Insurance Coverage & Costs

Access to Care

Quality & Care Delivery

Health Care Markets

Employers/Consumers

Health Plans

Hospitals

Physicians

Insurance Coverage & Costs

Access to Care

Quality & Care Delivery

Health Care Markets

Employers/Consumers

Health Plans

Hospitals

Physicians

Issue Briefs

Data Bulletins

Research Briefs

Policy Analyses

Community Reports

Journal Articles

Other Publications

Surveys

Site Visits

Design and Methods

Data Files

|

Hospitals Compete for Specialty Care

Greenville, S.C.

Community Report No. 07

Spring 2001

Glen P. Mays, Sally Trude, Lawrence P. Casalino, Patricia Lichiello, Bradley C. Strunk, Jeffrey Stoddard

n November 2000, a team of

researchers visited Greenville, S.C., to

study that community’s health system,

how it is changing and the effects of

those changes on consumers. The

Center for Studying Health System

Change (HSC), as part of the

Community Tracking Study, interviewed

more than 50 leaders in the

health care market. Greenville is one of

12 communities tracked by HSC every

two years through site visits and surveys.

Individual community reports

are published for each round of site

visits. The first two site visits to

Greenville, in 1996 and 1998, provided

baseline and initial trend information

against which changes are tracked.

The Greenville market includes

Greenville, Spartanburg, Anderson,

Cherokee and Pickens counties. n November 2000, a team of

researchers visited Greenville, S.C., to

study that community’s health system,

how it is changing and the effects of

those changes on consumers. The

Center for Studying Health System

Change (HSC), as part of the

Community Tracking Study, interviewed

more than 50 leaders in the

health care market. Greenville is one of

12 communities tracked by HSC every

two years through site visits and surveys.

Individual community reports

are published for each round of site

visits. The first two site visits to

Greenville, in 1996 and 1998, provided

baseline and initial trend information

against which changes are tracked.

The Greenville market includes

Greenville, Spartanburg, Anderson,

Cherokee and Pickens counties.

Greenville’s continued population growth and economic

development have kept the area’s health care providers

busy and profitable. Hospitals have expanded specialty

services while abandoning efforts to build primary care

capacity. Health maintenance organization (HMO) enrollment

has remained low over the past two years, and distinctions

between HMOs and preferred provider organizations

(PPOs) have diminished. Rising insurance premiums

have prompted some small employers to drop coverage

for dependents, raising concerns about growth of the uninsured

population. Fortunately, access to care for under-served

populations has continued to improve through

cooperative efforts among safety net providers and other

community organizations.

Other significant developments over the past two years

include:

- Several area hospitals have received state approval to

offer tertiary care services, leading to more intense

competition for patients.

- Providers have discontinued efforts to build infrastructure

for managed care risk contracting.

- Projected state budget shortfalls have begun to threaten

the long-term stability of government health insurance

programs, including Medicaid and the State Children’s

Health Insurance Program (SCHIP).

Competition Intensifies as Hospitals Strengthen Specialty Care

reenville’s hospital systems have remained financially sound

and powerful in the local market over the past two years. Steady population growth

has kept most hospitals operating at full capacity, strengthening their negotiating

leverage with health plans and physicians. After a failed merger attempt among

three of the region’s largest hospital systems in 1996, hospitals have concentrated

on relatively distinct submarkets generally defined by the municipal boundaries

of Greenville, Spartanburg and Anderson. Historically, the competition for patients

across these submarkets has been fairly limited, and Greenville Hospital System

(GHS) has been the dominant local provider of tertiary care and other specialty

services.

Since 1998, however, most area

hospitals have strengthened their ability

to deliver profitable specialty services such

as cardiology, oncology and orthopedics.

Consequently, hospitals have begun to

compete more aggressively for patients

and revenue in these services. Spartanburg

Regional Healthcare System, for example,

built a new cancer center and increased

its capacity to perform cardiac surgery.

Spartanburg’s other major hospital, Mary

Black Memorial Hospital, recently formed

an alliance with a national oncology service

provider to expand the hospital’s cancer

services. Similarly, Anderson Area Medical

Center received state approval to open a

cardiac surgery center.

During this same period, Greenville’s

Bon Secours St. Francis Hospital opened

new cardiac surgery and bone marrow

transplantation centers and received state

approval to provide an expanded array of

neonatal intensive care services. These new

services were expected to improve the hospital’s

competitive position relative to the

nearby GHS, which has continued to offer

deep discounts to health insurers that

exclude St. Francis from their networks.

These exclusive contracts have remained in

place despite the expanded array of services

available at St. Francis, helping GHS to

retain its dominant position in the market.

Historically, state certificate-of-need

(CON) regulations have restricted competition

in the provision of tertiary care

services such as cardiac surgery and oncology,

but the area’s steady population growth

has prompted the state to approve recent

hospital requests to expand service offerings.

There has been little evidence to suggest

that recent service expansions have resulted

in unnecessary duplication and excess

capacity, as some local employers and

health plans feared. To the contrary, many

observers expected the recent expansions to

help alleviate emerging capacity constraints

caused by the region’s population growth. reenville’s hospital systems have remained financially sound

and powerful in the local market over the past two years. Steady population growth

has kept most hospitals operating at full capacity, strengthening their negotiating

leverage with health plans and physicians. After a failed merger attempt among

three of the region’s largest hospital systems in 1996, hospitals have concentrated

on relatively distinct submarkets generally defined by the municipal boundaries

of Greenville, Spartanburg and Anderson. Historically, the competition for patients

across these submarkets has been fairly limited, and Greenville Hospital System

(GHS) has been the dominant local provider of tertiary care and other specialty

services.

Since 1998, however, most area

hospitals have strengthened their ability

to deliver profitable specialty services such

as cardiology, oncology and orthopedics.

Consequently, hospitals have begun to

compete more aggressively for patients

and revenue in these services. Spartanburg

Regional Healthcare System, for example,

built a new cancer center and increased

its capacity to perform cardiac surgery.

Spartanburg’s other major hospital, Mary

Black Memorial Hospital, recently formed

an alliance with a national oncology service

provider to expand the hospital’s cancer

services. Similarly, Anderson Area Medical

Center received state approval to open a

cardiac surgery center.

During this same period, Greenville’s

Bon Secours St. Francis Hospital opened

new cardiac surgery and bone marrow

transplantation centers and received state

approval to provide an expanded array of

neonatal intensive care services. These new

services were expected to improve the hospital’s

competitive position relative to the

nearby GHS, which has continued to offer

deep discounts to health insurers that

exclude St. Francis from their networks.

These exclusive contracts have remained in

place despite the expanded array of services

available at St. Francis, helping GHS to

retain its dominant position in the market.

Historically, state certificate-of-need

(CON) regulations have restricted competition

in the provision of tertiary care

services such as cardiac surgery and oncology,

but the area’s steady population growth

has prompted the state to approve recent

hospital requests to expand service offerings.

There has been little evidence to suggest

that recent service expansions have resulted

in unnecessary duplication and excess

capacity, as some local employers and

health plans feared. To the contrary, many

observers expected the recent expansions to

help alleviate emerging capacity constraints

caused by the region’s population growth.

Providers Discontinue Preparations for Managed Care

hile expanding specialty services, Greenville-area providers

have discontinued efforts to prepare for risk contracting with health plans. Before

1999, most hospitals in Greenville were actively purchasing primary care practices

across the region and investing in care management and quality-improvement initiatives-activities

that were designed to help hospitals attract and manage risk contracts with health

plans. Providers that experimented with risk contracting, however, found these

arrangements to be unprofitable given the area’s limited HMO enrollment, low capitation

payments and the high overhead costs associated with managing these contracts.

Consequently, most providers have lost all interest in risk contracting. For similar

reasons, Greenville’s only provider-sponsored health plan, HealthFirst, was dissolved

by its three hospital owners at the end of 1999 after only two years of operation.

Because risk contracting failed to

develop, hospitals have slowed their drive to

acquire primary care capacity over the past

two years. Moreover, some hospitals have

scaled back efforts to develop care management

initiatives designed to reduce utilization

and improve service delivery. In 1998,

several of Greenville’s leading hospital systems

had begun to develop and implement

such initiatives for complex and high-cost

medical conditions. According to hospital

administrators, some of these programs

could not be sustained financially because

health plan contracts did not reward hospital

efforts to prevent readmissions and

improve outpatient recovery. A few care

management initiatives have continued to

operate in hospitals-such as Spartanburg

Regional Healthcare System’s programs for

congestive heart failure and diabetes-but

efforts to expand these programs to new

disease areas have been suspended. Some

community leaders have become concerned

that local providers no longer face significant

external pressures to improve the

quality and efficiency of clinical practice. hile expanding specialty services, Greenville-area providers

have discontinued efforts to prepare for risk contracting with health plans. Before

1999, most hospitals in Greenville were actively purchasing primary care practices

across the region and investing in care management and quality-improvement initiatives-activities

that were designed to help hospitals attract and manage risk contracts with health

plans. Providers that experimented with risk contracting, however, found these

arrangements to be unprofitable given the area’s limited HMO enrollment, low capitation

payments and the high overhead costs associated with managing these contracts.

Consequently, most providers have lost all interest in risk contracting. For similar

reasons, Greenville’s only provider-sponsored health plan, HealthFirst, was dissolved

by its three hospital owners at the end of 1999 after only two years of operation.

Because risk contracting failed to

develop, hospitals have slowed their drive to

acquire primary care capacity over the past

two years. Moreover, some hospitals have

scaled back efforts to develop care management

initiatives designed to reduce utilization

and improve service delivery. In 1998,

several of Greenville’s leading hospital systems

had begun to develop and implement

such initiatives for complex and high-cost

medical conditions. According to hospital

administrators, some of these programs

could not be sustained financially because

health plan contracts did not reward hospital

efforts to prevent readmissions and

improve outpatient recovery. A few care

management initiatives have continued to

operate in hospitals-such as Spartanburg

Regional Healthcare System’s programs for

congestive heart failure and diabetes-but

efforts to expand these programs to new

disease areas have been suspended. Some

community leaders have become concerned

that local providers no longer face significant

external pressures to improve the

quality and efficiency of clinical practice.

Physician-Hospital Relationships Remain Strong

hysicians have remained tightly aligned

with Greenville-area hospitals, despite the

hospitals’ waning interest in building primary

care capacity. During the mid-1990s,

hospitals pursued close relationships with

physicians to prepare for risk contracting,

either through physician-hospital organizations

(PHOs) or by acquiring physician

practices. By 1997, nearly 75 percent of

Greenville’s primary care physicians were

employed by hospitals, and most hospitals

had developed active PHOs. Though no

longer focused on risk contracting, many

of these arrangements have remained intact

and have become important vehicles for exercising

negotiating leverage with health plans.

Indeed, most Greenville-area hospitals

have succeeded in negotiating substantial

payment increases from health plans over

the past two years, and plans have attributed

these successes in part to the tight alignment

between physicians and hospitals. For example,

GHS has continued to employ nearly

180 physicians in both primary care and

specialty disciplines, helping the system to

remain an indispensable provider in health

plan networks. Similarly, Spartanburg

Regional Healthcare System’s PHO, Regional

HealthPlus, has become an important vehicle

for both HMO and PPO contracting.

Because the hospital and its participating

physicians share financial risk through a

withhold arrangement, the PHO reportedly

is able to negotiate fee-for-service

payment rates collectively on behalf of

the participating providers without raising

antitrust concerns.

To date, the only Greenville-area hospital

that has decided to sell its physician

practices is St. Francis. This hospital has

not been successful in using its 20 primary

care practices and 75 employed physicians

to gain negotiating leverage with health

plans, largely because two of the state’s

largest plans exclude it from their networks

to obtain discounts from GHS.

Physicians have found few nonhospital-based

strategies for exerting their leverage

collectively in the Greenville market.

Large independent physician groups have

remained absent from the Greenville area

since the demise of Carolina Multispecialty

Associates (CMA) at the end of 1998. CMA

had been organized several years earlier to

participate in risk contracts with health

plans, but its administrative infrastructure

proved too costly to sustain once these contracts

failed to develop in the market. With

CMA’s demise, several small single-specialty

groups have gained negotiating leverage

with plans and hospitals because of their

local dominance in specific lines of service.

Some of these single-specialty groups

have developed independent outpatient

surgery and imaging facilities that potentially

could compete with hospital-based

services, but so far these ventures have

remained limited in scope and scale.

Greenville-area hospitals generally have

been successful in using the state’s CON

regulations to block competition from free-standing

facilities. However, hospital administrators

expressed concern that proposed

changes to the state’s CON regulations could

allow more of these facilities to develop,

ultimately compromising the financial

viability of hospitals by stripping away

profitable specialty service lines. hysicians have remained tightly aligned

with Greenville-area hospitals, despite the

hospitals’ waning interest in building primary

care capacity. During the mid-1990s,

hospitals pursued close relationships with

physicians to prepare for risk contracting,

either through physician-hospital organizations

(PHOs) or by acquiring physician

practices. By 1997, nearly 75 percent of

Greenville’s primary care physicians were

employed by hospitals, and most hospitals

had developed active PHOs. Though no

longer focused on risk contracting, many

of these arrangements have remained intact

and have become important vehicles for exercising

negotiating leverage with health plans.

Indeed, most Greenville-area hospitals

have succeeded in negotiating substantial

payment increases from health plans over

the past two years, and plans have attributed

these successes in part to the tight alignment

between physicians and hospitals. For example,

GHS has continued to employ nearly

180 physicians in both primary care and

specialty disciplines, helping the system to

remain an indispensable provider in health

plan networks. Similarly, Spartanburg

Regional Healthcare System’s PHO, Regional

HealthPlus, has become an important vehicle

for both HMO and PPO contracting.

Because the hospital and its participating

physicians share financial risk through a

withhold arrangement, the PHO reportedly

is able to negotiate fee-for-service

payment rates collectively on behalf of

the participating providers without raising

antitrust concerns.

To date, the only Greenville-area hospital

that has decided to sell its physician

practices is St. Francis. This hospital has

not been successful in using its 20 primary

care practices and 75 employed physicians

to gain negotiating leverage with health

plans, largely because two of the state’s

largest plans exclude it from their networks

to obtain discounts from GHS.

Physicians have found few nonhospital-based

strategies for exerting their leverage

collectively in the Greenville market.

Large independent physician groups have

remained absent from the Greenville area

since the demise of Carolina Multispecialty

Associates (CMA) at the end of 1998. CMA

had been organized several years earlier to

participate in risk contracts with health

plans, but its administrative infrastructure

proved too costly to sustain once these contracts

failed to develop in the market. With

CMA’s demise, several small single-specialty

groups have gained negotiating leverage

with plans and hospitals because of their

local dominance in specific lines of service.

Some of these single-specialty groups

have developed independent outpatient

surgery and imaging facilities that potentially

could compete with hospital-based

services, but so far these ventures have

remained limited in scope and scale.

Greenville-area hospitals generally have

been successful in using the state’s CON

regulations to block competition from free-standing

facilities. However, hospital administrators

expressed concern that proposed

changes to the state’s CON regulations could

allow more of these facilities to develop,

ultimately compromising the financial

viability of hospitals by stripping away

profitable specialty service lines.

HMOs Fail to Gain Ground

MOs have not gained substantial market share in Greenville’s

PPO-dominated health insurance market over the past two years. Blue Cross Blue

Shield of South Carolina has remained the dominant insurer, with approximately

40 percent of the commercial market, largely because of the popularity of its

PPO. One reason that HMOs have not grown as expected is that they have been unable

to offer purchasers and consumers substantial cost savings over PPOs. Health plan

administrators indicated that their short-lived experiments with risk contracting

were not effective in containing HMO costs because many of the area’s high-cost

providers declined to participate in such contracts. Moreover, because HMO enrollment

and physician supply have remained low in this market, many providers have become

unwilling to offer larger discounts to HMO products than to PPO products. As a

result, premiums for HMOs have risen sharply over the past two years and have

become comparable to PPO premiums.

In an effort to attract additional HMO

membership, several health plans have introduced

new direct-access HMO products

that do not require referrals for specialty

care. Three of Greenville’s largest insurance

carriers have launched some variant of

this product over the past year, largely in

response to the success that one plan experienced

with its direct-access HMO during

1998 and 1999. That success has contributed

to a modest growth in HMO enrollment

over the past two years-from 11 percent

of individuals with private insurance in 1998

to 14 percent in 2000. The emergence of

direct-access products, however, has blurred

the distinction between HMO and PPO

products. Benefits, product features and

premiums have become remarkably similar

across these once-distinct product lines.

As HMOs and PPOs have converged

in product design, HMOs have ceased to

function as low-cost health insurance

options for small businesses and other

purchasers challenged by rising premiums.

In response, several plans have stepped up

marketing of lower-priced HMO and PPO

products that have higher deductibles and

coinsurance levels for enrollees or that use

partial self-insurance arrangements that

require employers to cover a greater share

of health care costs. Examples include

products that require enrollees to pay 30

percent or more of each claim, and minimum

premium products that require

purchasers to pay all claims below an established

amount. Some observers expressed

concern that these types of products could

leave consumers and small businesses with

inadequate insurance benefits, while others

believed that few employers would purchase

such products. MOs have not gained substantial market share in Greenville’s

PPO-dominated health insurance market over the past two years. Blue Cross Blue

Shield of South Carolina has remained the dominant insurer, with approximately

40 percent of the commercial market, largely because of the popularity of its

PPO. One reason that HMOs have not grown as expected is that they have been unable

to offer purchasers and consumers substantial cost savings over PPOs. Health plan

administrators indicated that their short-lived experiments with risk contracting

were not effective in containing HMO costs because many of the area’s high-cost

providers declined to participate in such contracts. Moreover, because HMO enrollment

and physician supply have remained low in this market, many providers have become

unwilling to offer larger discounts to HMO products than to PPO products. As a

result, premiums for HMOs have risen sharply over the past two years and have

become comparable to PPO premiums.

In an effort to attract additional HMO

membership, several health plans have introduced

new direct-access HMO products

that do not require referrals for specialty

care. Three of Greenville’s largest insurance

carriers have launched some variant of

this product over the past year, largely in

response to the success that one plan experienced

with its direct-access HMO during

1998 and 1999. That success has contributed

to a modest growth in HMO enrollment

over the past two years-from 11 percent

of individuals with private insurance in 1998

to 14 percent in 2000. The emergence of

direct-access products, however, has blurred

the distinction between HMO and PPO

products. Benefits, product features and

premiums have become remarkably similar

across these once-distinct product lines.

As HMOs and PPOs have converged

in product design, HMOs have ceased to

function as low-cost health insurance

options for small businesses and other

purchasers challenged by rising premiums.

In response, several plans have stepped up

marketing of lower-priced HMO and PPO

products that have higher deductibles and

coinsurance levels for enrollees or that use

partial self-insurance arrangements that

require employers to cover a greater share

of health care costs. Examples include

products that require enrollees to pay 30

percent or more of each claim, and minimum

premium products that require

purchasers to pay all claims below an established

amount. Some observers expressed

concern that these types of products could

leave consumers and small businesses with

inadequate insurance benefits, while others

believed that few employers would purchase

such products.

Small Businesses Struggle with Escalating Premiums

irroring national trends, employers in the Greenville market

have experienced significant premium increases over the past two years. Large

employers have not responded to the premium increases with major changes in their

health benefits programs as yet. Small employers, however, have faced more extreme

premium increases than their larger counterparts, and some have begun to drop

coverage for their employees’ dependents.

Many community leaders expressed

concern about the rapid decline in the

number of insurance carriers offering

affordable products to small businesses.

Although six carriers offer health insurance

products to businesses with fewer than 50

employees, employers considered only

three of these products to be affordable.

Insurance carriers have incurred large

financial losses in the small group business

line in the past two years, and 17 plans have

withdrawn from the state’s small group

market since mid-1997. Many respondents

blamed the 1996 federal Health

Insurance Portability and Accountability

Act (HIPAA) for considerable turmoil in

the small group market. However, the fact

that 46 insurers remain in this market

statewide suggests that exits were precipitated

in part by an overcrowded market.

The Greater Greenville Chamber of

Commerce and the newly formed Business

Council of South Carolina are each taking

steps to gain relief for small businesses in

purchasing health insurance. The Chamber

of Commerce is working to amend state

laws that limit businesses’ ability to develop

associations that enhance purchasing

power in the insurance market. In particular,

it seeks legislation to allow small

business associations to pool risk under a

single contract with insurance carriers, create

risk tiers for different types of association

members and design and purchase customized

health insurance products.

In a separate effort, the Business

Council of South Carolina is attempting

to increase membership in its newly

formed purchasing association. Additionally,

the organization is encouraging state officials

to develop a high-risk insurance pool

demonstration program that would provide

state-subsidized coverage for small

businesses unable to obtain coverage in

the private market because of their high

claims experience. It is unclear whether

this program will go beyond the proposal

stage, however, because of growing state

budget pressures. irroring national trends, employers in the Greenville market

have experienced significant premium increases over the past two years. Large

employers have not responded to the premium increases with major changes in their

health benefits programs as yet. Small employers, however, have faced more extreme

premium increases than their larger counterparts, and some have begun to drop

coverage for their employees’ dependents.

Many community leaders expressed

concern about the rapid decline in the

number of insurance carriers offering

affordable products to small businesses.

Although six carriers offer health insurance

products to businesses with fewer than 50

employees, employers considered only

three of these products to be affordable.

Insurance carriers have incurred large

financial losses in the small group business

line in the past two years, and 17 plans have

withdrawn from the state’s small group

market since mid-1997. Many respondents

blamed the 1996 federal Health

Insurance Portability and Accountability

Act (HIPAA) for considerable turmoil in

the small group market. However, the fact

that 46 insurers remain in this market

statewide suggests that exits were precipitated

in part by an overcrowded market.

The Greater Greenville Chamber of

Commerce and the newly formed Business

Council of South Carolina are each taking

steps to gain relief for small businesses in

purchasing health insurance. The Chamber

of Commerce is working to amend state

laws that limit businesses’ ability to develop

associations that enhance purchasing

power in the insurance market. In particular,

it seeks legislation to allow small

business associations to pool risk under a

single contract with insurance carriers, create

risk tiers for different types of association

members and design and purchase customized

health insurance products.

In a separate effort, the Business

Council of South Carolina is attempting

to increase membership in its newly

formed purchasing association. Additionally,

the organization is encouraging state officials

to develop a high-risk insurance pool

demonstration program that would provide

state-subsidized coverage for small

businesses unable to obtain coverage in

the private market because of their high

claims experience. It is unclear whether

this program will go beyond the proposal

stage, however, because of growing state

budget pressures.

Community Mobilizes Support for Expanding Safety Net

he Greenville community has continued to expand access to

care for underserved populations through partnerships among safety net providers

and other community organizations. After significant gaps were identified four

years ago, the United Way organized a community-wide needs assessment that found

that more than 10 percent of residents were uninsured, and another 20 percent

were underinsured or otherwise medically underserved. The assessment triggered

several capital improvement efforts to expand local capacity to care for individuals

who lack access to medical care providers. Greenville’s two community health clinics

renovated their facilities and expanded clinical services, and several Greenville-area

hospitals committed funds to provide ongoing support for these improvements.

Efforts to expand the capacity of

Greenville’s safety net have continued

over the past two years, with a special

focus on coordinated, community-wide

efforts to improve access to care. As an

outgrowth of the 1997 assessment process,

local organizations formed the Community

Health Alliance (CHA) in 1999 to bring

together a broad range of organizations

interested in improving access to health

care, including health, civic, business and

faith-based organizations. The CHA has

coordinated efforts to develop satellite

community clinics in areas underserved

by medical care providers. It is also working

to increase the amount of charity care

delivered by local physicians, in part by

establishing a community-wide database

to recognize and monitor physician charity

care. Most recently, the CHA has undertaken

a study of the health insurance

benefits offered by small businesses in

hopes of designing a local program to

provide coverage to the uninsured

employees of these businesses.

Despite recent successes, safety net

providers remain concerned about access

to care for the uninsured and underserved.

Inadequate public transportation has

continued to pose barriers to health care

for many low-income Greenville County

residents. In 1996, the Greenville Transit

Authority was forced to reduce hours

and service areas because of funding

shortfalls. Community organizations

subsequently pieced together a medical

transportation network using public and

private funding, but local policy makers

have failed to adopt a permanent solution

to Greenville’s transportation problems.

At the same time, rising health insurance

premiums have raised fears among safety

net providers that private insurance coverage

has begun to erode and threatens to

overwhelm the community’s recent successes

in expanding care for the underserved. he Greenville community has continued to expand access to

care for underserved populations through partnerships among safety net providers

and other community organizations. After significant gaps were identified four

years ago, the United Way organized a community-wide needs assessment that found

that more than 10 percent of residents were uninsured, and another 20 percent

were underinsured or otherwise medically underserved. The assessment triggered

several capital improvement efforts to expand local capacity to care for individuals

who lack access to medical care providers. Greenville’s two community health clinics

renovated their facilities and expanded clinical services, and several Greenville-area

hospitals committed funds to provide ongoing support for these improvements.

Efforts to expand the capacity of

Greenville’s safety net have continued

over the past two years, with a special

focus on coordinated, community-wide

efforts to improve access to care. As an

outgrowth of the 1997 assessment process,

local organizations formed the Community

Health Alliance (CHA) in 1999 to bring

together a broad range of organizations

interested in improving access to health

care, including health, civic, business and

faith-based organizations. The CHA has

coordinated efforts to develop satellite

community clinics in areas underserved

by medical care providers. It is also working

to increase the amount of charity care

delivered by local physicians, in part by

establishing a community-wide database

to recognize and monitor physician charity

care. Most recently, the CHA has undertaken

a study of the health insurance

benefits offered by small businesses in

hopes of designing a local program to

provide coverage to the uninsured

employees of these businesses.

Despite recent successes, safety net

providers remain concerned about access

to care for the uninsured and underserved.

Inadequate public transportation has

continued to pose barriers to health care

for many low-income Greenville County

residents. In 1996, the Greenville Transit

Authority was forced to reduce hours

and service areas because of funding

shortfalls. Community organizations

subsequently pieced together a medical

transportation network using public and

private funding, but local policy makers

have failed to adopt a permanent solution

to Greenville’s transportation problems.

At the same time, rising health insurance

premiums have raised fears among safety

net providers that private insurance coverage

has begun to erode and threatens to

overwhelm the community’s recent successes

in expanding care for the underserved.

Medicaid Program Faces State Budget Pressures

ecent expansions in state health care programs have bolstered

insurance coverage in Greenville and statewide, but a looming state budget crisis

in South Carolina has created uncertainty about the sustainability of these expansions.

In 1997, South Carolina’s Medicaid/SCHIP expansion for children, Partners for

Healthy Children, which covers children in households with incomes up to 150 percent

of the federal poverty level, brought in nearly 150,000 new Medicaid/SCHIP enrollees

statewide- almost twice the number that had been expected. As a result of this

new enrollment and other recent expansions in Medicaid benefits and coverage,

the state’s Medicaid expenses exceeded its year 2000 budget.

As a stopgap measure, South Carolina

used funds from its settlement with the

tobacco industry and other nonrecurring

state funds to address the budget shortfall.

However, this funding will not be available

to meet the state’s financial obligations in

subsequent years. As a result, the state faces

a Medicaid funding deficit that could reach

$300 million in 2001.

Despite the threat of a state health

care financing crisis, South Carolina’s

policy makers have remained cool toward

health care cost-containment strategies that

rely on managed care. The state has chosen

not to implement a program of mandatory

HMO enrollment for Medicaid recipients,

and it has allowed enrollment in its voluntary

Medicaid managed care program to

remain low over the past four years.

Statewide, only one plan currently participates

in the voluntary program, and most

Medicaid recipients have chosen to remain

in one of the program’s enhanced fee-for-service

options. The Greenville area has

been without a Medicaid HMO since the

now-defunct HealthFirst plan discontinued

Medicaid participation in 1998.

South Carolina’s Medicaid program

has continued to struggle with low levels of

private physician participation-a problem

that could be exacerbated if the state’s budget shortfall leads to Medicaid payment

cuts. Fee-for-service physician payments

under Medicaid have remained low, discouraging

physician participation in a

community already underserved by private

physicians. Greenville’s safety net providers,

therefore, have remained primary sources

of care, not only for uninsured populations,

but also for those covered by

Medicaid. Consequently, the state’s looming

budget crisis has generated concerns

about the financial stability of Greenville’s

safety net providers. ecent expansions in state health care programs have bolstered

insurance coverage in Greenville and statewide, but a looming state budget crisis

in South Carolina has created uncertainty about the sustainability of these expansions.

In 1997, South Carolina’s Medicaid/SCHIP expansion for children, Partners for

Healthy Children, which covers children in households with incomes up to 150 percent

of the federal poverty level, brought in nearly 150,000 new Medicaid/SCHIP enrollees

statewide- almost twice the number that had been expected. As a result of this

new enrollment and other recent expansions in Medicaid benefits and coverage,

the state’s Medicaid expenses exceeded its year 2000 budget.

As a stopgap measure, South Carolina

used funds from its settlement with the

tobacco industry and other nonrecurring

state funds to address the budget shortfall.

However, this funding will not be available

to meet the state’s financial obligations in

subsequent years. As a result, the state faces

a Medicaid funding deficit that could reach

$300 million in 2001.

Despite the threat of a state health

care financing crisis, South Carolina’s

policy makers have remained cool toward

health care cost-containment strategies that

rely on managed care. The state has chosen

not to implement a program of mandatory

HMO enrollment for Medicaid recipients,

and it has allowed enrollment in its voluntary

Medicaid managed care program to

remain low over the past four years.

Statewide, only one plan currently participates

in the voluntary program, and most

Medicaid recipients have chosen to remain

in one of the program’s enhanced fee-for-service

options. The Greenville area has

been without a Medicaid HMO since the

now-defunct HealthFirst plan discontinued

Medicaid participation in 1998.

South Carolina’s Medicaid program

has continued to struggle with low levels of

private physician participation-a problem

that could be exacerbated if the state’s budget shortfall leads to Medicaid payment

cuts. Fee-for-service physician payments

under Medicaid have remained low, discouraging

physician participation in a

community already underserved by private

physicians. Greenville’s safety net providers,

therefore, have remained primary sources

of care, not only for uninsured populations,

but also for those covered by

Medicaid. Consequently, the state’s looming

budget crisis has generated concerns

about the financial stability of Greenville’s

safety net providers.

Issues to Track

reenville’s hospitals have strengthened specialty services

over the past two years, while safety net providers have expanded capacity to

provide care for the uninsured and other underserved populations. Rising health

care costs, however, have threatened to erode private health insurance coverage

at a time when South Carolina’s publicly funded insurance programs face substantial

budget shortfalls. These developments raise new questions about how health care

delivery and access to care in Greenville may change in the future: reenville’s hospitals have strengthened specialty services

over the past two years, while safety net providers have expanded capacity to

provide care for the uninsured and other underserved populations. Rising health

care costs, however, have threatened to erode private health insurance coverage

at a time when South Carolina’s publicly funded insurance programs face substantial

budget shortfalls. These developments raise new questions about how health care

delivery and access to care in Greenville may change in the future:

- Will safety net providers be able to meet the needs of the area’s uninsured

and publicly insured-given booming population growth and the expected erosion

of small businesses’ provision of health insurance?

- How will growing hospital competition

for specialty services affect health care

costs, quality and access?

- Will efforts to develop health insurance purchasing associations be successful

in containing premiums and improving insurance coverage among small businesses?

- How will state budget pressures affect eligibility, benefits and provider

payments under the state’s Medicaid and SCHIP expansion programs?

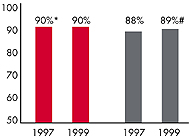

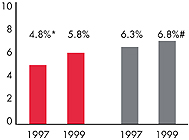

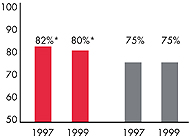

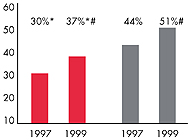

Greenville’s Experience with the Local Health System, 1997

and 1999

Background and Observations

| Greenville Demographics |

| Greenville |

Metropolitan areas above 200,000 population |

Population, July 1, 19991

929,565 |

| Population Change, 1990-19992

|

| 12% |

8.6% |

| Median Income3 |

| $24,967 |

$27,843 |

| Persons Living in Poverty3 |

| 14% |

14% |

| Persons Age 65 or Older3 |

| 13% |

11% |

Sources:

1. US Bureau of Census, 1999 Community Population Estimates

2. US Bureau of Census, 1990 & 1999 Community Population Estimates

3. Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1998-1999 |

| Health Insurance Status |

| Greenville |

Metropolitan areas above 200,000 population |

| Persons under Age 65 with No Health Insurance1 |

| 13% |

15% |

| Children under Age 18 with No Health Insurance1

|

| 9% |

11% |

| Employees Working for Private Firms that

Offer Coverage2 |

| 88% |

84% |

| Average Monthly Premium for Self-Only Coverage

under Employer-Sponsored Insurance2 |

| $158 |

$181 |

Sources:

1. Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1998-1999

2. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Employer Health Insurance Survey, 1997 |

| Health System Characteristics |

| Greenville |

Metropolitan areas above 200,000 population |

| Staffed Hospital Beds per 1,000 Population1

|

| 2.8 |

2.8 |

| Physicians per 1,000 Population2

|

| 1.7 |

2.3 |

| HMO Penetration, 19973 |

| 8.4% |

32% |

| HMO Penetration, 19994 |

| 13% |

36% |

Sources:

1. American Hospital Association, 1998

2. Area Resource File, 1998 (includes nonfederal, patient care physicians,

except radiologists, pathologists and anesthesiologists)

3. InterStudy Competitive Edge 8.1

4. InterStudy Competitive Edge 10.1 |

The Community Tracking Study, the major effort of the Center for Studying Health

System Change (HSC), tracks changes in the health system in 60 sites that are

representative of the nation. Every two years, HSC conducts surveys in all 60

communities and site visits in 12 communities. The Community Report series documents

the findings from the third round of site visits. Analyses based on site visit

and survey data from the Community Tracking Study are published by HSC in Issue

Briefs, Data Bulletins and peer-reviewed journals. These publications are

available at www.hschange.org.

Authors of the Greenville Community Report:

Glen P. Mays, Mathematica Policy Research, Inc.

Sally Trude, HSC

Lawrence P. Casalino, University of Chicago

Patricia Lichiello, University of Washington

Bradley C. Strunk, HSC

Jeffrey J. Stoddard, HSC

Community Reports are published by HSC:

President: Paul B. Ginsburg

Director of Site Visits: Cara S. Lesser

Director of Public Affairs: Ann C. Greiner

Editor: The Stein Group

|