Insurance Coverage & Costs

Access to Care

Quality & Care Delivery

Health Care Markets

Employers/Consumers

Health Plans

Hospitals

Physicians

Insurance Coverage & Costs

Access to Care

Quality & Care Delivery

Health Care Markets

Employers/Consumers

Health Plans

Hospitals

Physicians

Issue Briefs

Data Bulletins

Research Briefs

Policy Analyses

Community Reports

Journal Articles

Other Publications

Surveys

Site Visits

Design and Methods

Data Files

|

Hopes Dim for More Competition

Little Rock, Ark.

Community Report No. 08

Spring 2001

Debra A. Draper, Linda R. Brewster, Lawrence D. Brown, Lance Heineccius, Carolyn A. Watts, Laurie E. Felland, Elizabeth Eagan

n December 2000, a team of researchers visited Little Rock,

Ark., to study that community’s health system, how it is changing and the effects

of those changes on consumers. The Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC),

as part of the Community Tracking Study, interviewed more than 50 leaders in the

health care market. Little Rock is one of 12 communities tracked by HSC every

two years through site visits and surveys. Individual community reports are published

for each round of site visits. The first two site visits to Little Rock, in 1996

and 1998, provided baseline and initial trend information against which changes

are tracked. The Little Rock market includes Faulkner, Lonoke, Pulaski and Saline

counties. n December 2000, a team of researchers visited Little Rock,

Ark., to study that community’s health system, how it is changing and the effects

of those changes on consumers. The Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC),

as part of the Community Tracking Study, interviewed more than 50 leaders in the

health care market. Little Rock is one of 12 communities tracked by HSC every

two years through site visits and surveys. Individual community reports are published

for each round of site visits. The first two site visits to Little Rock, in 1996

and 1998, provided baseline and initial trend information against which changes

are tracked. The Little Rock market includes Faulkner, Lonoke, Pulaski and Saline

counties.

In 1998, Little Rock health plans and providers were optimistic that partnerships

with national firms would bolster their ability to challenge the powerful positions

of the market’s dominant health plan and provider system, Arkansas Blue Cross

Blue Shield (ABCBS) and Baptist Health System. Two years later, optimism has

faded as many of these would-be competitors face mounting financial and operational

problems, eroding their competitive potential. The departure of various health

insurers since 1998 has further constrained competition. As health care costs

increase and premiums rise, many observers fear that health insurance coverage

will become increasingly prohibitive for some consumers, leading to more uninsurance

in the state, where nearly one in seven persons currently goes without coverage.

Other important developments in Little Rock since 1998 include:

- Expansion of specialty services and capacity threatens to erode local hospitals’

revenue base.

- Premiums have escalated, as cost controls remain elusive.

- Financial problems have plagued the area’s predominant safety net provider.

ABCBS and Baptist Remain Powerful as Competitors Flail

ittle Rock’s health care market continues

to be dominated by ABCBS and Baptist

Health System, and their market positions

are bolstered by a close alliance. Since 1994,

ABCBS and Baptist have had a 50/50 joint

venture in the area’s largest health maintenance

organization (HMO), Health

Advantage HMO, and Baptist provides the

majority of services to members enrolled

in ABCBS’s HMO and PPO products.

The alliance reflects a statewide strategy

on the part of ABCBS to contract exclusively

with regionally dominant hospitals.

Some observers believe that these alliances

offer consumers a high-quality network at

a competitive price. Others say the alliances

inhibit competition and may eventually

lead to higher costs for consumers.

In Little Rock, the ABCBS-Baptist

affiliation has remained a powerful force

in the market, while financial and operational

problems have plagued other plans

and hospitals.

Plan Competition. ABCBS has more than 40 percent of the HMO market share

in Little Rock and close to 60 percent statewide. Much of the plan’s strength,

however, derives from its preferred provider organization (PPO), which has more

than 2.5 times the enrollment of its HMO, or approximately 440,000 enrollees statewide.

ABCBS’s closest HMO competitor

in Little Rock is United Healthcare,

which has a 25 percent share of local

HMO enrollees, but its visibility in the

market appears to be diminishing. Last

year, United combined its Arkansas and

Tennessee plans and moved many operations

to Tennessee, leading some observers

to question whether the plan intends to

remain in the Little Rock market.

Also on questionable footing is Little

Rock’s third-largest HMO, QCA QualChoice

Health Plan, with 19 percent local HMO

market share. Two years ago, this plan,

which is owned by the University of

Arkansas Medical Sciences (UAMS),

Tenet Healthcare Corp., and other equity

partners, was positioning itself to compete

more aggressively with the ABCBS-Baptist

alliance. Now, however, the plan

appears to be financially unstable, and

observers say that it may have been insolvent

at times because of difficulties in meeting

state risk reserve requirements. Whether

QualChoice’s equity partners will provide

additional funding is not known, and

observers suggest that a change for the

plan-perhaps new ownership or, in a

worst-case scenario, dissolution-may be

forthcoming.

Meanwhile, in December 2000,

CIGNA pulled out of the Arkansas HMO

market, affecting approximately 11,000

enrollees (some of whom switched to

CIGNA’s PPO or indemnity products the

plan continues to offer). Although CIGNA

was not a major player in Little Rock when

it exited the market, its departure was significant

in that it decreased the number of

health insurance options available to consumers

and reduced competition.

In all, approximately 40 insurers have

reportedly left the Arkansas market since

1998. Although it is unclear whether all of

these insurers offered health insurance

coverage, most observers agree that health

plan competition has decreased. Besides

CIGNA, other notable health plan exits

during the past two years include American

Investors Life and American Healthcare

Providers, Inc., each of which had close

to 20,000 PPO or HMO enrollees at peak

enrollment. Apart from Blue Cross Blue

Shield of Missouri, which entered the

market with HMO and PPO products,

no new plans have entered the Little Rock

market since 1998. Arkansas’ small size

and relatively rural demographics, along

with the poor health and lower socioeconomic

status of its population, have made

the state a less attractive place for health

plans to enter and operate.

Hospital Competition. Competition also has faltered in Little Rock’s hospital

market, and Baptist has maintained a significant competitive advantage. Although

Baptist’s market share in Little Rock proper is similar to that of its nearest

competitor, St. Vincent’s Health System, Baptist attracts significant additional

volume from referrals from 80 affiliated facilities located throughout the state.

To counter this competitive advantage, St. Vincent’s has invested in NovaSys Health

Network, a statewide provider network created in 1996 that includes 6,000 physicians

and 90 acute care hospitals. Despite its arrangement with NovaSys, St. Vincent’s

has not been as successful as Baptist in attracting referrals from outside the

market.

Moreover, recent financial and

operational problems have eroded the

competitive position of St. Vincent’s.

After providing an infusion of capital,

the Denver-based Catholic Health

Initiatives, which has owned St. Vincent’s

since 1997, curtailed additional support

because of its own financial losses.

Meanwhile, St. Vincent’s has experienced

declining volume in cardiac surgery following

the pullout of a major cardiology group

in 1997 that left to form the Arkansas

Heart Hospital. Additionally, St. Vincent’s

1998 acquisition of another local hospital

has reportedly further strained its

finances. At the same time, St. Vincent’s

has experienced staff reductions and

multiple changes in executive management

over the past two years, and, in

June 2000, it became the first private

Arkansas hospital with a unionized

nursing workforce, following a legal

challenge by the National Labor

Relations Board. ittle Rock’s health care market continues

to be dominated by ABCBS and Baptist

Health System, and their market positions

are bolstered by a close alliance. Since 1994,

ABCBS and Baptist have had a 50/50 joint

venture in the area’s largest health maintenance

organization (HMO), Health

Advantage HMO, and Baptist provides the

majority of services to members enrolled

in ABCBS’s HMO and PPO products.

The alliance reflects a statewide strategy

on the part of ABCBS to contract exclusively

with regionally dominant hospitals.

Some observers believe that these alliances

offer consumers a high-quality network at

a competitive price. Others say the alliances

inhibit competition and may eventually

lead to higher costs for consumers.

In Little Rock, the ABCBS-Baptist

affiliation has remained a powerful force

in the market, while financial and operational

problems have plagued other plans

and hospitals.

Plan Competition. ABCBS has more than 40 percent of the HMO market share

in Little Rock and close to 60 percent statewide. Much of the plan’s strength,

however, derives from its preferred provider organization (PPO), which has more

than 2.5 times the enrollment of its HMO, or approximately 440,000 enrollees statewide.

ABCBS’s closest HMO competitor

in Little Rock is United Healthcare,

which has a 25 percent share of local

HMO enrollees, but its visibility in the

market appears to be diminishing. Last

year, United combined its Arkansas and

Tennessee plans and moved many operations

to Tennessee, leading some observers

to question whether the plan intends to

remain in the Little Rock market.

Also on questionable footing is Little

Rock’s third-largest HMO, QCA QualChoice

Health Plan, with 19 percent local HMO

market share. Two years ago, this plan,

which is owned by the University of

Arkansas Medical Sciences (UAMS),

Tenet Healthcare Corp., and other equity

partners, was positioning itself to compete

more aggressively with the ABCBS-Baptist

alliance. Now, however, the plan

appears to be financially unstable, and

observers say that it may have been insolvent

at times because of difficulties in meeting

state risk reserve requirements. Whether

QualChoice’s equity partners will provide

additional funding is not known, and

observers suggest that a change for the

plan-perhaps new ownership or, in a

worst-case scenario, dissolution-may be

forthcoming.

Meanwhile, in December 2000,

CIGNA pulled out of the Arkansas HMO

market, affecting approximately 11,000

enrollees (some of whom switched to

CIGNA’s PPO or indemnity products the

plan continues to offer). Although CIGNA

was not a major player in Little Rock when

it exited the market, its departure was significant

in that it decreased the number of

health insurance options available to consumers

and reduced competition.

In all, approximately 40 insurers have

reportedly left the Arkansas market since

1998. Although it is unclear whether all of

these insurers offered health insurance

coverage, most observers agree that health

plan competition has decreased. Besides

CIGNA, other notable health plan exits

during the past two years include American

Investors Life and American Healthcare

Providers, Inc., each of which had close

to 20,000 PPO or HMO enrollees at peak

enrollment. Apart from Blue Cross Blue

Shield of Missouri, which entered the

market with HMO and PPO products,

no new plans have entered the Little Rock

market since 1998. Arkansas’ small size

and relatively rural demographics, along

with the poor health and lower socioeconomic

status of its population, have made

the state a less attractive place for health

plans to enter and operate.

Hospital Competition. Competition also has faltered in Little Rock’s hospital

market, and Baptist has maintained a significant competitive advantage. Although

Baptist’s market share in Little Rock proper is similar to that of its nearest

competitor, St. Vincent’s Health System, Baptist attracts significant additional

volume from referrals from 80 affiliated facilities located throughout the state.

To counter this competitive advantage, St. Vincent’s has invested in NovaSys Health

Network, a statewide provider network created in 1996 that includes 6,000 physicians

and 90 acute care hospitals. Despite its arrangement with NovaSys, St. Vincent’s

has not been as successful as Baptist in attracting referrals from outside the

market.

Moreover, recent financial and

operational problems have eroded the

competitive position of St. Vincent’s.

After providing an infusion of capital,

the Denver-based Catholic Health

Initiatives, which has owned St. Vincent’s

since 1997, curtailed additional support

because of its own financial losses.

Meanwhile, St. Vincent’s has experienced

declining volume in cardiac surgery following

the pullout of a major cardiology group

in 1997 that left to form the Arkansas

Heart Hospital. Additionally, St. Vincent’s

1998 acquisition of another local hospital

has reportedly further strained its

finances. At the same time, St. Vincent’s

has experienced staff reductions and

multiple changes in executive management

over the past two years, and, in

June 2000, it became the first private

Arkansas hospital with a unionized

nursing workforce, following a legal

challenge by the National Labor

Relations Board.

Expanded Specialty Care Capacity Threatens Hospital Revenue

ew service capacity in Little Rock and

outlying communities threatens hospitals

with reduced patient volume in tertiary

care and other lucrative services. Since

1998, open-heart surgery programs have

opened in two competing hospitals in

Searcy, an area 45 minutes northeast of

Little Rock. Open-heart surgery programs

now exist in several other Arkansas

cities, and some communities are

beginning to add neonatal intensive

care capacity.

Observers expressed concern that

the limited volume associated with these

community programs poses potential

quality problems. They also fear that this

service expansion, coupled with the higher

overhead structure of these outlying hospitals,

will drive up overall health care

costs in the state. Yet another concern is

that Little Rock hospitals’ loss of tertiary

service volume may constrain the hospitals’

ability to cross-subsidize important,

yet less profitable, services.

The expansion of physician-owned

ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs) also

poses a threat to revenues of Little Rock

hospitals. Six new ASCs have opened since

1998, nearly tripling the number of such

facilities in the market. A few of the ASCs

are multispecialty centers, but most are

limited to a single specialty (e.g., orthopedics,

gastroenterology or otolaryngology).

Three of the ASCs are joint ownership

arrangements between physicians and

hospitals, but the others are physician-owned

or, in one case, owned by a national

firm. In addition, physicians are adding

ancillary services in their private offices

or through freestanding diagnostic centers.

Some say that this build-up of ambulatory

care capacity is a response by specialists

to maintain income levels by supplementing

their revenue with facility fees.

For the past several years, inpatient

capacity has continued to increase in

Little Rock. The Arkansas Heart Hospital

opened in 1997, and there has been a

steady increase in the facility’s number

of staffed beds since then. Additionally,

both Baptist and St. Vincent’s have opened

new inpatient facilities in North Little

Rock since 1998. While Baptist’s facility

was a replacement, St. Vincent’s was an

addition. Both facilities opened with fewer

beds than originally planned, perhaps indicating

that the market is reaching its

upper limit of inpatient capacity. ew service capacity in Little Rock and

outlying communities threatens hospitals

with reduced patient volume in tertiary

care and other lucrative services. Since

1998, open-heart surgery programs have

opened in two competing hospitals in

Searcy, an area 45 minutes northeast of

Little Rock. Open-heart surgery programs

now exist in several other Arkansas

cities, and some communities are

beginning to add neonatal intensive

care capacity.

Observers expressed concern that

the limited volume associated with these

community programs poses potential

quality problems. They also fear that this

service expansion, coupled with the higher

overhead structure of these outlying hospitals,

will drive up overall health care

costs in the state. Yet another concern is

that Little Rock hospitals’ loss of tertiary

service volume may constrain the hospitals’

ability to cross-subsidize important,

yet less profitable, services.

The expansion of physician-owned

ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs) also

poses a threat to revenues of Little Rock

hospitals. Six new ASCs have opened since

1998, nearly tripling the number of such

facilities in the market. A few of the ASCs

are multispecialty centers, but most are

limited to a single specialty (e.g., orthopedics,

gastroenterology or otolaryngology).

Three of the ASCs are joint ownership

arrangements between physicians and

hospitals, but the others are physician-owned

or, in one case, owned by a national

firm. In addition, physicians are adding

ancillary services in their private offices

or through freestanding diagnostic centers.

Some say that this build-up of ambulatory

care capacity is a response by specialists

to maintain income levels by supplementing

their revenue with facility fees.

For the past several years, inpatient

capacity has continued to increase in

Little Rock. The Arkansas Heart Hospital

opened in 1997, and there has been a

steady increase in the facility’s number

of staffed beds since then. Additionally,

both Baptist and St. Vincent’s have opened

new inpatient facilities in North Little

Rock since 1998. While Baptist’s facility

was a replacement, St. Vincent’s was an

addition. Both facilities opened with fewer

beds than originally planned, perhaps indicating

that the market is reaching its

upper limit of inpatient capacity.

Premiums Rise as Cost Controls Falter

hatever hopes remained in 1998 that

managed care would help to control

health care costs in Little Rock have

dimmed. For 2001, premium increases of

20 percent or more for commercial products

are commonplace. Plans report that

the premium increases are necessitated in

part by rapid increases in the utilization

of both inpatient and ambulatory care

services in Little Rock-already among

the highest in the country. Since 1998,

for example, plans report that 10 to 20

percent increases in the utilization of

ambulatory care services are not uncommon,

noting that the increases for those

in HMOs are larger than for those in

PPOs. Observers say that plans considering

market entry naively believe they can

reduce utilization, when, in fact, no plan

has been able to do so. Expanded capacity,

the availability of complex procedures

like bone marrow transplants, increased

consumer demand and weak managed

care controls are all said to be contributing

to the higher utilization.

Plans’ ability to control utilization also has been complicated by a 1998 Arkansas

law requiring plans that offered only a fully insured, closed-panel HMO to also

offer a point-of-service (POS), PPO or indemnity option to employers. Plans report

that this law has steered enrollment away from traditional gatekeeper HMO products

toward more loosely managed POs and PPO products.

Contributing further to the market’s

escalating premiums are pressures placed

on plans by physicians to maintain high

payment levels. Plans in Little Rock, although

sometimes failing to pay promptly, have

been generous in their payments to physicians.

Within Little Rock’s predominantly

discounted fee-for-service context, physician

payment rates go up to 150 percent

or more of the Medicare fee schedule.

Some observers believe that high physician

payment rates are necessary to help

physicians subsidize care because of the

relatively low reimbursement received for

the state’s Medicare beneficiaries.

Mirroring the experience in the commercial

sector, managed care’s influence

on public sector programs in Little Rock

has been limited. Arkansas’ Medicaid

program relies on a primary care case-management

model, and state officials

say that there are no plans to move to

a risk-based model. There has been an

attempt to introduce managed care for

the Medicare population, but only 4 percent

of beneficiaries statewide have

enrolled. Observers cite Medicare beneficiaries’

preference for Medigap coverage

and negative media coverage of HMOs

as deterrents to enrollment.

Meanwhile, during the past two years,

premiums for Medicare+Choice have risen

124 percent, and this has been without

including prescription drug coverage in

its benefit package. Following United

Healthcare and CIGNA’s departure from

the Medicare+Choice market in 2000,

only ABCBS’s Health Advantage HMO

participates, leading some to question if

the plan will continue to participate. hatever hopes remained in 1998 that

managed care would help to control

health care costs in Little Rock have

dimmed. For 2001, premium increases of

20 percent or more for commercial products

are commonplace. Plans report that

the premium increases are necessitated in

part by rapid increases in the utilization

of both inpatient and ambulatory care

services in Little Rock-already among

the highest in the country. Since 1998,

for example, plans report that 10 to 20

percent increases in the utilization of

ambulatory care services are not uncommon,

noting that the increases for those

in HMOs are larger than for those in

PPOs. Observers say that plans considering

market entry naively believe they can

reduce utilization, when, in fact, no plan

has been able to do so. Expanded capacity,

the availability of complex procedures

like bone marrow transplants, increased

consumer demand and weak managed

care controls are all said to be contributing

to the higher utilization.

Plans’ ability to control utilization also has been complicated by a 1998 Arkansas

law requiring plans that offered only a fully insured, closed-panel HMO to also

offer a point-of-service (POS), PPO or indemnity option to employers. Plans report

that this law has steered enrollment away from traditional gatekeeper HMO products

toward more loosely managed POs and PPO products.

Contributing further to the market’s

escalating premiums are pressures placed

on plans by physicians to maintain high

payment levels. Plans in Little Rock, although

sometimes failing to pay promptly, have

been generous in their payments to physicians.

Within Little Rock’s predominantly

discounted fee-for-service context, physician

payment rates go up to 150 percent

or more of the Medicare fee schedule.

Some observers believe that high physician

payment rates are necessary to help

physicians subsidize care because of the

relatively low reimbursement received for

the state’s Medicare beneficiaries.

Mirroring the experience in the commercial

sector, managed care’s influence

on public sector programs in Little Rock

has been limited. Arkansas’ Medicaid

program relies on a primary care case-management

model, and state officials

say that there are no plans to move to

a risk-based model. There has been an

attempt to introduce managed care for

the Medicare population, but only 4 percent

of beneficiaries statewide have

enrolled. Observers cite Medicare beneficiaries’

preference for Medigap coverage

and negative media coverage of HMOs

as deterrents to enrollment.

Meanwhile, during the past two years,

premiums for Medicare+Choice have risen

124 percent, and this has been without

including prescription drug coverage in

its benefit package. Following United

Healthcare and CIGNA’s departure from

the Medicare+Choice market in 2000,

only ABCBS’s Health Advantage HMO

participates, leading some to question if

the plan will continue to participate.

Employers Shift Costs

hile they have expressed disappointment

with managed care’s inability to

control costs, employers have not responded

aggressively to rising premiums. Many

large employers have reconfigured their

health benefits by increasing deductibles

and copayments, rather than passing

premium increases along to employees

through increased contributions. With

this strategy, they have essentially shifted

a larger share of the increased costs to

employees who use health services.

A few small employers have responded

to rising premiums by converting their

employees from group to individual coverage

in what observers describe as a form

of defined contribution. Under these

arrangements, the employer provides the

employee with a fixed contribution to help

cover the cost of coverage. The employee

is responsible for all costs beyond the

employer’s fixed contribution and can

choose from among a range of individual

coverage options offered through the

employer that have varying premiums,

deductibles and copayments. Observers

believe several possible future developments

may prompt more employers to

move to some form of defined contribution,

including declining affordability of

health insurance, passage of state mandates

for minimum benefit packages or passage

of federal legislation that increases the

risk of employer liability. hile they have expressed disappointment

with managed care’s inability to

control costs, employers have not responded

aggressively to rising premiums. Many

large employers have reconfigured their

health benefits by increasing deductibles

and copayments, rather than passing

premium increases along to employees

through increased contributions. With

this strategy, they have essentially shifted

a larger share of the increased costs to

employees who use health services.

A few small employers have responded

to rising premiums by converting their

employees from group to individual coverage

in what observers describe as a form

of defined contribution. Under these

arrangements, the employer provides the

employee with a fixed contribution to help

cover the cost of coverage. The employee

is responsible for all costs beyond the

employer’s fixed contribution and can

choose from among a range of individual

coverage options offered through the

employer that have varying premiums,

deductibles and copayments. Observers

believe several possible future developments

may prompt more employers to

move to some form of defined contribution,

including declining affordability of

health insurance, passage of state mandates

for minimum benefit packages or passage

of federal legislation that increases the

risk of employer liability.

Safety Net Struggles

ike most hospitals in Little Rock, the

market’s leading provider of indigent

care, UAMS, has been hard hit by substantial

cuts in Medicare reimbursement

brought about by the Balanced Budget

Act of 1997. An accounting error that

resulted in a controversial write-off

of $113 million in uncollectable patient

accounts also created difficulty for the

hospital, as did its continued ownership

interest in financially troubled

QualChoice.

In 2000, some financial relief for

UAMS came with a $2 million appropriation

from the state’s General Improvement

Fund for indigent care services, but the

one-time cash infusion covers only a fraction

of the $20 to $25 million losses the

hospital incurred in each of the two previous

years. Some express concern about

UAMS’s continuing financial instability,

because-other than the Arkansas Children’s

Hospital and a few free and church-based

clinics that operate with limited hours-

UAMS is the predominant safety net

provider for adults in Little Rock.

The Arkansas Children’s Hospital,

a key Little Rock safety net provider for

children, has fared better financially than

UAMS, in part because of its specialized

pediatric services. The Arkansas Children’s

Hospital has been successful in securing

numerous managed care contracts, including one with ABCBS, and is the plan’s

only HMO in-network hospital in Little

Rock other than Baptist. State efforts,

such as the State Children’s Health

Insurance Program (SCHIP), have

reduced the number of uninsured children

and helped to maintain UAMS’s

financial health.

Arkansas has relied largely on outside

monies such as SCHIP and, more recently,

tobacco settlement funds to finance initiatives

aimed at reducing the 15 percent

of the population who are uninsured. Since

Arkansas’ SCHIP program, ARKids

1st, began in 1997, the program has

enrolled more than 70,000 previously

uninsured children. Many believe that,

despite the state’s continuing high rate

of uninsurance, almost all children now

have the opportunity to obtain some

form of coverage.

Currently, however, the state and

federal governments are embroiled in a

contentious disagreement over regulations

that require all children eligible for

Medicaid to be enrolled in that program

instead of ARKids 1st. The federal government

maintains that Medicaid-eligible

children are entitled to the comparatively

more expansive Medicaid benefit package

than what they would receive through

ARKids 1st. The state, on the other hand,

argues that its current policy boosts the

number of children with some form of

coverage, because it does not carry with it

the stigma that is often associated with

Medicaid. State officials hope that the

Bush administration signals new leeway

for state preferences and, thus, receptiveness

to the state’s position within the

federal government.

In another initiative aimed at reducing

the number of uninsured, Arkansas

voters approved a ballot initiative during

the November 2000 election directing 30

percent of the state’s average annual

tobacco settlement of $62 million ($1.62

billion over 25 years) to expand Medicaid

eligibility for adults. Under the expansion,

approximately 40,000 additional adults

could become eligible for Medicaid. ike most hospitals in Little Rock, the

market’s leading provider of indigent

care, UAMS, has been hard hit by substantial

cuts in Medicare reimbursement

brought about by the Balanced Budget

Act of 1997. An accounting error that

resulted in a controversial write-off

of $113 million in uncollectable patient

accounts also created difficulty for the

hospital, as did its continued ownership

interest in financially troubled

QualChoice.

In 2000, some financial relief for

UAMS came with a $2 million appropriation

from the state’s General Improvement

Fund for indigent care services, but the

one-time cash infusion covers only a fraction

of the $20 to $25 million losses the

hospital incurred in each of the two previous

years. Some express concern about

UAMS’s continuing financial instability,

because-other than the Arkansas Children’s

Hospital and a few free and church-based

clinics that operate with limited hours-

UAMS is the predominant safety net

provider for adults in Little Rock.

The Arkansas Children’s Hospital,

a key Little Rock safety net provider for

children, has fared better financially than

UAMS, in part because of its specialized

pediatric services. The Arkansas Children’s

Hospital has been successful in securing

numerous managed care contracts, including one with ABCBS, and is the plan’s

only HMO in-network hospital in Little

Rock other than Baptist. State efforts,

such as the State Children’s Health

Insurance Program (SCHIP), have

reduced the number of uninsured children

and helped to maintain UAMS’s

financial health.

Arkansas has relied largely on outside

monies such as SCHIP and, more recently,

tobacco settlement funds to finance initiatives

aimed at reducing the 15 percent

of the population who are uninsured. Since

Arkansas’ SCHIP program, ARKids

1st, began in 1997, the program has

enrolled more than 70,000 previously

uninsured children. Many believe that,

despite the state’s continuing high rate

of uninsurance, almost all children now

have the opportunity to obtain some

form of coverage.

Currently, however, the state and

federal governments are embroiled in a

contentious disagreement over regulations

that require all children eligible for

Medicaid to be enrolled in that program

instead of ARKids 1st. The federal government

maintains that Medicaid-eligible

children are entitled to the comparatively

more expansive Medicaid benefit package

than what they would receive through

ARKids 1st. The state, on the other hand,

argues that its current policy boosts the

number of children with some form of

coverage, because it does not carry with it

the stigma that is often associated with

Medicaid. State officials hope that the

Bush administration signals new leeway

for state preferences and, thus, receptiveness

to the state’s position within the

federal government.

In another initiative aimed at reducing

the number of uninsured, Arkansas

voters approved a ballot initiative during

the November 2000 election directing 30

percent of the state’s average annual

tobacco settlement of $62 million ($1.62

billion over 25 years) to expand Medicaid

eligibility for adults. Under the expansion,

approximately 40,000 additional adults

could become eligible for Medicaid.

Issues to Track

BCBS and Baptist individually and

together, through their alliance, continue

to dominate the Little Rock health care

market, gaining strength as competition

weakens in both the hospital and health

plan sectors. Meanwhile, hospitals are

faced with a different type of threat as

they increasingly confront hospitals in

outlying communities and local physicians

vying for key lucrative services that

were once the exclusive domain of Little

Rock hospitals. These expansions appear

to encourage increased utilization at a

time of slack cost controls in the market.

Double-digit premium increases have

become pervasive, and employers have

begun to respond by shifting more costs

to employees, particularly those using

health services. As costs continue to rise,

many have voiced concern that uninsurance

rates may begin to increase, placing

further strain on an already fragile safety net.

As the health care system in Little

Rock evolves, the following issues will be

important to track: BCBS and Baptist individually and

together, through their alliance, continue

to dominate the Little Rock health care

market, gaining strength as competition

weakens in both the hospital and health

plan sectors. Meanwhile, hospitals are

faced with a different type of threat as

they increasingly confront hospitals in

outlying communities and local physicians

vying for key lucrative services that

were once the exclusive domain of Little

Rock hospitals. These expansions appear

to encourage increased utilization at a

time of slack cost controls in the market.

Double-digit premium increases have

become pervasive, and employers have

begun to respond by shifting more costs

to employees, particularly those using

health services. As costs continue to rise,

many have voiced concern that uninsurance

rates may begin to increase, placing

further strain on an already fragile safety net.

As the health care system in Little

Rock evolves, the following issues will be

important to track:

-

Will greater competition emerge in

Little Rock’s health plan and hospital

markets? What market-driven or regulatory

actions will need to be taken for

this to occur?

- How will the development of tertiary

care services in outlying communities

and the build-up of ambulatory care

capacity by Little Rock’s physicians

affect hospitals’ service volume and

financial viability? Will any steps be

taken to control the market’s capacity

and service expansions?

- Will defined-contribution approaches

gain an additional foothold in the market?

In what other ways will employers

respond to rising premiums? Will premium

increases contribute to a higher

rate of uninsurance?

- How will access to care for the uninsured

be affected by initiatives like

ARKids 1st and Medicaid expansion?

What impact will these initiatives have

on the safety net?

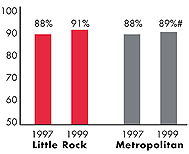

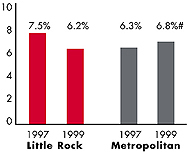

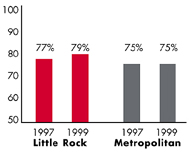

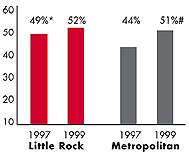

Little Rock’s Experience with the Local Health System, 1997

and 1999

Background and Observations

| Little Rock Demographics |

| Little Rock |

Metropolitan areas above 200,000 population |

Population, July 1, 19991

579,795 |

| Population Change, 1990-19992

|

| 8.4% |

8.6% |

| Median Income3 |

| $28,550 |

$27,843 |

| Persons Living in Poverty3 |

| 12% |

14% |

| Persons Age 65 or Older3 |

| 12% |

11% |

Sources:

1. US Bureau of Census, 1999 Community Population Estimates

2. US Bureau of Census, 1990 & 1999 Community Population Estimates

3. Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1998-1999 |

| Health Insurance Status |

| Little Rock |

Metropolitan areas above 200,000 population |

| Persons under Age 65 with No Health Insurance1 |

| 15% |

15% |

| Children under Age 18 with No Health Insurance1

|

| 12% |

11% |

| Employees Working for Private Firms that

Offer Coverage2 |

| 82% |

84% |

| Average Monthly Premium for Self-Only Coverage

under Employer-Sponsored Insurance2 |

| $158 |

$181 |

Sources:

1. Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1998-1999

2. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Employer Health Insurance Survey, 1997 |

| Health System Characteristics |

| Little Rock |

Metropolitan areas above 200,000 population |

| Staffed Hospital Beds per 1,000 Population1

|

| 5.0 |

2.8 |

| Physicians per 1,000 Population2

|

| 3.1 |

2.3 |

| HMO Penetration, 19973 |

| 25% |

32% |

| HMO Penetration, 19994 |

| 28% |

36% |

Sources:

1. American Hospital Association, 1998

2. Area Resource File, 1998 (includes nonfederal, patient care physicians,

except radiologists, pathologists and anesthesiologists)

3. InterStudy Competitive Edge 8.1

4. InterStudy Competitive Edge 10.1 |

The Community Tracking Study, the major effort of the Center for Studying Health

System Change (HSC), tracks changes in the health system in 60 sites that are

representative of the nation. Every two years, HSC conducts surveys in all 60

communities and site visits in 12 communities. The Community Report series documents

the findings from the third round of site visits. Analyses based on site visit

and survey data from the Community Tracking Study are published by HSC in Issue

Briefs, Data Bulletins and peer-reviewed journals. These publications are

available at www.hschange.org.

Authors of the Little Rock Community Report:

Debra A. Draper, Mathematica Policy Research, Inc.

Linda R. Brewster, HSC

Lawrence D. Brown, Columbia University

Lance Heineccius, University of Washington

Carolyn A. Watts, University of Washington

Laurie E. Felland, HSC

Elizabeth Egan, HSC

Community Reports are published by HSC:

President: Paul B. Ginsburg

Director of Site Visits: Cara S. Lesser

Director of Public Affairs: Ann C. Greiner

Editor: The Stein Group

|