Denver: Competitive Insurance Market Awaits National Health Reform

RWJF Reform Community Report

June 2013

Laurie E. Felland, Emily Carrier, Amanda E. Lechner, Rebecca Gourevitch

![]() espite waiting until nearly the 11th hour to approve a Medicaid expansion, Colorado is at the forefront of preparing for national health reform relative to many states, according to a new Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC) study of the Denver region’s commercial and Medicaid insurance markets (see Data Source). Colorado was among the first states to pass legislation creating a state-run health insurance exchange. Even before the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) passed, Colorado was proactive in reforming the small-group insurance market and expanding Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) to more low-income adults and children. Although initially undecided about the full Medicaid expansion scheduled for Jan. 1, 2014, Democratic Gov. John Hickenlooper, backed by a broad coalition of health care providers and advocates, pushed the state Legislature for approval.

espite waiting until nearly the 11th hour to approve a Medicaid expansion, Colorado is at the forefront of preparing for national health reform relative to many states, according to a new Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC) study of the Denver region’s commercial and Medicaid insurance markets (see Data Source). Colorado was among the first states to pass legislation creating a state-run health insurance exchange. Even before the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) passed, Colorado was proactive in reforming the small-group insurance market and expanding Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) to more low-income adults and children. Although initially undecided about the full Medicaid expansion scheduled for Jan. 1, 2014, Democratic Gov. John Hickenlooper, backed by a broad coalition of health care providers and advocates, pushed the state Legislature for approval.

Still, similar to other markets, Denver-area health plan executives, benefits consultants, brokers and others expressed concerns about the market’s readiness for open enrollment in the exchange on Oct. 1. Top concerns include the uncertainty about the impact of health reform on risk selection and premium costs. Market observers also predicted changes in employer health benefit strategies as they attempt to maintain affordable coverage. Key factors likely to influence how national health reform plays out in the Denver area include:

- No dominant insurer. Three national for-profit insurers—Anthem, Cigna and UnitedHealth Group—plus Kaiser Permanente largely divide the commercial insurance market with competition focused mainly on price.

- Hospital negotiating clout. The area’s four hospital systems reportedly have significant negotiating leverage over payment rates, which health plan respondents believed contributes to higher insurance premiums. This leverage may be growing as hospital systems buttress their position by, for example, employing physicians, upgrading facilities, and expanding their geographic reach by building new facilities and affiliating with other hospitals.

- Pared back employee benefits. Employers are embracing high-deductible health plans, adopting defined-contribution strategies and, most recently, adopting limited-physician networks to help moderate rising premiums. However, the commercial market does not appear to be moving toward innovative provider payment arrangements as a cost-control strategy.

- More Medicaid provider accountability. In the wake of significant Medicaid enrollment growth and the earlier demise of risk-based Medicaid managed care, Colorado has adopted an Accountable Care Collaborative model. Under the approach, health plan or provider entities—known as Regional Care Collaborative Organizations, or RCCOs—are responsible for linking Medicaid enrollees to health care and social services in a coordinated manner, with the goal of improving health outcomes and reducing costs for the state. Down the road, respondents expected RCCOs to assume financial risk for Medicaid enrollees’ care and possibly operate in the state insurance exchange.

- Significant plan interest in the exchange. Notwithstanding considerable uncertainty about setting premiums, the four large carriers currently serving the individual and small-group markets, along with possible new market entrants, are expected to participate in the exchange.

- Possible rate shock. Respondents are concerned that new ACA regulations—particularly requirements for more comprehensive benefits—will drive up premiums, especially for young, healthy people in the market. If many forgo coverage, health plans likely will attract sicker-than-average enrollees—known as adverse selection—in the exchange.

- Redoubled cost-control strategies. In response to stricter limits on patient cost sharing and requirements for more comprehensive coverage, employers increasingly are expected to explore new ways to control costs. This may include offering plans with less choice of providers and possibly defined-contribution approaches where employees receive a fixed amount to purchase coverage on their own.

Table of Contents

Market Background

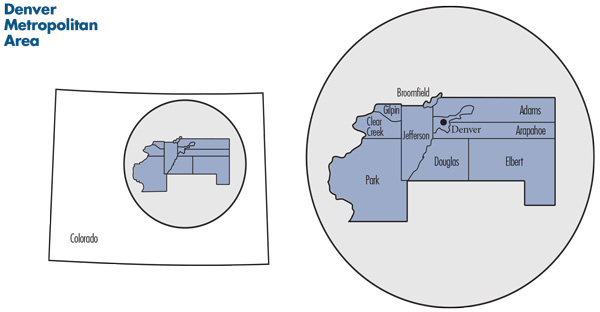

![]() s Colorado’s capital, Denver is at the heart of the state’s most populous metropolitan area along the northern Front Range of the Rocky Mountains. The 2.6 million residents of the Denver metropolitan statistical area reside in 10 counties: Denver, Broomfield, Adams, Arapahoe, Elbert, Douglas, Jefferson, Park, Gilpin and Clear Creek (see map).

s Colorado’s capital, Denver is at the heart of the state’s most populous metropolitan area along the northern Front Range of the Rocky Mountains. The 2.6 million residents of the Denver metropolitan statistical area reside in 10 counties: Denver, Broomfield, Adams, Arapahoe, Elbert, Douglas, Jefferson, Park, Gilpin and Clear Creek (see map).

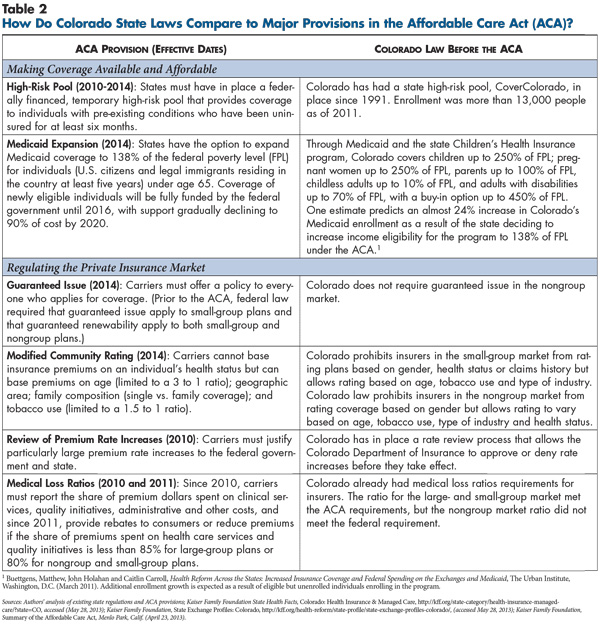

The Denver region has enjoyed a relatively strong economy. The unemployment rate tracked slightly below the U.S. average before and after the 2007-2009 recession, and residents earn slightly higher incomes than the average metropolitan area (see Table 1). Denver reportedly was sheltered somewhat from the Great Recession because the area did not experience a real estate boom in the mid-2000s, which spared the region from the housing collapse that many other metropolitan areas suffered. In addition, Denver does not have a large manufacturing base, which may have allowed the region to fare better than areas that lost many manufacturing jobs.1

The region has attracted many young and healthy people. Between 2005 and 2010, Denver’s population grew 8.5 percent, almost double the rate of the average U.S. metropolitan area. Denver-area residents are younger than other metropolitan areas on average—the median age was 33, about 4 years less than the national median.2 Also, Denver residents have a lower prevalence of heart disease, diabetes and overall fair/poor health status than the national average, and Colorado is the only state in the nation where the obesity rate remains less than 20 percent.3

Much of the recent population growth can be attributed to Latino immigrants moving to the area. Latinos comprised almost half of Denver’s overall population increase from 2000-2010.4 By 2010, 22.5 percent of the population was Latino, compared with 16.4 percent nationwide.

Socioeconomic conditions vary across the Denver region. While low-income residents historically were concentrated in the city of Denver, respondents reported that many lower-income people have moved to the suburbs, especially Aurora, Northglenn and parts of Englewood, raising the average income level in the city of Denver. Indeed, the suburban population is increasingly ethnically diverse, with more Latinos and blacks moving from the city center.5

The Denver economy is characterized by many small and mid-sized employers, particularly in the service, technology, energy, health care and telecommunications sectors. More than half (53%) of Colorado workers are employed by small firms with fewer than 50 employees, compared to 47 percent nationwide.6 Many Denver firms have scaled back health benefits since the late-1990s when competition for skilled workers was high during the economic boom. Since then, the slower economy and a relatively young, healthy employment pool have enabled firms to offer less-comprehensive coverage, and more recently, the Great Recession and rising health care costs have led many firms to trim benefits further.

State Prepares for Reform

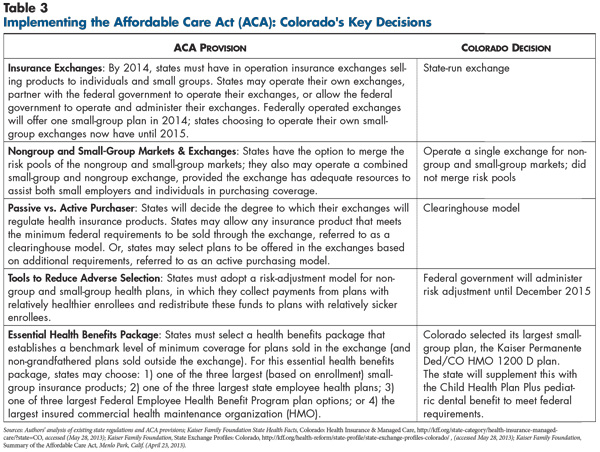

![]() olorado has long been relatively proactive about regulating the private insurance market and expanding public coverage for low-income people, advancing the state toward the coverage goals later outlined in the ACA. Following enactment of the ACA, both then-Gov. Bill Ritter (D) and Hickenlooper supported elements of reform, and in June 2011, the state passed legislation to create a state-run health insurance exchange, named Connect for Health Colorado. Although the costs of expanding Medicaid concerned state legislators, Hickenlooper successfully pushed the Legislature in May 2013 to approve the full Medicaid expansion scheduled for Jan. 1, 2014.

olorado has long been relatively proactive about regulating the private insurance market and expanding public coverage for low-income people, advancing the state toward the coverage goals later outlined in the ACA. Following enactment of the ACA, both then-Gov. Bill Ritter (D) and Hickenlooper supported elements of reform, and in June 2011, the state passed legislation to create a state-run health insurance exchange, named Connect for Health Colorado. Although the costs of expanding Medicaid concerned state legislators, Hickenlooper successfully pushed the Legislature in May 2013 to approve the full Medicaid expansion scheduled for Jan. 1, 2014.

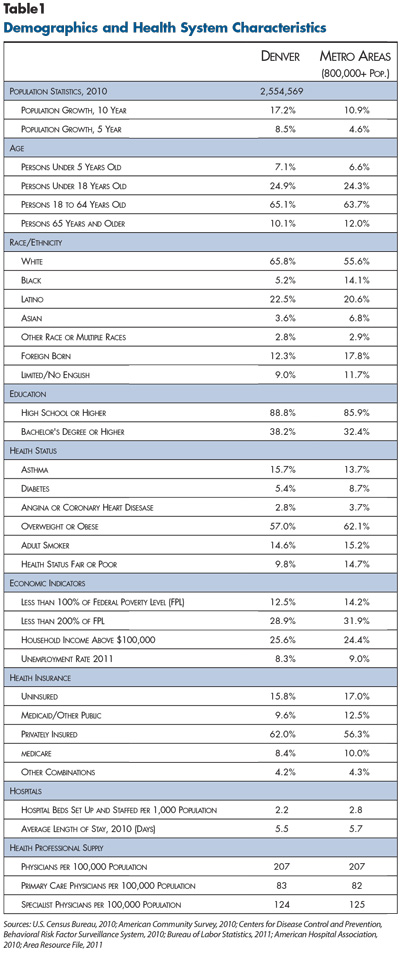

Commercial insurance regulation. While Colorado currently falls in the middle of states in terms of regulation of the individual—or nongroup—and small-group insurance markets, it began reforming these markets several decades ago. In 1994, the state implemented guaranteed issue and some rating restrictions and more recently tightened regulation of the nongroup and small-group health insurance markets—the state defines the small group-market as groups with 1-50 workers to include self-employed individuals. Carriers in both the nongroup and small-group markets can vary premiums based on age, tobacco use and type of occupation/industry but not on gender. Since 2009, small-group plans have been subject to modified community rating regulations that prohibit basing premiums on claims experience or health status. However, nongroup plans are not barred from rating based on health status. Colorado has 30 mandated benefits—a moderate number compared to other states—although Colorado’s mandated benefits include some of the costlier services, such as mental health parity for small groups and comprehensive autism treatment.7 Similar to most states, premium increases in the nongroup and small-group markets are subject to state review and approval.

Beginning in 2014, carriers in Colorado will have to comply with additional federal requirements under the ACA. For example, the law prohibits premium rating based on health status in the nongroup market (see Table 2).

The state also has operated a high-risk pool—CoverColorado—since 1991 for people who cannot get coverage in the nongroup market because of pre-existing conditions. With approximately 13,000 enrollees as of 2010, the high-risk pool is funded by a variety of sources, including member premiums, a fee on health insurance and stop-loss carriers, and the state unclaimed property fund.

Brokers serve as key intermediaries between insurers and small employers in the market. One respondent described Denver as a “broker-driven marketplace” with carriers relying on brokers to help promote products. Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield, for example, sells small-group products exclusively through brokers. In contrast, brokers reportedly play a limited role in the nongroup market.

Medicaid and CHIP expansions. Colorado has long been proactive in expanding coverage for low-income children and adults. In 1992, Colorado launched a program called the Colorado Child Health Plan (CHP), which preceded the federal Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) launched in 1997. CHP was rolled into the federal program and renamed Child Health Plan Plus. By 2006, then-Gov. Bill Owens (R) signed legislation creating the Blue Ribbon Commission for Health Care Reform, which was charged with examining how Colorado might cover the uninsured and address growing health care costs. Following the commission’s 2008 report, the 2009 Colorado Health Care Affordability Act increased Medicaid and CHIP eligibility. CHIP income eligibility increased from 205 percent of poverty to 250 percent for children and pregnant women, and the state created a Medicaid buy-in option for disabled individuals up to 450 percent of poverty. Parents with incomes up to the federal poverty level (FPL) and adults without children up to 10 percent of poverty became eligible for coverage (the law initially covered childless adults up to the poverty level, but budget pressures led the state to drop eligibility to 10 percent of FPL). The state used a lottery to enroll childless adults, with 10,000 initially gaining Medicaid coverage. As openings become available, eligible people on the waiting list are enrolled. All people remaining on the waiting list will gain coverage on Jan. 1, 2014, through the federal Medicaid expansion. Because Colorado’s Taxpayer Bill of Rights restricts government spending,8 the Medicaid and CHIP expansions were financed through a new hospital fee, which generates federal matching funds through a Medicaid waiver.

These public insurance expansions coincided with the recession, and Colorado experienced 30 percent growth in Medicaid enrollment between December 2007 and the end of 2009—from approximately 380,000 to almost 500,000 enrollees—a dramatic increase compared to the national average of just less than 14 percent during the same period.9 By March 2013, Medicaid enrollment reached approximately 700,000 people in Colorado. Respondents suggested that streamlined enrollment processes, including an online application portal, and more effective centralized outreach in the Denver area contributed to the enrollment increase.

A Divided Commercial Insurance Market

![]() ost Denver residents with commercial insurance are covered by one of four carriers—Anthem, Cigna, UnitedHealth Group and Kaiser Permanente—each with almost 20 percent market share. Cigna reportedly is prominent in the large, self-insured market—but gained entrée to the small-group market with the 2008 purchase of Great-West Healthcare—while United, Kaiser and Anthem have a greater presence in the small-group and nongroup markets. Humana and a new entrant, California-based SeeChange Health, are relatively minor players in the small-group market. While Anthem, Cigna and United reportedly charge similar premiums overall, some respondents reported that United holds a slight price advantage. Kaiser was consistently described as offering premiums 10 percent to 15 percent lower than other insurers.

ost Denver residents with commercial insurance are covered by one of four carriers—Anthem, Cigna, UnitedHealth Group and Kaiser Permanente—each with almost 20 percent market share. Cigna reportedly is prominent in the large, self-insured market—but gained entrée to the small-group market with the 2008 purchase of Great-West Healthcare—while United, Kaiser and Anthem have a greater presence in the small-group and nongroup markets. Humana and a new entrant, California-based SeeChange Health, are relatively minor players in the small-group market. While Anthem, Cigna and United reportedly charge similar premiums overall, some respondents reported that United holds a slight price advantage. Kaiser was consistently described as offering premiums 10 percent to 15 percent lower than other insurers.

Apart from Kaiser, the main carriers’ products are reportedly quite similar. “I’d say 90 percent of employers, when they look at the insurance companies [other than Kaiser], think they all look the same,” one benefits consultant said. “Employers don’t see distinguishing characteristics across the carriers. They are buying based on price. There isn’t a network differentiation, and there isn’t a product differentiation.” As in other markets, smaller employers are seen as more price sensitive than large ones, and products aimed at the small-group market tend to compete mainly on price.

Indeed, without a dominant health insurer, hospitals reportedly have significant negotiating leverage over health plans. Health plan executives reported that hospital market power was concentrated among four systems—HealthONE (HCA), Exempla Healthcare, Centura Health and University of Colorado Health. Together these four systems—although University is relatively small among the four—have three-quarters of the inpatient discharges in the market, and respondents reported the systems have considerable leverage over payment rates. Respondents also pointed to Denver hospitals’ ability to obtain other favorable contract terms from carriers, such as covering the full amount—rather than just a portion—of medical claims above a certain cost (i.e. outlier claims) as a sign of their leverage.

Respondents noted the still limited but growing trend of hospital employment of physicians and other hospital-physician affiliations as adding to hospitals’ market clout. One health plan executive reported that approximately one-fifth of physicians the insurer contracts with are now hospital employees. Cardiologists and oncologists in particular are shifting the services they provide from freestanding settings to hospital settings as they become employed, which could be motivated by Medicare payment policy that provides higher reimbursement in hospital outpatient settings.

The top insurers’ relatively equal market position reportedly results in hospitals providing similar discounts across carriers. Respondents expected hospital systems’ leverage to continue to grow as hospitals expand their geographic reach, for example, by moving facilities out of Denver to more-affluent suburbs and by affiliating with previously independent hospitals. In a key example, the University system entered a joint operating agreement with Poudre Valley Health System, with the new organization, University of Colorado Health, extending from Colorado Springs in the south to Laramie, Wyo., in the north.

Although hospital systems are affiliating with physicians, health plan respondents doubted whether these partnerships are prepared to accept financial risk for the populations they serve. Indeed, commercial health plans have not yet entered into accountable care organizations (ACOs)—arrangements where groups of providers assume responsibility for the costs and quality of care for a defined population of patients. One physician-led Medicare Pioneer ACO, Physician Health Partners, operates in the market.

Trimming Benefits

![]() n recent years, most employers have increased workers’ share of premium contributions and adopted leaner benefits to moderate premium growth. Benefits consultants reported that large employers typically contribute 65 percent to 75 percent of employee premiums, with small employers contributing similar or slightly smaller shares. Some small employers have shifted to a defined-contribution model, in which they give employees a fixed amount toward health benefits.

n recent years, most employers have increased workers’ share of premium contributions and adopted leaner benefits to moderate premium growth. Benefits consultants reported that large employers typically contribute 65 percent to 75 percent of employee premiums, with small employers contributing similar or slightly smaller shares. Some small employers have shifted to a defined-contribution model, in which they give employees a fixed amount toward health benefits.

Preferred provider organization (PPO) products remain popular, but high-deductible health plans (HDHPs) are rapidly gaining popularity in both the large- and small-group markets. Respondents estimated current HDHP penetration ranges from nearly 20 percent for larger firms to more than 30 percent for smaller firms. One survey found that 53 percent of all Colorado employers’ plans have deductibles of $1,000 or more for individuals, compared to 34 percent of employers nationally.10 Denver respondents reported that deductibles of $3,000 or more for individuals are common in the small-group market.

Most insurers have offered wellness programs for some time. While large employers reportedly see value in promoting wellness, many smaller employers view wellness programs as “window dressing,” according to a broker. One respondent noted that community rating reduced small employers’ interest because their premiums remain the same regardless of efforts to improve employee health.

However, respondents noted that SeeChange health plan is making inroads into the Denver market by marketing wellness programs specifically to small groups. The plan had about 3,000 enrollees in Colorado in 2012 but reportedly is growing quickly, primarily focusing on the Denver, Boulder and Colorado Springs areas. Members who complete a series of recommended activities, including visiting their physician and completing a biometric screening and a health risk assessment, receive lower premiums and cost sharing. Subsequent incentives are based on members’ progress toward specific medical goals.

Creating Limited-Physician Networks

![]() nother way Denver health plans are responding to “unsustainable” cost increases, as described by a health plan respondent, is by building limited-physician networks. These products either limit the physician network outright or tier physicians based on cost and quality measures with enrollees paying more out of pocket if their physician is in a less-preferred tier. One health plan respondent described the development of these products as “an acknowledgement that we can’t keep raising the deductible.”

nother way Denver health plans are responding to “unsustainable” cost increases, as described by a health plan respondent, is by building limited-physician networks. These products either limit the physician network outright or tier physicians based on cost and quality measures with enrollees paying more out of pocket if their physician is in a less-preferred tier. One health plan respondent described the development of these products as “an acknowledgement that we can’t keep raising the deductible.”

Some plans are offering employers a menu of physician networks that vary in restrictiveness. As another respondent said, “It’s really starting to trend toward more network management tools with carriers beginning to offer very similar-looking plan designs with a choice of networks underneath.” One health plan reportedly is offering “double-digit” premium discounts for a narrow-network product. However, a benefits consultant and a respondent from a competing health plan described the premium difference between these products and more conventional products as much lower—3 percent or less.

Anthem offers a narrow-network product—Blue Priority—while United offers a product—Navigate—with narrow-network and tiered-physician options. Anthem’s product reportedly has about a half dozen medical groups currently, but an estimated 15 percent to 20 percent of Anthem’s physician network ultimately might be eligible based on practice attributes and performance on quality measures. In some cases, health plans offer physicians financial incentives for meeting quality goals and reducing use of hospital and other costly services. However, these efforts do not yet have a clear track record of generating savings, and one respondent described employers’ skepticism as linked to the failure of previous efforts to identify and reward high-quality providers to slow cost increases. “Employers have become jaded” toward quality-improvement programs, another respondent said.

The limited-network products are relatively new, and interest and take up has been rather limited to date. Health plan executives were generally confident about growth of limited-network products as an option alongside products with broader networks, predicting that some employers would become cost conscious to the point of offering only limited-network products. Still, as hospitals gain more control over physicians through acquisitions and affiliations, plans’ ability to limit physician networks may diminish.

In contrast to some limited-physician networks, hospital networks remain quite broad and similar across carriers. Plans face difficulty creating products with limited-hospital networks because “the Denver hospitals are virtually all in systems that will not agree to separately contract by hospital,” as one benefits consultant explained. “There’s a bit of a stalemate when it comes to network strategies because of the leverage maintained by the hospital systems,” another said. Respondents indicated that carriers avoid negotiating standoffs with hospitals, particularly in the wake of a 2006 impasse between United and HCA hospitals that temporarily limited United members’ access to Denver-area HCA hospitals.11

However, Kaiser’s growth may make hospitals more amendable to narrow-network products. Kaiser does not operate its own hospitals and contracts with fewer hospitals—primarily Exempla—than most plans. As Kaiser grows, hospitals that don’t contract with Kaiser could lose patients if they become insured by Kaiser and instead use Kaiser-contracted hospitals. One health plan respondent reported that, after Kaiser started serving northern Colorado, non-Kaiser hospitals in that area became willing to negotiate on narrow-network products to gain patient volume.

Medicaid Managed Care Renaissance?

![]() olorado previously had a significant level of risk-based Medicaid managed care. About a decade ago, however, participating health plans filed lawsuits alleging that the state provided inadequate capitated Medicaid payments, which resulted in the state paying back plans and a significant downsizing of risk-based managed care.12 Instead, the state turned to primary care case management (PCCM) arrangements, where the state pays primary care physicians a monthly fee to coordinate care for Medicaid enrollees in addition to regular fee-for-service payments.

olorado previously had a significant level of risk-based Medicaid managed care. About a decade ago, however, participating health plans filed lawsuits alleging that the state provided inadequate capitated Medicaid payments, which resulted in the state paying back plans and a significant downsizing of risk-based managed care.12 Instead, the state turned to primary care case management (PCCM) arrangements, where the state pays primary care physicians a monthly fee to coordinate care for Medicaid enrollees in addition to regular fee-for-service payments.

Today, Denver Health Medicaid Choice—part of Denver Health, the county’s safety net system—is the only Medicaid health plan accepting risk in the Denver area. Limited to the central urban core of the Denver market—Adams, Arapahoe, Denver and Jefferson counties—the plan is growing and currently enrolls about 50,000 people, or almost 20 percent of the market’s Medicaid enrollees. Denver Health’s vertically integrated system—comprised of the county hospital, community health centers, the health plan and the county health department—and availability of information technology and robust patient data by virtue of being an integrated system reportedly help manage care and overall costs. Meanwhile, the Child Health Plan Plus population remains in risk-based plans, with Colorado Access, Kaiser and Denver Health serving the Denver area.

The state is trying to revive risk-based Medicaid managed care through a statewide Accountable Care Collaborative model that will hold new entities responsible for the care and costs of a defined group of Medicaid enrollees. Respondents considered this a managed care “renaissance,” noting the state is working more collaboratively with health plans and providers. The state is emphasizing data collection to help demonstrate improved patient outcomes and efficiency, with a focus on three main goals: reducing emergency department use, high-cost imaging use and hospital readmissions.

To implement the Accountable Care Collaborative, the state created seven regions and, through competitive bidding, contracted with an entity to serve each region in 2011. Five so-called Regional Care Collaborative Organizations were selected—one RCCO serves three regions. RCCOs are owned by providers and/or health plans and help link Medicaid enrollees to health care and social services and coordinate overall care.

Three RCCOs serve the Denver market: the provider-owned Colorado Access health plan and two provider-owned organizations established solely to be RCCOs: Integrated Community Health Partnerships and Colorado Community Health Alliance. Denver RCCOs work primarily with the main safety net providers—with federally qualified health centers and private-practice physicians serving as core primary care providers (medical homes) and Denver Health and Children’s Hospital Colorado as the main hospital providers.

The RCCOs have gradually added patients, with total enrollment of approximately 290,000 statewide by April 2013, or more than 40 percent of the Medicaid population.13 Along with the broader Medicaid population, the RCCOs are focused on serving childless adults newly eligible for Medicaid, who respondents reported are a good fit because they are very low income, previously uninsured and likely need significant care coordination. Enrollment in RCCOs is technically voluntary so individuals can opt out; however, one respondent said that enrollees don’t really know they’re part of a RCCO. Each RCCO enrollee chooses or is assigned to a primary care provider as a medical home but is free to see other Medicaid providers.

Indeed, the more-structured approach to coordinating care appears to be the main way the RCCOs differ from the existing PCCM model. RCCOs receive a per-member, per-month payment to support the provider network and care coordination activities. For instance, RCCO staff helps connect Medicaid patients to providers and facilitates communication among them, assists with care transitions from one setting to another, and identifies social and other services in the community. Additionally, RCCOs and the medical homes are eligible to receive incentive payments for achieving improvements in the three outcome areas.

A state evaluation estimated that the Accountable Care Collaborative saved the state between $9 million and $30 million in FY 2011-2012. This was based on RCCO enrollees experiencing a greater reduction in hospital readmissions and high-cost imaging services than Medicaid enrollees outside of RCCOs. While emergency department utilization increased slightly for both groups, the increase for RCCO enrollees was smaller.14

Providers are still paid fee for service, but RCCOs can submit proposals to pilot new payment methods, with global risk reportedly the ultimate goal. Indeed, the RCCOs’ current contracts end in 2015, at which point respondents expect the state will require RCCOs to bear risk. This may pose a barrier for the two provider-owned RCCOs in Denver that are not licensed health plans. Also, competition may increase because respondents predicted Kaiser and Denver Health will form RCCOs.

Reform Preparations and Expectations

![]() hile Colorado is relatively well prepared to launch key provisions of national health reform, some Denver respondents noted concerns about the state insurance exchange being ready for open enrollment by October 2013. The exchange will be funded in part by a tax on plans sold in the exchange, with additional funding for the exchange currently under discussion. Colorado’s exchange will use a clearinghouse model, meaning any carrier meeting minimum federal requirements can participate. By comparison, six of the 17 state-operated exchanges have chosen the active purchaser model, meaning they will select plans to participate in the exchanges.15

hile Colorado is relatively well prepared to launch key provisions of national health reform, some Denver respondents noted concerns about the state insurance exchange being ready for open enrollment by October 2013. The exchange will be funded in part by a tax on plans sold in the exchange, with additional funding for the exchange currently under discussion. Colorado’s exchange will use a clearinghouse model, meaning any carrier meeting minimum federal requirements can participate. By comparison, six of the 17 state-operated exchanges have chosen the active purchaser model, meaning they will select plans to participate in the exchanges.15

Respondents expected most of the major Denver carriers—Anthem, United and Kaiser—to participate in the exchange. Respondents from one major health plan believed Kaiser may have a competitive advantage in the exchange because of the ACA’s lower excise tax requirements for nonprofit carriers.16 Further, the Colorado Health Insurance Cooperative, a nonprofit, consumer-governed plan established by the Rocky Mountain Farmers Union Educational and Charitable Foundation with ACA funding, plans to sell products inside and outside the exchange through brokers.

Still, as in other markets, health plan executives in Denver voiced a great deal of uncertainty about setting premiums that are high enough to cover their costs and comply with annual state rate review but not too high to lose young, healthy members or require rebates to members if they don’t meet the minimum medical loss ratio. Across the country, there are likely to be similar questions and concerns about setting premiums for products offered in the exchanges, including:

- Risk pools—how sick will the newly insured be compared to the already insured? Will young and healthy enrollees drop out because of higher rates and instead pay the penalty? Which small groups will drop coverage or become self-insured, and how will this affect the risk pool?

- Pent-up demand—will the newly insured make up for months and years of forgone care by using large amounts of medical care?

- Expanded benefits—how much utilization will occur, and how much will premiums increase because ACA minimums exceed benefits of many existing plans, especially in the nongroup market?

- Risk adjustment—how will the health status of enrollees be measured, and how will funds be redistributed among carriers? Will this process adequately account for differences in risk profiles of plan members?

Along with these broader concerns, there are some ways these issues could play out more specifically in the Denver market.

Affordability concerns. In Denver, as elsewhere, respondents expected that nongroup and small-group premiums could increase significantly for many people when the market complies with the ACA’s essential health benefits requirements, cost-sharing limits and modified community rating rules. Although Colorado insurers already are prohibited from adjusting small-group premiums based on health status, the state will need to adopt the ACA’s 3:1 age rating ratio for small-group and nongroup coverage, reducing the degree to which older people can be charged more for coverage than younger people but driving up rates for the young. While respondents expected that subsidies for people with incomes below 400 percent of poverty will help many afford nongroup coverage, they were still concerned that premiums could increase for others. Some Denver respondents expected many young, healthy individuals to forgo coverage and pay the penalty because of “premium shock” as carriers guarantee issue and stop varying premiums by health status. Adverse selection issues in the individual exchange might be compounded by Colorado’s decision to roll high-risk pool members into the exchange.

Respondents also expected premiums to increase in the small-group market as small-group carriers may have to increase benefits and reduce cost sharing to a larger degree than carriers in many other communities. The state selected a small-group plan for its essential health benefits package because other options—the Federal Employee Health Benefits Program, a state employee plan or the largest commercial health maintenance organization in the state—offer more comprehensive benefits and could lead to greater premium increases if selected as the benchmark.17 Still, respondents noted that small-group plans often have individual deductibles of $3,000 or more, while the ACA requires that individual deductibles not exceed $2,000.

Further, several respondents predicted that employer interest in the small-group exchange would trail interest in the nongroup exchange. One health plan respondent expected few small businesses to qualify for new tax credits under the ACA—for employers with up to 25 employees, average annual wages less than $50,000 a worker, and who pay for at least 50 percent of the exchange product premium. Also, respondents expected more small employers to self-insure to avoid new requirements and some small employers to move to a defined-contribution model where they stop offering workers coverage and instead give workers a fixed amount to purchase their own coverage in the nongroup exchange.

Mixed views on the excise tax on expensive health plans. In 2018, the so-called Cadillac tax on health benefits costing more than $10,200 for single coverage and $27,500 for family coverage annually takes effect. Some respondents believed many large employers might try to cut costs to avoid the tax through greater adoption of narrow-network or high-deductible products. “Cost [concerns] with the Cadillac tax will give employers political cover when they need to make changes they haven’t been able to do in the past,” predicted one benefits consultant. “They [employers] can say, ‘The government made me do it or health reform made me do it.’” The tax is of particular concern to public entities that, with relatively rich benefit levels, expect to be hit hard. However, some respondents said large private employers are delaying responses to the Cadillac tax because they ultimately expect the excise tax to be altered or eliminated.

Brokers optimistic. Despite the ACA goal of creating insurance exchanges that facilitate small employers’ and consumers’ ability to buy insurance on their own, brokers expressed confidence that they would continue to play a valuable role in helping businesses select products. As one broker explained, “The professional brokers really are there to provide a service. People think of us as a sales arm, but we spend most of our day advocating between the insurer and employer…. We bring to our clients an understanding of what the market looks like…. If you are going to have an exchange, you will still need somebody to get involved. That’s our role.” Given brokers’ limited role now in the nongroup market, it’s unclear whether brokers will apply to become official navigators for the state exchange. Some brokers had mixed views on whether they or Medicaid outreach organizations alone have the full set of skills in both public and private insurance to help people apply for either type of coverage.

Facilitating enrollment and preparing for churn. According to some respondents, attention and funding are needed to enhance outreach and enrollment for the many people already eligible for Medicaid but not enrolled, plus the many people who will become eligible for either Medicaid or private subsidized coverage. Respondents were concerned about on-time implementation of the Web-based exchange enrollment portal and the information technology infrastructure to determine eligibility for Medicaid and private premium subsidies alike. Particular challenges include existing problems with the state’s eligibility system as well as coordinating Medicaid enrollment processes that vary among the state’s 64 counties. As one Medicaid plan respondent summarized, “We would like it to be the case that clients could enter their information into one integrated system and could have continuous coverage …whether their kids are in Child Health Plan Plus, and they’re on Medicaid, or they’re purchasing a subsidized product on the exchange.”

Churn—the movement of individuals between Medicaid and subsidized private coverage because of income fluctuations—is a concern across markets. But, churn could be especially disruptive in Colorado because of the RCCOs, which are solely focused on Medicaid enrollees and whose networks are largely comprised of safety net providers. According to a market observer, many Medicaid enrollees may have to change providers if they switch to subsidized private coverage or vice versa. Care disruption could be reduced to the degree that commercial and Medicaid plans participate in both markets. Indeed, respondents indicated growing integration between Medicaid and commercial markets, noting that Colorado Access is planning to offer coverage through the exchange, and Kaiser is working to expand its presence in the Medicaid market.

Issues to Track

![]() s health reform unfolds in the coming years, there will be ongoing issues to track in the Baltimore-area health care market, including:

s health reform unfolds in the coming years, there will be ongoing issues to track in the Baltimore-area health care market, including:

- To what extent will Colorado’s early preparations for reform pay off in terms of meeting deadlines and enrolling people in private or Medicaid coverage? To what extent will commercial plans, Medicaid plans and RCCOs participate in the exchange?

- Given the relatively lean benefits in this market, will changes to meet reform requirements contribute to premium rate shock, reducing affordability and discouraging young, healthy people from gaining coverage?

- Will health plans or hospitals be more successful at aligning with physicians and with what effect on overall negotiating leverage between plans and hospitals?

- Will limited-provider networks prove to be the main focus of employers and health plans in the Denver area to curb costs? Will other innovative payment arrangements, such as ACOs, emerge in the market?

- Will the RCCOs prove more successful than Colorado’s past managed care strategies in improving access and quality while controlling the cost of care for Medicaid enrollees?

- What role will brokers play in helping small employers buy insurance? Will brokers increase their presence in the nongroup market by functioning as navigators in the state insurance exchange?

Notes

| 1. | “What’s the Matter with Colorado?” The Economist (March 31, 2011). |

| 2. | U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2010. |

| 3. | Gallup Wellbeing, “Coloradans Least Obese, West Virginians Most for Third Year,” News Release (March 6, 2013). |

| 4. | The Piton Foundation, As Hispanic Population Grows, Metro Counties Look More Like Denver, Denver, Colo. (June 2011). |

| 5. | Piton (2011). |

| 6. | U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages, 2011, http://www.bls.gov/cew/ew11table4.pdf (accessed May 17, 2013). |

| 7. | Colorado Legislative Council Staff, “Mandated Health Insurance Benefits,” Memorandum (July 1, 2011). Colorado’s mental health parity mandate only applies to groups with more than 50 employees. |

| 8. | Colorado’s 1992 Taxpayer Bill of Rights (TABOR) amendment restricts revenue growth at the state and local level, requiring voter approval to raise tax rates or spend revenues collected under existing tax rates if revenues grow faster than the rate of inflation and population growth. Without voter approval, any surplus revenues are returned to taxpayers. |

| 9. | Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Medicaid Enrollment: December 2009 Data Snapshot, Washington, D.C. (September 2010). |

| 10. | Lockton Companies, 2013 Colorado Employer Benefits Survey Report, Denver, Colo. (Oct. 26, 2012). |

| 11. | Shanley, Will, “HCA, UnitedHealthcare Mend Relationship,” The Denver Post (Nov. 4, 2006). |

| 12. | Hill, Ian, State Responses to Budget Crises in 2004: Colorado, The Urban Institute, Washington, D.C. (February 2004). |

| 13. | Colorado Department of Health Care Policy and Financing, At a Glance, Denver, Colo. (April 30, 2013). |

| 14. | Colorado Department of Health Care Policy and Financing, Accountable Care Collaborative Annual Report, Denver, Colo. (Nov. 1, 2012). |

| 15. | Kaiser Family Foundation, State Decisions for Creating Health Insurance Exchanges, as of May 10, 2013, http://www.statehealthfacts.org/comparemaptable.jsp?ind=962&cat=17 (accessed May 17, 2013). |

| 16. | Beginning in 2014, the ACA requires insurers to pay an annual fee based on their market share (their net premium revenues as a share of total net premium revenue). Nonprofit insurers are only required to pay taxes on half of their net premium revenues. |

| 17. | Colorado Department of Regulatory Agencies, Division of Insurance, Draft Recommendations for EHB Benchmark Plan, Denver, Colo. (Aug. 31, 2012). |

Data Source

As part of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s (RWJF) State Health Reform Assistance Network initiative, the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC) examined commercial and Medicaid health insurance markets in eight U.S. metropolitan areas: Baltimore; Portland, Ore.; Denver; Long Island, N.Y.; Minneapolis/St. Paul; Birmingham, Ala.; Richmond, Va.; and Albuquerque, N.M. The study examined both how these markets function currently and are changing over time, especially in preparation for national health reform as outlined under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010. In particular, the study included a focus on the impact of state regulation on insurance markets, commercial health plans’ market positions and product designs, factors contributing to employers’ and other purchasers’ decisions about health insurance, and Medicaid/state Childrens’ Health Insurance Program (CHIP) outreach/enrollment strategies and managed care. The study also provides early insights on the impact of new insurance regulations, plan participation in health insurance exchanges, and potential changes in the types, levels and costs of insurance coverage.

This primarily qualitative study consisted of interviews with commercial health plan executives, brokers and benefits consultants, Medicaid health plan executives, Medicaid/CHIP outreach organizations, and other respondents—for example, academics and consultants—with a vantage perspective of the commercial or Medicaid market. Researchers conducted 17 interviews in the Denver market between November 2012 and March 2013. Additionally, the study incorporated quantitative data to illustrate how the Denver market compares to the other study markets and the nation. In addition to a Community Report on each of the eight markets, key findings from the eight sites will also be analyzed in two publications, one on commercial insurance markets and the other on Medicaid managed care.