Market Instability Puts Future of HMOs in Question

Seattle, Washington

Community Report No. 03

Winter 2001

Glen P. Mays, Sally Trude, Lawrence P. Casalino, Patricia Lichiello, Leslie A. Jackson, Ashley C. Short

Over the past two years, hospital and physician contract disputes with health plans have disrupted the Seattle health care market, causing considerable instability in provider networks and threatening the viability of many managed care products. In 1998, expected growth in health maintenance organization (HMO) enrollment attracted national health plans to Seattle, raising concerns about potential erosion of the health care market’s local nature. Since then, two national plans have left the area after failing to achieve substantial market share. Meanwhile, hospitals and physicians have abandoned risk-based contracting with health plans, leaving the future of HMOs in doubt.

Other significant developments over the past two years include:

- Two major hospital systems consolidated, increasing

their negotiating leverage with physicians and health

plans.

- Several large physician organizations failed financially,

further jeopardizing risk-based contracting.

- Many health plans dropped their Medicaid, Medicare and individual insurance products, leaving dwindling insurance options for populations they serve.

- Contract Disputes Led to Instability in Provider Networks

- Providers Abandon RiskContracting, Cost Control Erodes

- Hospitals Gain Leverage with Physicians and Health Plans

- Insurance Options Dwindle for the Poor, Elderly and Uninsured

- Budget Pressures Drive Health Policy Making

- Issues to Track

- Seattle’s Experience with the Local Health System, 1997 and 1999

- Background and Observations

Contract Disputes Led to Instability in Provider Networks

The rash of disputes and terminations in Seattle was precipitated largely by providers’ poor financial performance under contracts with health plans. Risk-bearing contracts had failed to deliver the revenue that many providers had anticipated. At the same time, those paid under fee-for-service arrangements suffered as well because fee schedules remained flat, while provider expenses for labor, pharmaceuticals and new technology were rising. Poor profitability and high overhead costs led to the insolvency of several large physician organizations, adding to the market’s instability.

Seattle’s providers began to push back on health plans during 1999 and 2000 by terminating or assertively renegotiating their contracts. The growing popularity of open-ended PPO and POs insurance products strengthened providers’ negotiating leverage, because these products allowed patients to see out-of-plan providers.

One of the earliest and most visible provider contracting disputes occurred in 1999, when three large medical groups and two major hospital systems terminated their contracts with PacifiCare, citing inadequate capitation rates and dissatisfaction with claims payment and information management. The organizations involved-600-physician University of Washington Physicians, 30-physician Evergreen Medical Group and 300- physician Northwest Health Partners, along with the University of Washington Medical Center and Virginia Mason Medical Center-were among the most prominent providers in the region.

In another highly publicized dispute, 150 specialists cancelled their contracts with Regence BlueShield because of the plan’s intention to adopt Medicare’s recent resource-based relative value scale, thereby lowering payment rates for most surgical services. One large employer actively pressured Regence BlueShield to bring the specialist groups back into the network, diminishing the health plan’s leverage with these providers.

As a result of this recent turmoil, network stability has become an increasingly important element of health plan competition in Seattle. Several large employers have established performance guarantees regarding network stability in their contracts with health plans, and provider retention has become a more important consideration in health plans’ contracts with providers. This trend promises even greater leverage for Seattle providers in their future negotiations with health plans.

Providers Abandon Risk Contracting, Cost Control Erodes

The dissolution of several large physician organizations hastened the move away from risk contracting. Two of Seattle’s largest individual practice associations (IPAs), Cascade IPA and Puget Sound Physicians’ Association, failed financially and were disbanded in early 2000. In addition, the owners of the Seattle market’s largest medical group, Medalia Health Care, drastically cut the group’s size through a series of practice sales in 1999 and 2000, creating several smaller medical groups. Failure of these prominent physician organizations reduced the opportunities for risk contracting and contributed to providers’ fears about the potential consequences of these arrangements.

In response to physicians’ resistance to risk, several health plans in Seattle have launched new contracting arrangements designed to limit the financial risk borne by providers while retaining some incentives for efficient clinical practice. PacifiCare of Washington, for example, took over administration of two large IPAs when they became insolvent in early 2000, moving them from a full-risk capitated payment arrangement to a modified fee-for-service payment schedule. The fee schedule is adjusted up or down, depending on the physicians’ collective utilization experience during the preceding three months. Utilization targets, as well as maximum and minimum fee schedules, are established through annual collective negotiations with the group of physicians. Regence BlueShield has negotiated a similar contracting arrangement with this same group. Whether these new arrangements with providers are effective in controlling health care utilization and costs remains to be seen.

Hospitals Gain Leverage with Physicians and Health Plans

Some fear that the Swedish-Providence merger will have unintended consequences for the uninsured. Before the consolidation, Providence and its primary care clinics had been considered important sources of charity care in Seattle. Because the consolidation agreement did not guarantee that Swedish would keep Providence facilities open and intact, some respondents questioned whether the agreement might lead to a reduction in safety-net capacity within the community.

Others speculate that the acquisition gives Swedish the additional capacity necessary to accommodate growing inpatient volume. Hospital competition in Seattle has been limited to some extent over the past two years by inpatient capacity constraints. All three major hospital systems have been forced to close admissions periodically due to full occupancy. To address this problem, the University of Washington has taken steps to increase clinical capacity by establishing a number of new clinical facilities in partnership with other organizations, including a regional cancer center, a heart institute and an outpatient surgery center. These expansions could help to meet growing inpatient demand in the market and may spur more competition between the University of Washington and Swedish hospital systems.

The two hospital systems also have continued to compete for a more profitable patient mix by strengthening specialty service lines such as cardiology, oncology and orthopedics. Both the Swedish and University of Washington hospital systems have developed strategic alliances with suburban Seattle community hospitals to capture additional referral volume for specialty service lines. Under these arrangements, intensive services such as cardiac surgery are delivered at the dominant hospitals, while supporting services, such as diagnostic and rehabilitative care, are performed at the suburban hospitals. By delivering intensive services only at the high-volume hospitals, these arrangements may improve clinical quality and patient outcomes. Moreover, these arrangements may allow the two dominant hospital systems to strengthen their negotiating leverage with health plans and specialists further and to reduce competition from the smaller suburban facilities.

Insurance Options Dwindle for the Poor, Elderly and Uninsured

Medicaid. Several health plans have reduced or discontinued their participation in Healthy Options, the state’s Medicaid managed care program, and there are concerns that access to care may decline as a result. Over the past two years, the state has taken aggressive steps to contain health care costs in its Healthy Options program, including establishing maximum allowable premium levels for its 2001 health plan contracts. Citing an inability to secure provider participation under the allowable premium rates, Regence BlueShield withdrew completely from the program, despite its status as one of the largest participating plans, with more than 50,000 Healthy Options members statewide. Two other large plans withdrew from the program in Snohomish County for the same reason, and a fourth plan, QualMed, withdrew from Healthy Options when it left the market altogether. Although the entry of a Medicaid-only plan helped to offset these withdrawals, Healthy Options recipients were left with five participating plans in King County and only one in Snohomish County as of January 2001.

The unwillingness of Seattle providers to enter into risk contracts also has contributed to the withdrawal of commercial plans from Healthy Options. Commercial plans typically have been unwilling to participate in public programs without substantial risk-sharing from providers. As risk-sharing has declined in Seattle, Medicaid enrollment has become increasingly concentrated in Medicaid-only plans, such as Molina Health Care and the Community Health Plan of Washington, a plan formed by community health centers. Both of these Medicaid-only plans rely heavily on safety net providers for delivery of care. The withdrawal of plans with broader provider networks jeopardizes one of the program’s original goals-expanding low-income Medicaid beneficiaries’ access to private providers.

Medicare. Plan participation in Medicare has also declined precipitously since 1998, dramatically reducing choices for Medicare beneficiaries. In 2000, six of the eight participating plans in Seattle announced their intention to withdraw from the Medicare+Choice program, leaving seniors with only two Medicare managed care plans statewide. The possibility of severe capacity constraints has raised serious doubts about Seattle’s seniors’ continued access to managed care options. The two plans still participating in the Medicare+Choice program have reduced their Medicare service areas over the past two years, citing their inability to develop sufficient provider networks with the low payment rates offered through the Medicare+Choice program. Both plans also have experienced reductions in their Medicare+Choice provider networks due to hospital and physician contract terminations.

Individual Insurance Market. The individual insurance market in Seattle has experienced considerable turbulence since 1998, as well. Washington State policy makers phased out the component of the state’s Basic Health Plan that offered insurance to individuals and families with incomes too high to qualify for subsidized coverage. People who lost coverage through this policy change were expected to obtain insurance coverage in the individual market. During 1999, however, the three major insurance carriers that sold individual insurance policies in Washington State closed their products to new enrollment because of financial losses. Plans attributed their losses to rate-setting limits and adverse selection stemming from state-mandated limits on waiting periods.

In an effort to preserve access to insurance coverage, Washington State opened its high-risk health insurance pool to all state residents who were unable to purchase individual policies. In early 2000, the state legislature passed a law designed to encourage the state’s insurance carriers to reenter the individual insurance market. The new legislation removed the state insurance commissioner’s authority to review and deny rates for individual insurance products, and it extended the maximum waiting period for preexisting conditions to nine months. The law also permitted health plans to reject coverage for the sickest 8 percent of applicants, using a health status risk-assessment tool developed by the state, and to channel these applicants into the state’s high-risk insurance pool. The legislation was viewed as an important victory for the health insurance lobby, and all three insurance carriers resumed selling individual insurance policies in December 2000, after the reforms were implemented. Concerns remain that individuals without employer-sponsored coverage may not be able to afford insurance policies now that the state’s rate-approval authority has been removed.

Budget Pressures Drive Health Policy Making

A 1993 state ballot initiative (Initiative 601) imposed a spending cap that has prevented state health care spending from keeping pace with the steady growth in underlying health care costs. Over the past two years, the spending cap has forced state policy makers to take aggressive steps to constrain payment rates for health plans and providers participating in government health programs such as Healthy Options and the Basic Health Plan. State cost-containment efforts have hastened the exit of commercial health plans and private providers from government health programs, raising concerns about access to main-stream medical providers for Seattle’s low-income populations.

The effect of another state ballot initiative passed in 1999 (Initiative 695) was to eliminate a significant permanent funding source for local public health services. This initiative has prompted public health agencies to find new sources of funding and develop new service delivery arrangements. King County’s local public health agency, for example, experienced a $1.2 million budget cut in 2000 because of the initiative. The agency responded by cutting staff, reducing its primary care services and developing alliances with private providers to ensure access to care.

Safety net providers for the uninsured have remained strong in Seattle, despite state budget pressures. Community health centers and other safety net clinics have expanded their revenue base through aggressive efforts to enroll previously uninsured patients in public insurance programs such as Healthy Options and the State Children’s Health Insurance Program. Moreover, federal funding available to federally qualified health centers has helped these providers avoid financial difficulties. Nonetheless, there are concerns that continued state efforts to constrain Medicaid and Basic Health Plan payments to health plans and providers may begin to erode funding for safety net providers. Similarly, there are concerns that the continued exodus of private plans and providers from government health insurance programs eventually may overwhelm the capacity of Seattle’s safety net providers to serve both publicly insured and uninsured populations.

Issues to Track

As the market continues to unfold, the following issues will be important to track:

- Will health plans’ provider networks

and prices stabilize?

- Will traditional HMOs remain viable in

the Seattle market? How will plans that

specialize in HMOs respond if these

products continue to decline?

- How will diminishing health plan participation

in public programs affect

access to health care for seniors and

low-income populations?

- What impact will recent state insurance

reforms have on health insurance

coverage for individuals without

employer-sponsored coverage?

- How will hospital consolidation and the dismantling of physician organizations affect costs and access to care?

Seattle’s Experience with the Local Health System, 1997 and 1999

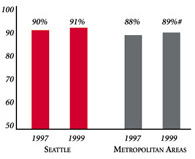

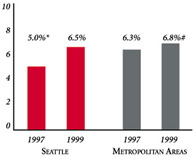

| PERSONS SATISFIED WITH THE HEALTH CARE THEY RECEIVED IN THE LAST 12 MONTHS | PERSONS WHO DID NOT GET NEEDED MEDICAL CARE IN THE LAST 12 MONTHS |

|

|

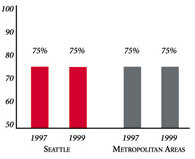

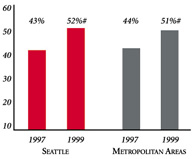

| PHYSICIANS AGREEING THAT IT IS POSSIBLE TO PROVIDE HIGH-QUALITY CARE TO THEIR PATIENTS | PERSONS WITH INSURANCE THAT REQUIRES GATEKEEPING |

|

|

|

* Site value is significantly different from the mean for metropolitan areas over 200,000 population. # Statistically significant difference between 1997 and 1999 at p< .05. The information in these graphs comes from the Household and Physician Surveys conducted in 1996-1997 and 1998-1999 as part of HSC’s Community Tracking Study. |

|

Background and Observations

| Seattle Demographics | |

| Seattle | Metropolitan areas above 200,000 population |

| Population, July 1, 19991 2,334,934 |

|

| Population Change, 1990-19992 | |

| 15% | 8.6% |

| Median Income3 | |

| $34,566 | $27,843 |

| Persons Living in Poverty3 | |

| 10% | 14% |

| Persons Age 65 or Older3 | |

| 12% | 11% |

| Sources: 1. U.S. Bureau of Census, 1999 Community Population Estimates 2. US Bureau of Census, 1990 & 1999 Community Population Estimates 3. Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1998-1999 | |

| Health Insurance Status | |

| Seattle | Metropolitan areas above 200,000 population |

| Persons under Age 65 with No Health Insurance1 | |

| 8.6% | 15% |

| Children under Age 18 with No Health Insurance1 | |

| 5.2% | 11% |

| Employees Working for Private Firms that Offer Coverage2 | |

| 85% | 84% |

| Average Monthly Premium for Self-Only Coverage under Employer-Sponsored Insurance2 | |

| $183 | $181 |

| Sources: 1. Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1998-1999 2. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Employer Health Insurance Survey, 1997 |

|

| Health System Characteristics | |

| Seattle | Metropolitan areas above 200,000 population |

| Staffed Hospital Beds per 1,000 Population1 | |

| 1.6 | 2.8 |

| Physicians per 1,000 Population2 | |

| 2.5 | 2.3 |

| HMO Penetration, 19973 | |

| 29% | 32% |

| HMO Penetration, 19994 | |

| 20% | 36% |

| Sources: 1. American Hospital Association, 1998 2. Area Resource File, 1998 (includes nonfederal, patient care physicians, except radiologists, pathologists and anesthesiologists) 3. InterStudy Competitive Edge 8.1 4. InterStudy Competitive Edge 10.1 |

|

The Community Tracking Study, the major effort of the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC), tracks changes in the health system in 60 sites that are representative of the nation. Every two years, HSC conducts surveys in all 60 communities and site visits in 12 communities. The Community Report series documents the findings from the third round of site visits. Analyses based on site visit and survey data from the Community Tracking Study are published by HSC in Issue Briefs, Data Bulletins and peer-reviewed journals. These publications are available at www.hschange.org.

Glen P. Mays, Mathematica Policy Research, Inc.

Sally Trude, HSC

Lawrence P. Casalino, University of Chicago

Patricia Lichiello, University of Washington

Leslie A. Jackson, HSC

Ashley C. Short, HSC

President: Paul B. Ginsburg

Director of Site Visits: Cara S. Lesser

Director of Public Affairs: Ann C. Greiner

Editor: The Stein Group