Stand-Alone Health Insurance Tax Credits Aren't Enough

Issue Brief No. 41

July 2001

Leslie A. Jackson, Sally Trude

![]() sing health insurance tax credits to help reduce the ranks of the nearly 43 million

uninsured Americans has attracted broad bipartisan support in Congress. But tax

credits alone will not help many sick or older people obtain affordable coverage,

according to an expert panel at an April 10, 2001, conference sponsored by the

Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC). To make tax credits a viable

option for eligible people, the individual insurance market would need significant

reforms or a better way to spread risk-similar to large employers-over a large

and varied population. This Issue Brief highlights critical issues policy makers should

consider when crafting tax credit proposals, including the use of purchasing pools.

sing health insurance tax credits to help reduce the ranks of the nearly 43 million

uninsured Americans has attracted broad bipartisan support in Congress. But tax

credits alone will not help many sick or older people obtain affordable coverage,

according to an expert panel at an April 10, 2001, conference sponsored by the

Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC). To make tax credits a viable

option for eligible people, the individual insurance market would need significant

reforms or a better way to spread risk-similar to large employers-over a large

and varied population. This Issue Brief highlights critical issues policy makers should

consider when crafting tax credit proposals, including the use of purchasing pools.

Tax Credits Could Help Millions Get Coverage

![]() ecent tax credit proposals to assist lower-income people obtain

health insurance have strong bipartisan congressional support and could help subsidize

insurance costs for millions of Americans. The proposals, however, vary in key

areas, including tax credit amounts, income thresholds and whether people could

use tax credits to pay for employer-sponsored insurance or buy coverage only in

the individual market.

ecent tax credit proposals to assist lower-income people obtain

health insurance have strong bipartisan congressional support and could help subsidize

insurance costs for millions of Americans. The proposals, however, vary in key

areas, including tax credit amounts, income thresholds and whether people could

use tax credits to pay for employer-sponsored insurance or buy coverage only in

the individual market.

For example, the bipartisan Relief, Equity, Access and Coverage for Health (REACH) Act (S. 590) proposes income-based tax credits of $1,000 for individuals and $2,500 for families without access to employer-sponsored insurance, and tax credits of up to $400 for individuals and $1,000 for families eligible for employer-sponsored insurance. REACH sponsors estimate that up to 10 million currently uninsured people could gain coverage under this proposal. In contrast, the Bush Administration’s plan has slightly less generous tax credits and would allow people to purchase coverage in the individual insurance market but not through an employer.

Panelists warned that tax credit proposals relying on the individual insurance market’s current structure would not be as effective as policy makers envision. "I’ve been challenged in the past to name one state in the country where the individual market works well," said panelist Richard E. Curtis, president of the not-for-profit Institute for Health Policy Solutions.

Risk Selection Plagues the Individual Market

![]() ccording to panelists, the individual

market’s major flaw is risk selection, or

whether an insurer attracts a disproportionate

number of sick or healthy

individuals. Insurers compete based

on how accurately they set prices and

determine coverage according to what

is known about an individual’s health

status, with the market rewarding

insurers that manage risk selection

well. If an insurer attracts too many

high-risk people, the cost of coverage

will increase and healthy people will

look for a better deal elsewhere.

ccording to panelists, the individual

market’s major flaw is risk selection, or

whether an insurer attracts a disproportionate

number of sick or healthy

individuals. Insurers compete based

on how accurately they set prices and

determine coverage according to what

is known about an individual’s health

status, with the market rewarding

insurers that manage risk selection

well. If an insurer attracts too many

high-risk people, the cost of coverage

will increase and healthy people will

look for a better deal elsewhere.

To avoid high-risk individuals, insurers may offer policies more attractive to healthier individuals, such as low-premium plans with high deductibles, less comprehensive packages and restricted choice of providers. More often, however, individuals with health problems find that insurers will raise premiums, limit benefits for particular conditions or deny coverage entirely. Indeed, a recent study showed that even individuals with relatively minor health conditions may be considered substandard risks and face higher premiums or restricted benefits.1

The behavior of people buying individual insurance also contributes to risk selection. Individuals have an advantage over insurers because people know more about their health status and what kinds of health services they may need than insurers do, according to John M. Bertko, vice president and chief actuary at Humana, Inc. For example, a person may choose a generous benefit package if planning a pregnancy or elective surgery, and, when health services are no longer needed, either switch to a less comprehensive plan or drop coverage altogether.

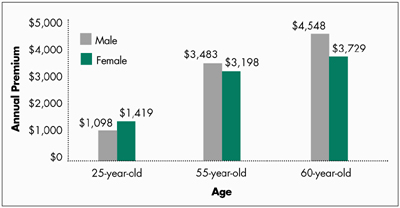

To combat this, insurers offering individual policies underwrite, or set the terms of coverage and premiums, based on a variety of individual factors that vary by state, including a person’s age, sex, health status and geographic location. These underwriting policies result in higher premiums for people who are older or sicker, if they are even offered coverage at all. Age alone can be a significant determinant of an individual’s premium cost in the individual market (see Figure 1).

Some have suggested the individual market would stabilize if more people purchased individual insurance. Tax credits are expected to provide an incentive for more people to purchase insurance and, possibly, retain coverage, rather than dropping it based on medical need. But policy makers would be dissatisfied with the likely result of stand-alone tax credits: while healthy individuals may take advantage of the tax credit and purchase insurance, older and sicker people likely would be cut off from affordable health insurance because of tough individual underwriting.

"Tax credits will go a long way to infusing the individual market with healthy lives, but you still have this incredibly fragmented market, with individuals making health insurance decisions on their own," Curtis said. "By definition, you do not have good risk-spreading capacity."

Panelist Stuart M. Butler, Ph.D., vice president for domestic and economic policy studies at the Heritage Foundation, agreed, saying that tax-credit proponents recognize that an effective policy must combine underwriting restrictions and a method to deal with risk selection. Bertko echoed concerns about sending people with tax credits shopping for insurance without individual market reforms. "My actuarial colleagues who do individual coverage are very good at what they do," he said. "If you have a continuation of the current individual, toughly underwritten, market, the people who do the tough underwriting win, and they always win."

Summarizing the panelists’ views on the current individual market, HSC President Paul B. Ginsburg, Ph.D., said, "Everyone on the panel agrees that today’s individual market does not have the characteristics that you’d want to send 10 million- plus people into with tax credits. One way or another, you would want to set strong rules for this market."

| Figure 1 Impact of Age and Sex in Individual Market: Phoenix, Ariz., as an Example  Note: Initial quotes for nonsmoking individuals for a preferred provider organization with a $500 deductible, $20 office visit copayment and 80/20 coinsurance. Source: www.ehealthinsurance.com on June 2, 2001 |

The Role of Purchasing Pools

![]() ax credits could provide an opportunity to regulate the individual

market aggressively. Alternatively, experts have proposed making tax credits more

effective through purchasing pools, buying into public programs or extending the

Federal Employee Health Benefits Program.2 HSC’s

conference focused on linking purchasing pools to tax credits, building on HSC’s

research on private markets and small business associations.

ax credits could provide an opportunity to regulate the individual

market aggressively. Alternatively, experts have proposed making tax credits more

effective through purchasing pools, buying into public programs or extending the

Federal Employee Health Benefits Program.2 HSC’s

conference focused on linking purchasing pools to tax credits, building on HSC’s

research on private markets and small business associations.

Purchasing pools are designed to mimic large employers, which, as Curtis noted, are natural groups that bring people together based on work, not health status. "Such groups represent a broad spectrum of risks, and it works for insurance purposes," he said. Large employers’ premiums typically are based on the group’s collective risk and claims experience, allowing employees to pay the same premium regardless of age or health status.

Similarly, Curtis said, linking tax credits and purchasing pools would result in a broader spectrum of risk-compared to the current individual market-because it would be based on an individual’s income, not health status. Furthermore, purchasing pools potentially can capture other efficiencies enjoyed by large employers, including aggregated purchasing power and administrative cost savings, according to Mark A. Hall, professor of law and public health at Wake Forest University (see box).

Some panelists were concerned that mandating the use of purchasing pools would stifle innovation. "You can’t say, ’We’ve discovered the Holy Grail. It’s called a purchasing pool, and we want everybody to be in these,’" Butler said. "It would be unwise to impose pools everywhere, because you then will never know if some alternative is a better arrangement."

Hall suggested the 1996 Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) as a model for setting federal standards while allowing state innovation. "HIPAA, in its insurance regulation aspect, has set a reasonably workable model," he said. "It has fairly broad federal standards and has allowed states some diversity in certifying or choosing options or having a default if states don’t respond. Something like this would allow a variety of approaches to emerge across the states, but all oriented toward achieving a general federal objective."

Building on Current Systems

![]() anelists stressed the importance of designing

a tax credit policy to complement existing

coverage sources, such as allowing

employees to use tax credits to buy employer-sponsored

coverage. This may offer the benefit

of purchasing health insurance with pretax

dollars, making coverage more affordable.

Other options include allowing people with

tax credits to buy into public programs, such

as Medicaid or the State Children’s Health

Insurance Program (SCHIP), or combining

public subsidies to make coverage in the

individual market more affordable.

anelists stressed the importance of designing

a tax credit policy to complement existing

coverage sources, such as allowing

employees to use tax credits to buy employer-sponsored

coverage. This may offer the benefit

of purchasing health insurance with pretax

dollars, making coverage more affordable.

Other options include allowing people with

tax credits to buy into public programs, such

as Medicaid or the State Children’s Health

Insurance Program (SCHIP), or combining

public subsidies to make coverage in the

individual market more affordable.

Butler saw advantages in linking tax credits with existing public programs, saying, "One can envision the SCHIP program being converted, for certain people, into a voucher that supplements the federal tax credit, which is getting you very close to real affordability."

Federal policies should not have the unfortunate effect of requiring family members to go to different places to obtain coverage, according to Curtis. "Medical homes logically start at home," he said, adding that allowing families to obtain coverage from just one source avoids having "the 5-year-old kid one place, the 10- year-old kid another place, the mom someplace else, the dad someplace else and, oh, by the way, all of them are going to have to change next year because somebody’s status changed."

Curtis cautioned, however, that expanding access to public programs for individuals with access to employer-sponsored coverage might create incentives for employees to drop coverage because they might end up paying less to buy into the public program. If that’s the case, "people aren’t dumb," he said. "They’ll go to the public program." If this happens, employers’ insurance coverage could be jeopardized, according to Curtis, because if employees decide to use the tax credit elsewhere, then employers may not meet the minimum employee participation thresholds many health plans require.

Debate Over Ways to Make Tax Credits More Effective

![]() he panelists discussed the wisdom of various

approaches, including a tax-credit policy

linked to purchasing pools versus reforms to

the individual market or even leaving a door

open for market innovations to emerge. "The

individual market needs a variety of new

rules, but it might be a hard case to make

that purchasing pools have an inherent

advantage," Bertko said. He agreed, however,

that the individual market might need

substantial reforms to accept tax credits.

Butler also questioned the logic of purchasing

pools, asking, "Are we going to create

yet another system on top of the traditional

employment-based system and the

individual market, segmenting out another

group of people and creating a completely

different system for them?"

he panelists discussed the wisdom of various

approaches, including a tax-credit policy

linked to purchasing pools versus reforms to

the individual market or even leaving a door

open for market innovations to emerge. "The

individual market needs a variety of new

rules, but it might be a hard case to make

that purchasing pools have an inherent

advantage," Bertko said. He agreed, however,

that the individual market might need

substantial reforms to accept tax credits.

Butler also questioned the logic of purchasing

pools, asking, "Are we going to create

yet another system on top of the traditional

employment-based system and the

individual market, segmenting out another

group of people and creating a completely

different system for them?"

Hall countered, "If you compare purchasing pools against shopping with the tax credit in the existing individual market, there’s no question that something like the pools is required. You just can’t give people a tax credit and say, ’Go out to the unregulated, unstructured individual market and good luck.’" Curtis agreed, saying, "A purchasing pool is not identical to a large employer, but it’s a lot closer than the individual market."

While panelists disagreed about what a policy to bolster tax credits should look like, all agreed policy makers must grapple with risk selection if they want to ensure people with health problems can use tax credits to obtain affordable coverage in the individual market. Congress and the Administration have not decided how to increase the effectiveness of tax credits and reduce risk selection. "A consensus has not emerged in Congress on the best approach to this issue," said John McManus, majority staff director of the House Ways and Means health subcommittee. "We’re just at the beginning stages."

Characteristics of a Purchasing Pool Alternative

![]() lthough panelists split on a mandatory policy linking tax

credits to purchasing pools, there was significant agreement about how to design

an effective purchasing pool policy. Based on the assumption that a limited number

of purchasing pools would be authorized by either state or federal governments,

the panelists quickly agreed that an enrollment lock-in would be necessary to

prevent individuals- who will almost always know more about their health status

than insurers- from adding or dropping insurance as needed. Otherwise, insurers

would refuse to participate.

lthough panelists split on a mandatory policy linking tax

credits to purchasing pools, there was significant agreement about how to design

an effective purchasing pool policy. Based on the assumption that a limited number

of purchasing pools would be authorized by either state or federal governments,

the panelists quickly agreed that an enrollment lock-in would be necessary to

prevent individuals- who will almost always know more about their health status

than insurers- from adding or dropping insurance as needed. Otherwise, insurers

would refuse to participate.

Panelists also agreed that allowing small employers to participate in the pool made sense. Curtis summarized panelists’ views by saying, "It would be a win-win to allow workers to use their tax credit in the purchasing pool through their employer. There would be no crowd-out of existing employer contributions in that instance."

Curtis encouraged establishing competing purchasing pools to extend as much choice to people as possible. Panelists agreed that ensuring a choice of plans also was an important benefit of a purchasing-pool option. "Having the ability to offer 10 different health plans to 20 employees was very much of a bonus," Bertko said, referring to his previous experience as a small employer participating in a purchasing pool.

Addressing risk selection and ensuring a level playing field for purchasing pools compared with the rest of the market would be the primary challenges for an effective policy linking tax credits to purchasing pools, including standardizing underwriting rules across the market.

"If individuals with tax credits can move willy-nilly around different pools, going in and out of the pools, and those pools rate people differently, the pools just are not going to work," Curtis said. If people without tax credits can participate in the pool, Curtis also stressed the importance of underwriting these people like the rest of the market; otherwise, the market won’t work. "I hope federal policy makers would not expect purchasing pools to wear the white hat by accepting bad risks on the same basis as good risks, to charge them the same amount, if the rest of the market didn’t have to do that. Inevitably, that does not work; it cannot work."

Finally, the panelists’ opinions varied on what type of entities should be allowed to operate purchasing pools, with the two major options discussed being solely private or a mix of not-for-profit and for-profit organizations. Start-up capital could be a key issue when deciding whether to allow for-profit entities to run purchasing pools. "If you’re not going to provide special funding for startup, then why would you prohibit other organizations and entities from helping to get the purchasing pools off the ground?" Bertko asked. Limiting participation to not-for-profits, however, would help ensure purchasing pools "really are there to represent the best interests of consumers," Curtis said.

This Issue Brief is based on a conference sponsored by HSC on April 10, 2001, in Washington, D.C.

Conference Participants

Overview

Sally Trude

Center for Studying Health

System Change

Panelists

John M. Bertko

Humana, Inc.

Stuart M. Butler

Heritage Foundation

Richard E. Curtis

Institute for Health Policy

Solutions

Mark A. Hall

Wake Forest University

John McManus

House Ways and Means Health

Subcommittee

Philip J. Vogel

Connecticut Business &

Industry Association

Moderator

Paul B. Ginsburg

Center for Studying Health System Change

Notes

| 1. | Pollitz, Karen, Richard Sorian and Kathy Thomas, How Accessible Is Individual Health Insurance for Consumers in Less-than-Perfect Health? Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation (June 2001). |

| 2. | These proposals are described in The Commonwealth Fund’s report series, “Strategies to Expand Insurance for Working Americans.” |

ISSUE BRIEFS are published by the Center for Studying Health System Change.

President: Paul B. Ginsburg

Director of Public Affairs: Ann C. Greiner

Editor: The Stein Group