Managed Care and Care for the Poor: Mixed Results

Orange County, Calif.These two safety net hospitals have been strained financially by the state’s shift of Medi-caid beneficiaries into managed care plans, which began in 1995. In Orange County, CalOPTIMA negotiates capitated contracts with plans and physician hospital consortia on behalf of Medi-Cal, the state’s Medicaid program. CalOPTIMA has earned praise over the past several years for broadening access to providers-some 85 percent of the county’s physicians see Medi-Cal beneficiaries-and limiting spending.

CalOPTIMA has supported CHOC, UCIMC and other safety net providers by assigning beneficiaries who fail to select their own plan to one of the consortia that includes these providers. But many Medi-Cal beneficiaries have chosen CalOPTIMA plans and provider groups that do not include these safety net hospitals. To make up for losses on their Medi-Cal business, these hospitals are trying to boost their occupancy rates by targeting private-pay patients.

Another part of the safety net, the county’s public health department, is also affected by the movement to Medicaid managed care. A collateral study by MPR’s Rose Marie Martinez examined how Orange County and other areas’ public health departments in HSC’s tracking sites are coping with this shift. Some are reinventing themselves as partners to managed care entities. In Orange County, for example, the local health department has formal agreements with Medi-Cal HMOs to coordinate care and surveillance of 12 key public health areas, including tuberculosis and HIV control.

Meanwhile, the county is seeking to restructure how it provides required care to the uninsured who need medical services. CalOPTIMA has been chartered to administer the existing Orange County program for this population, the Medical Services for the Indigent (MSI) program, and has been working with the county to develop managed care principles for it. One problem is that the MSI program reportedly reimburses providers for less than one-fifth of the cost of the care they provide. As a step toward taking over the program, CalOPTIMA and the county are designing a pilot program to get better information on what proportion of the area’s 335,000 uninsured are medically indigent and what kind of health care services they might need.

A recent study by HSC senior researcher Peter J. Cunningham found that financial pressures on safety net providers may be having a negative effect on access to care for the low-income uninsured. Specifically, the study found that only 51 percent of all low-income uninsured persons had an ambulatory visit in the past year in high Medicaid managed care states, while 63 percent of their counterparts had such visits in states with low Medicaid managed care penetration. The study was based on the HSC 1996-1997 Household Survey.

While Medicaid managed care has been able to offer more choice to beneficiaries, it appears to be

contributing to the difficulties the low-income uninsured face in getting access to care. The broad

spectrum of safety net providers-among them free-care clinics, public and teaching hospitals, some

not-for-profit hospitals, physicians and others-have raised concerns that downward pressures on

reimbursement rates are contributing to the widening of the already existing holes in the safety

net. Advocates for the poor, along with a growing number of policy makers from different perspectives,

worry about who may be falling through.

"As you move toward a market that is more competitive, there is significant

unraveling of the longstanding system of cross-subsidies that have enabled doctors

and medical centers to devote time and revenue to providing care for the indigent."

Paul B. Ginsburg, HSC, The Wall Street Journal

The Relationship between Managed Care and Charity Care

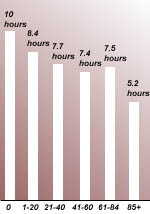

Recent HSC research shows that managed care may also be affecting physicians, an often unrecognized part of the safety net. Based on data from HSC’s Physician Survey, Peter J. Cunningham and colleagues found that physicians who derive most of their practice revenue from managed care provide 40 percent less charity care than those who receive relatively little revenue from managed care plans. The study also found that physicians who practice in areas with high managed care penetration provide less charity care than physicians in other areas, regardless of their own level of involvement with managed care.

Average Hours Physicians Spent Providing Charity Care during the Previous Month

Percent of Revenue Derived from Managed Care

Note: Estimates are computed from multivariate analysis that include other characteristics of physicians, physician practices and the market.

HSC Community Tracking Study,

Physician Survey, 1996-1997

"The evidence suggests that the holes in the safety net are getting bigger. In areas where managed care is more highly developed, it is more difficult for uninsured persons to get care."

Peter J. Cunningham, HSC

New York Times