader community characteristics that make physician recruitment a daunting challenge. These factors include low Medicaid payment rates, strong dependence on Medicare payments coupled with low Medicare Advantage penetration, a highly regulated practice environment, a stagnant economy, a cold climate, and high state income taxes.

The degree of competition in the physician market reportedly was not intense; most respondents described the physician supply as being tight enough for there to be “sufficient work to go around.” However, as previously noted, there is considerable competition and friction between a public and academic culture at Upstate vs. a private and community-based culture elsewhere. There are widely held perceptions—perhaps exaggerated—that Upstate is heavily subsidized by the state and, therefore, not exposed to the same market pressures as private hospitals. In 2010, the state subsidy to Upstate totaled $37 million, or 7 percent of Upstate’s revenues; both the dollar amount of the subsidy and its share of revenues have fallen over time and are expected to decline further because of the state fiscal crisis. There is also some resentment at the “double-dipping” opportunities available to Upstate specialists, with many supplementing their state salaries with earnings from private practice.

Historically, the Syracuse physician market was dominated by small, independent practices. In some specialties, this has remained the case, while in other specialties—such as family practice, orthopedics, urology and oncology—consolidated, single-specialty groups have become the norm. The past three years have seen a continuation of this trend of practice consolidation. Most groups continue to maintain admitting privileges at more than one private hospital, but the hospitals have attempted to entice groups into more exclusive arrangements.

Most consolidated groups continue to emphasize the provision of ancillary services—especially lucrative imaging and clinical laboratory services—as a business strategy, typically pitting them against hospitals. Beginning in 2010, however, reduced Medicare payment for imaging has led to a change in strategy for some physician groups. A notable example is cardiology, where, until very recently, the market’s three cardiology groups had competed aggressively against one another and against hospitals to provide such services as nuclear cardiac imaging. However, reduced Medicare payment has motivated these groups to explore mergers or hospital employment.

Hospitals are slowly ramping up their employment of physicians, although hospital-owned practices still account for a small percentage of physicians overall. A previous experiment with hospital employment in the 1990s was unsuccessful, as lower physician productivity under salaried arrangements ultimately led hospitals to divest most practices. Today, St. Joseph’s employs the most physicians—about 100—which reflects a large increase over the past three years. While other hospitals trail St. Joseph’s in employment, all are pursuing discussions with physician groups. Hospitals have started by buying practices already strongly affiliated with them. As in other markets, the primary objective for hospitals in acquiring practices is to increase exclusive referrals. The primary objective of physicians in being acquired is to ease financial pressures from flat payment rates combined with the rising costs of practicing medicine.

Excellus Faces Challenges

![]() here continued to be little competition in the Syracuse health plan market, with Excellus Blue Cross Blue Shield holding a market share of at least two-thirds of the commercial market, by most estimates. While Excellus is dominant in all market segments, its position is especially commanding in the small-to-mid-sized segments, including the highly regulated, community-rated small-group market of two to 50 lives.

here continued to be little competition in the Syracuse health plan market, with Excellus Blue Cross Blue Shield holding a market share of at least two-thirds of the commercial market, by most estimates. While Excellus is dominant in all market segments, its position is especially commanding in the small-to-mid-sized segments, including the highly regulated, community-rated small-group market of two to 50 lives.

MVP Health Care, a regional plan based in Schenectady, N.Y., continued to run a very distant second to Excellus, with 10- to 15-percent commercial market share. Traditionally strongest in health maintenance organizations (HMOs)—a particular challenge in Syracuse, a market historically resistant to managed care—MVP attempted to diversify its product line by acquiring Rochester-based Preferred Care in 2006. To date, however, MVP had not gained much of a foothold in the preferred provider organization (PPO) market in Syracuse.

The presence of national plans, including Aetna and UnitedHealth Group, tends to “ebb and flow” in the Syracuse market, according to market observers. After withdrawing from the small-to-mid-sized markets in 2010, Aetna has focused solely on large national accounts with operations in Syracuse. United still offered products in all market segments with at least 50 lives but reportedly had lost business to Excellus as a result of uncompetitive pricing.

Over the past few years, the large-group, self-insured market has been the most competitive segment, with national plans and local third-party administrators (TPAs) providing a more vigorous challenge to Excellus. Since the beginning of 2009, Excellus has suffered high-profile setbacks, as some of its most prominent and longstanding local accounts—including Syracuse University, the city of Syracuse, Crouse Hospital and some school districts—defected to POMCO Group, a local TPA. Excellus’ troubles stemmed in part from perceptions that the company is an out-of-touch outsider—with corporate decisions made in Rochester rather than Syracuse. Excellus’ decision to relocate its Syracuse headquarters from downtown to suburban DeWitt was a major blow to the economically depressed downtown business district. The move, seen by many as “a politically tone-deaf act,” as one respondent said, caused local leaders to question Excellus’ commitment to the community and contributed to the defections of major local employers to POMCO. These employers also had grown frustrated by Excellus’ claims data reporting capabilities, which have been described as “severely inadequate”—a result of the company’s reliance on four separate, incompatible data systems dating from the 1980s.

Views were mixed regarding the impact of these high-profile defections from Excellus to POMCO. According to market observers, Excellus and Syracuse University officials have publicly aired opposing views about the impact of the university’s move to POMCO. Excellus suggested that Syracuse University is now paying substantially more in claims, largely because of higher provider payment rates, but university officials countered that they not only avoided negative financial impact and provider network disruptions, but also received better data reporting, as a result of the move. There was near-universal agreement that while Excellus’ dominance has hardly been dented by the loss of a few large local accounts, these defections did serve to highlight Excellus’ limitations and, in turn, focus company attention on improving its community image, customer relations and data-reporting capabilities. Among Excellus’ highest-priority initiatives is the construction of a single claims-processing platform—a project expected to be completed in 2013.

Moderate Cost Sharing Increase

![]() yracuse remains a market where nearly all commercial products feature comprehensive provider networks. Indemnity insurance still persists as an option for many public-sector employees whose benefits are collectively bargained, but respondents noted that indemnity products are virtually indistinguishable from PPOs, because of the breadth of PPO networks and Excellus’ use of a single, community-wide physician fee schedule.

yracuse remains a market where nearly all commercial products feature comprehensive provider networks. Indemnity insurance still persists as an option for many public-sector employees whose benefits are collectively bargained, but respondents noted that indemnity products are virtually indistinguishable from PPOs, because of the breadth of PPO networks and Excellus’ use of a single, community-wide physician fee schedule.

Recent cost pressures—less acute in Syracuse than in many other markets—have not resulted in employer demand for product innovations such as limited-network options. One observer characterized Syracuse insurance products as “a lot of plain vanilla.” The increasing prevalence of wellness features and incentives represents the only benefit design changes that might be considered innovative. Wellness products have become available in every market segment and now include about a quarter of commercial lives. However, within these products, enrollee participation in wellness activities reportedly remained low, despite the fact that most incentives are based on participation in wellness activities rather than achievement of health benchmarks and were considered relatively easy to attain. Some employers paying higher premiums for such products were questioning the return on investment.

While employers in Syracuse—and upstate New York in general—continued to increase employee premium contributions and patient cost sharing at a moderate pace over the past few years, they still provide richer benefits than the national norm, according to benefits consultants. For example, most employers have established different copayment tiers for visits to primary care physicians vs. specialists and increased the copayment dollar amounts, but few employers have moved to percentage-based coinsurance. Similarly, more employers—especially in the smaller-group segments—have moved to consumer-directed health plans (CDHPs)—which include larger deductibles and typically are paired with a tax-advantaged savings account. However, overall CDHP penetration remained relatively modest.

Premium pressures—reportedly more intense downstate than upstate—led New York to pass a 2010 rate review law, which required insurers to submit premium increases for community-rated products—primarily in the individual and small-group markets—to the state’s Department of Insurance (DOI) for approval. In the first round of rate review, which took place in late 2010, DOI decided to limit the scope of review and approve all proposed rate increases below 12.5 percent. As a result, all of Excellus’ proposed increases (9% to 12.5%) were approved, while MVP’s much higher proposed increases—reportedly to correct for severe underpricing—were rejected. Some observers expressed concern about this outcome, noting that if not conducted rigorously—in particular, with careful consideration of each plan’s underlying cost trends—rate regulation might have the unintended effect of reducing already weak plan competition and increasing Excellus’ dominance. Indeed, in 2011, United notified DOI that it planned to pull out of the small-group market as of 2012. United cited both the overall burden of complying with the rate-review process and rejection of proposed rate increases as reasons for withdrawing from this market.

Relations Improve Between Excellus and Providers

![]() ver the past few years, Excellus has focused on—and largely succeeded in—improving provider relationships, which had been contentious. By nearly all accounts, Excellus receives significant discounts compared to other payers but appears to exercise its market leverage with some restraint, particularly in dealing with hospitals—which reportedly were able to obtain increases that consistently exceed medical inflation.

ver the past few years, Excellus has focused on—and largely succeeded in—improving provider relationships, which had been contentious. By nearly all accounts, Excellus receives significant discounts compared to other payers but appears to exercise its market leverage with some restraint, particularly in dealing with hospitals—which reportedly were able to obtain increases that consistently exceed medical inflation.

Despite its dominance of the health plan market, Excellus’ bargaining power is somewhat tempered by the market niches occupied by each of the hospitals—contributing to their must-have status in health plan networks. For many important services, duplication among hospitals is limited—often with two, rather than four, hospitals competing on a given service. For inpatient pediatrics, there is no duplication at all, with Upstate being the sole provider. The Upstate-Community merger, by further removing duplication of hospital services, is widely expected to enhance the negotiating power of the remaining three hospitals.

In contrast to hospitals, physicians have little, if any, leverage against insurers and have seen flat payment rate trends in recent years. This is particularly true of the many physicians who remain in independent practice, but even where physicians have formed large, single-specialty groups, consolidation has resulted in only modestly higher payments. Excellus has moved to a single, community-wide fee schedule for physician payment, so its base rates are the same regardless of practice size. However, large groups are better able to gain additional payments through Excellus’ pay-for-performance program, Rewarding Physician Excellence, which rewards practice infrastructure improvement, such as electronic medical records, as well as performance on process and outcome measures.

For most physicians remaining in independent practice, flat payment rate trends, combined with rising overhead costs, mean that incomes can be maintained only by seeing more patients. Given Syracuse’s small base of affluent patients, dropping out of health plan networks and charging higher fees directly to patients was not considered a viable option for most physicians.

Most Safety Net Providers Faring Well Despite Challenges

![]() ince 2007, New York has expanded its already generous eligibility standards for public insurance programs. As a result, Syracuse’s already low uninsurance rate declined. In 2008, 9.8 percent of Syracuse residents lacked insurance, compared to 14.9 percent in metropolitan areas nationwide. In 2009, even as the recession continued, Syracuse’s uninsurance rate fell to 8.9 percent vs. 15.1 percent nationwide.

ince 2007, New York has expanded its already generous eligibility standards for public insurance programs. As a result, Syracuse’s already low uninsurance rate declined. In 2008, 9.8 percent of Syracuse residents lacked insurance, compared to 14.9 percent in metropolitan areas nationwide. In 2009, even as the recession continued, Syracuse’s uninsurance rate fell to 8.9 percent vs. 15.1 percent nationwide.

Despite the drop in uninsurance, Syracuse safety net providers reported increased demand for services over the last three years. This rising demand likely was caused in part by a shift from private insurance to Medicaid and other public programs, as jobs were lost and some employers dropped insurance coverage. Also, the closure of Oswego County’s A.L. Lee Memorial Hospital shifted demand to the remaining safety net providers in greater Syracuse.

Although there is little coordination among safety net providers, the Syracuse safety net appeared relatively strong and stable, and so far has been able to meet rising demand. The three largest hospitals share the burden of providing inpatient care to low-income people, with each hospital playing a distinct role. Crouse has the largest share of Medicaid patients, largely because it dominates obstetrical and neonatal services. However, the bulk of safety net hospital services—both Medicaid and uncompensated care—is provided by Upstate and St. Joseph’s because of services for which these hospitals are the sole or dominant provider—particularly pediatrics, trauma and tertiary care for Upstate and psychiatry and cardiology for St. Joseph’s. Upstate and St. Joseph’s also maintain outpatient clinics primarily serving low-income people. Community plays a smaller safety net role because of its financial struggles and more modest market share overall, as well as its less central location.

In Onondaga County, where the city of Syracuse is located, the major provider of primary care for low-income people is Syracuse Community Health Center (SCHC), the county’s only federally qualified health center (FQHC)—eligible for both federal grant funding and enhanced Medicaid payment rates. SCHC has expanded and has 15 locations, including seven school-based sites. The Onondaga County safety net is also served by the county health department, whose services are largely limited to public health, and a couple of small, independent free clinics. The much smaller Oswego County, which accounts for less than one-fifth of the population of greater Syracuse, also has its own FQHC, Pulaski Health Center, operated by Northern Oswego County Health Services, Inc.

Most safety net providers were in sound financial health, having managed to maintain modest positive operating margins through a combination of funding from the 2009 federal American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), higher revenues from patients with public insurance and increased efficiencies. As in other communities, FQHCs used ARRA funding to increase capacity and update infrastructure. FQHCs also have benefited from the state Department of Health’s Medicaid payment reforms reallocating funds from inpatient to outpatient services. Going forward, however, state budget woes pose serious challenges to safety net providers. FQHCs’ ability to maintain expanded capacity in the face of both expected state funding cuts and ARRA funding expiration was in doubt. Under even greater threat were non-FQHC clinics (such as the Westside Family Health Center—part of St. Joseph’s outpatient network—serving a predominantly minority population), which have neither federal grants nor enhanced Medicaid reimbursement to buffer them from state funding reductions.

Views regarding access to care in the safety net were mixed. Many respondents believed primary care resources to be relatively good in Onondaga County, given the presence and expanded capacity of the county’s large FQHC, SCHC, as well as the clinics operated by Upstate and St. Joseph’s. Others suggested access was inadequate, with a shortage of primary care physicians willing to serve low-income people. To alleviate this shortage, some providers have hired more mid-level professionals—a strategy supported by the presence of two local training programs for nurse practitioners and physician assistants. Access to dental care, while still difficult, reportedly has improved over the last several years. More private dental practices were serving Medicaid patients in Oswego County, and Upstate, St. Joseph’s and the FQHCs all operate dental clinics. However, safety net access to specialty services continued to be severely inadequate, particularly for anesthesiology, psychiatry and all pediatric specialties. Some specialists reportedly refuse to accept referrals from clinics unless non-English-speaking patients are accompanied by interpreters.

Expanded Medicaid Eligibility, Streamlined Enrollment

![]() s noted earlier, in 2007, New York began implementing eligibility expansions that put the state ahead of virtually all other states in generosity of public insurance coverage. These expansion efforts included increasing income eligibility as follows: Medicaid for childless adults up to 100 percent of poverty, Child Health Plus (CHP) up to 400 percent of poverty ($88,200 for a family of four in 2010), and Family Health Plus (FHP, for parents and young adults) up to 160 percent of poverty, as well as raising the maximum eligibility age for young adults in FHP to 20. With these program expansions and the slow economy combining to make more people eligible, public insurance enrollment in greater Syracuse grew from 98,000 in 2007 to 122,000 by late 2010—an increase of nearly 25 percent.

s noted earlier, in 2007, New York began implementing eligibility expansions that put the state ahead of virtually all other states in generosity of public insurance coverage. These expansion efforts included increasing income eligibility as follows: Medicaid for childless adults up to 100 percent of poverty, Child Health Plus (CHP) up to 400 percent of poverty ($88,200 for a family of four in 2010), and Family Health Plus (FHP, for parents and young adults) up to 160 percent of poverty, as well as raising the maximum eligibility age for young adults in FHP to 20. With these program expansions and the slow economy combining to make more people eligible, public insurance enrollment in greater Syracuse grew from 98,000 in 2007 to 122,000 by late 2010—an increase of nearly 25 percent.

Along with the eligibility expansions, New York took aggressive action to simplify and streamline public insurance enrollment and renewal—a task made easier by the 2007 formation of the Department of Health’s Office of Health Insurance Programs, which became the single state agency responsible for all public insurance programs. New York has long been a leader among states in facilitating public insurance enrollment and renewal, but its policies had been selectively applied only to certain eligible groups. Since 1990, for example, pregnant women in Medicaid have received “presumptive eligibility,” where those appearing to be eligible for Medicaid are granted immediate, short-term coverage while their formal applications are processed. Since the late 1990s, children in CHP also have been granted presumptive eligibility, as well as eligibility for shortened application forms and the ability to apply by mail rather than in person. While children in Medicaid were not eligible for those features, since the late 1990s, they have received 12 months of continuous eligibility regardless of family income fluctuations.

Over the past three years, the state has taken steps to replace this confusing patchwork system with policies that apply more uniformly across Medicaid, CHP and FHP populations. In 2008, for example, the state implemented presumptive eligibility for children’s Medicaid enrollment, and in 2010, the state eliminated the requirement for pregnant women to complete in-person interviews. The state also eliminated other barriers such as fingerprint screening and county variation in income eligibility levels. Going forward, New York plans to replace its current county-based system of enrollment and renewal for public insurance with a single statewide enrollment center in 2011. This new center, featuring a mail-in renewal system, was expected to facilitate renewal in particular.

Throughout the economic downturn and state fiscal crisis, New York’s generous expanded eligibility for public insurance remained untouched, in part because of the federal requirements that states to maintain Medicaid eligibility levels to receive ARRA funding. But optional benefits under Medicaid, CHP and FHP largely escaped cuts as well.

Over the past few years, New York implemented major changes in Medicaid payment methods and rates—changes aimed at slowing cost growth overall and at making rates fairer and more efficient. Changing inpatient payment methodology from diagnosis related groups, or DRGs, to all patient refined-diagnosis elated groups, or APR-DRGs—with the latter designed to account more accurately for severity of illness and risk of mortality—allowed the state to reduce inpatient payments substantially in 2007 and 2009. These savings were reallocated to ambulatory care, for which Medicaid payment rates had been frozen for roughly a decade. In 2008, New York began implementing ambulatory patient groups, or APGs—which adjust base payments to reflect intensity of services—as the new outpatient payment method. This change resulted in average per visit fees increasing by 55 percent for hospital outpatient clinics, 72 percent for ambulatory surgery and 48 percent for emergency department visits, compared to previous fee-for-service rates. Among Syracuse hospitals, this payment reallocation appeared to pose the greatest challenges for Crouse, which provides significantly fewer outpatient services than St. Joseph’s or Upstate.

Until recently, New York’s Medicaid payment rates to physicians had been among the lowest in the nation. For example, office visits for new and existing patients had been paid at a flat rate of $30 per visit, regardless of complexity. To rectify this situation and encourage broader provider participation, in 2009, Medicaid began increasing fees to physicians, nurse practitioners and other providers by an average of 40 percent—bringing rates up to 74 percent of Medicare rates. The state also introduced add-on fees of 10 percent each for after-hours and weekend visits and office-based physicians practicing in shortage areas.

More than four in five Medicaid enrollees in greater Syracuse were enrolled in managed care, which is mandatory for most enrollees except nursing home residents and those dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. In 2008, New York began a four-year phase-in of risk-adjusted capitation payment to Medicaid managed care plans, replacing the former method of regional cost-based payment. However, there has been little, if any, innovation in how Syracuse plans pay providers; fee-for-service payment for physicians, based on the Medicaid fee schedule, is still universal. Budget deficits led the state to cut payment rates to Medicaid plans over the past two years, including a cut in quality incentive payments.

With New York’s many Medicaid payment reforms having been phased in over a number of years, respondents found it difficult to speak to the impact of these payment changes on providers’ financial health or their willingness to serve low-income populations. It also was unclear whether there was a net reduction in Medicaid payment rates overall or just a redistribution from inpatient to outpatient services. This reallocation, along with the implementation of risk adjustment, was widely viewed in a positive light, as being fairer and more efficient than previous methods. At the same time, there was widespread concern about statewide Medicaid spending—already the highest in the nation, both per capita and in total expenditures—continuing to grow at a brisk pace. This growth reflected, in part, the state’s emphasis on expanding eligibility and easing enrollment and renewal even as the economy and the budget crisis worsened.

Anticipating Health Reform

![]() ew York was well ahead of most other states on several key dimensions of preparedness for national health reform. As described earlier, the state already implemented major coverage expansions between 2007 and 2010. In the commercial insurance market, plans already faced heavy state regulation, with provisions for minimum medical loss ratios and coverage of preventive care, pre-existing conditions and dependents. In the small-group market of two-50 lives, New York’s current regulations—requiring pure community rating, with no premium adjustments allowed for individual characteristics—were more stringent than national reform provisions. Having already implemented many of its own coverage expansions and insurance market reforms, New York does face the challenge of melding existing policies with new federal requirements.

ew York was well ahead of most other states on several key dimensions of preparedness for national health reform. As described earlier, the state already implemented major coverage expansions between 2007 and 2010. In the commercial insurance market, plans already faced heavy state regulation, with provisions for minimum medical loss ratios and coverage of preventive care, pre-existing conditions and dependents. In the small-group market of two-50 lives, New York’s current regulations—requiring pure community rating, with no premium adjustments allowed for individual characteristics—were more stringent than national reform provisions. Having already implemented many of its own coverage expansions and insurance market reforms, New York does face the challenge of melding existing policies with new federal requirements.

While the state may be ahead of the curve, Syracuse was widely regarded as lagging in preparations for reform. Consistent with a community that never adopted highly consolidated or integrated care delivery, there has been relatively little interest in payment innovations or accountable care organizations (ACOs). In fact, some providers expressed concern that, as specified in the federal reform law, the Medicare shared savings model—which accepts an ACO’s base spending level as the appropriate baseline for determining spending targets—would penalize the Syracuse community’s already relatively efficient providers. Respondents pointed out that, despite little formal care delivery integration, Syracuse ranks high in efficiency according to the Dartmouth Atlas analysis of Medicare spending.

Expected Medicare payment cuts under reform were a major concern for Syracuse hospitals, which are heavily reliant on public payers. Many respondents did not believe that coverage expansions would mitigate the rate reductions, as payment rates under the insurance exchanges were expected to fall between Medicaid and Medicare rates. For Upstate, which currently receives sizable disproportionate share hospital, or DSH, payments to help cover the costs of caring for low-income patients, the reform legislation’s DSH payment cuts are a particular concern.

Issues to Track

- How successfully will the combined Upstate-Community entity merge two disparate cultures? To what extent will the merger alleviate Upstate’s capacity constraints? What will be the merger’s impact on competition among hospitals and leverage with health plans?

- How will payment changes under health reform affect the financial health of hospitals? Will health reform accelerate movement by physicians into larger practices and/or hospital employment?

- What impact will New York’s premium rate review law have on health plan competition and insurance premiums in the individual and small-group markets?

- How will New York’s fiscal crisis affect eligibility, benefits, provider payments and overall spending for Medicaid and other public insurance programs?

- To what extent will the safety net be able to maintain its expanded capacity after federal stimulus funds expire? How will funding for the area’s two FQHCs fare under health reform?

- How adequate is provider capacity—particularly primary care capacity—for meeting demand from the newly insured under health reform?

Background Data

| Syracuse Demographics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Syracuse Metropolitan Area |

Metropolitan Areas 400,000+ Population | |

| Population, 20091 | 646,084 | |

| Population Growth, 5-Year, 2004-20092 | -0.5% | 5.5% |

| Age3 | ||

| Under 18 | 22.3% | 24.8% |

| 18-64 | 64.3% | 63.3% |

| 65+ | 13.4% | 11.9% |

| Education3 | ||

| High School or Higher | 88.5% | 85.4% |

| Bachelor’s Degree or Higher | 28.1% | 31.0% |

| Race/Ethnicity4 | ||

| White | 85.8%* | 59.9% |

| Black | 7.2% | 13.3% |

| Latino | 2.6%# | 18.6% |

| Asian | 1.9% | 5.7% |

| Other Races or Multiple Races | 2.4% | 4.2% |

| Other3 | ||

| Limited/No English | 2.1%# | 10.8% |

# Indicates a 12-site low. |

||

| Economic Indicators | ||

|---|---|---|

| Syracuse Metropolitan Area |

Metropolitan Areas 400,000+ Population | |

| Individual Income less than 200% of Federal Poverty Level1 | 29.3% | 26.3% |

| Household Income more than $50,0001 | 49.1% | 56.1% |

| Recipients of Income Assistance and/or Food Stamps1 | 10.1% | 7.7% |

| Persons Without Health Insurance1 | 9.8% | 14.9% |

| Unemployment Rate, 20082 | 5.5% | 5.7% |

| Unemployment Rate, 20093 | 8.0% | 9.2% |

| Unemployment Rate, August 20104 | 7.6% | 10.0% |

Sources: |

||

| Health Status | ||

|---|---|---|

| Syracuse Metropolitan Area1 |

Metropolitan Areas 400,000+ Population2 | |

| Chronic Conditions | ||

| Asthma | 17.9% | 13.4% |

| Diabetes | 8.0% | 8.2% |

| Angina or Coronary Heart Disease |

7.5% | 4.1% |

| Other | ||

| Overweight or Obese | 59.0% | 60.2% |

| Adult Smoker | 21.5% | 18.3% |

| Self-Reported Health Status Fair or Poor |

13.1% | 14.1% |

|

||

| Health System Characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Syracuse Metropolitan Area |

Metropolitan Areas 400,000+ Population | |

| Hospitals1 | ||

| Staffed Hospital Beds per 1,000 Population | 2.8 | 2.5 |

| Average Length of Hospital Stay (Days) | 6.4* | 5.3 |

| Health Professional Supply | ||

| Physicians per 100,000 Population2 | 245 | 233 |

| Primary Care Physicians per 100,000 Poplulation2 | 79 | 83 |

| Specialist Physicians per 100,000 Population2 | 166 | 150 |

| Dentists per 100,000 Population2 | 56 | 62 |

Average monthly per-capita reimbursement for beneficiaries enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare3 |

$564# | $713 |

* Indicates a 12-site high. 1 American Hospital Association, 2008 2 Area Resource File, 2008 (includes nonfederal, patient care physicians) 3 HSC analysis of 2008 county per capita Medicare fee-for-service expenditures, Part A and Part B aged and disabled, weighted by enrollment and demographic and risk factors. See www.cms.gov/MedicareAdvtgSpecRateStats/05_FFS_Data.asp. |

||

Funding Acknowledgement

The 2010 Community Tracking Study and resulting Community Reports were funded jointly by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the National Institute for Health Care Reform. Since 1996, HSC researchers have visited the 12 communities approximately every two to three years to conduct in-depth interviews with leaders of the local health system.