Physicians Key to Health Maintenance Organization Popularity in Orange County

Community Report No. 10

August 2011

Laurie E. Felland, Genna R. Cohen, Paul B. Ginsburg, Elizabeth A. November, Ha T. Tu, Tracy Yee

In June 2010, a team of researchers from the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC), as part of the Community Tracking Study (CTS), visited Orange County, Calif., to study how health care is organized, financed and delivered in that community. Researchers interviewed more than 45 health care leaders, including representatives of major hospital systems, physician groups, insurers, employers, benefits consultants, community health centers, state and local health agencies, and others. The Orange County metropolitan area comprises the same borders as Orange County.

The extent of health plan delegation of financial risk and utilization management to physicians caring for health maintenance organization (HMO) enrollees makes Orange County a somewhat unusual market. Although preferred provider organizations (PPOs) and new product designs have gained some traction in recent years, the HMO model remains popular among Orange County employers and consumers because of cost advantages and a wide choice of providers. Physician organizations, including large, multispecialty medical groups and independent practice associations (IPAs), provide the practice infrastructure to support care coordination and have fared well under capitated, or fixed per-member, per-month, payments. Indeed, the so-called delegated model, where physicians assume the financial risk and associated care management of patients from health plans, is thriving in Orange County despite predictions to the contrary.

At the same time, hospital and physician interest in tighter affiliations has grown. While hospitals must work within California’s restrictions on physician employment by forming foundations, they, nonetheless, are aligning with physicians to secure patient referrals, support specialty-service lines and prepare for national health reform. Indeed, expected payment reforms will likely provide incentives to integrate care delivery and expand opportunities for physicians to assume risk for new patient populations.

Key developments include:

- After coexisting for years in somewhat distinct areas of Orange County, hospitals are impinging on each other’s territories in the wealthier southern and coastal parts of the county to attract well-insured patients.

- Kaiser Permanente, an integrated delivery system and closed-panel HMO, has attained a higher profile in the market by building a new hospital and becoming less reliant on contracts with other providers for enrollees’ care.

- Safety net providers and stakeholders have increased their focus on obtaining federal dollars to expand capacity and programs, including developing a managed system of care to help transition uninsured residents into Medi-Cal—the state’s Medicaid program—or subsidized insurance coverage under national health reform.

- More Diverse Than Thought

- Unconsolidated Hospital and Health Plan Markets

- Physicians Coming Together

- Hospital-Physician Alignment

- Balanced Provider-Health Plan Leverage

- Geographic Competition Heats Up

- HMOs Remain Robust and Kaiser’s Presence Expands

- Safety Net Broadens

- CalOptima Regains Footing

- Transitioning to Insurance

- Issues to Track

- Background Data and Funding Acknowledgement

More Diverse Than Thought

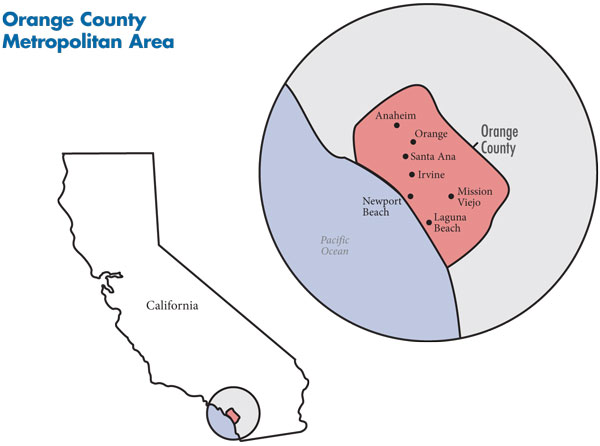

![]() ommonly perceived as a wealthy, southern California coastal community, Orange County does have a high proportion of households with annual incomes above $50,000—67.5 percent vs. 56.1 percent for large metropolitan areas on average in 2008. Still, this community of more than 3 million people is quite diverse along socioeconomic lines. The Pacific coast and southern part of the county, including Irvine, Newport Beach, Laguna Beach and Mission Viejo, are home to more affluent residents, while the northern parts of the county, including the two largest cities—Santa Ana and Anaheim—have greater concentrations of low-to-middle income residents (see map below). The area is home to high-tech firms and a large service sector and many small employers with low-wage workers. The unemployment rate has been slightly below the average for large metropolitan areas, rising during the economic downturn to 9.5 percent by June 2010, compared to 9.8 percent in other metropolitan areas on average.

ommonly perceived as a wealthy, southern California coastal community, Orange County does have a high proportion of households with annual incomes above $50,000—67.5 percent vs. 56.1 percent for large metropolitan areas on average in 2008. Still, this community of more than 3 million people is quite diverse along socioeconomic lines. The Pacific coast and southern part of the county, including Irvine, Newport Beach, Laguna Beach and Mission Viejo, are home to more affluent residents, while the northern parts of the county, including the two largest cities—Santa Ana and Anaheim—have greater concentrations of low-to-middle income residents (see map below). The area is home to high-tech firms and a large service sector and many small employers with low-wage workers. The unemployment rate has been slightly below the average for large metropolitan areas, rising during the economic downturn to 9.5 percent by June 2010, compared to 9.8 percent in other metropolitan areas on average.

The county is racially and ethnically diverse as well, with Census data indicating increasing diversity over the past decade. As of 2008, Orange County had almost triple the percentage of Asian residents and almost double the percentage of Latino residents of the average metropolitan area. The challenges new and undocumented immigrants face gaining health insurance may contribute to the county’s higher-than-average uninsurance rate (17.8% vs. 15.1% among metropolitan areas in 2009).

Significant demographic and socioeconomic variation across the county contributes to both the structure and competitive dynamics of the health care delivery system. One respondent described the county as “two separate places separated by the [Costa Mesa] freeway. Northern Orange County has a large immigrant population…and a lot of blue-collar workers. Southern Orange County is more upscale—a wealthier market.” As a result, provider expansion and competition, as well as health plan competition, center on the coastal and southern parts of the county, where well-insured patients tend to live.

Unconsolidated Hospital and Health Plan Markets

![]() he Orange County hospital sector is relatively unconsolidated, with three prestigious nonprofit systems holding about half of the total market share, and a number of additional systems and independent hospitals sharing the rest. St. Joseph Health System (SJHS) is the largest system, with more than 20 percent of inpatient admissions and four hospitals: flagship St. Joseph Hospital and St. Jude Medical Center in the north-central part of the county and Mission Hospital-Mission Viejo and Mission Hospital-Laguna Beach in the coastal and southern areas (SJHS has additional hospitals elsewhere in California and beyond). Hoag operates two hospitals: Hoag Memorial Hospital Presbyterian in Newport Beach and Hoag Hospital Irvine. MemorialCare Health System, which also has hospitals in Los Angeles County, operates three hospitals in coastal and southern Orange County: its flagship facility, Saddleback Memorial-Laguna Hills, plus Saddleback Memorial-San Clemente and Orange Coast Memorial. In 2009, the system sold its Anaheim hospital to AHMC Healthcare Inc., a for-profit system based in Los Angeles.

he Orange County hospital sector is relatively unconsolidated, with three prestigious nonprofit systems holding about half of the total market share, and a number of additional systems and independent hospitals sharing the rest. St. Joseph Health System (SJHS) is the largest system, with more than 20 percent of inpatient admissions and four hospitals: flagship St. Joseph Hospital and St. Jude Medical Center in the north-central part of the county and Mission Hospital-Mission Viejo and Mission Hospital-Laguna Beach in the coastal and southern areas (SJHS has additional hospitals elsewhere in California and beyond). Hoag operates two hospitals: Hoag Memorial Hospital Presbyterian in Newport Beach and Hoag Hospital Irvine. MemorialCare Health System, which also has hospitals in Los Angeles County, operates three hospitals in coastal and southern Orange County: its flagship facility, Saddleback Memorial-Laguna Hills, plus Saddleback Memorial-San Clemente and Orange Coast Memorial. In 2009, the system sold its Anaheim hospital to AHMC Healthcare Inc., a for-profit system based in Los Angeles.

Location and reputation allow the three major hospital systems to attract-higher income and better-insured patients. These hospitals benefit financially from being so-called must-have providers, meaning health plans must include them in their networks to offer insurance products attractive to employers and consumers. Because of their negotiating clout with health plans, they can maintain high margins on privately insured patients. These hospitals also have weathered the costs of complying with seismic retrofitting requirements and the loss of insured patients during the recession—mainly for elective procedures—fairly well, although not without streamlining operations and pursuing other cost-containment strategies. Many of the capacity constraints that stressed these systems in the past—namely insufficient inpatient beds and nurses to meet state nurse-to-patient staffing ratios—appeared to have subsided, partly because of the economic downturn.

Lacking a county hospital for decades, many low-income people in Orange County have relied on the University of California Irvine Medical Center (UCI) for care. As an academic medical center, UCI also provides advanced specialty services for the broader community, although UCI does not have the same stature and clout with health plans as other UC hospitals, such as UCLA and UCSF. Plagued by highly publicized problems with the quality of patient care, UCI, nonetheless, has fared relatively well financially in recent years, according to state hospital finance data. Children’s Hospital of Orange County (CHOC) in the city of Orange is the main safety net hospital for children. The majority of CHOC’s patients are publicly insured, but the hospital also treats many privately insured children and has posted small but positive margins.

Orange County has a relatively large number of for-profit hospitals. Although Tenet’s presence in the county has waned as it sold off hospitals, its three remaining hospitals still have an aggregate market share of about 10 percent—almost as much as MemorialCare. Also, physician investors purchased some of the struggling Tenet and other community hospitals in the mid-to-late 2000s, which are now part of the for-profit Integrated Healthcare Holdings Inc. (IHHI) and Prime Health Care systems, which each own four hospitals in Orange County.

While the for-profits’ financial situation appeared to improve over the past few years, IHHI and Prime continued to struggle with lower commercial payment rates and their high proportion of Medicaid patients; in fact, respondents named some of these for-profits as safety net hospitals. California’s costly seismic retrofitting requirements reportedly contributed to Tenet’s decision to sell some hospitals, and some respondents noted concern that IHHI and Prime might close hospitals in response to future state enforcement of seismic compliance schedules, possibly straining capacity at remaining hospitals.

Similar to the hospital sector, no single health insurer is dominant in Orange County. Anthem Blue Cross is the largest plan, with about one-third of the commercial enrollees in the market. Market observers reported Anthem’s strengths include the ability to handle large, national accounts and offer a breadth of products in every commercial market segment that results in “a menu [of products] that includes what any buyer might want,” according to a broker. Overall, Anthem products typically have a price advantage because Anthem’s size allows it to negotiate better discounts from providers. Other key health plans include Kaiser Foundation Health Plan Inc.—a division of Kaiser Permanente—Blue Shield of California and UnitedHealth Group. Other national and regional plans include Aetna, CIGNA and Health Net, all of which have small or niche presences for certain types of employers or geographic areas.

Physicians Coming Together

![]() ecause of the prevalence of the delegated model for physician services (see box below for more about the delegated model), Orange County has various types of physician organizations that are able to assume financial risk for patients’ care, and in many cases, provide physicians with practice infrastructure and administrative support. These organizations include independent practice associations, independent medical groups and hospital-affiliated medical foundations.

ecause of the prevalence of the delegated model for physician services (see box below for more about the delegated model), Orange County has various types of physician organizations that are able to assume financial risk for patients’ care, and in many cases, provide physicians with practice infrastructure and administrative support. These organizations include independent practice associations, independent medical groups and hospital-affiliated medical foundations.

Many primary care physicians (PCPs) and specialists remain in solo or small, physician-owned practices but become members of one or more IPAs, which contract with plans as a single entity for capitated HMO patients. There are numerous IPAs in Orange County. Monarch HealthCare is the largest, with more than 2,600 member physicians and relationships with hospitals across the county to provide services for its HMO patients. In contrast, Greater Newport IPA, with approximately 500 physicians, contracts exclusively with Hoag.

Orange County has some larger medical groups, including Kaiser’s Southern California Permanente Medical Group and UCI’s affiliated faculty practice, each with more than 500 physicians. While two of the largest physician-owned practices in the market were Talbert Medical Group, a multispecialty group with more than 100 physicians, and Bristol Park, with over 80 PCPs, both are now part of larger provider organizations.

Indeed, as the costs of running a practice outpace payment rate increases, individual physicians and those in small groups have been under increased pressure to join larger physician organizations. As summarized by a market observer, “Most physicians aren’t doing as well [financially] as they used to.” Some smaller practices are merging with one another, which some respondents thought may just forestall their need to join larger groups or IPAs. Larger-scale physician organizations are better equipped to cope with pressure on reimbursement rates and support implementation of health information technology (HIT), which is viewed as essential to care coordination. As a physician organization representative explained, “We can’t put [HIT] on hold. We have to weather the revenue decreases and spend capital on robust HIT.”

Although physicians in independent practices often belong to multiple IPAs to attract more HMO patients, there were signs that physicians were maintaining relationships with fewer IPAs. The IPA model has stabilized to the point that physicians see less need to belong to multiple IPAs, and a few respondents indicated that some physicians are reducing their IPA affiliations to curb administrative burden. As one observer noted, “The stability of the IPAs has made [physicians] comfortable with fewer choices; before when they [IPAs] went out of business [an issue about a decade ago], [physicians] didn’t want to have too many eggs in one basket. Now they are okay with being more exclusive.” As a result, competition for physician allegiance among IPAs appeared to be intensifying.

The Delegated Model in Orange County In Orange County, the dominant type of HMO is a network—as opposed to a closed-panel—gatekeeper model. Plans typically delegate financial risk for some services, care management and other responsibilities, including utilization management and physician credentialing, to the physician organizations responsible for treating the enrollee. Through this delegated model, HMOs (commercial, Medi-Cal and Medicare Advantage) pay the physician organization on a capitated basis for primary and specialty physician services and outpatient diagnostic services, including imaging, as well as non-specialty prescription drugs in some cases. While the scope of services included under capitation has decreased over time to exclude hospital services, one health plan respondent reported that some physician groups want to expand the scope again, potentially taking on risk for hospital costs. The delegated model remains strong in Orange County despite past predictions of its demise. Some respondents believed that plans that were previously managed locally but moved out of state—Anthem is now headquartered in Indianapolis and PacifiCare was acquired by Minneapolis-based UnitedHealth Group—would abandon this model to be consistent with how they pay providers elsewhere, but this has not occurred. Because physicians have continued to do well financially under the delegated model, they remain proponents of its use. |

Hospital-Physician Alignment

![]() ecause California’s corporate practice of medicine law prohibits hospitals from directly employing physicians, some hospitals have formed foundations as a way to align with physicians. The long-time St. Joseph Heritage Healthcare medical practice foundation includes physician groups and IPAs affiliated with its Orange County hospitals, encompassing more than 1,800 physicians. The recently formed MemorialCare Medical Foundation is substantially smaller in size with approximately 100 physicians in two Orange County practices, including Bristol Park. Both foundations also include other physician organizations outside the county.

ecause California’s corporate practice of medicine law prohibits hospitals from directly employing physicians, some hospitals have formed foundations as a way to align with physicians. The long-time St. Joseph Heritage Healthcare medical practice foundation includes physician groups and IPAs affiliated with its Orange County hospitals, encompassing more than 1,800 physicians. The recently formed MemorialCare Medical Foundation is substantially smaller in size with approximately 100 physicians in two Orange County practices, including Bristol Park. Both foundations also include other physician organizations outside the county.

Hospitals attract physicians to join a group or IPA that contracts with the foundation, which then directs patients covered under the foundation’s HMO risk contracts to these physicians for care. A foundation can provide physicians significant infrastructure support. In the case of medical groups, the foundation purchases the practice assets and medical records, employs non-physician staff, and leases facilities. Foundations also provide administrative services, such as physician credentialing and claims processing, and HIT. Some physicians have exclusive relationships with a hospital foundation, while others do not because their patients are spread across too wide a geographic area, requiring them to retain admitting privileges at multiple facilities.

Some efforts to develop or expand foundations have met with physician resistance. Physicians fear losing their independence and, if they don’t join, that they will not receive equal treatment. For example, specialists may be concerned about not receiving patient referrals from PCPs in the foundation and favorable operating room schedules.

Also, the state requirements for setting up a foundation are complex and costly, leaving the foundation model a less viable option for financially weaker hospitals. A hospital foundation must be operated by a nonprofit corporation, have at least 40 physicians and surgeons representing no less than 10 specialties, conduct medical research, and have board members representing physicians, the hospital and the community.

With both hospitals and physician organizations interested in aligning with more physicians, competition has heated up between the foundation-model entities and the independent large groups and IPAs. For example, Monarch HealthCare, an IPA, created a medical group (Premier Physicians Medical Group) to offer physicians seeking employment an alternative to joining a group affiliated with a foundation.

Another way that hospitals are aligning with physicians is through ambulatory surgical centers (ASCs). As Medicare facility reimbursement for some specialty services has declined, physicians have looked to hospitals to purchase these facilities or form joint ventures. If established as a hospital outpatient department, these facilities typically obtain higher Medicare payment rates.

Further, the likelihood of new payment systems and incentives under national health reform to integrate care delivery is spurring greater interest in hospital-physician alignment. The IPAs and medical groups in this market are expected to be at the forefront of forming accountable care organizations (ACOs) because these organizations have long assumed risk and developed mechanisms to coordinate care and reduce unnecessary hospital admissions. In this market, ACOs may provide physicians with an opportunity to assume some financial risk for PPO and Medicare fee-for-service patients to capture financial rewards for providing care efficiently using already-developed systems.

Some of the larger health care organizations in Orange County are engaged in early ACO activity. To date, Monarch, HealthCare Partners and Anthem have collaborated with the Brookings-Dartmouth ACO Learning Network to pilot an ACO for select Anthem fully insured PPO patients. Also, Hoag and Greater Newport IPA have joined the nationwide Premier provider alliance to help them establish an ACO. According to recent media reports, Blue Shield and St. Joseph Health System are collaborating to start an ACO in January 2012.

Balanced Provider-Health Plan Leverage

![]() he balance of negotiating power between hospitals and health plans appeared relatively equal. As one health plan executive said, “Orange County, thankfully, is a more competitive area than a lot of California [where dominant hospital systems garner significant rate increases].” The more prestigious hospital systems—namely Hoag and St. Joseph’s—reportedly have rough parity in negotiating power with Anthem, the largest health plan, while Anthem seemed to have some leverage over other hospitals to negotiate lower rates. Although must-have hospitals gained relatively large rate increases in recent years, hospital respondents reported that the rate of increase has slowed, particularly since the recession. Further, hospital respondents expected rate negotiations to become increasingly difficult as insurers try to curb increases, especially because of the continued slow economy and expected pressure on premiums for products sold through the state-based benefit exchange starting in 2014.

he balance of negotiating power between hospitals and health plans appeared relatively equal. As one health plan executive said, “Orange County, thankfully, is a more competitive area than a lot of California [where dominant hospital systems garner significant rate increases].” The more prestigious hospital systems—namely Hoag and St. Joseph’s—reportedly have rough parity in negotiating power with Anthem, the largest health plan, while Anthem seemed to have some leverage over other hospitals to negotiate lower rates. Although must-have hospitals gained relatively large rate increases in recent years, hospital respondents reported that the rate of increase has slowed, particularly since the recession. Further, hospital respondents expected rate negotiations to become increasingly difficult as insurers try to curb increases, especially because of the continued slow economy and expected pressure on premiums for products sold through the state-based benefit exchange starting in 2014.

Compared to hospitals, physician groups and IPAs reportedly had somewhat less negotiating leverage with health plans. Large groups and IPAs can negotiate better rates than smaller groups and independent physicians, although antitrust rules prevent most IPAs from negotiating payment rates for PPO enrollees. An implication of this is that, according to health plan respondents, HMO provider rates have been increasing more rapidly than PPO rates. The physician organizations affiliated with Hoag—Greater Newport IPA—and St. Joseph—St. Joseph Heritage Healthcare medical practice foundation—were named by plan respondents as those with the most negotiating power, along with Monarch.

Geographic Competition Heats Up

![]() s a strategy to secure and expand their commercially insured patient base and gain leverage over health plans, Orange County hospitals are intensifying competition along geographic lines, particularly in the southern coastal communities and the growing, upper-middle class Irvine area. After coexisting peacefully for years, the major hospital systems are expanding into each other’s turf by adding or taking over inpatient and outpatient facilities. For example, St. Joseph’s moved into the coastal area in 2009 by purchasing Adventist Health’s South Coast Medical Center—now Mission Hospital-Laguna Beach.

s a strategy to secure and expand their commercially insured patient base and gain leverage over health plans, Orange County hospitals are intensifying competition along geographic lines, particularly in the southern coastal communities and the growing, upper-middle class Irvine area. After coexisting peacefully for years, the major hospital systems are expanding into each other’s turf by adding or taking over inpatient and outpatient facilities. For example, St. Joseph’s moved into the coastal area in 2009 by purchasing Adventist Health’s South Coast Medical Center—now Mission Hospital-Laguna Beach.

Other than a hospital in Anaheim, Kaiser previously lacked sufficient inpatient capacity and contracted with other hospitals to serve members in more convenient locations. Kaiser also sent members with certain specialty needs, for example, open heart surgery or radiation oncology, to non-Kaiser facilities in Orange County or Kaiser facilities in neighboring San Diego or Los Angeles. In May 2008, however, Kaiser opened a hospital in Irvine to attract new health plan enrollees from the more affluent southern part of the county. Kaiser subsequently ended its contract with Tenet’s Irvine Regional Hospital and Medical Center (IRHMC). Also, Kaiser is replacing its 30-year-old Anaheim hospital with an updated, larger facility in 2012 and will bring additional services in house.

Another component of Kaiser’s strategy to minimize contracting with non-Kaiser providers included hiring more subspecialists at its Southern California Permanente Medical Group. Indeed, other providers’ longstanding concerns about Kaiser’s advantage in recruiting physicians appeared to have come true. Although Orange County has more physicians per capita than the average metropolitan area, physician organizations face challenges recruiting additional physicians because of the area’s high cost of living. Kaiser reportedly offers physicians better salaries, benefits and more regular work hours. Kaiser’s commitment to HIT, including an electronic health record that is the centerpiece of its care coordination and quality improvement efforts, is also viewed as a draw for physicians.

A highly prestigious hospital and formidable competitor whose presence had been limited to Newport Beach, Hoag followed Kaiser’s entry into Irvine by obtaining the IRHMC facility from Tenet, which had closed it after losing significant patient volume when Kaiser ended its contract. Hoag renovated and reopened the facility as Hoag Hospital Irvine in September 2010, a general acute care hospital with a focus on orthopedic procedures and a few other specialty services. Approximately half of the hospital’s 154 beds are dedicated to orthopedic patients and more operating rooms were added. The new Hoag facility poses a direct competitive threat to St. Joseph’s profitable orthopedic service line.

Until a few years ago, geography divided the physician group and IPA market as well. Monarch, traditionally dominating the southern part of the county, has reached northward in search of new affiliates. Based in Los Angeles, HealthCare Partners Medical Group—a large multispecialty group with an IPA—expanded into northern Orange County in 2005 and acquired Talbert Medical Group in May 2010.

HMOs Remain Robust and Kaiser’s Presence Expands

![]() ompared to other markets, tightly managed HMOs hold a large proportion of the commercial health plan market in Orange County, which is related to the prevalence of the delegated model. Among HMO products, the network model is dominant, while Kaiser’s closed-panel HMO historically had relatively small market share, particularly compared to Kaiser’s larger presence in Los Angeles and northern California. However, in recent years, Kaiser’s enrollment has grown to about 20 percent of privately insured people in Orange County, while network HMOs lost some ground to Kaiser and to PPOs. Still, it remained common for large employers to offer an HMO alongside PPO options and market share between HMOs and PPOs appeared roughly balanced.

ompared to other markets, tightly managed HMOs hold a large proportion of the commercial health plan market in Orange County, which is related to the prevalence of the delegated model. Among HMO products, the network model is dominant, while Kaiser’s closed-panel HMO historically had relatively small market share, particularly compared to Kaiser’s larger presence in Los Angeles and northern California. However, in recent years, Kaiser’s enrollment has grown to about 20 percent of privately insured people in Orange County, while network HMOs lost some ground to Kaiser and to PPOs. Still, it remained common for large employers to offer an HMO alongside PPO options and market share between HMOs and PPOs appeared roughly balanced.

A number of factors contribute to the HMO’s appeal in Orange County. Although not as extensive as PPO networks, non-Kaiser HMO networks are still relatively broad and include the vast majority of hospitals and large physician organizations in the county. Moreover, unlike in some other markets, HMOs in Orange County still offer a substantial price advantage over PPOs. Use of the delegated model helps advance care management strategies, which contain costs. As one benefits consultant explained, “[The HMO price advantage] is driven by extremely efficient HMOs, which is driven by the capitated delivery model.”

Most health plans in Orange County experienced stagnant or declining commercial enrollment as the recession led to the loss of jobs and employer-sponsored coverage. More than 60,000 commercially insured people in the market, or almost 3 percent, lost coverage between 2008 and 2009, according to Census data. Also, health care benefits for workers in the private sector—which has little union presence—eroded. The gap in the comprehensiveness of benefits between large and small-to-medium-sized employers has grown, with the latter raising patient cost sharing more dramatically.

Indeed, in recent years, health plans faced growing pressure to contain insurance premium increases for employers and their workers. Health plans in the market have tinkered with product designs that lower premiums or increase cost sharing in different ways. Growing in popularity are PPOs with pared-down benefits, HMOs with deductibles or narrow networks, and consumer-driven health plans (CDHPs) characterized by a high-deductible plan tied to a health savings account or health reimbursement arrangement. CDHP and narrow-network HMO enrollment growth are strongest in the individual and small-group markets, where cost concerns are greatest. Even so, narrow-network HMO products in Orange County tend not to have extremely limited provider choice because state regulation requires HMOs to demonstrate that their networks provide adequate access. This regulatory requirement essentially limits the narrowness of these products. Subject to less-stringent regulation, PPOs and CDHPs can be more flexible with their networks and leaner with their benefit designs to keep premiums down. Still, CDHP penetration is lower in Orange County than in many other markets, perhaps because HMOs hold a slight premium advantage over CDHPs.

Kaiser’s deductible and consumer-driven HMO product lines—aimed at the more cost-conscious segments of the market—reportedly are popular. Also, an increasing number of employers reportedly are moving to Kaiser-only coverage rather than splitting their business among carriers. Indeed, Kaiser’s increased health plan enrollment and new insurance products, along with its expanded provider capacity, likely make the organization a growing competitive threat to hospitals, large physician organizations and health plans, alike. Some market observers expected Kaiser to expand significantly over the next few years, while others thought Kaiser will maintain its status as a niche player because of its unique integrated delivery system, relatively limited product offerings, and longstanding difficulty competing for national accounts against plans with stronger PPO and third-party administrator capabilities.

Safety Net Broadens

![]() emand for charity care grew in Orange County during the recession, and the safety net expanded in response. Safety net hospitals reported increasing uncompensated care spending over the last few years, and patient volume at community clinics reportedly rose significantly. In particular, safety net providers experienced growth in “unexpected uninsured” patients, referring to more middle-income people who recently lost their jobs and health insurance. As one clinic director reported, “The volume of calls [from people] trying to become our patients has drastically increased.”

emand for charity care grew in Orange County during the recession, and the safety net expanded in response. Safety net hospitals reported increasing uncompensated care spending over the last few years, and patient volume at community clinics reportedly rose significantly. In particular, safety net providers experienced growth in “unexpected uninsured” patients, referring to more middle-income people who recently lost their jobs and health insurance. As one clinic director reported, “The volume of calls [from people] trying to become our patients has drastically increased.”

Services to low-income people (Medi-Cal enrollees and the uninsured) also are more dispersed among hospitals. Respondents indicated that, beyond its operation of two federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), UCI has pulled back somewhat from its longstanding role as the main safety net hospital, for example, by reportedly resisting referrals of uninsured patients from health centers and clinics. Reportedly, other hospitals have proactively assumed more responsibility—St. Joseph was cited by many as a safety net leader. Both St. Joseph and Hoag support clinics for low-income people and provide those patients with specialty and hospital services. These systems’ strong financial performance helps support their safety net role. In addition, the Children’s Hospital of Orange County operates clinics that serve low-income children throughout the community and is expanding capacity on campus.

In total, approximately 20 community health centers and other clinic organizations operating in more than 50 locations provide outpatient care to low-income residents. These centers collaborate on a range of issues through the Coalition of Orange County Community Health Centers. Many of these organizations expanded during the economic downturn, although some faced financial strains and reduced staff. The state’s dire budget situation led to decreased support for providers, including elimination of adult dental services in Medi-Cal, delayed state Medi-Cal payments and elimination of the Expanded Access to Primary Care funding to pay providers for preventive services.

However, expansions in the Medical Services Initiative (MSI)—a county program for uninsured adults with incomes below 200 percent of the federal poverty level, or $41,100 for a family of four in 2010—helped. The program reimburses clinics, physicians and hospitals for treating the uninsured. The state’s Health Care Coverage Initiative, which operates under a Medicaid waiver, allowed MSI to provide more comprehensive care and to expand enrollment, not only for people with an immediate medical need, but a small group of healthy people as well. Enrollment grew by about a third between 2008 and 2010, reaching about 45,000 of the estimated 500,000 uninsured people in the county.

Additionally, county officials and safety net providers are increasingly savvy about obtaining federal dollars to support community health centers. With only UCI’s FQHCs previously, Orange County lagged many other communities in taking advantage of federal grants and enhanced Medicaid reimbursement available to FQHCs. Respondents provided various rationales for what prompted the county to catch up in attaining FQHC status for community clinics: a visit by then-President George W. Bush, who encouraged local investment in the federal application process; increased collaboration through the clinic consortium; and physicians and clinic directors moving to Orange County who had experience with FQHCs elsewhere. As one recalled, “When I came [to Orange County] six years ago, people didn’t even know what an FQHC was; it wasn’t on the table.”

Currently, five health centers—with multiple sites—are FQHCs. Additional clinics are working to gain federal status, including some clinics currently with FQHC look-alike status, which allows them to receive enhanced Medicaid reimbursement but not federal grants. One of the newer FQHCs is AltaMed Health Care Services, a large FQHC based in Los Angeles that expanded into Orange County in recent years. Four of AltaMed’s 10 medical and dental sites in Orange County represent an acquisition of a struggling FQHC. However, safety net respondents are concerned that AltaMed’s high proportion of Medi-Cal patients has left other centers and clinics to care for a disproportionate number of uninsured patients.

Safety net respondents noted relatively high willingness of physicians in private practice to treat MSI and Medi-Cal patients. Despite low reimbursement rates from Medi-Cal and the MSI program, respondents reported relatively large and growing physician networks in both programs, with many of the private physician organizations participating. Specifically, the boost in MSI reimbursement rates reportedly helped broaden the MSI provider network by about two-thirds between 2008 and 2010—more than the growth in enrollment. Even after a subsequent partial rollback of the MSI reimbursement hike because of budget shortfalls, reimbursement now approximates Medi-Cal rates, and physician participation reportedly remained quite stable.

The enhanced willingness of physicians to participate in these programs also might be linked to physicians’ loss of privately insured patients during the recession, which may have improved the relative attractiveness of Medi-Cal and MSI reimbursement. In fact, as FQHCs expanded, competition reportedly increased between the health centers and physicians for MSI and Medi-Cal patients and how the latter are assigned to providers by CalOptima, the county Medi-Cal agency. With the participation of extensive private physician networks, Medi-Cal enrollees may have better access to private primary care and specialist physicians than in many other communities.

CalOptima Regains Footing

![]() n an effort to control costs, California has continued to place more Medi-Cal enrollees in managed care arrangements, which vary by county. Orange County and four other counties directly administer the program as a “county organized health system.” Established in 1993, Orange County’s agency—CalOptima—has been hailed in the state and elsewhere as a sound and innovative managed care model. In fact, in addition to the populations included under mandatory managed care by the state, CalOptima also administers care for other Medi-Cal enrollees, including those dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, as well as Children’s Health Insurance Program enrollees. Medi-Cal enrollment in Orange County has increased steadily—from approximately 300,000 in December 2007 to about 378,000 people by July 2011.

n an effort to control costs, California has continued to place more Medi-Cal enrollees in managed care arrangements, which vary by county. Orange County and four other counties directly administer the program as a “county organized health system.” Established in 1993, Orange County’s agency—CalOptima—has been hailed in the state and elsewhere as a sound and innovative managed care model. In fact, in addition to the populations included under mandatory managed care by the state, CalOptima also administers care for other Medi-Cal enrollees, including those dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, as well as Children’s Health Insurance Program enrollees. Medi-Cal enrollment in Orange County has increased steadily—from approximately 300,000 in December 2007 to about 378,000 people by July 2011.

CalOptima has turned around financially since 2007, when the agency had to dip into reserves, creating concern about the sustainability of this managed care model. In 2010, however, CalOptima boasted its highest reserves ever at $150 million. Although the state provided CalOptima with slight per-enrollee rate increases during that period, the agency continued to run a deficit on Medi-Cal. Most of CalOptima’s financial gains came from its Medicare special needs plan—OneCare—established in 2005, as well as a recovery from initial losses after taking on financial risk for hospital services.

With its recovery, CalOptima used reserves to continue providing some optional benefits cut by the state and pay providers when the state delayed payments to plans. As one provider said, “CalOptima works really hard to try to insulate providers from some of the changes at the state level.” Still, market observers are concerned that the agency’s finances remain fragile, particularly given expected payment changes to Medicare special needs plans and the ongoing state budget deficit. Indeed, the state’s fiscal year 2011-12 budget includes a 10-percent reduction in Medi-Cal payment rates to many providers, increased copayments for Medi-Cal enrollees, as well as an annual cap of seven physician/clinic visits that enrollees can obtain without physician approval.

Transitioning to Insurance

![]() ealth care providers in Orange County are working with county officials and consultants on a “Managed System of Care” for low-income people. Initiated before the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act but in anticipation of health reform, the goal is to provide low-income, uninsured people with a more-integrated safety net system to address immediate needs and help them adapt to an insurance environment, ultimately transitioning them into Medi-Cal or subsidized private coverage in 2014. This system will provide comprehensive care, from primary to hospital care, coordinated through a medical-home model. To achieve this, the community plans to continue expanding FQHC capacity and build on MSI’s latest efforts to better manage and coordinate care, which include a nurse-advice line, after-hours urgent care, an electronic specialty-referral system and a chronic-disease registry.

ealth care providers in Orange County are working with county officials and consultants on a “Managed System of Care” for low-income people. Initiated before the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act but in anticipation of health reform, the goal is to provide low-income, uninsured people with a more-integrated safety net system to address immediate needs and help them adapt to an insurance environment, ultimately transitioning them into Medi-Cal or subsidized private coverage in 2014. This system will provide comprehensive care, from primary to hospital care, coordinated through a medical-home model. To achieve this, the community plans to continue expanding FQHC capacity and build on MSI’s latest efforts to better manage and coordinate care, which include a nurse-advice line, after-hours urgent care, an electronic specialty-referral system and a chronic-disease registry.

Whether the Managed System of Care will be run through the county, CalOptima or a new public/private entity is yet to be determined, but funding is expected to come from multiple sources. These include the Health Funders Partnership of Orange County (a group of 15 private foundations that merged their funds in 1999), hospitals (that expect their participation to ultimately yield more insured patients and reduce charity care costs), existing state and local government funds, as well as new federal dollars, particularly through the state’s Medi-Cal waiver, called the California Bridge to Reform. The goal is to have 85,000 uninsured people in the Managed System of Care by 2013—starting with the current MSI enrollees—and potentially develop the new safety net structure into an ACO.

Issues to Track

- Will physicians continue to consolidate? Will the hospital foundation model continue to grow, or will physicians prefer joining independent medical groups and IPAs as a way to retain some autonomy? What impact will these changes have on patients’ access to physicians and hospitals and overall health care costs?

- Will ACOs flourish in this market and improve patient care quality while controlling costs? To what extent will the experience in this market be an indicator of the potential for ACOs elsewhere given the historical prevalence of capitation in this market?

- Will geographic competition lead to excess capacity of health care services and rising costs in the wealthier parts of the county, while creating service gaps in lower-income areas?

- Will increasing cost concerns contribute to the continuing expansion of Kaiser and a resurgence of network-model HMOs? What role will limited-benefit and limited-network products play?

- Will CalOptima maintain financial stability and access to services in the face of ongoing state budget deficits?

- How adequate is provider capacity—particularly primary care capacity—for meeting demand from the newly insured under health reform?

- Will the Managed System of Care effectively transition uninsured people into insurance coverage and more coordinated care?

Background Data

| Orange County Demographics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Orange County Metropolitan Area |

Metropolitan Areas 400,000+ Population | |

| Population, 20091 | 3,026,786 | |

| Population Growth, 5-Year, 2004-20092 | 2.4% | 5.5% |

| Age3 | ||

| Under 18 | 25.4% | 24.8% |

| 18-64 | 63.2% | 63.3% |

| 65+ | 11.4% | 11.9% |

| Education3 | ||

| High School or Higher | 82.1% | 85.4% |

| Bachelor’s Degree or Higher | 35.4% | 31.0% |

| Race/Ethnicity4 | ||

| White | 46.2% | 59.9% |

| Black | 1.6%# | 13.3% |

| Latino | 33.8% | 18.6% |

| Asian | 16.0%* | 5.7% |

| Other Races or Multiple Races | 2.4% | 4.2% |

| Other3 | ||

| Limited/No English | 21.7% | 10.8% |

# Indicates a 12-site low. |

||

| Economic Indicators | ||

|---|---|---|

| Orange County Metropolitan Area |

Metropolitan Areas 400,000+ Population | |

| Individual Income less than 200% of Federal Poverty Level1 | 25.2% | 26.3% |

| Household Income more than $50,0001 | 67.5%* | 56.1% |

| Recipients of Income Assistance and/or Food Stamps1 | 3.9%# | 7.7% |

| Persons Without Health Insurance1 | 17.0% | 14.9% |

| Unemployment Rate, 20082 | 5.3% | 5.7% |

| Unemployment Rate, 20093 | 9.0% | 9.2% |

| Unemployment Rate, June 20104 | 9.5% | 9.4% |

# Indicates a 12-site low. |

||

| Health Status1 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Orange County Metropolitan Area |

Metropolitan Areas 400,000+ Population | |

| Chronic Conditions | ||

| Asthma | 12.0% | 13.4% |

| Diabetes | 6.8% | 8.2% |

| Angina or Coronary Heart Disease |

2.7%# | 4.1% |

| Other | ||

| Overweight or Obese | 57.8% | 60.2% |

| Adult Smoker | 11.3% | 18.3% |

| Self-Reported Health Status Fair or Poor |

14.8% | 14.1% |

# Indicates a 12-site low. |

||

| Health System Characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Orange County Metropolitan Area |

Metropolitan Areas 400,000+ Population | |

| Hospitals1 | ||

| Staffed Hospital Beds per 1,000 Population |

1.8 | 2.5 |

| Average Length of Hospital Stay (Days) |

4.7 | 5.3 |

| Health Professional Supply | ||

| Physicians per 100,000 Population2 |

254 | 233 |

| Primary Care Physicians per 100,000 Poplulation2 |

96 | 83 |

| Specialist Physicians per 100,000 Population2 |

158 | 150 |

| Dentists per 100,000 Population2 |

99* | 62 |

| Average monthly per-capita reimbursement for beneficiaries enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare3 |

$738 | $713 |

* Indicates a 12-site high. Sources:1 American Hospital Association, 2008 2 Area Resource File, 2008 (includes nonfederal, patient care physicians) 3 HSC analysis of 2008 county per capita Medicare fee-for-service expenditures, Part A and Part B aged and disabled, weighted by enrollment and demographic and risk factors. See www.cms.gov/MedicareAdvtgSpecRateStats/05_FFS_Data.asp. |

||

Funding Acknowledgement

The 2010 Community Tracking Study and resulting Community Reports were funded jointly by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the National Institute for Health Care Reform. Since 1996, HSC researchers have visited the 12 communities approximately every two to three years to conduct in-depth interviews with leaders of the local health system.