Provider Systems Thrive in Robust Economy

Indianapolis, Indiana

Community Report No. 01

Fall 2000

Aaron Katz, Robert E. Hurley, Leslie A. Jackson, Timothy K. Lake, Ashley C. Short, J. Lee Hargraves

The Indianapolis health care market has shown remarkable stability over the past four years, despite such pressures as sharply rising premiums, a federal antitrust investigation and Medicare payment cuts. Preferred provider organizations (PPOs) remain the most popular form of managed care, and four major not-for-profit hospital systems, which also own some of the major health plans, continue to dominate the market, each with its own distinct geographic niche.

State and local health policy activity increased over the past four years, and by 2000, policy makers had expanded health insurance coverage, strengthened the safety net and enacted new insurance regulations. In contrast, employers have exerted little influence in the health care market.

Developing market trends include:

- Hospital systems target growth through affiliations outside Indianapolis,

joint ventures with physicians and competition for specialty services.

- With a tight labor market, employers accept steep

premium increases with little cost shifting to employees.

- Safety net providers are financially healthy due to Medicaid expansions and strong leadership.

- Hospital Systems Still Dominate, Compete at the Margins

- Hospital-Physician Relationships Shift Focus

- Stronger Managed Care Fails to Materialize

- Skepticism Marks Purchaser Strategies

- State Policies Help to Strengthen Safety Net

- Issues to Track

- Indianapolis’ Experience with the Local Health System, 1997 and 1999

- Background and Observations

Hospital Systems Still Dominate, Compete at the Margins

The four major systems are separated into mutually exclusive market areas, and each owns, in whole or part, health plans, hospitals and physician groups. This geographic separation and vertical integration have allowed the hospitals to engage in moderate levels of strategic innovation to retain market power without significant threats from potential competitors.

The hospital systems appear financially healthy, despite pressures from the 1997 Balanced Budget Act (BBA), which resulted in significant cuts in hospital revenues. The hospitals have responded by reducing operating costs and increasing other revenues. Their efforts to maintain market power focus on three major strategies:

- St. Vincent, Clarian and St. Francis

are expanding outside of Indianapolis

through network affiliations and acquisitions.

For example, St. Francis is at

the core of a seven-hospital system that

includes two facilities in Illinois. The

system added three of these hospitals in

the past year. This strategy is an attempt

to reinforce and shore up the referral-

and therefore revenue-base for the

systems’ tertiary hospitals.

- Some systems are expanding ambulatory

care services, often through joint

ventures with physician groups, both

within and outside the metropolitan

area. Ambulatory services are seen as

the main source of revenue growth

(especially for the commercially

insured) in the coming years and as

important access points into each

organization’s delivery system.

- The major systems continue to sponsor health plans and to have some risk-sharing contracts for health maintenance organization (HMO) products. Some see this ownership of plans as an important factor in keeping more tightly managed forms of health care from emerging in the market. However, continued efforts to consolidate ownership of these plans reportedly have ended, due to a Department of Justice investigation of alleged antitrust violations by the four hospital systems.

Until now, pressures leading to greater competition among hospital systems in some other markets have not had the same impact in Indianapolis. However, the four major hospital systems are pursuing strategic initiatives that have the potential for heating up competition. For example, St. Vincent, the market leader in cardiology, is bolstering its service capacities for this specialty, as well as pediatrics and obstetrics, in an apparent attempt to compete with Clarian, the traditional market leader. Community Hospitals has entered the cardiac game with its recent announcement to open a heart hospital, while St. Francis is expanding its ambulatory care services in areas that may compete directly with other providers.

Hospital-Physician Relationships Shift Focus

Three of the four major systems are actively engaged in joint ventures with single-specialty groups to develop new ambulatory surgery centers or other ambulatory services. The four hospital systems also are providing or considering management services to support independent physician practices. The hospitals continue to operate about 75 percent of the primary care practices in the area and are renegotiating contracts to add compensation methods that promote productivity.

Interest in contracting through physician-hospital organizations (PHOs) continues to decline, due to the area’s persistently low HMO penetration and lack of global risk contracting that these entities were designed to support. In addition, many risk-bearing networks have not grown large enough to develop the administrative and clinical decision-making systems necessary for managing risk effectively. Nevertheless, many physicians continue to participate, and PHOs have wide provider networks.

Consolidations among single-specialty practices strengthened their bargaining positions with health plans and provider systems between 1996 and 1998, and they continue to hold influential market positions. The Indianapolis market continues to lack large multispecialty groups or independent practice associations, in part because most primary care practices are owned by hospitals.

No major medical groups or other organizations have formed recently, although some existing groups have grown larger. For example, The Care Group, the area’s largest cardiology practice, doubled in size after an acquisition in 1999. With 83 cardiologists in 18 offices, plus 50 primary care physicians, The Care Group reportedly is one of the largest privately owned cardiology groups in the country. Likewise, Orthopaedics Indianapolis grew by two-thirds when it added 27 physicians to its practice in 1999 by purchasing small groups and hiring recently trained physicians. Because they work with physicians who came from competing group practices, such groups are facing management challenges of governance, compensation and practice patterns.

Stronger Managed Care Fails to Materialize

The balance of power among health plans-and between health plans and other sectors-has not changed appreciably. Plans view themselves as disadvantaged, given the lack of support from purchasers and what they see as disproportionate state regulatory burdens on HMOs. Without counter-pressure from purchasers, plans appear intent on improving their financial positions by increasing income through higher premiums rather than increasing revenues through higher enrollment. As a result, health plans have tended to avoid bidding wars with competitors-a situation unlikely to be unique to Indianapolis, as the underlying insurance cycle has led to across-the-board premium increases.

The small number of national plans active in Indianapolis dwindled further with the departure of Principal (after it was acquired by Coventry Health Care) and the consolidation of Aetna and Prudential. With roughly 40,000 lives added in the Prudential acquisition and the launching of its new HMO product in April 2000, Aetna continues to be the lightning rod for local concerns about a national plan "invading" the market. Meanwhile, Anthem, the multistate Blue Cross and Blue Shield company that grew out of the Indiana Blues plan, remains a major player among Indianapolis health plans. It has continued out-of-market acquisitions and has made a concerted effort to consolidate a number of operational functions at its new headquarters in downtown Indianapolis. These steps are expected to improve customer and provider relations and bring greater uniformity to Anthem’s multiple services and product lines that have emerged in the course of its acquisitions.

The small role of national plans in Indianapolis reportedly spurred the Justice Department in early 2000 to investigate whether the four major hospital systems have engaged in antitrust activities to keep such plans out. Few observers, however, think the probe will reveal antitrust violations or have any long-term effects.

Provider-sponsored health plans have undergone significant consolidation with the creation of The Health Care Group. This enterprise-87 percent owned by Clarian, with Community Hospitals and two other hospitals owning minority shares-has combined PPOs statewide and achieved some limited HMO consolidation, largely around Clarian’s plan, M-Plan. Discussions between The Health Care Group and Sagamore Health Network, a PPO owned principally by St. Francis and St. Vincent, reportedly have ended because of concerns about the antitrust probe.

The lack of interest in HMOs has stalled growth of risk arrangements with providers. A number of organizations discussed such arrangements, but few actually pursued them. Moreover, major players like Anthem prefer individual contracts with providers rather than contracts with larger networks for financial and operational reasons. In general, because so many people in the area are covered under PPOs and non-HMO, self-insured arrangements, few premium dollars are available for risk contracts.

Rising pharmaceutical costs are putting financial pressure on all market sectors, but the problem is most acute for plans because both providers and purchasers want to shift or return more risk to the HMOs. Other than triple-tiered copayments, no solutions to increased utilization and more expensive drugs are in the offing. Since care management is relatively underdeveloped in Indianapolis, disease management programs are unlikely to relieve rising prescription drug costs.

Medicare managed care was insignificant in Indianapolis before the BBA, and recent developments suggest a further decline, despite the Medicare+Choice program. Sagamore, a new entrant in the Medicare market, is the only remaining risk plan. Anthem and Maxicare have announced their intent to withdraw from Medicare, and M-Plan converted to a cost contract several years ago. Growth in Medicare+Choice is unlikely given consumers’ and providers’ disinterest.

Despite low HMO enrollment, state policy makers continue to focus on managed care regulation. In 2000, the state amended a 1997 patient protection law requiring HMOs to create and maintain grievance procedures, including external reviews, and the state Department of Insurance (DOI) to certify independent review organizations. In 1999, Indiana enacted mandated benefits for cancer screening, dental anesthesia and newborn hearing screening; banned prescription drug formularies; and enacted an any-willing- provider law for PPOs. DOI, the state agency that oversees managed care and provider complaints, is newly charged with publishing health plan comparisons, as well.

Skepticism Marks Purchaser Strategies

Indianapolis has relatively few purchaser innovations. With the tight labor market, employers are reluctant to switch their employees to more restrictive forms of care or pass along cost increases. Employers and consumers continue to have few resources for evaluating plans and providers. Although the Indiana Employers’ Health Care Coalition published its provider profiling findings, the results were met with skepticism due to its data collection methods and failure to use a nationally recognized survey. On the other hand, plans appeared to welcome the results of HMO profiling by the Roundtable, a group formed by Eli Lilly and other large businesses in 1997, but the results have not been released to the public. Plans do not think reporting efforts have influenced purchasing practices in detectable ways.

A major development among employers in the last two years was the merger of the Indiana Employers’ Health Care Coalition and the Roundtable. The new organization, the Indiana Employers’ Quality Health Alliance, includes 20 firms representing 80,000 employees. The Alliance plans to continue its provider and HMO profiling efforts and is moving forward with group purchasing efforts. Five employers have already agreed to offer HMO options to their employees exclusively through the Alliance, which has developed standard benefits, sent out requests for proposals for group purchasing, received responses from seven health plans and expects coverage to begin by January 2001. Some employers reportedly have expressed interest in the Alliance, while others are taking a wait-and-see approach before joining. So far, it has been met with general skepticism based on the limited impact previous employers’ collective initiatives have had in Indianapolis.

State Policies Help to Strengthen Safety Net

SCHIP’s success is attributed to innovative outreach strategies and a commitment to mainstream the image of SCHIP/Hoosier Healthwise. The language in the program’s literature refers to "affordable" not "free,""members" not "recipients," medical services" not "public assistance." Enrollees get a Hoosier Healthwise insurance card, not an Indiana Medicaid card. Moreover, outreach has largely been decentralized, engaging nearly every health care organization in the Indianapolis area. This has led to new collaborations among safety net providers and other organizations that extend beyond SCHIP. For example, under the auspices of HealthNet Community Health Centers, the four major hospital systems, Wishard Health Services, Indiana University Medical Group-Primary Care, the Health Foundation of Indianapolis and six school districts have initiated the School Wellness Collaboration to provide health services in area schools.

SCHIP has helped safety net providers grow stronger financially, largely by paying for people who formerly required charity care. At HealthNet’s five clinics, 35 to 40 percent of all patients were self-pay before SCHIP, dropping to 25 percent after SCHIP began. The percentage of Medicaid patients correspondingly rose from 40 percent to 52 percent. Wishard Advantage, a successful managed care program that provides access to medical services to the uninsured, enrolled about 5,000 children in SCHIP who had been served for free. A statewide increase of $100 million per year in disproportionate share hospital payments and the continued support of Indianapolis property taxpayers ($50 million per year) also have aided the safety net’s financial status. Finally, the state legislature allocated its entire $130 million tobacco settlement to health services, including $25 million for community clinics and $1.5 million for local public health agencies.

From this strong base, safety net providers appear poised to expand. HealthNet expects to replace at least two of its clinics in the near future, using tobacco settlement funds and foundation grants. In addition, it has entered into an agreement with Wishard to participate in the Wishard Advantage program. HealthNet will receive additional funds to provide primary care to its patients, while Wishard will provide specialty and hospital services. Wishard is seeking additional partnerships to expand the program statewide.

Issues to Track

As the market continues to unfold, the following issues will be important to track:

- What effects will rising premiums and a

potentially weakening economy have on

employee health benefits and cost sharing,

managed care enrollment and the

success of Hoosier Healthwise?

- Will single-specialty physician organizations

continue to expand, and how will

their relationships with hospitals and

health plans evolve?

- Will competition among the four dominant

hospital systems heat up over

ambulatory surgery centers or specialty

services, and will this lead to building

excess capacity?

- How will consumers, purchasers and

health plans respond to rising prescription

drug costs, and how will that

response affect risk contracts between

plans and providers?

- Will the Wishard Advantage program

for the uninsured continue to expand in

Indianapolis and elsewhere in the state?

- What effects will the newly formed Indiana Employers’ Quality Health Alliance have on provider and plan performance in the Indianapolis marketplace?

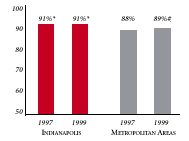

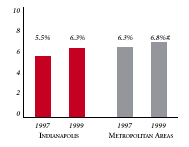

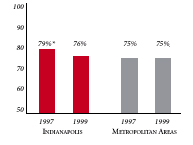

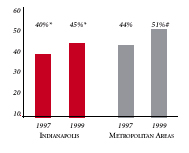

Indianapolis’ Experience with the Local Health System, 1997 and 1999

| PERSONS SATISFIED WITH THE HEALTH CARE THEY RECEIVED IN THE LAST 12 MONTHS | PERSONS WHO DID NOT GET NEEDED MEDICAL CARE IN THE LAST 12 MONTHS |

|

|

| PHYSICIANS AGREEING THAT IT IS POSSIBLE TO PROVIDE HIGH-QUALITY CARE TO THEIR PATIENTS | PERSONS WITH INSURANCE THAT REQUIRES GATEKEEPING |

|

|

| * Site value is significantly different from the mean for

metropolitan areas over 200,000 population. # Statistically significant difference between 1997 and 1999 at p< .05. The information in these graphs comes from the Household and Physician Surveys conducted in 1996-1997 and 1998-1999 as part of HSC’s Community Tracking Study. |

|

Background and Observations

| Indianapolis Demographics | |

| Indianapolis | Metropolitan areas above 200,000 population |

| Population, July 1, 19991 1,536,665 |

|

| Population Change, 1990-19992 | |

| 11% | 8.6% |

| Median Income3 | |

| $27,996 | $27,843 |

| Persons Living in Poverty3 | |

| 11% | 14% |

| Persons Age 65 or Older3 | |

| 12% | 11% |

| Sources: 1. U.S. Bureau of Census, 1999 Community Population Estimates 2. U.S. Bureau of Census, 1990 & 1999 Community Population Estimates 3. Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1998-1999 |

|

| Health Insurance Status | |

| Indianapolis | Metropolitan areas above 200,000 population |

| Persons under Age 65 with No Health Insurance1 | |

| 14% | 15% |

| Children under Age 18 with No Health Insurance1 | |

| 10% | 11% |

| Employees Working for Private Firms that Offer Coverage2 | |

| 86% | 84% |

| Average Monthly Premium for Self-Only Coverage under Employer-Sponsored Insurance2 | |

| $178 | $181 |

| Sources: 1. Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1998-1999 2. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Employer Health Insurance Survey, 1997 |

|

| Health System Characteristics | |

| Indianapolis | Metropolitan areas above 200,000 population |

| Staffed Hospital Beds per 1,000 Population1 | |

| 3.3 | 2.8 |

| Physicians per 1,000 Population2 | |

| 2.5 | 2.3 |

| HMO Penetration, 19973 | |

| 23% | 32% |

| HMO Penetration, 19994 | |

| 23% | 36% |

| Sources: 1. American Hospital Association, 1998 2. Area Resource File, 1998 (includes nonfederal, patient care physicians, except radiologists, pathologists and anesthesiologists) 3. InterStudy Competitive Edge 8.1 4. InterStudy Competitive Edge 10.1 |

|

The Community Tracking Study, the major effort of the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC), tracks changes in the health system in 60 sites that are representative of the nation. Every two years, HSC conducts surveys in all 60 communities and site visits in 12 communities. The Community Report series documents the findings from the third round of site visits. Analyses based on site visit and survey data from the Community Tracking Study are published by HSC in Issue Briefs, Data Bulletins and peer-reviewed journals. These publications are available at www.hschange.org.

Aaron Katz, University of Washington; Robert E. Hurley, Virginia Commonwealth University; Leslie Jackson, HSC; Timothy K. Lake, Mathematica Policy Research, Inc.; Ashley Short, HSC; and J. Lee Hargraves, HSC

President: Paul B. Ginsburg

Director of Site Visits: Cara S. Lesser

Director of Public Affairs: Ann C. Greiner

Editor: The Stein Group