Tax Credits and Purchasing Pools: Will This Marriage Work?

Issue Brief No. 36

April 2001

Sally Trude, Paul B. Ginsburg

![]() ipartisan interest is growing in Congress for using federal tax credits to help low-income

families buy health insurance. Regardless of the approach taken, tax credit

policies must address risk selection issues to ensure coverage for the chronically ill.

Proposals that link tax credits to purchasing pools would avoid risk selection by

grouping risks similar to the way large employers do. Voluntary purchasing pools

have had only limited success, however. This Issue Brief discusses linking tax credits

to purchasing pools. It uses information from the Center for Studying Health

System Change’s (HSC) site visits to 12 communities as well as other research to

assess the role of purchasing pools nationwide and the key issues and implications

of linking tax credits and pools.

ipartisan interest is growing in Congress for using federal tax credits to help low-income

families buy health insurance. Regardless of the approach taken, tax credit

policies must address risk selection issues to ensure coverage for the chronically ill.

Proposals that link tax credits to purchasing pools would avoid risk selection by

grouping risks similar to the way large employers do. Voluntary purchasing pools

have had only limited success, however. This Issue Brief discusses linking tax credits

to purchasing pools. It uses information from the Center for Studying Health

System Change’s (HSC) site visits to 12 communities as well as other research to

assess the role of purchasing pools nationwide and the key issues and implications

of linking tax credits and pools.

Tax Credits for Health Insurance

![]() ax credits have recently gained

broad support as a way to help

low-income families afford health

insurance. One recent bipartisan proposal

from Congress would provide a

refundable tax credit of up to $2,500 a

year for uninsured families that could

use the subsidy to purchase insurance

through the individual market

or their employer.1

Sponsors estimate

that this proposal would gain coverage

for about one-quarter of the estimated

43 million uninsured Americans.

ax credits have recently gained

broad support as a way to help

low-income families afford health

insurance. One recent bipartisan proposal

from Congress would provide a

refundable tax credit of up to $2,500 a

year for uninsured families that could

use the subsidy to purchase insurance

through the individual market

or their employer.1

Sponsors estimate

that this proposal would gain coverage

for about one-quarter of the estimated

43 million uninsured Americans.

It may be difficult, however, for tax credit recipients to afford individual health insurance. In the individual market, there are fewer insurers to choose from, consumers have much less bargaining power and overhead costs are much higher. Moreover, in most states, individual insurance is fully risk rated, so older and sicker people pay much higher than average rates. Also, insurers deny coverage or preclude coverage for preexisting conditions. 2 Therefore, a tax credit may not be enough for the chronically ill or those with a previous illness to obtain or afford health insurance. 3, 4

Efforts to reform the individual market could be problematic because in a regulated market, competition tends to focus on risk avoidance. If reforms constrain insurers’ ability to underwrite based on individual health status or health risk, then they will seek other ways to avoid higher risks, such as designing benefits to appeal to healthier people.

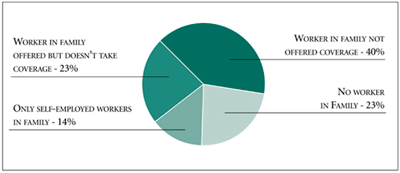

For low-wage workers in companies that offer insurance, the tax credit will help pay their share of the premium. Nearly one-quarter of the uninsured do not purchase health insurance offered by their employer, based on findings from the HSC 1999 Community Tracking Study (CTS) Household Survey (see Figure). Workers who decline employer-sponsored insurance coverage are more likely to be low-wage workers, which suggests that they decline coverage for financial reasons. 5, 6

To avoid the problems of the individual market, some tax credit proposals tie the subsidy to public programs or the workplace. Employer-based approaches are intended for the 63 percent of the uninsured who have an employed worker in their family. They also reflect worker preferences: 56 percent of employees would prefer to obtain health insurance through their employer, compared with 20 percent who would prefer to buy it on their own. 7

In addition, employer-based policies can target small firms, where only 37 percent of workers are offered and choose to take up insurance, compared with 68 percent of workers in large companies, according to 1999 CTS Household Survey findings. Policies focusing only on small employers, however, reflect individual rather than family income. Such policies also ignore low-income uninsured workers in large companies.

| Figure Percent of Uninsured People by Availability of Employer-Sponsored Coverage  Source: Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1999 |

Linking Tax Credits to Purchasing Pools

![]() nother option is to direct the tax credits

to low-income families and require that

they be used only with a limited number

of authorized group-purchasing entities.

8

nother option is to direct the tax credits

to low-income families and require that

they be used only with a limited number

of authorized group-purchasing entities.

8

These purchasing pools will keep all those subsidized by the tax credits in a single risk pool and achieve some of the administrative efficiencies and bargaining clout of large employers. Large employers pool risks across individuals-the sickest to the healthiest-so that everyone pays the same premium for a given plan, regardless of their health status. If purchasing pools use community rating (where everyone pays the same, regardless of his or her risk), they will ensure that the chronically ill can obtain and afford insurance coverage. The purchasing pools will standardize benefits, which would prevent health plans from attracting better risks through benefit options designed to appeal to healthy individuals.

In addition, the purchasing pools will carry out many of the administrative functions of a large employers’ benefit manager, such as coordinating enrollment, negotiating with health plans to develop a choice of offerings and developing comparison charts to help consumers make benefit selections. They also will collect small firms’ payroll deductions, saving health plans the cost of collecting premiums from individuals.

Requiring the use of authorized purchasing pools is likely to improve their success by preventing lower-risk people from buying cheaper insurance outside the pool. For example, if a purchasing pool opens its membership to high-risk clients and uses community rating, the pool will attract higher risks and drive up premiums, making it uncompetitive with insurers offering coverage outside the pool. On the other hand, while a pool that protects against adverse selection through restrictive membership standards avoids this problem, it will not help accomplish the social goal of extending insurance to sicker people.

Start-up funds might be necessary to ensure that private purchasing pools are available everywhere. Currently, the availability of purchasing pools varies considerably by area. Some markets, such as Cleveland, have a strong local purchasing pool, but no statewide entity. In one-third of HSC’s 12 nationally representative communities (Greenville, Little Rock, Miami and Northern New Jersey), health market leaders could not identify an organization that currently pools risk. Although Miami had a purchasing cooperative, the Florida Community Health Purchasing Alliance (CHPA) is disbanding and no longer operates in the Miami area.

Furthermore, many difficult policy issues have to be resolved to link tax credits to purchasing pools. These include how the pools are selected, allowable administration fees, who determines individuals’ eligibility and who adjudicates grievances. More general issues to resolve include the amount of flexibility the purchasing pool will be allowed in establishing benefit structures, the extent of state and federal oversight and who bears any potential liability. Policy makers’ support for linking tax credits to purchasing pools will depend on resolution of all these issues.

Lessons from the Past

![]() s voluntary entities, purchasing pools

have not been shown either to expand

coverage or reduce the cost of premiums.

9

Research using the 1997 Robert Wood

Johnson Foundation Employer Survey, a

component of the CTS, found that purchasing

pools had not increased the number

of individuals with coverage or made

insurance more affordable.

10

Nor have

they gained substantial market share.

For example, two statewide purchasing

cooperatives in California, each covering

about 150,000 workers, capture only 4

percent of the potential market.

s voluntary entities, purchasing pools

have not been shown either to expand

coverage or reduce the cost of premiums.

9

Research using the 1997 Robert Wood

Johnson Foundation Employer Survey, a

component of the CTS, found that purchasing

pools had not increased the number

of individuals with coverage or made

insurance more affordable.

10

Nor have

they gained substantial market share.

For example, two statewide purchasing

cooperatives in California, each covering

about 150,000 workers, capture only 4

percent of the potential market.

Some purchasing pools have failed to gain substantial membership because of resistance from brokers. Brokers play an important but often overlooked role in helping small businesses obtain health insurance coverage and resolve problems with health plans. 11 Brokers help small businesses identify what type of insurance is available at what price, fill out the paperwork and often resolve problems or grievances that arise. In the same way that benefit managers in large companies complain that the largest part of their day is spent resolving complaints, brokers often find themselves serving a similar function for their clients.

When Florida and California began statewide purchasing cooperatives for small businesses, the cooperatives were expected to save costs by bypassing brokers and their commissions. The purchasing cooperatives reversed strategies, however, when brokers steered clients elsewhere, and the cooperatives experienced lackluster membership growth. For example, CaliforniaChoice, a private purchasing cooperative organized by an insurance agency, has surpassed its competitor, PacAdvantage, in membership. Area health leaders attribute this, in part, to a better relationship with brokers. Even if tax credit recipients will be required to buy health insurance through purchasing pools, the pools still might want to use brokers rather than replicating their services.

Health Plan Participation

![]() ombining all tax credit recipients in a

limited number of purchasing pools

would greatly enhance the participation

of health plans because of the significant

market share these entities would represent.

Yet, health plans tend to be wary of

purchasing pools because of fears of

adverse selection and wanting to avoid

head-to-head competition. Health plans

would rather compete on variations in

benefit design, provider networks and

name-brand recognition than on price.

12

ombining all tax credit recipients in a

limited number of purchasing pools

would greatly enhance the participation

of health plans because of the significant

market share these entities would represent.

Yet, health plans tend to be wary of

purchasing pools because of fears of

adverse selection and wanting to avoid

head-to-head competition. Health plans

would rather compete on variations in

benefit design, provider networks and

name-brand recognition than on price.

12

Membership and Administration. Purchasing pools must seek a balance between their mission of extending coverage to the previously uninsured and avoiding adverse selection. Pools with lenient membership criteria tend to attract higher risks. For example, the typical employer obtaining coverage through the Miami CHPA had one or two employees, and CHPA’s permissive membership policies exacerbated risk selection. According to health leaders in that market, CHPA provided a gateway for high-risk individuals to establish phony businesses to obtain health insurance. In general, very small firms behave like people with individual coverage, obtaining insurance only when needed and then dropping coverage after the need passes. This churning results in higher claims experience and higher administrative costs. In contrast, Cleveland’s Council of Small Enterprises (COSE) has an average group size of six and charges a $450 membership fee that discourages single-person membership. In addition, COSE’s medical underwriting standards are the same as those of insurers in the market, so COSE’s risks are viewed as the same as or better than the rest of the market. 13

Expectations that purchasing pools would garner large savings in administration similar to large employers’ never materialized. The administrative costs of marketing, enrollment processing and premium collection for individuals and small businesses will always be higher than for large companies, regardless of whether this function is performed by health plans or purchasing pools. Yet, because purchasing pools have not gained sufficient market share, the health plans and pools have failed to achieve efficiencies by maintaining duplicate administrative functions. 14 However, the potential for administrative cost savings is much greater because overhead costs are substantially higher in the individual market than in the group market.

Expanding Choice. Purchasing pools have been successful in providing choice for workers in small firms. For example, in Seattle, the Employers’ Health Purchasing Cooperative structures offerings so the employer chooses one of two plans and one of three benefit designs. The employee then chooses a plan based on the extent of managed care and copayments. In one study of three statewide purchasing pools, about 80 percent of very small firms provided a choice of plans, compared with 15 percent of small firms that did not participate in any pool. 15 In addition, employees took advantage of their choice of plans by making different enrollment decisions. 16

Too many choice offerings, however, can exacerbate risk selection. The Miami CHPA offered health plans from 10 different carriers to employees in each small firm. As a result, two of the plans with richer benefits experienced adverse selection. And although one California purchasing cooperative uses risk adjustment based on age and sex, it lost its preferred provider organization (PPO) offering because of adverse selection. The cooperative recently reintroduced a PPO product, but it is unclear whether it can avoid an unmanageable degree of adverse selection.

Further Issues to Address

![]() hen reviewing various tax credit proposals,

policy makers will need to consider not

only the amount of the subsidy and who

qualifies, but also how individuals will

obtain their coverage and whether they

will get value for their tax credit dollar.

Using the private market approach of

linking tax credits to purchasing pools

raises several significant issues, including

how many purchasing pools should be

allowed to compete, and how the pools

will fit within existing markets for individuals

and small businesses.

hen reviewing various tax credit proposals,

policy makers will need to consider not

only the amount of the subsidy and who

qualifies, but also how individuals will

obtain their coverage and whether they

will get value for their tax credit dollar.

Using the private market approach of

linking tax credits to purchasing pools

raises several significant issues, including

how many purchasing pools should be

allowed to compete, and how the pools

will fit within existing markets for individuals

and small businesses.

A policy linking tax credits to purchasing pools should require all individuals with tax credits to buy health insurance through private purchasing pools. 17 Policy makers would need to limit the number of purchasing pools competing within each state but would want more than a single pool to provide the competitive pressure needed to hold down costs. Having too many purchasing pools compete, on the other hand, will increase administrative costs and the potential for risk selection across the pools.

Policy makers also need to consider how a tax credit policy linked to purchasing pools may affect states’ individual and small group markets. To address risk selection problems, states have struggled to improve these markets through regulation. Even with such regulation, individuals and small groups will attempt to get the best deal, moving back and forth between these markets. 18 This "border crossing" can undermine reforms by reintroducing risk selection.

Other considerations are whether individuals and small businesses-in addition to tax credit recipients-will be allowed to participate in the authorized purchasing pools, and whether the authorized purchasing pools must adhere to all current state regulations or may be exempt from some of them, such as state-mandated benefits. 19 Each of these choices will have implications for the purchasing pools and individuals and small employers not participating in the pools.

Regardless of whether a tax credit policy relies on the individual market, employer-sponsored insurance, public programs or purchasing pools, policy makers will face the difficult problem of insuring the highest risks. Tax credits linked to purchasing pools address this issue by combining risks similar to a large employer. Another way is to reform the individual market, such as by establishing a high-risk pool and standardizing benefits. 20 A high-risk pool that removes 1 percent of the highest-risk cases will reduce premium costs by 14 percent. 21 Whatever path is chosen, if a tax credit policy is going to ensure that people who have the greatest difficulty obtaining coverage, such as the chronically ill, can afford coverage, then policy makers must address the fundamental issue of risk selection.

Notes

1. The Relief, Equity, Access and Coverage for Health Act (REACH) was introduced by Sens. James Jeffords (R-Vt.), Bill Frist (R-Tenn.), Olympia Snowe (R-Maine), Lincoln Chafee (R-R.I.), John Breaux (D-La.), Blanche Lincoln (D-Ark.) and Thomas Carper (D-Del.).

2. Swartz, Katherine, “Markets for Individual Health Insurance: Can We Make Them Work with Incentives to Purchase Insurance?” The Commonwealth Fund, Publication No. 421 (December 2000).

3. Pauly, Mark, and Bradley Herring, “Expanding Coverage Via Tax Credits: Trade-Offs and Outcomes,” Health Affairs, Vol. 20, No. 1 (January/February 2001).

4. Pauly, Mark, Allison Percy, and Bradley Herring, “Individual versus Job-Based Health Insurance: Weighing the Pros and Cons,” Health Affairs, Vol. 18, No. 6 (November/December 1999).

5. Cunningham, Peter J., Elizabeth Schaefer and Christopher Hogan, “Who Declines Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance and Is Uninsured?” Issue Brief No. 22 (October 1999).

6. Glied, Sherry A., “Challenges and Options for Increasing the Number of Americans with Health Insurance,” The Commonwealth Fund, Publication No. 415 (December 2000).

7. Duchon, Lisa, et al., “Listening to Workers: Challenges for Employer-Sponsored Coverage in the 21st Century,” The Commonwealth Fund, Publication No. 361 (January 2000).

8. Curtis, Richard E., Edward Neuschler and Rafe Forland, “Private Purchasing Pools to Harness Individual Tax Credits for Consumers,” The Commonwealth Fund, Publication No. 413 (December 2000).

9. Wicks, Elliot K., and Mark A. Hall, “Purchasing Cooperatives for Small Employers: Performance and Prospects,” The Milbank Quarterly, Vol. 78, No. 4 (2000).

10. Long, Stephen H., and M. Susan Marquis, “Have Small-Group Health Insurance Purchasing Alliances Increased Coverage?” Health Affairs, Vol. 20, No. 1 (January/February 2001).

11. Hall, Mark A., “The Role of Independent Agents in the Success of Health Insurance Market Reforms,” The Milbank Quarterly, Vol. 78, No. 1 (2000).

12. Hall, Mark A., Elliot K. Wicks and Janice S. Lawlor, “HealthMarts, HIPCs, MEWAs, and AHPs: A Guide for the Perplexed,” Health Affairs, Vol. 20, No. 1 (January/February 2001).

13. Wicks, Elliot K., Mark A. Hall, and Jack A. Meyer, “Barriers to Small-Group Purchasing Cooperatives: Purchasing Health Coverage for Small Employers,” Economic and Social Research Institute, March 2000.

15. Long, Stephen H., and M. Susan Marquis, “Pooled Purchasing: Who Are the Players?” Health Affairs, Vol. 18, No. 4 (July/August 1999).

16. Long et al., January/February 2001.

17. Curtis et al., December 2000.18. Hall, Mark A., “The Geography of Health Insurance Regulation,” Health Affairs, Vol. 19, No. 2 (March/April 2000).

19. Curtis et al., December 2000.

ISSUE BRIEFS are published by Health System Change.

President: Paul B. GinsburgDirector of Public Affairs: Ann C. Greiner

Editor: The Stein Group