Race, Ethnicity and Preventive Services:

No Gains for Hispanics

Issue Brief No. 34

January 2001

J. Lee Hargraves

![]() hree years ago, the Clinton administration initiated multiple

efforts to identify and eliminate health disparities among various populations,

including ethnic minority groups. Recent findings from the Community Tracking

Study Household Survey show that between 1997 and 1999 there was an increase

in the percentage of white and African American persons receiving preventive

care—such as mammography screening among women and physicians counseling cigarette

smokers to quit—but that there was no such increase in preventive measures for

Hispanics. If policy makers want to remove disparities in health status based

on race and ethnicity, they need to promote preventive care for minorities and

monitor progress by regularly measuring preventive care indicators. This Issue

Brief focuses on change in key preventive care indicators between 1997 and 1999.

hree years ago, the Clinton administration initiated multiple

efforts to identify and eliminate health disparities among various populations,

including ethnic minority groups. Recent findings from the Community Tracking

Study Household Survey show that between 1997 and 1999 there was an increase

in the percentage of white and African American persons receiving preventive

care—such as mammography screening among women and physicians counseling cigarette

smokers to quit—but that there was no such increase in preventive measures for

Hispanics. If policy makers want to remove disparities in health status based

on race and ethnicity, they need to promote preventive care for minorities and

monitor progress by regularly measuring preventive care indicators. This Issue

Brief focuses on change in key preventive care indicators between 1997 and 1999.

Preventive Care Services

![]() roviding preventive care services

is a key aim of primary care,

and timely delivery of these services

is vital for improving the health of

Americans. Preventive care screening

and immunizations can promote

early diagnosis and treatment of disease

and/or prevent serious illness.

Disparities in receiving these services

among racial and ethnic minorities,

compared with white Americans, contribute

to disparities in health status.

roviding preventive care services

is a key aim of primary care,

and timely delivery of these services

is vital for improving the health of

Americans. Preventive care screening

and immunizations can promote

early diagnosis and treatment of disease

and/or prevent serious illness.

Disparities in receiving these services

among racial and ethnic minorities,

compared with white Americans, contribute

to disparities in health status.

A minimum requirement for getting preventive care usually involves a visit with a physician. Other important indicators of access to preventive care are mammograms, flu shots and smoking cessation counseling by a physician.

The 1996-1997 and 1998-1999 Household Surveys provide information on general measures of preventive care that can be used to compare services among racial and ethnic groups. These measures apply to specific conditions or subgroups in which disparities are known to exist and where benefits of preventive care have been demonstrated. This Issue Brief describes physician visits among racial or ethnic groups and examines differences using three preventive care indicators during both survey periods, focusing on what changed over time for each group.

Comparisons by Race and Ethnicity

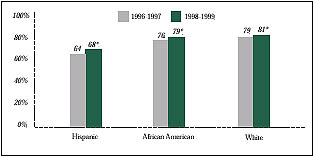

![]() n 1998-1999, approximately 80 percent of white and African American

persons and only 68 percent of Hispanic persons reported seeing a physician

in the last year (see Figure 1). Among all three groups, reports of seeing a

physician once during a 12-month period have increased, and previously observed

disparities have narrowed. The difference in physician visits between white

and African American patients identified in the 1996-1997 survey has almost

disappeared, and the gap between white and Hispanic patients has narrowed somewhat.

Hispanics were 6 percent more likely to report having seen a physician during

the year in the 1998-1999 survey, but they still fall behind whites and African Americans.

n 1998-1999, approximately 80 percent of white and African American

persons and only 68 percent of Hispanic persons reported seeing a physician

in the last year (see Figure 1). Among all three groups, reports of seeing a

physician once during a 12-month period have increased, and previously observed

disparities have narrowed. The difference in physician visits between white

and African American patients identified in the 1996-1997 survey has almost

disappeared, and the gap between white and Hispanic patients has narrowed somewhat.

Hispanics were 6 percent more likely to report having seen a physician during

the year in the 1998-1999 survey, but they still fall behind whites and African Americans.

Given these disparities in physician visits, it is not surprising that there are differences among the three groups in receiving specific preventive care services.

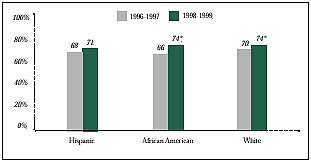

Mammography Rates. Early detection of breast cancer leads to dramatically improved treatment outcomes. Poorer cancer survival rates have long been observed for racial and ethnic Americans. In addition, these outcome disparities have been linked to delays in the detection of cancer.

Mammography rates increased significantly between the two surveys for both African American and white women (see Figure 2). Moreover, 1998-1999 estimates indicate that in the past two years African American and white women over age 50 report receiving a mammogram at the same rate-74 percent-whereas earlier there was a four percentage point difference. These changes also reflect a continuing trend in increasing mammography rates by African American and white women.1

In contrast, Hispanic women have fallen behind both African American and white women in screening for breast cancer. In both Household Surveys, fewer than 71 percent of eligible Hispanic women reported getting a mammogram in the past two years.

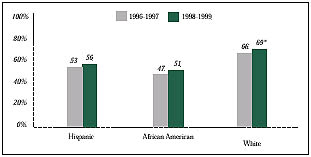

Adults Getting Flu Shots. Older persons are especially vulnerable to the effects of influenza, so flu shots are increasingly recommended for certain vulnerable groups, particularly those age 65 and older. According to the 1998-1999 survey, nearly 70 percent of older white persons received flu shots, compared with slightly more than half of Hispanics and African Americans (see Figure 3). The number of older whites who reported getting flu shots rose slightly during the last two years, while there were no significant increases among African Americans and Hispanics. Although disparities persist between whites and others, the gap has not widened significantly.

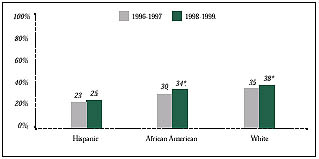

Counseling Patients to Stop Smoking. Smoking cessation is a major goal to improve the nation’s overall health. Smoking is a major modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease, one of the six areas in the federal government’s effort to remove racial and ethnic disparities in health. Members of all racial and ethnic groups are very interested in quitting smoking, and cigarette smokers are more likely to stop if their doctor advises them to quit. Physicians counseling their patients who smoke to stop is one of several very effective approaches to reduce cigarette smoking.

In 1998-1999, significantly more African American and white smokers than Hispanic smokers were encouraged to quit by their physicians (see Figure 4). Compared to the 1996-1997 survey, African Americans and whites who smoke were more likely than Hispanics to report being told by their physicians to stop. Among Hispanics, virtually no change was found in this behavioral intervention. As in 1996-1997, white cigarette smokers were most likely and Hispanic smokers least likely to report being advised by their physicians to quit.

Figure 1

Persons Visiting a Physician Last Year

* Significant change from 1996-1997 at p< .05 level.

Source: Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1996-1997 and 1998-1999

Figure 2

Women over 50 Getting a Mammogram in the Last Two Years

* Significant change from 1996-1997 at p< .05 level.

Source: Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1996-1997 and 1998-1999

Figure 3

Adults 65 and Older Getting a Flu Shot in the Last 12 Months

* Significant change from 1996-1997 at p< .05 level.

Source: Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1996-1997 and 1998-1999

Figure 4

Persons Counseled by a Physician to Stop Smoking

* Significant change from 1996-1997 at p< .05 level.

Source: Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1996-1997 and 1998-1999

Implications

![]() ationwide efforts to promote preventive

care may be paying off, as indicated by

increases in screening for breast cancer, flu

shots and counseling to stop smoking. These

increases between 1997 and 1999 are likely

the result of many organizations’ efforts,

including government agencies, health plans

and accreditation organizations.

ationwide efforts to promote preventive

care may be paying off, as indicated by

increases in screening for breast cancer, flu

shots and counseling to stop smoking. These

increases between 1997 and 1999 are likely

the result of many organizations’ efforts,

including government agencies, health plans

and accreditation organizations.

Nevertheless, the picture is less positive for Hispanics. The striking finding from the two Household Surveys is the disparity in preventive care for Hispanics and this group’s lack of improvement on many measures between 1997 and 1999. The low use of preventive services by Hispanics may be the result of various factors, including lack of health insurance, language barriers and/or other cultural issues. For example, Hispanics (48 percent) are much more likely than African Americans (6.4 percent) or whites (4.7 percent) to have been born outside the United States.2 The combined effects of these differences may make increasing preventive care rates for Hispanics more difficult.

African Americans, in contrast, have seen improvements in several measures. There is now parity for getting a mammogram among African American and white women over age 50. However, African Americans still lag behind white Americans in other preventive measures, such as flu shots for those over 65. This particular disparity endures, even among persons with similar coverage under Medicare.

In some cases, insurance coverage expansions may help reduce disparities among racial and ethnic groups, but expansions alone may not eliminate such differences completely. To achieve further progress in eliminating disparities among racial and ethnic minorities, health plans and providers could identify ethnic groups for monitoring of preventive care services and/or intervention. Policy makers might encourage health care organizations to report on their progress in reducing disparities in access to and use of preventive care.

Health plans and providers may also develop and/or expand programs that enhance use of culturally appropriate preventive services that address issues related to distrust of the health care system. Awareness of the role of culture in medical care extends beyond translation of educational materials into multiple languages. Policy makers can learn from existing programs that consider historical and cultural diversity among ethnic groups. Building trust among minority groups can be accomplished by educating health care providers to consider their patients’ unique perspective toward medical care.

These efforts may increase due to the recently signed Health Care Fairness Act that establishes the National Center for Research on Minority Health and Health Disparities, which will provide funding to develop continuing education curricula, train minority physicians, foster cultural competency and monitor progress in reducing disparities.

Data Sources

![]() his Issue Brief presents findings from the first and second

Household Surveys, nationally representative telephone surveys of the civilian,

noninstitutionalized population conducted in 1996- 1997 and 1998-1999 by the

Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC) as part of the Community Tracking

Study. Each survey included interviews with more than 60,000 persons and 33,000

families. Estimates for the measures were weighted to represent the U.S. population.

All comparisons and differences described in the text are statistically significant

at p< .05 level.

his Issue Brief presents findings from the first and second

Household Surveys, nationally representative telephone surveys of the civilian,

noninstitutionalized population conducted in 1996- 1997 and 1998-1999 by the

Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC) as part of the Community Tracking

Study. Each survey included interviews with more than 60,000 persons and 33,000

families. Estimates for the measures were weighted to represent the U.S. population.

All comparisons and differences described in the text are statistically significant

at p< .05 level.

Three racial or ethnic groups are compared: Hispanic, African American and white. African American refers to all non-Hispanic African Americans, and white refers to all non-Hispanic white Americans.

Notes

1. U.S. Census Bureau. The Official Statistics, Statistical Abstract of the United States: 1998, Table 199, p. 133 (October 14, 1998). Note: Mammography rates were based on the National Health Interview Survey.

2. Hajat A. Health Outcomes among Hispanic Subgroups: Data from the National Health Interview Survey, 1992-1995, p. 310. Vital Health and Statistics of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics (2000).

ISSUE BRIEFS are published by Health System Change.

President: Paul B. Ginsburg

Director of Public Affairs: Ann C. Greiner

Editor: The Stein Group