Insurance Coverage & Costs

Access to Care

Quality & Care Delivery

Health Care Markets

Employers/Consumers

Health Plans

Hospitals

Physicians

Insurance Coverage & Costs

Access to Care

Quality & Care Delivery

Health Care Markets

Employers/Consumers

Health Plans

Hospitals

Physicians

Issue Briefs

Data Bulletins

Research Briefs

Policy Analyses

Community Reports

Journal Articles

Other Publications

Surveys

Site Visits

Design and Methods

Data Files

|

Hospitals Profit from Aggressive Negotiations

Miami, Fla.

Community Report No. 10

Summer 2001

Glen P. Mays, Sally Trude, Lawrence P. Casalino, Patricia Lichiello, Ashley C. Short, Andrea Staiti

n February 2001, a team of

researchers visited Miami, Fla., to

study that community’s health system,

how it is changing and the effects

of those changes on consumers. The

Center for Studying Health System

Change (HSC), as part of the

Community Tracking Study, interviewed

more than 70 leaders in the

health care market. Miami is one of

12 communities tracked by HSC

every two years through site visits and

surveys. Individual community

reports are published for each round

of site visits. The first two site visits to

Miami, in 1996 and 1998, provided

baseline and initial trend information

against which changes are

tracked. The Miami community

encompasses Dade County. n February 2001, a team of

researchers visited Miami, Fla., to

study that community’s health system,

how it is changing and the effects

of those changes on consumers. The

Center for Studying Health System

Change (HSC), as part of the

Community Tracking Study, interviewed

more than 70 leaders in the

health care market. Miami is one of

12 communities tracked by HSC

every two years through site visits and

surveys. Individual community

reports are published for each round

of site visits. The first two site visits to

Miami, in 1996 and 1998, provided

baseline and initial trend information

against which changes are

tracked. The Miami community

encompasses Dade County.

The Miami health care market has become more tumultuous

over the past two years, as key hospitals pressed

health plans for more profitable contracts and, in some

cases, threatened to drop out of plan networks if their

demands were not met. Health maintenance organizations

(HMOs), which dominate the market, experienced financial

losses, leading plans to abandon aggressive price

competition and increase premiums, hitting small businesses

especially hard. Meanwhile, in a market where one

in four persons is uninsured, demand for indigent care

has grown. Though safety net providers have taken steps

to respond, a state health care budget shortfall has created

uncertainty about future funding.

Other important developments in Miami since 1998

include:

- Hospital systems dissolved physician ventures and

abandoned risk contracting because of disappointing

financial performance.

- Health plans introduced less restrictive but costlier

products and retooled provider contracting strategies.

- Affordable insurance options for small businesses eroded,

as the state struggled with insurance reform.

Hospitals Gain Clout

trengthened by consolidation during the

1990s, Miami’s hospitals have adopted a

tougher negotiating stance with health plans

and have secured payment increases of 15

percent or more over the past year. Two of

the area’s most prominent hospital systems-

Baptist Health System of South Florida and

HCA-The Healthcare Company-publicly

threatened not to renew contracts with

the state’s largest insurer, Blue Cross and

Blue Shield of Florida, unless their

demands for higher payment rates were

met. HCA did the same with two other

large insurers. Most health plans have

yielded to the hospitals’ demands to keep

provider networks intact.

Hospitals reportedly have sought

higher payments from health plans for

several reasons-among them Medicare

payment reductions resulting from the 1997

Balanced Budget Act (BBA), persistently low

payment rates from commercial health plans,

rising uncompensated care expenditures

and losses on risk contracts and business

ventures with physician organizations. In

seeking higher payments, several hospital

systems have benefited from previous

acquisitions and mergers that gave them

considerable influence in geographically

and demographically distinct market niches

within Miami-Dade County. By establishing

these niches, hospital systems such as

Baptist Health System and Tenet Health

System of South Florida have positioned

themselves as highly desirable components

of health plan networks. Hospitals have

gained additional negotiating leverage as

excess capacity has declined in the area due

to continued population growth, hospital

staffing shortages and problems in the state’s

long-term care industry that have reduced

the availability of nursing home beds for

hospitalized patients awaiting discharge.

Miami’s hospital systems also have

used their leverage to abandon unprofitable

risk contracts and to establish more

favorable contracting terms with health

plans. Since 1998, increasing numbers of

hospitals have moved to lucrative per diem

payment arrangements-often with favorable

stop-loss provisions that give a hospital

added financial protection against high-cost

cases. Furthermore, some hospital systems

have convinced plans to discontinue retroactive

denials, a change reinforced by new

state legislation limiting this practice. In

addition, some hospital systems have

successfully prevented plans from excluding

affiliated hospitals from their networks.

As a result of these changes, as well as

steps to strengthen profitable acute care

and specialty service lines, all four of Miami’s

major hospital systems were profitable as of

2001, with both nonprofit Baptist Health

System and county-owned Jackson Memorial

Hospital rebounding from operating losses

in 1999. Some observers indicated that this

success has enabled hospitals to become

more selective in the types of health plans

and contracting arrangements they will

accept. Nevertheless, some health plans

expected that recent improvements in hospital

profitability would ultimately make

contracting negotiations between hospitals

and plans less contentious. trengthened by consolidation during the

1990s, Miami’s hospitals have adopted a

tougher negotiating stance with health plans

and have secured payment increases of 15

percent or more over the past year. Two of

the area’s most prominent hospital systems-

Baptist Health System of South Florida and

HCA-The Healthcare Company-publicly

threatened not to renew contracts with

the state’s largest insurer, Blue Cross and

Blue Shield of Florida, unless their

demands for higher payment rates were

met. HCA did the same with two other

large insurers. Most health plans have

yielded to the hospitals’ demands to keep

provider networks intact.

Hospitals reportedly have sought

higher payments from health plans for

several reasons-among them Medicare

payment reductions resulting from the 1997

Balanced Budget Act (BBA), persistently low

payment rates from commercial health plans,

rising uncompensated care expenditures

and losses on risk contracts and business

ventures with physician organizations. In

seeking higher payments, several hospital

systems have benefited from previous

acquisitions and mergers that gave them

considerable influence in geographically

and demographically distinct market niches

within Miami-Dade County. By establishing

these niches, hospital systems such as

Baptist Health System and Tenet Health

System of South Florida have positioned

themselves as highly desirable components

of health plan networks. Hospitals have

gained additional negotiating leverage as

excess capacity has declined in the area due

to continued population growth, hospital

staffing shortages and problems in the state’s

long-term care industry that have reduced

the availability of nursing home beds for

hospitalized patients awaiting discharge.

Miami’s hospital systems also have

used their leverage to abandon unprofitable

risk contracts and to establish more

favorable contracting terms with health

plans. Since 1998, increasing numbers of

hospitals have moved to lucrative per diem

payment arrangements-often with favorable

stop-loss provisions that give a hospital

added financial protection against high-cost

cases. Furthermore, some hospital systems

have convinced plans to discontinue retroactive

denials, a change reinforced by new

state legislation limiting this practice. In

addition, some hospital systems have

successfully prevented plans from excluding

affiliated hospitals from their networks.

As a result of these changes, as well as

steps to strengthen profitable acute care

and specialty service lines, all four of Miami’s

major hospital systems were profitable as of

2001, with both nonprofit Baptist Health

System and county-owned Jackson Memorial

Hospital rebounding from operating losses

in 1999. Some observers indicated that this

success has enabled hospitals to become

more selective in the types of health plans

and contracting arrangements they will

accept. Nevertheless, some health plans

expected that recent improvements in hospital

profitability would ultimately make

contracting negotiations between hospitals

and plans less contentious.

Back to Top

Few Physician Contracting

Organizations Remain

ith a few notable exceptions, physician

contracting organizations have failed to

survive in Miami. Numerous national

physician practice management companies

had entered the market, and management

service organizations (MSOs) had formed

to manage physicians’ risk contracts

with health plans. Hospitals had developed

physician-hospital organizations

and employed primary care physicians to

manage risk contracts and protect referrals.

However, most of these ventures

quickly proved financially unsuccessful

and were abandoned.

The demise of physician practice management

companies and hospital-physician

ventures in Miami has soured many physicians

on joining groups, and a steady erosion

of risk contracting has left physicians with

fewer reasons to organize. Most physicians

in the area continue to practice solo or in

small partnerships. A few small single-specialty

physician contracting organizations-

including obstetric/gynecological,

anesthesiology and oncology networks-

have survived and gained some leverage

with health plans, but they are notable

exceptions. These organizations have

secured leverage by controlling large shares

of patient volume at specific hospitals or in

specific geographic areas.

As a result of oversupply and lack of

many contracting organizations, physicians

continue to receive low payment rates. For

privately insured patients in HMOs, physicians

often receive 70 to 80 percent of the

Medicare fee schedule. Although their payment

rates have risen modestly over the

past two years, most Miami physicians have

not secured payment increases comparable

to those won by hospitals.

A few single-specialty physician

organizations have succeeded in creating

ambulatory surgery and diagnostic centers

that compete with hospitals for these

services. But because of hospitals’ opposition

and lingering concerns about the

quality of ambulatory centers, many

health plans have been reluctant to

contract with these centers. ith a few notable exceptions, physician

contracting organizations have failed to

survive in Miami. Numerous national

physician practice management companies

had entered the market, and management

service organizations (MSOs) had formed

to manage physicians’ risk contracts

with health plans. Hospitals had developed

physician-hospital organizations

and employed primary care physicians to

manage risk contracts and protect referrals.

However, most of these ventures

quickly proved financially unsuccessful

and were abandoned.

The demise of physician practice management

companies and hospital-physician

ventures in Miami has soured many physicians

on joining groups, and a steady erosion

of risk contracting has left physicians with

fewer reasons to organize. Most physicians

in the area continue to practice solo or in

small partnerships. A few small single-specialty

physician contracting organizations-

including obstetric/gynecological,

anesthesiology and oncology networks-

have survived and gained some leverage

with health plans, but they are notable

exceptions. These organizations have

secured leverage by controlling large shares

of patient volume at specific hospitals or in

specific geographic areas.

As a result of oversupply and lack of

many contracting organizations, physicians

continue to receive low payment rates. For

privately insured patients in HMOs, physicians

often receive 70 to 80 percent of the

Medicare fee schedule. Although their payment

rates have risen modestly over the

past two years, most Miami physicians have

not secured payment increases comparable

to those won by hospitals.

A few single-specialty physician

organizations have succeeded in creating

ambulatory surgery and diagnostic centers

that compete with hospitals for these

services. But because of hospitals’ opposition

and lingering concerns about the

quality of ambulatory centers, many

health plans have been reluctant to

contract with these centers.

Back to Top

HMO Losses Prompt Changes

arge financial losses have forced health

plans to abandon aggressive price competition

and seek profitability and growth

through changes in product design. Plans

held premiums low through much of the

1990s, despite rising medical care costs, to

gain a foothold in Miami’s oversaturated

HMO market. As a result, annual HMO

losses mounted, peaking at $183 million

statewide in 1999. Since then, several financially

troubled plans dissolved or were

acquired by other plans, but the market has

remained highly competitive, with at least

16 plans operating in Miami.

Consistent with the insurance underwriting

cycle, most plans have raised

premiums substantially over the past year

to compensate for prior-year losses. Annual

premium increases range from 10 percent

for large groups to well over 20 percent for

groups with fewer than 50 employees. To

minimize premium increases, some plans

have moved to reduce utilization and

costs-including reducing provider networks,

strengthening utilization management,

using hospitalists to manage inpatient care

and increasing consumer cost sharing-

despite the objections of some providers

and consumers.

Other plans have sought to increase

profitability and market share by offering

less restrictive health insurance products

as alternatives to traditional gatekeeper

HMOs that have dominated the market.

UnitedHealthcare became Miami’s largest

and fastest-growing HMO-overtaking

plans such as Blue Cross and Blue Shield of

Florida, Humana Medical Plan and AvMed

Health Plan-after introducing a direct-access

HMO product in late 1998. That

United’s enrollment has continued to grow

over the past year-even though premiums

for direct-access products have become

much higher than those for gatekeeper

HMOs-demonstrates the willingness of

many purchasers and consumers to pay

more for less restrictive products.

Several other Miami plans have recently

introduced direct-access products in

response to United’s success.

The growing popularity of direct-access

HMOs has contributed to the

movement away from risk contracting in

Miami because they do not tie patients

and payments to a specific physician or

medical group. Some primary care physicians

reportedly have opposed the move

away from capitation, arguing that discounted

fee-for-service payments are insufficient

to support the full scope of services

formerly provided under capitation.

Historically, Miami’s HMOs relied

either on full-risk contracting with

provider organizations or on primary care

capitation contracts with individual physicians.

Since 1998, however, most hospitals

have discontinued risk-bearing contracts

and have negotiated more lucrative per

diem payments from health plans. Health

plans have retained some risk contracts

with nonhospital-based provider organizations

(such as MSOs) and most capitated

contracts with primary care physicians,

but, according to several health plans, levels

of service have begun to erode under these

arrangements. Consequently, some of the

market’s largest plans have begun to

move back to fee-for-service payment

arrangements with primary care physicians

and to experiment with limited-risk

arrangements (e.g., contact capitation)

for specialists.

Medicare has remained a competitive

and lucrative business line for Miami’s

HMOs, but the generosity of benefits

offered to Medicare beneficiaries has

begun to erode over the past year. The

BBA constrained payment levels and

introduced stricter accounting rules for

Medicare+Choice, causing HMOs’ financial

margins to decline. Nonetheless,

Medicare+Choice payment rates in

Miami have remained among the highest

in the nation because they are based on

the area’s historically high per-capita

Medicare expenditures.

Consequently, Miami’s seniors continue

to pay no premiums for these plans

and to enjoy a broader choice of plans

and a more comprehensive set of benefits

than their counterparts in other markets.

Over the past year, however, several plans

implemented caps on pharmacy benefits

for the first time, and some plans added

or raised copayments for selected services.

Health plans predicted more severe benefit

reductions and the possibility of plan

withdrawals over the next two years if

Medicare+Choice payment increases continue

to lag behind the rates of growth in

medical and pharmaceutical costs. arge financial losses have forced health

plans to abandon aggressive price competition

and seek profitability and growth

through changes in product design. Plans

held premiums low through much of the

1990s, despite rising medical care costs, to

gain a foothold in Miami’s oversaturated

HMO market. As a result, annual HMO

losses mounted, peaking at $183 million

statewide in 1999. Since then, several financially

troubled plans dissolved or were

acquired by other plans, but the market has

remained highly competitive, with at least

16 plans operating in Miami.

Consistent with the insurance underwriting

cycle, most plans have raised

premiums substantially over the past year

to compensate for prior-year losses. Annual

premium increases range from 10 percent

for large groups to well over 20 percent for

groups with fewer than 50 employees. To

minimize premium increases, some plans

have moved to reduce utilization and

costs-including reducing provider networks,

strengthening utilization management,

using hospitalists to manage inpatient care

and increasing consumer cost sharing-

despite the objections of some providers

and consumers.

Other plans have sought to increase

profitability and market share by offering

less restrictive health insurance products

as alternatives to traditional gatekeeper

HMOs that have dominated the market.

UnitedHealthcare became Miami’s largest

and fastest-growing HMO-overtaking

plans such as Blue Cross and Blue Shield of

Florida, Humana Medical Plan and AvMed

Health Plan-after introducing a direct-access

HMO product in late 1998. That

United’s enrollment has continued to grow

over the past year-even though premiums

for direct-access products have become

much higher than those for gatekeeper

HMOs-demonstrates the willingness of

many purchasers and consumers to pay

more for less restrictive products.

Several other Miami plans have recently

introduced direct-access products in

response to United’s success.

The growing popularity of direct-access

HMOs has contributed to the

movement away from risk contracting in

Miami because they do not tie patients

and payments to a specific physician or

medical group. Some primary care physicians

reportedly have opposed the move

away from capitation, arguing that discounted

fee-for-service payments are insufficient

to support the full scope of services

formerly provided under capitation.

Historically, Miami’s HMOs relied

either on full-risk contracting with

provider organizations or on primary care

capitation contracts with individual physicians.

Since 1998, however, most hospitals

have discontinued risk-bearing contracts

and have negotiated more lucrative per

diem payments from health plans. Health

plans have retained some risk contracts

with nonhospital-based provider organizations

(such as MSOs) and most capitated

contracts with primary care physicians,

but, according to several health plans, levels

of service have begun to erode under these

arrangements. Consequently, some of the

market’s largest plans have begun to

move back to fee-for-service payment

arrangements with primary care physicians

and to experiment with limited-risk

arrangements (e.g., contact capitation)

for specialists.

Medicare has remained a competitive

and lucrative business line for Miami’s

HMOs, but the generosity of benefits

offered to Medicare beneficiaries has

begun to erode over the past year. The

BBA constrained payment levels and

introduced stricter accounting rules for

Medicare+Choice, causing HMOs’ financial

margins to decline. Nonetheless,

Medicare+Choice payment rates in

Miami have remained among the highest

in the nation because they are based on

the area’s historically high per-capita

Medicare expenditures.

Consequently, Miami’s seniors continue

to pay no premiums for these plans

and to enjoy a broader choice of plans

and a more comprehensive set of benefits

than their counterparts in other markets.

Over the past year, however, several plans

implemented caps on pharmacy benefits

for the first time, and some plans added

or raised copayments for selected services.

Health plans predicted more severe benefit

reductions and the possibility of plan

withdrawals over the next two years if

Medicare+Choice payment increases continue

to lag behind the rates of growth in

medical and pharmaceutical costs.

Back to Top

Reforms Fail to Prop Up

Small Group Market

ffordable insurance options for Miami’s

smallest businesses have dwindled over the

past two years, despite several recent state

reform efforts. In 1996, Florida attempted

to expand insurance options for small

businesses of up to 50 people, including

sole proprietors, through legislation that

required guaranteed issue (plans offering

insurance must sell to any purchaser)

and community rating (premiums reflect

average health care costs in the community

rather than group characteristics

and costs).

These reforms, which were expected

to lower insurance costs by creating an

influx of healthy people to the state’s

small group insurance market, instead

triggered adverse selection by attracting

people with significant health care needs.

Faced with rising costs from small group

policies, health plans responded by raising

small group premiums significantly,

pulling out of the market altogether or

limiting exposure to small groups. Some

plans have begun using complex enrollment

processes and eliminating broker

commissions to avoid groups of fewer

than 10 people.

Another state initiative created insurance

purchasing associations to make small

group insurance more affordable, but they

were dissolved in 2000 after several years of

unsuccessful operations. This effort, launched

in 1994, created insurance purchasing associations,

called Community Health Purchasing

Alliances (CHPAs), in 11 districts throughout

Florida. The CHPAs lost an important

political advocate with the 1998 death of

Gov. Lawton Chiles, who reportedly used

his clout to encourage health plan participation.

Before Chiles’ death, the Miami-Dade

CHPA had as many as 21 health

plan offerings, but by April 2000, only

two plans remained. Other reasons cited

for the CHPAs’ failure included: ffordable insurance options for Miami’s

smallest businesses have dwindled over the

past two years, despite several recent state

reform efforts. In 1996, Florida attempted

to expand insurance options for small

businesses of up to 50 people, including

sole proprietors, through legislation that

required guaranteed issue (plans offering

insurance must sell to any purchaser)

and community rating (premiums reflect

average health care costs in the community

rather than group characteristics

and costs).

These reforms, which were expected

to lower insurance costs by creating an

influx of healthy people to the state’s

small group insurance market, instead

triggered adverse selection by attracting

people with significant health care needs.

Faced with rising costs from small group

policies, health plans responded by raising

small group premiums significantly,

pulling out of the market altogether or

limiting exposure to small groups. Some

plans have begun using complex enrollment

processes and eliminating broker

commissions to avoid groups of fewer

than 10 people.

Another state initiative created insurance

purchasing associations to make small

group insurance more affordable, but they

were dissolved in 2000 after several years of

unsuccessful operations. This effort, launched

in 1994, created insurance purchasing associations,

called Community Health Purchasing

Alliances (CHPAs), in 11 districts throughout

Florida. The CHPAs lost an important

political advocate with the 1998 death of

Gov. Lawton Chiles, who reportedly used

his clout to encourage health plan participation.

Before Chiles’ death, the Miami-Dade

CHPA had as many as 21 health

plan offerings, but by April 2000, only

two plans remained. Other reasons cited

for the CHPAs’ failure included:

- lack of authority to negotiate with health

plans over product offerings;

- inability to pool members under a single

master contract;

- adverse selection stemming from too

many plan choices for employees;

- opposition from insurance brokers; and

- administrative problems, including lax

standards for screening out individuals

representing themselves as businesses.

A new Florida law intended to bolster

the small group insurance market allows

plans to establish premiums based on age

and sex and then adjust these premiums

based on health status and prior utilization

within a rate band of 15 percent. To

address adverse selection problems, the law

establishes an enrollment period for one-person

businesses. In addition, it provides

a structure for private nonprofit purchasing

alliances that would have the authority

to combine lives from multiple small businesses

under a single master policy. The

law’s impact remains to be seen.

Back to Top

Safety Net Responds to

Growing Demand for Care

ontinued population growth has fueled

the demand for charity care, causing hospitals,

community health centers (CHCs)

and other safety net providers to experience

significant increases in uninsured

caseloads. Miami hospitals have been

particularly hard hit, reporting double-digit

increases in uninsured patients

and uncompensated care costs for 1999.

Miami’s largest charity care provider is

Jackson Memorial Hospital, the only hospital

to receive support from two county-funded

indigent care subsidies. The subsidies-one

funded from general county revenues and

the other through a special state-authorized

sales tax-are administered by the Public

Health Trust of Miami-Dade County, an

independent governing board for county

health services. Other local hospitals have

sought a share of the funding, arguing that

indigent care money should follow uninsured

patients wherever they seek care in

the county, particularly since residents in

some areas do not have easy access to

Jackson Memorial facilities.

The Florida Legislature weighed in on

the controversy in 2000 by passing a law

requiring Miami-Dade County to use

some of its indigent care dollars to operate

a county-wide plan for the uninsured.

Asserting that the law violated the county’s

home rule authority, the Miami-Dade

County Commission refused to implement

it. In February 2001, seven local hospitals

filed a suit against the county seeking to

force compliance with the new law, creating

continued uncertainty about the distribution

of Miami’s indigent care funds.

In an effort to enhance its position as a countywide source of care, Jackson Memorial

Hospital-recently renamed Jackson Health System-has strengthened relationships

with several CHCs and has pursued acquisition of a community hospital serving

southern Dade County, an area where Jackson lacks a strong presence. Jackson also

has begun conversations with several community organizations about creating a

pilot managed care plan for the uninsured in southern Dade County. Other hospitals

argue that Jackson’s actions fall far short of the intent of the state’s indigent

care legislation.

In the midst of this controversy,

Miami’s CHCs have expanded their infrastructure,

services and hours to address the

growing demand for community-based

charity care. CHCs have obtained funding

for these expansions from various sources,

including the Public Health Trust, local governments

and federal grant programs. They

also have developed contracts with Medicaid

HMOs and strengthened efforts to enroll

uninsured patients in Medicaid and the

state’s umbrella program for children’s health

insurance, Florida KidCare. Several community

advocacy organizations have augmented

CHC efforts by launching intensive out-reach

and education campaigns to increase

access to health care among Miami’s large

uninsured and immigrant populations. ontinued population growth has fueled

the demand for charity care, causing hospitals,

community health centers (CHCs)

and other safety net providers to experience

significant increases in uninsured

caseloads. Miami hospitals have been

particularly hard hit, reporting double-digit

increases in uninsured patients

and uncompensated care costs for 1999.

Miami’s largest charity care provider is

Jackson Memorial Hospital, the only hospital

to receive support from two county-funded

indigent care subsidies. The subsidies-one

funded from general county revenues and

the other through a special state-authorized

sales tax-are administered by the Public

Health Trust of Miami-Dade County, an

independent governing board for county

health services. Other local hospitals have

sought a share of the funding, arguing that

indigent care money should follow uninsured

patients wherever they seek care in

the county, particularly since residents in

some areas do not have easy access to

Jackson Memorial facilities.

The Florida Legislature weighed in on

the controversy in 2000 by passing a law

requiring Miami-Dade County to use

some of its indigent care dollars to operate

a county-wide plan for the uninsured.

Asserting that the law violated the county’s

home rule authority, the Miami-Dade

County Commission refused to implement

it. In February 2001, seven local hospitals

filed a suit against the county seeking to

force compliance with the new law, creating

continued uncertainty about the distribution

of Miami’s indigent care funds.

In an effort to enhance its position as a countywide source of care, Jackson Memorial

Hospital-recently renamed Jackson Health System-has strengthened relationships

with several CHCs and has pursued acquisition of a community hospital serving

southern Dade County, an area where Jackson lacks a strong presence. Jackson also

has begun conversations with several community organizations about creating a

pilot managed care plan for the uninsured in southern Dade County. Other hospitals

argue that Jackson’s actions fall far short of the intent of the state’s indigent

care legislation.

In the midst of this controversy,

Miami’s CHCs have expanded their infrastructure,

services and hours to address the

growing demand for community-based

charity care. CHCs have obtained funding

for these expansions from various sources,

including the Public Health Trust, local governments

and federal grant programs. They

also have developed contracts with Medicaid

HMOs and strengthened efforts to enroll

uninsured patients in Medicaid and the

state’s umbrella program for children’s health

insurance, Florida KidCare. Several community

advocacy organizations have augmented

CHC efforts by launching intensive out-reach

and education campaigns to increase

access to health care among Miami’s large

uninsured and immigrant populations.

Back to Top

KidCare’s Growing Pains

ecent state initiatives to expand public

insurance coverage have helped Miami’s

safety net providers. But the rapid growth

in state health care expenditures has

raised questions about the sustainability

of these efforts. Over the past two years,

Florida has significantly expanded eligibility

for Florida KidCare-an umbrella

program supported through joint federal

and state funding for Medicaid and the

State Children’s Health Insurance Program

(SCHIP), as well as through separate state

appropriations. These eligibility expansions,

combined with a recent outreach campaign,

have netted KidCare nearly 74,000 additional

children in Miami since the beginning of

1999, more than double the 35,000 children

originally expected. The massive

influx of new enrollees, plus rising pharmaceutical

costs, has greatly expanded

Florida’s health care budget.

Mounting state budget pressures have stimulated efforts to control health care

spending. To reduce state expenditures that do not draw down federal matching

funds, the Florida Legislature placed a $13.5 million annual limit on state funding

in 2000 for Florida KidCare enrollees who are ineligible for coverage under federal

Medicaid and SCHIP regulations, including non-citizen children, children of state

employees and 19-year-olds. Florida covers these groups with state appropriations-through

an initiative that predates SCHIP and KidCare-but because of the state funding

limit, enrollment in KidCare was capped for these groups after July 1, 2000. A

waiting list of approximately 6,000 enrollees had formed as of February 2001-with

residents of Miami-Dade and two other south Florida counties reportedly comprising

about 75 percent of those waiting.

While Florida has constrained spending

on individuals ineligible for Medicaid

or SCHIP coverage, state Medicaid expenditures

have continued to grow, resulting

in a Medicaid budget shortfall expected to

total $1 billion by mid-2001, according to

some estimates. This shortfall has generated

a variety of proposals to reduce Medicaid

spending, including payment cuts to

providers and health plans and efforts

to increase Medicaid enrollment in HMOs.

In view of Florida’s mounting budget problems,

some observers feared state efforts to

expand public insurance coverage in

Miami have begun to reach their limits. ecent state initiatives to expand public

insurance coverage have helped Miami’s

safety net providers. But the rapid growth

in state health care expenditures has

raised questions about the sustainability

of these efforts. Over the past two years,

Florida has significantly expanded eligibility

for Florida KidCare-an umbrella

program supported through joint federal

and state funding for Medicaid and the

State Children’s Health Insurance Program

(SCHIP), as well as through separate state

appropriations. These eligibility expansions,

combined with a recent outreach campaign,

have netted KidCare nearly 74,000 additional

children in Miami since the beginning of

1999, more than double the 35,000 children

originally expected. The massive

influx of new enrollees, plus rising pharmaceutical

costs, has greatly expanded

Florida’s health care budget.

Mounting state budget pressures have stimulated efforts to control health care

spending. To reduce state expenditures that do not draw down federal matching

funds, the Florida Legislature placed a $13.5 million annual limit on state funding

in 2000 for Florida KidCare enrollees who are ineligible for coverage under federal

Medicaid and SCHIP regulations, including non-citizen children, children of state

employees and 19-year-olds. Florida covers these groups with state appropriations-through

an initiative that predates SCHIP and KidCare-but because of the state funding

limit, enrollment in KidCare was capped for these groups after July 1, 2000. A

waiting list of approximately 6,000 enrollees had formed as of February 2001-with

residents of Miami-Dade and two other south Florida counties reportedly comprising

about 75 percent of those waiting.

While Florida has constrained spending

on individuals ineligible for Medicaid

or SCHIP coverage, state Medicaid expenditures

have continued to grow, resulting

in a Medicaid budget shortfall expected to

total $1 billion by mid-2001, according to

some estimates. This shortfall has generated

a variety of proposals to reduce Medicaid

spending, including payment cuts to

providers and health plans and efforts

to increase Medicaid enrollment in HMOs.

In view of Florida’s mounting budget problems,

some observers feared state efforts to

expand public insurance coverage in

Miami have begun to reach their limits.

Back to Top

Issues to Track

rowing hospital negotiating power in

Miami, combined with health plans’ decisions

to offer less restrictive and more

expensive products, has heightened concerns

about the affordability of health

insurance for Miami residents. Florida’s

past efforts to make insurance more

affordable for small businesses have failed,

and the state’s recent public insurance

expansions appear vulnerable to budget

difficulties. With one in four people already

uninsured, any erosion in employer-based

or public coverage could stretch the safety

net beyond its limits. Together, these developments

raise new questions about how

health care delivery and health insurance

coverage may change in Miami: rowing hospital negotiating power in

Miami, combined with health plans’ decisions

to offer less restrictive and more

expensive products, has heightened concerns

about the affordability of health

insurance for Miami residents. Florida’s

past efforts to make insurance more

affordable for small businesses have failed,

and the state’s recent public insurance

expansions appear vulnerable to budget

difficulties. With one in four people already

uninsured, any erosion in employer-based

or public coverage could stretch the safety

net beyond its limits. Together, these developments

raise new questions about how

health care delivery and health insurance

coverage may change in Miami:

- Will consumers and employers continue

to move to direct-access products, despite

rising health care costs and premiums?

- How will rising health insurance premiums

affect private health insurance

coverage, especially for small businesses?

- How will Florida’s new small group insurance

reforms affect small employers’

access to affordable coverage?

- How will hospitals, policy makers and the

Public Health Trust resolve the longstanding

controversy over public funding for

indigent care, and what impact will their

decisions have on access to care for the

uninsured?

- How will state budget pressures affect

benefits and coverage under Florida’s

Medicaid and SCHIP expansion programs,

and how will safety net providers

be affected?

Back to Top

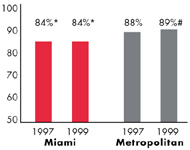

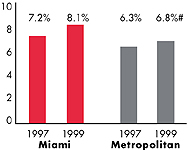

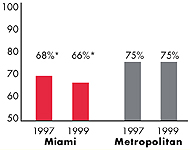

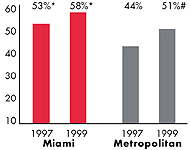

Miami’s Experience with the Local Health System, 1997 and 1999

Back to Top

Background and Observations

| Miami Demographics |

| Miami County |

Metropolitan areas above 200,000 population |

Population, July 1, 19991

2,175,634 |

| Population Change, 1990-19992

|

| 12% |

8.6% |

| Median Income3 |

| $19,672 |

$27,843 |

| Persons Living in Poverty3 |

| 25% |

14% |

| Persons Age 65 or Older3 |

| 15% |

11% |

Sources:

1. US Bureau of Census, 1999 Community Population Estimates

2. US Bureau of Census, 1990 & 1999 Community Population Estimates

3. Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1998-1999 |

| Health Insurance Status |

| Miami |

Metropolitan areas above 200,000 population |

| Persons under Age 65 with No Health Insurance1 |

| 23% |

15% |

| Children under Age 18 with No Health Insurance1

|

| 17% |

11% |

| Employees Working for Private Firms that

Offer Coverage2 |

| 77% |

84% |

| Average Monthly Premium for Self-Only Coverage

under Employer-Sponsored Insurance2 |

| $161 |

$181 |

Sources:

1. Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1998-1999

2. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Employer Health Insurance Survey, 1997 |

| Health System Characteristics |

| Miami |

Metropolitan areas above 200,000 population |

| Staffed Hospital Beds per 1,000 Population1

|

| 3.6 |

2.8 |

| Physicians per 1,000 Population2

|

| 2.7 |

2.3 |

| HMO Penetration, 19973 |

| 64% |

32% |

| HMO Penetration, 19994 |

| 52% |

36% |

Sources:

1. American Hospital Association, 1998

2. Area Resource File, 1998 (includes nonfederal, patient care physicians,

except radiologists, pathologists and anesthesiologists)

3. InterStudy Competitive Edge 8.1

4. InterStudy Competitive Edge 10.1 |

Back to Top

The Community Tracking Study, the major effort of the Center for Studying Health

System Change (HSC), tracks changes in the health system in 60 sites that are

representative of the nation. Every two years, HSC conducts surveys in all 60

communities and site visits in 12 communities. The Community Report series documents

the findings from the third round of site visits. Analyses based on site visit

and survey data from the Community Tracking Study are published by HSC in Issue

Briefs, Data Bulletins and peer-reviewed journals. These publications are

available at www.hschange.org.

Authors of the Miami Community Report:

Glen P. Mays, Mathematica Policy Research, Inc.

Sally Trude, HSC

Lawrence P. Casalino, University of Chicago

Patricia Lichiello, University of Washington

Ashley C. Short, HSC

Andrea Benoit, HSC

Community Reports are published by HSC:

President: Paul B. Ginsburg

Director of Site Visits: Cara S. Lesser

Director of Public Affairs: Ann C. Greiner

Editor: The Stein Group

|