Competitive Albuquerque Health Insurance Market Gears Up for Coverage Boom

RWJF Reform Community Report

October 2013

Chapin White, Laurie E. Felland, Ellyn R. Boukus, Kevin Draper

![]() ith pragmatism prevailing in New Mexico’s political tug of war over national health reform, Albuquerque health insurers are eager to compete for new Medicaid enrollees and people eligible for subsidized private health coverage, according to a new Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC) study of the region’s commercial and Medicaid insurance markets (see Data Source). While partisan differences and turf battles initially delayed implementation of key provisions of the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), state leaders have established a state insurance exchange and agreed to expand Medicaid to people with incomes below 138 percent of poverty as of January 2014. As a result, new carriers are entering the commercial health insurance market to offer products on the exchange, and Medicaid managed care plans are gearing up for a major state overhaul of the program that will coincide with an estimated 150,000 or more people gaining Medicaid coverage statewide.

ith pragmatism prevailing in New Mexico’s political tug of war over national health reform, Albuquerque health insurers are eager to compete for new Medicaid enrollees and people eligible for subsidized private health coverage, according to a new Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC) study of the region’s commercial and Medicaid insurance markets (see Data Source). While partisan differences and turf battles initially delayed implementation of key provisions of the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), state leaders have established a state insurance exchange and agreed to expand Medicaid to people with incomes below 138 percent of poverty as of January 2014. As a result, new carriers are entering the commercial health insurance market to offer products on the exchange, and Medicaid managed care plans are gearing up for a major state overhaul of the program that will coincide with an estimated 150,000 or more people gaining Medicaid coverage statewide.

Compared to many communities, Albuquerque has a relatively competitive health care market, which may contribute to a smoother transition under health reform. For example, two of the three major health plans are part of local integrated delivery systems that compete vigorously on costs and reputation. Also, the Medicaid program is unusually well integrated into the overall Albuquerque insurance market and delivery system, with many of the same plans and providers serving both Medicaid and commercial enrollees. Still, the ACA will require tightening of regulations in the nongroup, or individual, and small-group insurance markets. Key factors likely to influence how reform plays out in Albuquerque include:

- Many low-income residents. Albuquerque is home to many low-income people and workers in small firms who face challenges gaining health insurance. As a result, the ACA will likely produce dramatic coverage gains, as Medicaid eligibility expands and new federal subsidies become available for lower-to-middle-income people to buy private coverage in new state health insurance exchanges.

- Three competing hospital systems. Albuquerque hospital systems—Presbyterian Healthcare Services, Lovelace Health System and the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center—compete in similar geographic service areas. Many physicians are aligned through employment or other means with a particular hospital system.

- Local health plan competition. Three insurance carriers—Blue Cross Blue Shield of New Mexico (BCBSNM), along with two provider-owned plans, Presbyterian Health Plan and Lovelace Health Plan—compete vigorously with national insurers like UnitedHealth Group in the nongroup and small-group markets.

- Limited networks accepted. Unlike many markets that have moved away from health maintenance organization (HMO) products that limit patients’ choice of providers, HMOs are common in Albuquerque. Meanwhile, demand for high-deductible health plans, which offer lower premiums in exchange for higher out-of-pocket cost sharing, is relatively low.

- Overhauled and expanded Medicaid program. Under a federal demonstration waiver, New Mexico is streamlining Medicaid managed care—which will be known as Centennial Care—by reducing the number of plans, integrating physical, behavioral and long-term care services that have been managed in a more piecemeal way, and steering patients to primary care. At the same time, Medicaid coverage will become available to tens of thousands of low-income people.

- Competitive state insurance exchange. The three major local insurers are offering exchange products, and two new entrants to the commercial market—Molina Healthcare and New Mexico Health Connections, a co-op plan—are selling products in the exchange. BCBSNM has developed a low-premium, narrow-network product for the exchange, and other carriers are developing similar products.

Table of Contents

Market Background

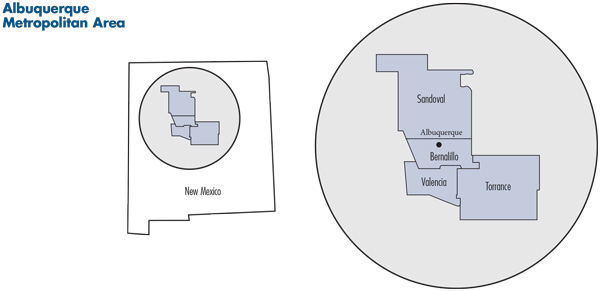

![]() ith about 900,000 residents, the Albuquerque metropolitan area is relatively small compared to other metro areas, but the four-county region—Bernalillo, Sandoval, Torrance and Valencia—is home to almost half of New Mexico’s residents (see map). The region is among the fastest growing areas in the country, with the population increasing by 22 percent over 10 years, more than double the national metropolitan average (see Table 1). New Mexico is one of a growing number of so-called majority-minority states—Latinos account for almost half of the Albuquerque population and almost 70 percent of population growth since 2000. Whites and blacks make up 42 percent and slightly more than 2 percent, respectively, of the population. The area has a strong pre-Columbian history and identity, and Native Americans, at about 6 percent of the population, constitute a relatively large share of residents.

ith about 900,000 residents, the Albuquerque metropolitan area is relatively small compared to other metro areas, but the four-county region—Bernalillo, Sandoval, Torrance and Valencia—is home to almost half of New Mexico’s residents (see map). The region is among the fastest growing areas in the country, with the population increasing by 22 percent over 10 years, more than double the national metropolitan average (see Table 1). New Mexico is one of a growing number of so-called majority-minority states—Latinos account for almost half of the Albuquerque population and almost 70 percent of population growth since 2000. Whites and blacks make up 42 percent and slightly more than 2 percent, respectively, of the population. The area has a strong pre-Columbian history and identity, and Native Americans, at about 6 percent of the population, constitute a relatively large share of residents.

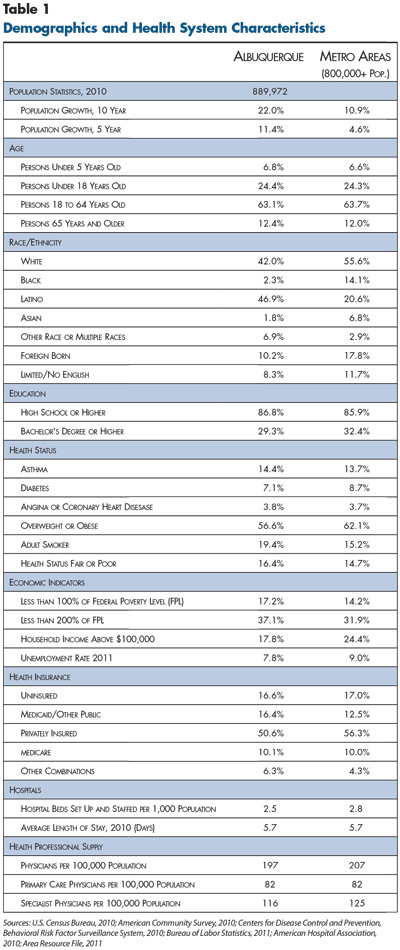

Albuquerque-area residents tend to have lower incomes, with 37 percent of the population having incomes below 200 percent of poverty compared to the metropolitan average of about 32 percent. The proportion of Albuquerque residents without health insurance (16.6%) tracks the metropolitan average, but the region has a relatively low level of private health coverage—about 50.6 percent compared to the metropolitan average of 56.3 percent. The area also tends to have more small employers, which are less likely to offer health coverage. In New Mexico, half of workers are in firms with fewer than 50 employees, compared to 45 percent for states on average.1 Albuquerque residents on average have lower levels of diabetes and obesity than metropolitan areas overall but higher prevalence of asthma, smoking and fair or poor health status.

A bright spot in Albuquerque’s economy is a relatively low unemployment rate, which was below the metropolitan average during and after the Great Recession of 2007-09. Along with many small firms, the region is home to large federal government institutions, including Sandia National Laboratories and Kirtland Air Force Base, and associated private contractors. Other large employers include Intel, the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque Public Schools and the three major hospital systems.

State Regulatory Approach

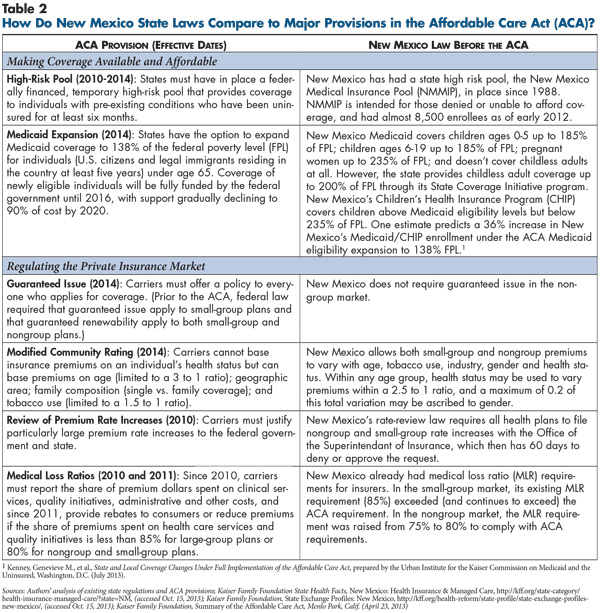

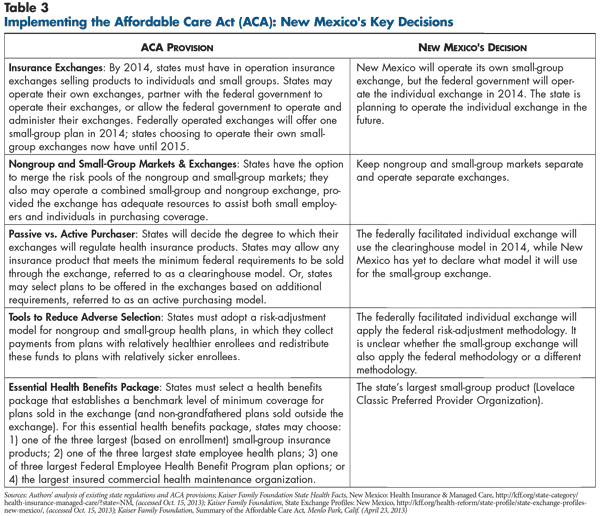

![]() ew Mexico historically has imposed few rating restrictions on insurance carriers. The state currently allows nongroup carriers to deny individuals coverage and allows nongroup and small-group carriers to rate premiums by age, tobacco use, industry, gender and health status, albeit with some restrictions on the last two factors (see Table 2).2 To meet ACA requirements, New Mexico will start requiring nongroup plans to offer coverage to all (subject to capacity) and vary nongroup and small-group premiums only by age and tobacco use (see Table 3). Just before passage of the ACA, New Mexico implemented a medical loss ratio requirement of 85 percent for small-group products—more stringent than the ACA’s 80 percent—and 75 percent in the nongroup market, which has since been raised to 80 percent to comply with the ACA. In 2011, New Mexico enacted a measure to allow the superintendent of insurance to review insurers’ overall financial health and improve transparency of the rate-review process.

ew Mexico historically has imposed few rating restrictions on insurance carriers. The state currently allows nongroup carriers to deny individuals coverage and allows nongroup and small-group carriers to rate premiums by age, tobacco use, industry, gender and health status, albeit with some restrictions on the last two factors (see Table 2).2 To meet ACA requirements, New Mexico will start requiring nongroup plans to offer coverage to all (subject to capacity) and vary nongroup and small-group premiums only by age and tobacco use (see Table 3). Just before passage of the ACA, New Mexico implemented a medical loss ratio requirement of 85 percent for small-group products—more stringent than the ACA’s 80 percent—and 75 percent in the nongroup market, which has since been raised to 80 percent to comply with the ACA. In 2011, New Mexico enacted a measure to allow the superintendent of insurance to review insurers’ overall financial health and improve transparency of the rate-review process.

Before the ACA’s passage, New Mexico also had implemented measures to help people gain private coverage. The New Mexico Health Insurance Alliance is a quasi-public alliance of health insurers created by the state Legislature in 1994 to sell coverage to small businesses, the self-employed, and individuals who lost group coverage and exhausted any continuation coverage. Funded by premiums and carrier assessments, the alliance offers a comprehensive coverage product through the major carriers. Unlike the nongroup market, the alliance offers coverage without medical underwriting, and, unlike the small-group market, it offers group coverage to the self-employed. Still, alliance enrollment has been relatively low—less than 4,300 in 2012—reportedly because of high premiums. The state initially envisioned that the alliance would serve as an insurance exchange—similar to the state exchanges under the ACA—although the alliance lacked the federal subsidies that the ACA will provide.

The state has operated a high-risk pool, the New Mexico Medical Insurance Pool (NMMIP), since 1988 for people denied coverage because of pre-existing conditions or charged a premium more than 125 percent of the standard rate. The NMMIP is administered by Blue Cross Blue Shield of New Mexico and had approximately 8,500 enrollees in 2012. The state folded an ACA-required federal high-risk pool into NMMIP, but enrollment in the federal high-risk pool was suspended in March 2013 because of dwindling federal funding.3

Large Medicaid Program

![]() ew Mexico covers many low-income people through Medicaid and the state Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). The state is unusual in combining relatively expansive eligibility with relatively high provider payment rates—often states have one or the other. About 525,000 people were enrolled in New Mexico’s Medicaid/CHIP program in April 2013—more than a quarter of the state’s population and the fifth highest rate in the nation. Medicaid income-eligibility cutoffs for pregnant women and children 18 and younger are higher than in most states, at up to 235 percent of poverty for pregnant women and 185 percent for children, with CHIP covering children from 186 percent to 235 percent of poverty. Low-income parents can receive coverage: if working, up to 85 percent of poverty, if not working, up to 28 percent of poverty.

ew Mexico covers many low-income people through Medicaid and the state Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). The state is unusual in combining relatively expansive eligibility with relatively high provider payment rates—often states have one or the other. About 525,000 people were enrolled in New Mexico’s Medicaid/CHIP program in April 2013—more than a quarter of the state’s population and the fifth highest rate in the nation. Medicaid income-eligibility cutoffs for pregnant women and children 18 and younger are higher than in most states, at up to 235 percent of poverty for pregnant women and 185 percent for children, with CHIP covering children from 186 percent to 235 percent of poverty. Low-income parents can receive coverage: if working, up to 85 percent of poverty, if not working, up to 28 percent of poverty.

Nondisabled, childless adults are not currently eligible for Medicaid, but workers who earn up to 200 percent of poverty may receive coverage through the State Coverage Insurance (SCI) program, a Medicaid demonstration waiver. The SCI is offered to individuals or through employers and funded through a blend of individual and employer contributions, along with state and federal funds. This program offers limited benefits, charges modest premiums and includes sliding-scale cost sharing for services. The state has limited enrollment to 40,000 people since November 2009 because of an enrollment cap in the SCI waiver agreement.

Unrelated to the ACA, New Mexico has streamlined the Medicaid application process and conducted outreach activities to encourage enrollment, which also are expected help enroll additional people under reform. Children and pregnant women can gain immediate access to the program through presumptive eligibility, which offers short-term coverage for up to 60 days while formal applications are processed. The state also places workers at hospitals and health services organizations to screen and enroll Medicaid applicants on site. Starting in late-2013, the state is also rolling out a streamlined online application system.

Still, from an administrative perspective, New Mexico’s Medicaid program is complex and fragmented. The state deems people eligible for the program if they fall in one of approximately 40 different eligibility categories and manages services for enrollees through 12 federal waivers. Respondents expect less fragmentation as the state expands Medicaid under the ACA and streamlines the program under Centennial Care.

Three Competing Hospital Systems

![]() hree hospital systems serve Albuquerque: Presbyterian Healthcare Services, with three acute-care hospitals and a total of more than 700 beds; Lovelace Health System with four acute-care hospitals and 500 total beds; and the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center (UNM) with two acute-care hospitals and approximately 600 beds.4

hree hospital systems serve Albuquerque: Presbyterian Healthcare Services, with three acute-care hospitals and a total of more than 700 beds; Lovelace Health System with four acute-care hospitals and 500 total beds; and the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center (UNM) with two acute-care hospitals and approximately 600 beds.4

The hospital systems’ service areas overlap heavily—all three campuses are clustered downtown within a mile of each other, and all three systems have built facilities in the fast-growing areas west of the Rio Grande. As a teaching facility with the only Level 1 trauma center in the state, UNM provides a large safety net role for low-income patients, as well as specialized care that the other systems don’t offer, giving UNM broad appeal as a so-called must-have provider in health plan networks. UNM also offers a program that coordinates and heavily subsidizes care for about 30,000 low-income, uninsured Albuquerque residents. Most Albuquerque physicians are employed, either in one of the hospital system’s medical groups or in large independent practices.

Uninsured people and Medicaid enrollees in Albuquerque primarily receive care through the three health systems, several federally qualified health centers, other safety net clinics and some private-practice physicians. Given the relatively high proportion of Native Americans in the area, the Indian Health Service is also an important part of the Albuquerque safety net (see box below). Respondents indicated that relatively high Medicaid enrollment, coupled with relatively low rates of commercial coverage, leads most providers to accept Medicaid patients. New Mexico’s relatively high Medicaid payment levels, with rates almost on par with Medicare payment, also reportedly encourage provider participation.

Albuquerque’s per capita supply of hospital beds and physicians is similar to that of other metropolitan areas. Still, access to care can be challenging in the more rural areas of the market, which suffer from sparse provider supply and long travel distances to provider facilities. Further, respondents noted considerable concern that provider capacity will be insufficient throughout the market as many people potentially gain insurance coverage and seek health care services under health reform. One respondent noted that the state Legislature may consider expanding physician assistants’ scope of practice as one way to address shortages of primary care providers.

Access to Care for Native Americans To accommodate particular barriers to care and the rural nature of many Native American communities, the safety net for Native American pueblos, tribes and nations is broader than the traditional safety net. The federal Indian Health Service provides health care to Native Americans by operating outpatient facilities and is the payer of last resort for services received in other facilities. Low-income Native Americans also are eligible for Medicaid and have the option of choosing a Medicaid health plan but are not required to be in managed care except for those receiving long-term care services or dually eligible for Medicaid and Medicare. A state proposal to mandate enrollment in managed care for Native Americans in Centennial Care, the state’s revamped Medicaid program, was disallowed by the federal government, although Native Americans have the option to enroll. Also, new cost-sharing requirements under Centennial Care—including copayments for non-urgent emergency department use—do not apply to Native Americans because of federal requirements. The ACA also includes special provisions for Native Americans—they are exempt from the individual mandate penalties, they will not face any cost sharing if they enroll in an exchange plan and have income below 300 percent of poverty, and they may enroll in exchange plans at any time, not just during an annual open-enrollment period. |

Competitive Health Insurance Market

![]() n contrast to the increasingly consolidated commercial health insurance market in many metropolitan areas, the Albuquerque market remains relatively competitive. The region has long been served by three major plans: BCBSNM, a part of Health Care Service Corp., a mutual company that operates Blue plans in four other states; Presbyterian Health Plan, owned by nonprofit Presbyterian Healthcare Services;5 and Lovelace Health Plan, which is owned by Nashville, Tenn.-based Ardent Health Services, a for-profit hospital chain that also owns Lovelace Health System.

n contrast to the increasingly consolidated commercial health insurance market in many metropolitan areas, the Albuquerque market remains relatively competitive. The region has long been served by three major plans: BCBSNM, a part of Health Care Service Corp., a mutual company that operates Blue plans in four other states; Presbyterian Health Plan, owned by nonprofit Presbyterian Healthcare Services;5 and Lovelace Health Plan, which is owned by Nashville, Tenn.-based Ardent Health Services, a for-profit hospital chain that also owns Lovelace Health System.

Although BCBSNM is the largest carrier in the state, the commercial insurance market in Albuquerque is fairly competitive across group size. Statewide, BCBSNM has about half of the nongroup sector, while Presbyterian has about a third of the market. BCBSNM, Presbyterian and Lovelace each hold roughly 30 percent of the small-group market. National carriers UnitedHealth Group and Cigna are also in the commercial market and account for the remainder of nongroup and small-group enrollment. In the large-group market, BCBSNM has about 40 percent of the market statewide, followed by Presbyterian with 29 percent and Lovelace with 24 percent.6

While both the Presbyterian and Lovelace health plans are closely tied to their respective hospital systems, respondents perceived Presbyterian as having stronger local roots and more stability, noting that employers that can afford a higher premium appear to prefer the Presbyterian brand. Lovelace, on the other hand, is viewed as aggressively competing on price for employers’ business. Reportedly Ardent’s acquisition of the Lovelace hospital system and health plan a decade ago undermined Lovelace’s community ties and perception as a local plan, but recent investments in Albuquerque have strengthened the plan’s community ties.

Three recent events also have contributed to speculation about Lovelace Health Plan’s future. First, in late-2012, contract renegotiations broke down between Lovelace and ABQ Health Partners, a large multispecialty physician group that historically was central to the plan’s identity. After an acrimonious public dispute, ABQ Health Partners left the Lovelace network. Second, Lovelace lost significant enrollment after losing a bid to continue serving Medicaid patients and subsequently sold its Medicaid enrollment to Molina Healthcare. And, third, the Lovelace Health Plan CEO abruptly departed in mid-2013, with Optum, a subsidiary of UnitedHealth Group, stepping in to manage the plan until a new CEO is selected.

HMO Tradition Ties Plans to Providers

![]() hile HMOs with modest copayments and low or no deductibles all but disappeared from many markets, they continue to be the most popular product type in Albuquerque, followed by preferred provider organization (PPO) products. High-deductible health plans remain largely absent in Albuquerque. In line with the prevalence of HMOs, Albuquerque is well ahead of the national curve in employer and consumer acceptance of products with limited-provider networks.

hile HMOs with modest copayments and low or no deductibles all but disappeared from many markets, they continue to be the most popular product type in Albuquerque, followed by preferred provider organization (PPO) products. High-deductible health plans remain largely absent in Albuquerque. In line with the prevalence of HMOs, Albuquerque is well ahead of the national curve in employer and consumer acceptance of products with limited-provider networks.

Beyond the universal need to contract with the University of New Mexico flagship hospital, health plans in the market generally limit hospital contracts to either the Lovelace or Presbyterian systems. BCBSNM’s hospital network includes UNM and Lovelace but excludes Presbyterian. Respondents reported that many employers and employees in the market generally accept that choosing a health plan equates to picking a hospital system and physician group.

There appear to be limited provider-payment innovations in the market, with the exception of the Presbyterian Health Plan, which puts affiliated hospitals and physicians at risk for the cost of patients’ care through capitated—fixed, per-member, per-month—payments. Presbyterian Healthcare Services also developed a Medicare Pioneer accountable care organization in late 2011 but dropped out in 2013, citing difficulties achieving savings because service utilization was already low.7 Presbyterian also has accelerated acquisition of physician practices, although respondents perceived only limited administrative and clinical integration of the acquired practices.

Revamping Medicaid Managed Care

![]() ew Mexico has long supported Medicaid managed care. Approximately three-quarters of Medicaid enrollees statewide are enrolled in health plans participating in the state’s risk-based managed care program Salud! Managed care is mandatory for pregnant women, parents, children and disabled individuals, except those who are Native American.

ew Mexico has long supported Medicaid managed care. Approximately three-quarters of Medicaid enrollees statewide are enrolled in health plans participating in the state’s risk-based managed care program Salud! Managed care is mandatory for pregnant women, parents, children and disabled individuals, except those who are Native American.

Historically, all three major commercial carriers in the market have also offered Medicaid managed care products statewide. Presbyterian Health Plan has been the largest Medicaid plan, with almost 45 percent of the state market in early 2013, followed by Lovelace Health Plan with a 21-percent market share and BCBSNM with about 10 percent. Molina Healthcare, a national for-profit carrier that specializes in Medicaid, serves about 23 percent of the market. Three other carriers have historically provided carve-out services to Medicaid patients: UnitedHealthcare Community Plan of New Mexico; Amerigroup, a WellPoint subsidiary, for long-term care; and Optum Health, a United subsidiary, for behavioral and mental health services.

However, plan participation in Medicaid is changing as New Mexico revamps its managed care program for 2014. The state aims to streamline administration of the program—which will be called Centennial Care—with a goal of containing costs and improving patient care. The state is combining 12 federal waivers tied to managing different services into one overall waiver and shifting to a patient-centered medical home model that emphasizes integrating and coordinating services across care settings. The state also required all participating health plans to bid competitively to provide all Medicaid-covered services—medical, behavioral and mental health, home- and community-based services, and long-term care—under fixed per-member, per-month payments, or capitation.

In February 2013, the state selected four plans to participate in Centennial Care for 2014: Presbyterian, BCBSNM, United and Molina. Several factors reportedly strengthened these plans’ bids: Presbyterian is an integrated delivery system and has been the largest plan; Molina specializes in public programs; BCBSNM has strong brand recognition as a commercial plan; and United has experience serving commercial enrollees’ broad health needs and managing long-term care services under the previous waiver. Lovelace lost its Medicaid contract, which represents a major shakeup for the plan and the state’s Medicaid market.

With Lovelace’s contract terminated, Molina recently acquired Lovelace’s Medicaid members, which immediately doubled Molina’s Medicaid enrollment, putting Molina on par with Presbyterian as far as market share. The transfer in enrollment was negotiated between Lovelace and Molina and was approved by the state. Lovelace plan enrollees who have switched to Molina can continue to receive care from Lovelace providers under the new arrangement.

In the coming years, Medicaid managed care enrollment will increase significantly in New Mexico. The ACA Medicaid expansion will extend coverage to almost all residents with incomes under 138 percent of poverty, including nondisabled, childless adults for the first time. And, the individual mandate and exchanges will likely lead many individuals to enroll in Medicaid who otherwise would not. How the enrollment increase, along with United’s expanded role, will affect competition and market shares remains to be seen.

Provider networks reportedly are quite similar across Medicaid health plans, with the exception of the Presbyterian health system that, in the four-county metropolitan area, only serves Medicaid enrollees in the Presbyterian plan.

While Medicaid health plans now pay providers predominantly on a fee-for-service basis, the state wants Medicaid plans to implement new payment arrangements under Centennial Care. Respondents suggested that the state’s more streamlined approach to plan contracting, as well as some health plans’ alignment with providers, could facilitate the development of Medicaid accountable care organizations—groups of providers that are responsible for the cost and quality of care for a defined patient population.

Stop-and-Go Reform

![]() hen the ACA passed in 2010, then-Gov. Bill Richardson (D) embraced reform and forged ahead with plans for a state-run insurance exchange. However, preparations stalled under his successor, Susana Martinez, a Republican who took office in January 2011. She initially vetoed legislation to establish a state-run insurance exchange and delayed a decision until January 2013 to expand Medicaid.

hen the ACA passed in 2010, then-Gov. Bill Richardson (D) embraced reform and forged ahead with plans for a state-run insurance exchange. However, preparations stalled under his successor, Susana Martinez, a Republican who took office in January 2011. She initially vetoed legislation to establish a state-run insurance exchange and delayed a decision until January 2013 to expand Medicaid.

Gov. Martinez proposed establishing the New Mexico exchange administratively by designating the existing New Mexico Health Insurance Alliance (NMHIA) as the state exchange. The state Legislature resisted the approach, however, because NMHIA was led by appointees of the health plans and the governor. Legislators objected to simply designating NMHIA as the exchange without authorizing legislation, presumably because they wanted to be able to appoint some members to the exchange board.

Martinez, after working with the Legislature to find a compromise, signed legislation establishing an exchange in March 2013. The newly created exchange board includes six members appointed by the governor, six by the Legislature, plus the state superintendant of insurance and human services secretary. Although the new exchange is officially distinct from NMHIA, there is some continuity—the chairman of the new exchange board was on the NMHIA board, and the NMHIA executive director was hired as the interim CEO of the exchange.

Time pressures and technological challenges led the state in May 2013 to fall back on a hybrid model for the exchange. The small-group exchange will be state run, while the nongroup exchange will be federally facilitated, but the state will assume responsibility for plan management activities, including approving qualified health plans, regulating premiums and conducting enrollment outreach. At some point, the state intends to shift to a state-run nongroup exchange.

The state selected the largest small-group product, the Lovelace Classic PPO, as the benchmark essential health benefits plan. A number of consumer advocacy organizations and health professionals have criticized the Lovelace PPO for having weak coverage of mental health services.8

Respondents in Albuquerque cited a number of common questions and concerns about setting premiums for products offered in the exchange, similar to those heard in other markets across the country, including:

- Risk pools—How sick will the newly insured be compared to the currently insured? Will young and healthy enrollees drop out because of higher rates and instead pay the tax penalty? Which small groups will drop coverage and how will this affect the risk pool?

- Pent-up demand—will the newly insured make up months and years of forgone care by using large amounts of medical care?

- Expanded benefits—how much utilization will occur, and how much will premiums increase because ACA minimums exceed benefits of many existing plans, especially in the nongroup market?

- Risk adjustment—how will the health status of enrollees be measured, and how will funds be redistributed among carriers? Will this process adequately account for differences in risk profiles of plan members?

Along with these broader concerns, there are some additional ways these issues could play out more specifically in the Albuquerque market.

Broad health plan interest in the exchange. To date, five health plans are offering products for the Albuquerque market on the New Mexico insurance exchange. This group includes the established commercial plans—BCBSNM, Presbyterian and Lovelace—and Molina, a new entrant to the commercial market that previously served only Medicaid and Medicare enrollees. Additionally, a new co-op plan, New Mexico Health Connections (NMHC), is participating in the exchange. Molina offers nongroup products while the other four offer both nongroup and small-group products. According to a plan executive, the co-op will focus on supporting primary care through community health centers and collecting data on costs and patient outcomes. National plans Cigna and United are not offering exchange products in 2014.

Nongroup premiums expected to be relatively affordable. According to the state,9 premiums in 2014 for a silver-level policy for a 40-year-old nonsmoker in Albuquerque will range from $189 to $258 a month, with the second-lowest silver premium of $212 determining the level of federal subsidy an individual receives regardless of the plan chosen. New Mexico’s insurance superintendent had expected premiums in the nongroup and small-group markets for similar products to rise by roughly 10 percent in 2014 but premiums are only about 5 percent higher on average.10 Also, one report indicates Albuquerque’s premiums in 2014 will be lower than in most markets.11

Presbyterian’s proposed rates were the highest among small-group products and roughly average among nongroup products. Proposed premiums from Lovelace are at or below average in both market segments, consistent with its reputation as an aggressive competitor on price. Lovelace’s low premiums also may be a bid to gain enrollment following recent membership declines. As new entrants to the commercial market, Molina and New Mexico Health Connections had to set premiums without the benefit of any claims experience. Both are offering products with competitive premiums, lower than Presbyterian and Lovelace. BCBSNM is offering widely divergent plans. At one end are BCBSNM’s PPO products, which offer a traditional network but with relatively high premiums. At the other end is BCBSNM’s new Blue Community HMO, a narrow-network product offering by far the lowest premium in the exchange—$189 for silver-level individual coverage for a 40-year-old compared to an average premium of $232. Other health plans have not created new products specifically for the exchange.

Employers consider moves to sidestep regulations. As in other markets, Albuquerque respondents discussed ways in which employers may try to avoid ACA requirements. Although respondents reported that employers have been conservative about moving to self-insurance, a few respondents noted heightened interest among increasingly smaller employers, even as small as 25 employees. Currently, Lovelace and Presbyterian health plans will only offer a self-insured option to employers with at least 250 enrollees, though Presbyterian is creating a product targeting employers with as few as 25 employees. And a number of respondents predicted that some employers may choose to drop coverage and employer contributions altogether, shifting employees to the individual exchange, though they typically agreed this would be unlikely until after the first year of exchange operation.

Brokers feel secure. Unlike other markets, respondents did not express much concern about the role of brokers in the exchange environment. According to recommendations from a state task force, brokers will likely continue to assist small employers and individuals buy insurance and help individuals apply for coverage through the exchange or Medicaid.12 Brokers will continue to receive commissions from carriers, rather than from the exchange.13 Still, one respondent pointed out that the new medical loss ratio requirements are pressuring carriers to reduce administrative costs, with United ending broker commissions, leaving brokers to instead bill employers directly for their services.

Medicaid expansion moving forward. New Mexico is one of a growing number of states with Republican governors to opt for the ACA’s Medicaid expansion. With nearly 40 percent of nonelderly adults in the state earning below 138 percent of poverty, one estimate predicts that full implementation of the Medicaid expansion will increase Medicaid/CHIP enrollment in New Mexico by about 35 percent, or more than 150,000 new enrollees.14

Respondents expect robust competition among Medicaid health plans. While BCBSNM is a relatively new entrant to the Medicaid market, many expected the Blue plan to attract many new enrollees by virtue of reputation and brand recognition. Three of the four Centennial Care plans—BCBSNM, Presbyterian and Molina—are selling commercial products on the exchange, positioning them to compete for the subsidized population and minimize coverage disruptions among those whose income fluctuates between Medicaid and subsidized private coverage eligibility. Despite these options, New Mexico is continuing to explore the possibility of establishing a Basic Health Program, which allows states to use federal funds to offer subsidized coverage to adults with incomes between 139 percent and 200 percent of poverty who would otherwise be eligible for premium subsidies on the exchange. However, federal implementation of this program has been delayed until 2015.

With more than 20 percent of New Mexicans currently uninsured, the number of residents expected to gain Medicaid coverage or other insurance under the ACA is expected to be large relative to other states. New Mexico’s uninsurance rate is projected to drop by 16 percentage points under the ACA—the second-largest decline expected among states.15

Issues to Track

- Will efforts succeed to enroll the large uninsured population in Albuquerque in Medicaid or subsidized private coverage on the exchange? Will small employers add to exchange enrollment by dropping coverage in large numbers?

- Will the Lovelace Health Plan overcome recent challenges to remain viable?

- What impact will the state’s overhaul of its Medicaid managed care program, coupled with the Medicaid expansion, have on health plan competition and enrollees’ access to services, provider payment and overall program costs?

- Will the New Mexico Health Connections co-op plan get off the ground in the exchange? How successful will it be in differentiating itself from the existing players?

- In the exchange, will BCBSNM’s new narrow-network HMO be popular?

- Will UnitedHealth Group continue to stay out of the exchange? If so, will its Medicaid plan become less attractive because it cannot hold onto enrollees who “churn” between eligibility for Medicaid and subsidized private coverage?

- Will New Mexico successfully manage the transition to a state-run nongroup exchange, and what implications will that have on plan participation and enrollment?

- How adequate will provider supply be as more people gain coverage and seek services, particularly in rural areas already struggling with provider shortages?

Notes

| 1. | U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages, Table 4, Private Industry by Supersector and Size of Establishment: Establishments and Employment, First Quarter 2011, by State, http://www.bls.gov/cew/ew11table4.pdf (accessed Aug. 23, 2013). |

| 2. | Within any age group, health status may be used to vary premiums within a 250% (2.5:1) rate band. A maximum of 20% of this 250% total variation may be ascribed to gender. |

| 3. | In early 2013, the federal government notified states administering their own temporary high-risk pools of a contract change that would shift more financial responsibility to these states. The new contract would reduce the level of federal funding to states while allowing them to make necessary changes to premiums, benefit design, cost sharing and networks to remain solvent. States not wanting to accept these new terms could instead opt to transition to a federally run Pre-existing Condition Insurance Plan (PCIP). In May 2013, the NMMIP Board voted to accept the new terms and continue running the PCIP program, with supplemental funding from the state and insurers, rather than transition responsibility to the federal government. |

| 4. | HealthLeaders Interstudy, Market Overview: Albuquerque, Nashville, Tenn. (March 2012). |

| 5. | Presbyterian Health Services owns Presbyterian Health Plan and Presbyterian Delivery System, which is made up of eight hospitals statewide and Presbyterian Medical Group. |

| 6. | Kaiser Family Foundation, Large Group Insurance Market Competition, http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/large-group-insurance-market-competition-2011/?state=NM (accessed Sept. 30, 2013). Analysis of data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Center for Consumer Information & Insurance Oversight, Public Use File for 2011, http://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Data-Resources/mlr.html (accessed Sept. 30, 2013). |

| 7. | Evans, Melanie, “Risk Was Too Great,” Modern Healthcare, (July 20, 2013) |

| 8. | The New Mexico Center on Law and Poverty, comment letter concerning New Mexico's benchmark plan selection, http://nmpovertylaw.org/WP-nmclp/wordpress/WP-nmclp/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/Comments-to-CCIIO-Letter-to-Franchini-Change-Benchmark-Plan-2012-12-21.pdf (accessed Sept. 30, 2013). |

| 9. | New Mexico Office of the Superintendent of Insurance, New Mexico Health Insurance Premium Summary 2014, http://nmhealthratereview.com/attachments/WebFormat_NMHI_2014.pdf (accessed Sept. 30, 2013). |

| 10. | Quigley, Winthrop, “Cost for Fed Health Insurance 5% More,” The Albuquerque Journal (June 21, 2013). |

| 11. | Avalere Health, Exchange Premium Analysis, Washington, D.C. (June 19, 2013). |

| 12. | New Mexico Human Services Department, New Mexico Health Insurance Exchange Advisory Task Force Recommendations, Santa Fe, N.M. (April 9, 2013). |

| 13. | New Mexico Health Insurance Exchange, approved minutes of June 7, 2013, Exchange Board meeting, http://www.nmhix.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/NMHIX_June-7-2013_ApprovedBoardMinutes.pdf (accessed Sept. 30, 2013). |

| 14. | Kenney, Genevieve M., et al., State and Local Coverage Changes under Full Implementation of the Affordable Care Act, prepared by the Urban Institute for the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Washington, D.C. (July 2013). |

| 15. | Buettgens, Matthew, John Holahan and Caitlin Carroll, Health Reform Across the States: Increased Insurance Coverage and Federal Spending on the Exchanges and Medicaid, The Urban Institute, Washington, D.C. (March 2011). Additional enrollment growth is expected as a result of eligible but unenrolled individuals enrolling in the program. |

Data Source

As part of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s (RWJF) State Health Reform Assistance Network initiative, the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC) examined commercial and Medicaid health insurance markets in eight U.S. metropolitan areas: Baltimore; Portland, Ore.; Denver; Long Island, N.Y.; Minneapolis/St. Paul; Birmingham, Ala.; Richmond, Va.; and Albuquerque, N.M. The study examined both how these markets function currently and are changing over time, especially in preparation for national health reform as outlined under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010. In particular, the study included a focus on the impact of state regulation on insurance markets, commercial health plans’ market positions and product designs, factors contributing to employers’ and other purchasers’ decisions about health insurance, and Medicaid/state Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) outreach/enrollment strategies and managed care. The study also provides early insights on the impact of new insurance regulations, plan participation in health insurance exchanges, and potential changes in the types, levels and costs of insurance coverage.

This primarily qualitative study consisted of interviews with commercial health plan executives, brokers and benefits consultants, Medicaid health plan executives, Medicaid/CHIP outreach organizations, and other respondents—for example, academics and consultants—with a vantage perspective of the commercial or Medicaid market. Researchers conducted 14 interviews in the Albuquerque market between April and July 2013. Additionally, the study incorporated quantitative data to illustrate how the Albuquerque market compares to the other study markets and the nation. In addition to a Community Report on each of the eight markets, key findings from the eight sites will also be analyzed in two publications, one on commercial insurance markets and the other on Medicaid managed care.