Insurance Coverage & Costs

Access to Care

Uninsured and Low-Income

Racial/Ethnic Disparities

Safety Net Providers

Community Health Centers

Hospitals

Physicians

Insured People

Quality & Care Delivery

Health Care Markets

Insurance Coverage & Costs

Access to Care

Uninsured and Low-Income

Racial/Ethnic Disparities

Safety Net Providers

Community Health Centers

Hospitals

Physicians

Insured People

Quality & Care Delivery

Health Care Markets

Issue Briefs

Data Bulletins

Research Briefs

Policy Analyses

Community Reports

Journal Articles

Other Publications

Surveys

Site Visits

Design and Methods

Data Files

|

Rapid Population Growth Attracts National Firms

Phoenix, Arizona

Community Report No. 04

Winter 2001

Debra A. Draper, Linda R. Brewster, Lawrence D. Brown, Carolyn A. Watts, Laurie E. Felland, Jon B. Christianson, Jeffrey Stoddard, Michael H. Park

n September 2000, a team of

researchers visited Phoenix, Ariz., to

study that community’s health system,

how it is changing and the effects

of those changes on consumers. The

Center for Studying Health System

Change (HSC), as part of the

Community Tracking Study, interviewed

more than 85 leaders in the

health care market. Phoenix is one of

12 communities tracked by HSC

every two years through site visits and

surveys. Individual community

reports are published for each round

of site visits. The first two site visits to

Phoenix, in 1996 and 1998, provided

baseline and initial trend information

against which changes are

tracked. The Phoenix market encompasses

Maricopa and Pinal counties. n September 2000, a team of

researchers visited Phoenix, Ariz., to

study that community’s health system,

how it is changing and the effects

of those changes on consumers. The

Center for Studying Health System

Change (HSC), as part of the

Community Tracking Study, interviewed

more than 85 leaders in the

health care market. Phoenix is one of

12 communities tracked by HSC

every two years through site visits and

surveys. Individual community

reports are published for each round

of site visits. The first two site visits to

Phoenix, in 1996 and 1998, provided

baseline and initial trend information

against which changes are

tracked. The Phoenix market encompasses

Maricopa and Pinal counties.

With the addition of 100,000 people a year, Phoenix

continues to grow rapidly, making its health care market

attractive to national firms. A series of hospital acquisitions

since 1998 has left these firms in control of the

majority of the area’s hospital capacity. National firms are

also dominant in the health plan market, although a new

focus on profitability is leading some to eliminate unprofitable

lines of business, including Medicare+Choice. A

national hospital management company is credited with

helping to stabilize the community’s major safety-net

provider, but concerns remain about the area’s capacity to

care for the uninsured.

Against this backdrop, key developments in Phoenix

since 1998 include:

- Hospitals began to increase their leverage with health

plans, but financial pressures mounted as some physicians

shifted focus from hospitals to independent

specialty facilities.

- Changes to plans’ Medicare+Choice products have left

seniors with fewer choices and higher costs.

- Arizona citizens used ballot initiatives to secure funding

to care for the uninsured.

Hospital Systems Consolidate and Gain Leverage

ooming population growth has led many Phoenix hospitals to pursue affiliations

with national systems to obtain capital necessary to respond to increasing demand.

As a result of acquisitions, the Phoenix market has 10 hospital systems (excluding

specialty hospitals)- down from 13 systems two years ago. The most significant

acquisition was a merger between Samaritan Health System, the area’s largest provider

system, and the national Lutheran Health Network to form BannerHealth Arizona-

a five-hospital system that accounts for the largest share of hospital capacity

in Phoenix.

Other national firms active in the

market are Catholic Healthcare West,

Vanguard Health Systems, Iasis Healthcare,

Triad Hospitals and Quorum Health

Resources. National firms now control 70

percent of the Phoenix community’s

hospital capacity, a figure that may soon

increase if Vanguard acquires PMH

Resources, owner of Phoenix Memorial

Hospital, as some observers speculate.

Several hospitals have turned to

their new partners for capital to fund

facility upgrades and new competitive

ventures. BannerHealth Arizona, for

example, has initiated an $88 million

project to expand capacity at Desert

Samaritan and Thunderbird Samaritan

hospitals, and it recently completed construction

of a 60-bed heart hospital on

the campus of Mesa Lutheran Hospital

in a joint venture with local cardiologists.

Likewise, Catholic Healthcare West is

undertaking $21 million in renovations

to expand capacity at Chandler Regional

Hospital in the East Valley and plans to

expand pediatric and neonatology services

at St. Joseph’s Hospital downtown.

However, the shortage of nurses and other

health care professionals may limit hospitals’

ability to bring new capacity on line.

Since 1998, Phoenix hospitals have

made strategic moves to gain footholds in

specific areas of the geographically broad

market to ensure their indispensability to

health plan networks. As one hospital

executive put it, "Geography is destiny"

in the Phoenix market. Most hospital systems

have focused their strategic efforts

on securing strongholds in key geographic

submarkets. Catholic Healthcare West, for

example, strengthened its market position

with the acquisition of Chandler Regional

Hospital, which gave it a foothold in the

rapidly growing East Valley. Newly consolidated

BannerHealth Arizona has a

strong market position because it offers

the broadest geographic coverage in

the market.

Health plans report that hospitals’

virtual monopolies in certain geographic

areas give hospitals a significant advantage

in negotiations, resulting in more favorable

contract terms and higher payment

rates for hospitals. In addition, plans contend

that BannerHealth Arizona has

begun to leverage its strong market position

and name-brand recognition to

secure higher payment rates and better

contract terms, limiting health plans’

ability to hold down costs. ooming population growth has led many Phoenix hospitals to pursue affiliations

with national systems to obtain capital necessary to respond to increasing demand.

As a result of acquisitions, the Phoenix market has 10 hospital systems (excluding

specialty hospitals)- down from 13 systems two years ago. The most significant

acquisition was a merger between Samaritan Health System, the area’s largest provider

system, and the national Lutheran Health Network to form BannerHealth Arizona-

a five-hospital system that accounts for the largest share of hospital capacity

in Phoenix.

Other national firms active in the

market are Catholic Healthcare West,

Vanguard Health Systems, Iasis Healthcare,

Triad Hospitals and Quorum Health

Resources. National firms now control 70

percent of the Phoenix community’s

hospital capacity, a figure that may soon

increase if Vanguard acquires PMH

Resources, owner of Phoenix Memorial

Hospital, as some observers speculate.

Several hospitals have turned to

their new partners for capital to fund

facility upgrades and new competitive

ventures. BannerHealth Arizona, for

example, has initiated an $88 million

project to expand capacity at Desert

Samaritan and Thunderbird Samaritan

hospitals, and it recently completed construction

of a 60-bed heart hospital on

the campus of Mesa Lutheran Hospital

in a joint venture with local cardiologists.

Likewise, Catholic Healthcare West is

undertaking $21 million in renovations

to expand capacity at Chandler Regional

Hospital in the East Valley and plans to

expand pediatric and neonatology services

at St. Joseph’s Hospital downtown.

However, the shortage of nurses and other

health care professionals may limit hospitals’

ability to bring new capacity on line.

Since 1998, Phoenix hospitals have

made strategic moves to gain footholds in

specific areas of the geographically broad

market to ensure their indispensability to

health plan networks. As one hospital

executive put it, "Geography is destiny"

in the Phoenix market. Most hospital systems

have focused their strategic efforts

on securing strongholds in key geographic

submarkets. Catholic Healthcare West, for

example, strengthened its market position

with the acquisition of Chandler Regional

Hospital, which gave it a foothold in the

rapidly growing East Valley. Newly consolidated

BannerHealth Arizona has a

strong market position because it offers

the broadest geographic coverage in

the market.

Health plans report that hospitals’

virtual monopolies in certain geographic

areas give hospitals a significant advantage

in negotiations, resulting in more favorable

contract terms and higher payment

rates for hospitals. In addition, plans contend

that BannerHealth Arizona has

begun to leverage its strong market position

and name-brand recognition to

secure higher payment rates and better

contract terms, limiting health plans’

ability to hold down costs.

Physicians Shift Focus to Specialty Facilities

hysicians’ discontent with the local

health care system has reached new

heights over the past two years, and

physicians are aggressively pursuing

strategies to improve their financial

situations. Perhaps most significant,

some specialists have cut back on their

affiliations with traditional hospitals,

choosing instead to devote more time

to their own ambulatory treatment and

surgery centers or specialty hospitals in

which they have equity interests. These

facilities offer the potential for physicians

to generate higher incomes by sharing in

facility profits. The drawback is that the

growth of specialty facilities threatens

traditional hospitals with the loss of profitable

services and, as a result, limits their

ability to sustain cross-subsidies essential

for financing less profitable lines of business.

Moreover, to avoid seeing uninsured

patients for whom they will not be reimbursed,

some specialists have stopped

providing emergency room coverage

in Phoenix. Hospitals report that it is

increasingly difficult to provide on-call

coverage for certain specialties, and they

say that some specialists are banding

together in "cartel-like" arrangements

to demand above-market reimbursement

from hospitals for their services. Specialists’

decisions not to provide emergency room

coverage may have gained impetus from

regulations under the federal Emergency

Medical Treatment and Labor Act, which

imposes hefty fines if a physician or hospital

inappropriately transfers a medically

unstable patient to another facility for any

reason, including inability to pay.

Relationships between physicians

and health plans in Phoenix have also

become very contentious in the past two

years. On the heels of financial difficulties

that many attribute largely to managed

care, physicians increasingly are refusing

to enter into risk contracts with health

plans, and health plans are reverting to

fee-for-service payment. Meanwhile,

nearly every attempt at building organizations

to allow physicians to accept risk

has failed, leaving dim prospects for risk

contracting in the future. hysicians’ discontent with the local

health care system has reached new

heights over the past two years, and

physicians are aggressively pursuing

strategies to improve their financial

situations. Perhaps most significant,

some specialists have cut back on their

affiliations with traditional hospitals,

choosing instead to devote more time

to their own ambulatory treatment and

surgery centers or specialty hospitals in

which they have equity interests. These

facilities offer the potential for physicians

to generate higher incomes by sharing in

facility profits. The drawback is that the

growth of specialty facilities threatens

traditional hospitals with the loss of profitable

services and, as a result, limits their

ability to sustain cross-subsidies essential

for financing less profitable lines of business.

Moreover, to avoid seeing uninsured

patients for whom they will not be reimbursed,

some specialists have stopped

providing emergency room coverage

in Phoenix. Hospitals report that it is

increasingly difficult to provide on-call

coverage for certain specialties, and they

say that some specialists are banding

together in "cartel-like" arrangements

to demand above-market reimbursement

from hospitals for their services. Specialists’

decisions not to provide emergency room

coverage may have gained impetus from

regulations under the federal Emergency

Medical Treatment and Labor Act, which

imposes hefty fines if a physician or hospital

inappropriately transfers a medically

unstable patient to another facility for any

reason, including inability to pay.

Relationships between physicians

and health plans in Phoenix have also

become very contentious in the past two

years. On the heels of financial difficulties

that many attribute largely to managed

care, physicians increasingly are refusing

to enter into risk contracts with health

plans, and health plans are reverting to

fee-for-service payment. Meanwhile,

nearly every attempt at building organizations

to allow physicians to accept risk

has failed, leaving dim prospects for risk

contracting in the future.

Health Plans Seek to Regain Profitability

ealth plans’ profitability has eroded

considerably in Phoenix since 1998,

a situation that has led to rising premiums

and instability in the health plan

market. Of the 10 commercial health

maintenance organizations (HMOs)

currently operating in Phoenix, only

two-Cigna and PacifiCare-are reportedly

profitable. Health plans in Phoenix

once relied on a strategy of increasing

their market share by keeping premiums

low. Like other health plans nationally,

however, many of them have concluded

that this strategy is unsustainable and

are increasing premiums and eliminating

unprofitable or marginal lines of business

to improve their financial condition.

Individuals with coverage from large

employers appear to have been largely

sheltered from health plans’ premium

increases. In the tight labor market

(currently under 3 percent unemployment),

most large firms have sought to

absorb the added costs or make only

minor changes to benefit structures,

viewing increased out-of-pocket costs

for their employees as a last resort.

Observers note, however, that small

employers-which account for the vast

majority of Phoenix area workplaces-

have been more likely to change health

plans to get a better price or to drop

coverage for employees altogether if they

are unable to find affordable rates. This

trend has significant implications in a

market where more than 25 percent of

the population already goes without

health insurance.

Health plans’ recent financial problems

have prompted the Arizona

Department of Insurance (DOI) to

place two plans, UnitedHealthcare and

Intergroup, on a "watch" status to monitor

their performance more closely. DOI’s

actions are attributed to criticism the

agency received for not adequately monitoring

the financial condition of Premier

Healthcare, a small provider-sponsored

HMO that became insolvent and went

into receivership in November 1999.

Problems with plans failing to pay

providers on time have also prompted

increased scrutiny by DOI, resulting in

fines for some plans.

DOI’s recent interventions reflect

an increasingly regulated health plan

environment that has emerged in Arizona

and nationally. In 1999, the Arizona legislature

enacted an HMO reform law giving

patients various rights to appeal their

health plan’s decisions, including the

right to sue their health plan. The list

of legislatively mandated health plan

benefits, which continues to grow, now

includes cancer clinical trials and chiropractic

services. Under a new state law

that takes effect this year, Arizona’s

bifurcated system of managed care

oversight will be eliminated, and the

health delivery and quality monitoring

responsibilities of the Department of

Health Services will be transferred to DOI.

Health plan respondents claim that Arizona’s new managed care regulations are

increasing costs, resulting in higher premiums for consumers. Other respondents

assert, however, that the regulations are needed to ensure that patient care and

provider payment are protected adequately in a managed care environment. ealth plans’ profitability has eroded

considerably in Phoenix since 1998,

a situation that has led to rising premiums

and instability in the health plan

market. Of the 10 commercial health

maintenance organizations (HMOs)

currently operating in Phoenix, only

two-Cigna and PacifiCare-are reportedly

profitable. Health plans in Phoenix

once relied on a strategy of increasing

their market share by keeping premiums

low. Like other health plans nationally,

however, many of them have concluded

that this strategy is unsustainable and

are increasing premiums and eliminating

unprofitable or marginal lines of business

to improve their financial condition.

Individuals with coverage from large

employers appear to have been largely

sheltered from health plans’ premium

increases. In the tight labor market

(currently under 3 percent unemployment),

most large firms have sought to

absorb the added costs or make only

minor changes to benefit structures,

viewing increased out-of-pocket costs

for their employees as a last resort.

Observers note, however, that small

employers-which account for the vast

majority of Phoenix area workplaces-

have been more likely to change health

plans to get a better price or to drop

coverage for employees altogether if they

are unable to find affordable rates. This

trend has significant implications in a

market where more than 25 percent of

the population already goes without

health insurance.

Health plans’ recent financial problems

have prompted the Arizona

Department of Insurance (DOI) to

place two plans, UnitedHealthcare and

Intergroup, on a "watch" status to monitor

their performance more closely. DOI’s

actions are attributed to criticism the

agency received for not adequately monitoring

the financial condition of Premier

Healthcare, a small provider-sponsored

HMO that became insolvent and went

into receivership in November 1999.

Problems with plans failing to pay

providers on time have also prompted

increased scrutiny by DOI, resulting in

fines for some plans.

DOI’s recent interventions reflect

an increasingly regulated health plan

environment that has emerged in Arizona

and nationally. In 1999, the Arizona legislature

enacted an HMO reform law giving

patients various rights to appeal their

health plan’s decisions, including the

right to sue their health plan. The list

of legislatively mandated health plan

benefits, which continues to grow, now

includes cancer clinical trials and chiropractic

services. Under a new state law

that takes effect this year, Arizona’s

bifurcated system of managed care

oversight will be eliminated, and the

health delivery and quality monitoring

responsibilities of the Department of

Health Services will be transferred to DOI.

Health plan respondents claim that Arizona’s new managed care regulations are

increasing costs, resulting in higher premiums for consumers. Other respondents

assert, however, that the regulations are needed to ensure that patient care and

provider payment are protected adequately in a managed care environment.

Seniors Face Fewer Choices and Higher Costs

hoenix is one of the strongest Medicare

managed care markets in the country.

Zero dollar premiums and generous

benefit packages, including pharmaceutical

coverage, have attracted 168,000 local

Medicare beneficiaries (42 percent) to

Medicare+Choice HMOs. Recently, however,

the struggle by Phoenix health plans

to restore profitability has led some health

plans to withdraw from Medicare+Choice.

Other plans have instituted premiums

and/or reduced benefits in their Medicare

HMOs, leaving seniors with fewer choices

and higher out-of-pocket costs.

Since 1998, two health plans

have dropped out of the Phoenix

Medicare+Choice market. The withdrawal

of UnitedHealthcare and Blue

Cross Blue Shield of Arizona affected

20,000 Medicare beneficiaries, most of

whom are thought to have enrolled in

other HMOs. Though seven other

plans are expected to participate in the

Medicare+Choice market in 2001, these

plans say that low payment rates, coupled

with Balanced Budget Act imposed rate

ceilings that are significantly below medical

cost trends, limit their ability to make

long-term participation commitments.

Furthermore, health plans that

remain in the Phoenix Medicare+Choice

market are requiring seniors to contribute

more to the cost of care. Seniors who

previously paid no premiums in most

Medicare+Choice plans now face monthly

premiums of $25 or more, higher copayments

and more restrictive caps on

prescription drug coverage. Despite these

changes, demand for Medicare+Choice

plans in Phoenix remains strong, especially

among the area’s many young and

healthy retirees and individuals who want

the prescription drug benefit. Health

plans contend that they have no recourse

other than to increase beneficiary contributions

and reduce benefits if they are

to continue to participate in the

Medicare+Choice program and

remain financially sound.

Some health plans are considering

alternative Medicare products such as

preferred provider organizations (PPOs),

but so far no new managed care products

have been introduced into the market.

Recently, Sterling Life Insurance Company

began marketing a Medicare private fee-for-

service product in Phoenix. It is too

soon to determine what, if any, impact

such fee-for-service products will have

on the market. hoenix is one of the strongest Medicare

managed care markets in the country.

Zero dollar premiums and generous

benefit packages, including pharmaceutical

coverage, have attracted 168,000 local

Medicare beneficiaries (42 percent) to

Medicare+Choice HMOs. Recently, however,

the struggle by Phoenix health plans

to restore profitability has led some health

plans to withdraw from Medicare+Choice.

Other plans have instituted premiums

and/or reduced benefits in their Medicare

HMOs, leaving seniors with fewer choices

and higher out-of-pocket costs.

Since 1998, two health plans

have dropped out of the Phoenix

Medicare+Choice market. The withdrawal

of UnitedHealthcare and Blue

Cross Blue Shield of Arizona affected

20,000 Medicare beneficiaries, most of

whom are thought to have enrolled in

other HMOs. Though seven other

plans are expected to participate in the

Medicare+Choice market in 2001, these

plans say that low payment rates, coupled

with Balanced Budget Act imposed rate

ceilings that are significantly below medical

cost trends, limit their ability to make

long-term participation commitments.

Furthermore, health plans that

remain in the Phoenix Medicare+Choice

market are requiring seniors to contribute

more to the cost of care. Seniors who

previously paid no premiums in most

Medicare+Choice plans now face monthly

premiums of $25 or more, higher copayments

and more restrictive caps on

prescription drug coverage. Despite these

changes, demand for Medicare+Choice

plans in Phoenix remains strong, especially

among the area’s many young and

healthy retirees and individuals who want

the prescription drug benefit. Health

plans contend that they have no recourse

other than to increase beneficiary contributions

and reduce benefits if they are

to continue to participate in the

Medicare+Choice program and

remain financially sound.

Some health plans are considering

alternative Medicare products such as

preferred provider organizations (PPOs),

but so far no new managed care products

have been introduced into the market.

Recently, Sterling Life Insurance Company

began marketing a Medicare private fee-for-

service product in Phoenix. It is too

soon to determine what, if any, impact

such fee-for-service products will have

on the market.

Arizona Citizens Press for Aid for Large Uninsured Population

he Phoenix area has one of the highest

rates of uninsurance in the country, with

more than one-quarter of the population

lacking coverage. Only 60 percent of

working adults and their dependents

receive health insurance through their

employers, and the preponderance of

low-wage jobs in the local employment

sector makes it likely that many people

cannot afford to purchase insurance on

their own. Federal welfare reform legislation

enacted in 1996 has contributed to

the insurance coverage problem, because

reportedly large numbers of former

welfare recipients who remain eligible

for Medicaid have not reenrolled. Arizona’s

State Child Health Insurance Program

(SCHIP), KidsCare, was implemented in

November 1998, and roughly 80,000 children

have gained coverage as a result of

KidsCare outreach efforts-half through

Medicaid and half through SCHIP. State

officials had originally hoped to enroll

60,000 children in KidsCare alone and

are now stepping up efforts to reach

this population.

Historically, Arizona’s political

climate has not been supportive of

state-sponsored initiatives to provide

funding for the uninsured, but in recent

years, Arizona citizens have used state

ballot initiatives to force the hand of the

legislature to address the insurance

coverage problem. An Arizona state ballot

initiative passed in 1994 created a tobacco

tax, with 70 percent of the revenues

dedicated to subsidizing health care for

the uninsured. Currently, these tobacco

tax revenues are the only source of funding

that can be used to provide care for

undocumented immigrants in Phoenix

and elsewhere in the state. With health

care costs continuing to escalate, however,

there are concerns that tobacco tax

revenues will not keep pace with the

health care needs of the large number

of uninsured persons.

In November 2000, Arizona citizens

passed two competing state ballot initiatives-

Proposition 200 and Proposition

204-that earmark the state’s $3.1 billion

tobacco settlement monies to expand

coverage to the population without health

insurance. Proposition 204 had the most

votes and was recently approved by federal

officials. The new funding will expand

Medicaid eligibility by raising the income

ceiling for eligibility to 100 percent of the

federal poverty level, extending coverage

to 130,000-180,000 Arizona residents

who lack health insurance-a 30 percent

increase over current Medicaid enrollment.

Despite the pressures of a large

uninsured population, the Phoenix

safety net has been relatively stable, but

that stability may now be in jeopardy.

Four downtown hospitals-the county-owned

Maricopa Integrated Health

System (MIHS), Good Samaritan, St.

Joseph’s and Phoenix Memorial-

provide care for the uninsured, as

does an extensive network of community

health clinics (CHCs) in Phoenix.

Market observers report that uninsured

individuals have reasonably good access

to primary care through the CHCs,

either by appointment or on a walk-in

basis. Securing specialty and inpatient

care through the CHCs, however, is

reportedly more difficult. To link

uninsured individuals with specialty

or inpatient care, CHCs rely largely

on relationships they have established

with providers in the community.

Some respondents express concern

that access to care for the uninsured

is deteriorating at MIHS. In 1994,

following substantial losses that threatened

its continued existence, MIHS

entered into a management agreement

with the for-profit hospital management

company, Quorum Health Resources.

Quorum has been successful in helping

to restore profitability to the county-owned

system, which reportedly now

has a surplus in excess of $18 million.

Although MIHS’s improved financial

condition may help to stabilize the

system as a key provider of care for

the uninsured, some respondents

speculate that its financial turnaround

has been the result of a decline in the

amount of uncompensated care the

system provides.

Consistent with these reports, other hospitals have noted significant increases

in emergency room use by uninsured persons. Some observers fear that this situation

will worsen under MIHS’s plan to shed its county hospital image by obtaining state

authorization to form a hospital district. This change will enable MIHS to compete

for a broader base of business, but some observers worry that it may also undermine

MIHS’s commitment to serve the uninsured. he Phoenix area has one of the highest

rates of uninsurance in the country, with

more than one-quarter of the population

lacking coverage. Only 60 percent of

working adults and their dependents

receive health insurance through their

employers, and the preponderance of

low-wage jobs in the local employment

sector makes it likely that many people

cannot afford to purchase insurance on

their own. Federal welfare reform legislation

enacted in 1996 has contributed to

the insurance coverage problem, because

reportedly large numbers of former

welfare recipients who remain eligible

for Medicaid have not reenrolled. Arizona’s

State Child Health Insurance Program

(SCHIP), KidsCare, was implemented in

November 1998, and roughly 80,000 children

have gained coverage as a result of

KidsCare outreach efforts-half through

Medicaid and half through SCHIP. State

officials had originally hoped to enroll

60,000 children in KidsCare alone and

are now stepping up efforts to reach

this population.

Historically, Arizona’s political

climate has not been supportive of

state-sponsored initiatives to provide

funding for the uninsured, but in recent

years, Arizona citizens have used state

ballot initiatives to force the hand of the

legislature to address the insurance

coverage problem. An Arizona state ballot

initiative passed in 1994 created a tobacco

tax, with 70 percent of the revenues

dedicated to subsidizing health care for

the uninsured. Currently, these tobacco

tax revenues are the only source of funding

that can be used to provide care for

undocumented immigrants in Phoenix

and elsewhere in the state. With health

care costs continuing to escalate, however,

there are concerns that tobacco tax

revenues will not keep pace with the

health care needs of the large number

of uninsured persons.

In November 2000, Arizona citizens

passed two competing state ballot initiatives-

Proposition 200 and Proposition

204-that earmark the state’s $3.1 billion

tobacco settlement monies to expand

coverage to the population without health

insurance. Proposition 204 had the most

votes and was recently approved by federal

officials. The new funding will expand

Medicaid eligibility by raising the income

ceiling for eligibility to 100 percent of the

federal poverty level, extending coverage

to 130,000-180,000 Arizona residents

who lack health insurance-a 30 percent

increase over current Medicaid enrollment.

Despite the pressures of a large

uninsured population, the Phoenix

safety net has been relatively stable, but

that stability may now be in jeopardy.

Four downtown hospitals-the county-owned

Maricopa Integrated Health

System (MIHS), Good Samaritan, St.

Joseph’s and Phoenix Memorial-

provide care for the uninsured, as

does an extensive network of community

health clinics (CHCs) in Phoenix.

Market observers report that uninsured

individuals have reasonably good access

to primary care through the CHCs,

either by appointment or on a walk-in

basis. Securing specialty and inpatient

care through the CHCs, however, is

reportedly more difficult. To link

uninsured individuals with specialty

or inpatient care, CHCs rely largely

on relationships they have established

with providers in the community.

Some respondents express concern

that access to care for the uninsured

is deteriorating at MIHS. In 1994,

following substantial losses that threatened

its continued existence, MIHS

entered into a management agreement

with the for-profit hospital management

company, Quorum Health Resources.

Quorum has been successful in helping

to restore profitability to the county-owned

system, which reportedly now

has a surplus in excess of $18 million.

Although MIHS’s improved financial

condition may help to stabilize the

system as a key provider of care for

the uninsured, some respondents

speculate that its financial turnaround

has been the result of a decline in the

amount of uncompensated care the

system provides.

Consistent with these reports, other hospitals have noted significant increases

in emergency room use by uninsured persons. Some observers fear that this situation

will worsen under MIHS’s plan to shed its county hospital image by obtaining state

authorization to form a hospital district. This change will enable MIHS to compete

for a broader base of business, but some observers worry that it may also undermine

MIHS’s commitment to serve the uninsured.

Issues to Track

apid population growth continues to shape the Phoenix health

care market, attracting national firms and helping them to attain a dominant position

among both hospitals and health plans. Consolidation and new partnerships have

helped to strengthen hospitals’ bargaining power relative to health plans during

the past two years, but shifts by some physicians from providing services through

traditional hospitals in favor of their own specialty facilities are adding to

hospitals’ financial pressures and disrupting coverage arrangements. Meanwhile,

health plans have been struggling to regain financial stability. The result has

been higher premiums, reduced benefits and fewer plans participating in Medicare+Choice.

Large numbers of Phoenix residents remain uninsured, and respondents worry that

further changes in the county- owned hospital system threaten to weaken the safety

net in the future.

As the Phoenix health care market continues to evolve, the following issues are

important to track: apid population growth continues to shape the Phoenix health

care market, attracting national firms and helping them to attain a dominant position

among both hospitals and health plans. Consolidation and new partnerships have

helped to strengthen hospitals’ bargaining power relative to health plans during

the past two years, but shifts by some physicians from providing services through

traditional hospitals in favor of their own specialty facilities are adding to

hospitals’ financial pressures and disrupting coverage arrangements. Meanwhile,

health plans have been struggling to regain financial stability. The result has

been higher premiums, reduced benefits and fewer plans participating in Medicare+Choice.

Large numbers of Phoenix residents remain uninsured, and respondents worry that

further changes in the county- owned hospital system threaten to weaken the safety

net in the future.

As the Phoenix health care market continues to evolve, the following issues are

important to track:

- What effects will contrary pressures- hospitals’ increasing negotiating

leverage with health plans and physicians shifting to specialty facilities-have

on hospital prices and overall health care costs?

- As health plans attempt to restore profitability by increasing premiums,

how will the low-wage market respond? Will employers shift the increased costs

to their employees? Will they drop coverage? Or will purchasers push for more

tightly managed products?

- What impact will changes by health plans in their Medicare products have

on the Phoenix market? Will Phoenix seniors see improved choice of plans,

lower costs and/or expanded benefits? Will seniors return to traditional fee-for-

service coverage?

- How will increased funding allocated under recent ballot initiatives affect

insurance coverage? Will the local safety net continue to have sufficient

capacity to serve the remaining uninsured?

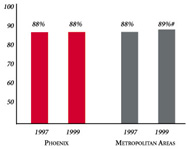

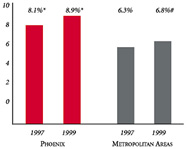

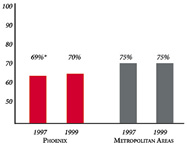

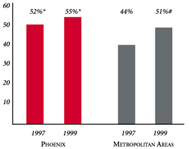

Phoenix’s Experience with the Local Health System, 1997 and 1999

Background and Observations

| Phoenix Demographics |

| Phoenix |

Metropolitan areas above 200,000 population |

Population, July 1, 19991

3,013,696 |

| Population Change, 1990-19992

|

| 35% |

8.6% |

| Median Income3 |

| $29,135 |

$27,843 |

| Persons Living in Poverty3 |

| 14% |

14% |

| Persons Age 65 or Older3 |

| 13% |

11% |

Sources:

1. US Bureau of Census, 1999 Community Population Estimates

2. US Bureau of Census, 1990 & 1999 Community Population Estimates

3. Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1998-1999 |

| Health Insurance Status |

| Phoenix |

Metropolitan areas above 200,000 population |

| Persons under Age 65 with No Health Insurance1 |

| 17% |

15% |

| Children under Age 18 with No Health Insurance1

|

| 16% |

11% |

| Employees Working for Private Firms that

Offer Coverage2 |

| 86% |

84% |

| Average Monthly Premium for Self-Only Coverage

under Employer-Sponsored Insurance2 |

| $151 |

$181 |

Sources:

1. Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1998-1999

2. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Employer Health Insurance Survey, 1997 |

| Health System Characteristics |

| Phoenix |

Metropolitan areas above 200,000 population |

| Staffed Hospital Beds per 1,000 Population1

|

| 2.2 |

2.8 |

| Physicians per 1,000 Population2

|

| 1.7 |

2.3 |

| HMO Penetration, 19973 |

| 34% |

32% |

| HMO Penetration, 19994 |

| 34% |

36% |

Sources:

1. American Hospital Association, 1998

2. Area Resource File, 1998 (includes nonfederal, patient care physicians,

except radiologists, pathologists and anesthesiologists)

3. InterStudy Competitive Edge 8.1

4. InterStudy Competitive Edge 10.1 |

The Community Tracking Study, the major effort of the Center for Studying Health

System Change (HSC), tracks changes in the health system in 60 sites that are

representative of the nation. Every two years, HSC conducts surveys in all 60

communities and site visits in 12 communities. The Community Report series documents

the findings from the third round of site visits. Analyses based on site visit

and survey data from the Community Tracking Study are published by HSC in Issue

Briefs, Data Bulletins and peer-reviewed journals. These publications are

available at www.hschange.org.

Authors of the Phoenix Community Report:

Debra A. Draper, Mathematica Policy Research, Inc.

Linda R. Brewster, HSC

Lawrence D. Brown, Columbia University

Carolyn A. Watts, University of Washington

Laurie E. Felland, HSC

Jon B. Christianson, University of Minnesota

Jeffrey Stoddard, HSC

Michael Park, HSC

Community Reports are published by HSC:

President: Paul B. Ginsburg

Director of Site Visits: Cara S. Lesser

Director of Public Affairs: Ann C. Greiner

Editor: The Stein Group

|