Insurance Coverage & Costs

Costs

The Uninsured

Private Coverage

Employer Sponsored

Individual

Public Coverage

Medicare

Medicaid and SCHIP

Access to Care

Quality & Care Delivery

Health Care Markets

Insurance Coverage & Costs

Costs

The Uninsured

Private Coverage

Employer Sponsored

Individual

Public Coverage

Medicare

Medicaid and SCHIP

Access to Care

Quality & Care Delivery

Health Care Markets

Issue Briefs

Data Bulletins

Research Briefs

Policy Analyses

Community Reports

Journal Articles

Other Publications

Surveys

Site Visits

Design and Methods

Data Files

|

Financial Woes and Contract Disputes Disrupt Market

Boston, Mass.

Community Report No. 11

Summer 2001

Kelly Devers, Jon B. Christianson, Laurie E. Felland, Suzanne Felt-Lisk, Liza Rudell, Linda R. Brewster, Ha T. Tu

n February 2001, a team of

researchers visited Boston, Mass., to

study that community’s health care

system, how it is changing and the

effects of those changes on consumers.

The Center for Studying Health

System Change (HSC), as part of the

Community Tracking Study, interviewed

more than 95 leaders in the

health care market. Boston is one of

the 12 communities tracked by HSC

every two years through site visits and

surveys. Individual community reports

are published for each round of site

visits. The first two site visits to

Boston, in 1996 and 1998, provided

baseline and initial trend information

against which changes are

tracked. The Boston market includes

the city of Boston and Bristol, Essex,

Middlesex, Norfolk, Plymouth and

Suffolk counties. n February 2001, a team of

researchers visited Boston, Mass., to

study that community’s health care

system, how it is changing and the

effects of those changes on consumers.

The Center for Studying Health

System Change (HSC), as part of the

Community Tracking Study, interviewed

more than 95 leaders in the

health care market. Boston is one of

the 12 communities tracked by HSC

every two years through site visits and

surveys. Individual community reports

are published for each round of site

visits. The first two site visits to

Boston, in 1996 and 1998, provided

baseline and initial trend information

against which changes are

tracked. The Boston market includes

the city of Boston and Bristol, Essex,

Middlesex, Norfolk, Plymouth and

Suffolk counties.

After a period of relative stability, Boston’s health care

market was disrupted over the past two years by financial

difficulties in the plan and hospital sectors and

contentious contract disputes between the largest care

system and local plans. Policy makers rapidly enacted

legislation to stabilize the market and took action to

ensure consumers’ access to health care.

In the interest of helping local, not-for-profit plans

regain their financial footing, employers accepted double-digit

premium increases. Consumers continued to enjoy

relatively rich benefits but faced higher copayments for

prescription drugs and outpatient services. Other

important developments include:

- Health maintenance organizations (HMOs) continued

to dominate the plan market but were beginning

to change considerably as plans and providers shed

risk contracts and explored new products and payment

arrangements.

- A state ballot initiative for universal health care

coverage was narrowly defeated, but it prompted the

Massachusetts Legislature to pass a long-debated

patients’ bill of rights.

- Safety net providers, with strong state support and

sound management, remained relatively stable.

Plans and Community Hospitals Experience Financial Distress

t the time of HSC’s 1998 site visit, Boston’s health care

market had reached relative equilibrium after multiple mergers and acquisitions

left the market consolidated largely around three locally operated, not-for-profit

health plans and two large academic medical center (AMC)-based provider systems.

Since then, a series of events has upset the fragile balance among these organizations,

threatening disruptions for consumers and prompting policy makers to intervene.

Leading Plans Falter. Two local, not-for-profit health plans with national

reputations as pioneering, high-quality HMOs-Harvard Pilgrim Health Care (HPHC)

and Tufts Health Plan-experienced serious financial problems. Both HPHC and Tufts

have long been a source of local pride. Their local roots and not-for- profit

status have been important features in the eyes of policy makers and local providers,

who have been wary of national, for-profit firms. The financial difficulties of

these plans created uncertainty for the roughly 1.8 million enrollees the plans

covered in Massachusetts at their peak and raised questions about the continuing

viability of locally owned, not-for-profit health plans. HPHC and Tufts lost their

position as market leaders as consumers switched to more stable health insurance

options.

HPHC’s severe financial difficulties

were exposed in late 1999, when the plan

unexpectedly posted a $226 million loss.

The state intervened swiftly, placing the

plan into receivership and thereby preventing

disruptions of care for consumers and

a much-feared acquisition by a national,

for-profit insurer. After restructuring the

plan’s debt and allowing certain accounting

changes, the state placed the plan under

administrative supervision and will continue

to monitor its financial status until 2002.

One of HPHC’s downfalls was its

attempt to expand regionally. Since 1999,

HPHC has withdrawn from neighboring

states and reduced its staff substantially. It

also has moved to bring costs under control

by adopting a three-tier pharmacy

benefit, capping Medicare prescription

drug coverage and investing in information

technology to improve its relationships

with providers and consumers. HPHC’s

turnaround efforts appear to be working,

and the plan posted a small operating profit

in the first quarter of 2001. HPHC lost

approximately 700,000 members as a result

of its withdrawal from other New England

states and declines in local membership,

however, and some observers question

whether growing costs will outpace the

plan’s declining revenue.

Tufts’ financial problems also were

associated with failed regional expansion

efforts. The plan posted a $42 million loss

in 1999 and responded, like HPHC, by

reducing staff and withdrawing from three

neighboring states. Although Tufts lost an

estimated 122,000 members and saw its

reserves decline significantly, the plan is

now considered relatively stable.

The financial woes of HPHC and Tufts

highlighted the limited authority policy makers

had to protect consumers from potentially

large-scale disruptions to care. In late

1999, the Massachusetts Legislature enacted

the HMO Insolvency Act, giving the state

Department of Insurance authority to take

over failing plans to ensure that enrollees

continue to receive health care services.

Community Hospitals Struggle. After struggling for more than a decade,

the financial health of Boston’s community hospitals also has deteriorated over

the last two years, leading two hospitals to close and threatening service reductions

and closures elsewhere. Community hospitals’ financial woes stem from a variety

of problems. First, as in many markets nationally, hospitals in Boston have faced

declining reimbursement from private and public payers, increasing labor and pharmaceutical

costs and losses from unsuccessful merger and physician integration strategies.

Second, patients’ growing preference for the Boston area’s prestigious AMCs-the

so-called flight to quality-reportedly has drained community hospitals’ patient

base and eroded essential revenue. According to the state, teaching hospitals’

share of total inpatient discharges in the Boston area grew from 34 percent in

1990 to 42 percent in 2000. Third, all hospitals are required by the state to

contribute resources to an uncompensated care pool, but many are not reimbursed

for the charity care they provide.

Hallmark Health, a struggling community hospital system in the northern Boston

suburbs, closed inpatient services at its 210-bed Malden campus in 1998 and announced

that it would close outpatient services there in 2001. Hallmark also announced

that, because of its financial difficulties, it would close Everett Whidden, a

121-bed facility in North Boston, this year. Other struggling community hospitals

included Symmes Hospital, a 111-bed freestanding community hospital also in a

northern Boston suburb, which closed in 1999; Quincy City Hospital, a 282-bed

hospital in a southern suburb, which announced in 1999 that it would close; and

a large Catholic community hospital system- Caritas Christi-which announced plans

to reduce services at three of its hospitals.

These actual and threatened hospital

closures raised new concerns about access

to care and costs in a market historically

noted for its excess hospital capacity. One

concern was that closures in particular

communities would limit access to care for

nearby residents, especially those unable to

travel. Another was that the growing phenomenon

of emergency room diversions

signaled the possibility of emerging inpatient

capacity constraints that would be

exacerbated by closures and service reductions.

Finally, there was concern that

community hospital closures and service

reductions could accelerate the trend

toward providing routine care in relatively

expensive AMCs.

After Malden and Symmes closed, the public outcry led policy makers and leaders

of local hospitals to save other endangered hospitals. Both the city and the state

intervened with financial assistance to save Quincy City Hospital. In addition,

Quincy entered into an affiliation with Boston Medical Center, a key safety net

hospital system, which allowed the community hospital to remain open, though at

reduced capacity. Cambridge Health Alliance, another major safety net hospital

system, stepped up to help maintain services at Everett Whidden and certain essential

outpatient services at Hallmark’s Malden campus, with the expectation that Cambridge’s

higher Medicare, Medicaid and state uncompensated care pool reimbursements would

help finance these services. Finally, state policy makers helped Caritas Christi

keep its hospital services intact by awarding the system approximately half of

the $10 million distressed hospital funds the state disbursed in 2000.

State policy makers have since taken

steps to ensure that there is greater community

say in reorganizing local health

care services by passing a law that requires

providers to notify the state and hold a

public hearing 90 days before closing

essential community services. Although it

is unclear how far the state might push to

prevent closures, the new law provides a

mechanism to demonstrate the potential

impact of a service cutback on the community

and makes the decision-making

process more transparent.

In addition, policy makers are

grappling with long-term solutions to

hospitals’ financial problems. One strategy

would involve increasing Medicaid reimbursement

rates to cover hospital costs

of care. A recent report commissioned by

the Legislature concluded that this would

cost $200 million annually. However,

some observers note that pressure on

Medicaid to address severe financial

problems in the state’s nursing home

industry may take precedence over payment

increases to hospitals. t the time of HSC’s 1998 site visit, Boston’s health care

market had reached relative equilibrium after multiple mergers and acquisitions

left the market consolidated largely around three locally operated, not-for-profit

health plans and two large academic medical center (AMC)-based provider systems.

Since then, a series of events has upset the fragile balance among these organizations,

threatening disruptions for consumers and prompting policy makers to intervene.

Leading Plans Falter. Two local, not-for-profit health plans with national

reputations as pioneering, high-quality HMOs-Harvard Pilgrim Health Care (HPHC)

and Tufts Health Plan-experienced serious financial problems. Both HPHC and Tufts

have long been a source of local pride. Their local roots and not-for- profit

status have been important features in the eyes of policy makers and local providers,

who have been wary of national, for-profit firms. The financial difficulties of

these plans created uncertainty for the roughly 1.8 million enrollees the plans

covered in Massachusetts at their peak and raised questions about the continuing

viability of locally owned, not-for-profit health plans. HPHC and Tufts lost their

position as market leaders as consumers switched to more stable health insurance

options.

HPHC’s severe financial difficulties

were exposed in late 1999, when the plan

unexpectedly posted a $226 million loss.

The state intervened swiftly, placing the

plan into receivership and thereby preventing

disruptions of care for consumers and

a much-feared acquisition by a national,

for-profit insurer. After restructuring the

plan’s debt and allowing certain accounting

changes, the state placed the plan under

administrative supervision and will continue

to monitor its financial status until 2002.

One of HPHC’s downfalls was its

attempt to expand regionally. Since 1999,

HPHC has withdrawn from neighboring

states and reduced its staff substantially. It

also has moved to bring costs under control

by adopting a three-tier pharmacy

benefit, capping Medicare prescription

drug coverage and investing in information

technology to improve its relationships

with providers and consumers. HPHC’s

turnaround efforts appear to be working,

and the plan posted a small operating profit

in the first quarter of 2001. HPHC lost

approximately 700,000 members as a result

of its withdrawal from other New England

states and declines in local membership,

however, and some observers question

whether growing costs will outpace the

plan’s declining revenue.

Tufts’ financial problems also were

associated with failed regional expansion

efforts. The plan posted a $42 million loss

in 1999 and responded, like HPHC, by

reducing staff and withdrawing from three

neighboring states. Although Tufts lost an

estimated 122,000 members and saw its

reserves decline significantly, the plan is

now considered relatively stable.

The financial woes of HPHC and Tufts

highlighted the limited authority policy makers

had to protect consumers from potentially

large-scale disruptions to care. In late

1999, the Massachusetts Legislature enacted

the HMO Insolvency Act, giving the state

Department of Insurance authority to take

over failing plans to ensure that enrollees

continue to receive health care services.

Community Hospitals Struggle. After struggling for more than a decade,

the financial health of Boston’s community hospitals also has deteriorated over

the last two years, leading two hospitals to close and threatening service reductions

and closures elsewhere. Community hospitals’ financial woes stem from a variety

of problems. First, as in many markets nationally, hospitals in Boston have faced

declining reimbursement from private and public payers, increasing labor and pharmaceutical

costs and losses from unsuccessful merger and physician integration strategies.

Second, patients’ growing preference for the Boston area’s prestigious AMCs-the

so-called flight to quality-reportedly has drained community hospitals’ patient

base and eroded essential revenue. According to the state, teaching hospitals’

share of total inpatient discharges in the Boston area grew from 34 percent in

1990 to 42 percent in 2000. Third, all hospitals are required by the state to

contribute resources to an uncompensated care pool, but many are not reimbursed

for the charity care they provide.

Hallmark Health, a struggling community hospital system in the northern Boston

suburbs, closed inpatient services at its 210-bed Malden campus in 1998 and announced

that it would close outpatient services there in 2001. Hallmark also announced

that, because of its financial difficulties, it would close Everett Whidden, a

121-bed facility in North Boston, this year. Other struggling community hospitals

included Symmes Hospital, a 111-bed freestanding community hospital also in a

northern Boston suburb, which closed in 1999; Quincy City Hospital, a 282-bed

hospital in a southern suburb, which announced in 1999 that it would close; and

a large Catholic community hospital system- Caritas Christi-which announced plans

to reduce services at three of its hospitals.

These actual and threatened hospital

closures raised new concerns about access

to care and costs in a market historically

noted for its excess hospital capacity. One

concern was that closures in particular

communities would limit access to care for

nearby residents, especially those unable to

travel. Another was that the growing phenomenon

of emergency room diversions

signaled the possibility of emerging inpatient

capacity constraints that would be

exacerbated by closures and service reductions.

Finally, there was concern that

community hospital closures and service

reductions could accelerate the trend

toward providing routine care in relatively

expensive AMCs.

After Malden and Symmes closed, the public outcry led policy makers and leaders

of local hospitals to save other endangered hospitals. Both the city and the state

intervened with financial assistance to save Quincy City Hospital. In addition,

Quincy entered into an affiliation with Boston Medical Center, a key safety net

hospital system, which allowed the community hospital to remain open, though at

reduced capacity. Cambridge Health Alliance, another major safety net hospital

system, stepped up to help maintain services at Everett Whidden and certain essential

outpatient services at Hallmark’s Malden campus, with the expectation that Cambridge’s

higher Medicare, Medicaid and state uncompensated care pool reimbursements would

help finance these services. Finally, state policy makers helped Caritas Christi

keep its hospital services intact by awarding the system approximately half of

the $10 million distressed hospital funds the state disbursed in 2000.

State policy makers have since taken

steps to ensure that there is greater community

say in reorganizing local health

care services by passing a law that requires

providers to notify the state and hold a

public hearing 90 days before closing

essential community services. Although it

is unclear how far the state might push to

prevent closures, the new law provides a

mechanism to demonstrate the potential

impact of a service cutback on the community

and makes the decision-making

process more transparent.

In addition, policy makers are

grappling with long-term solutions to

hospitals’ financial problems. One strategy

would involve increasing Medicaid reimbursement

rates to cover hospital costs

of care. A recent report commissioned by

the Legislature concluded that this would

cost $200 million annually. However,

some observers note that pressure on

Medicaid to address severe financial

problems in the state’s nursing home

industry may take precedence over payment

increases to hospitals.

Back to Top

AMCs’ Consolidation Strategies

Yield Mixed Results

evelopments among Boston’s premier

academic medical systems also caused

considerable turmoil in the market. In

the mid-1990s, many Boston AMCs

embarked on ambitious consolidation

strategies to shore up their positions and

withstand the expected growth of managed

care. For one system, consolidation has

caused serious financial strain, while for

another it has helped to tip the balance of

power away from health plans.

Some of the pitfalls of consolidation

for providers are illustrated by the experience

of CareGroup-a system created out

of the merger of two Harvard Medical

School teaching hospitals, Beth Israel and

New England Deaconess, and a federation

of five affiliated community hospitals. After

the now-combined Beth Israel Deaconess

implemented an ambitious consolidation

and integration strategy, it sustained operating

losses of $215 million over the past

two years and lost substantial market share

as dissatisfied physicians fled the system.

Beth Israel Deaconess hopes to improve its

position by bolstering profitable services

such as cardiology and oncology and pursuing

cost-cutting initiatives. However,

some observers fear that Beth Israel

Deaconess’ sharp financial decline could

have far-reaching effects on the CareGroup

system as a whole. In fact, one community

hospital, Deaconess Waltham, recently

announced the possibility of dropping out

of CareGroup-a move that may signal

substantial changes for the system.

In stark contrast, the experience of

Partners HealthCare illustrates the potential

benefits of consolidation for providers,

along with the potential downside for consumers.

Partners was created in 1994 with

the merger of two prestigious hospitals-

Massachusetts General and Brigham and

Women’s-and now also includes four

community hospitals and several affiliates.

Partners integrated services and facilities

slowly and used the strong affiliation of

member hospitals and 4,000 affiliated

physicians to strengthen its position in

managed care contract negotiations. This

strategy explicitly leveraged the strong

brand-name status of the system’s two

flagship hospitals, while building joint

bargaining power.

Over the past year, the success of this

strategy from the providers’ perspective

became clear, as Partners won payment

increases, reportedly as high as 25 to 30 percent,

from all three of the major local plans: evelopments among Boston’s premier

academic medical systems also caused

considerable turmoil in the market. In

the mid-1990s, many Boston AMCs

embarked on ambitious consolidation

strategies to shore up their positions and

withstand the expected growth of managed

care. For one system, consolidation has

caused serious financial strain, while for

another it has helped to tip the balance of

power away from health plans.

Some of the pitfalls of consolidation

for providers are illustrated by the experience

of CareGroup-a system created out

of the merger of two Harvard Medical

School teaching hospitals, Beth Israel and

New England Deaconess, and a federation

of five affiliated community hospitals. After

the now-combined Beth Israel Deaconess

implemented an ambitious consolidation

and integration strategy, it sustained operating

losses of $215 million over the past

two years and lost substantial market share

as dissatisfied physicians fled the system.

Beth Israel Deaconess hopes to improve its

position by bolstering profitable services

such as cardiology and oncology and pursuing

cost-cutting initiatives. However,

some observers fear that Beth Israel

Deaconess’ sharp financial decline could

have far-reaching effects on the CareGroup

system as a whole. In fact, one community

hospital, Deaconess Waltham, recently

announced the possibility of dropping out

of CareGroup-a move that may signal

substantial changes for the system.

In stark contrast, the experience of

Partners HealthCare illustrates the potential

benefits of consolidation for providers,

along with the potential downside for consumers.

Partners was created in 1994 with

the merger of two prestigious hospitals-

Massachusetts General and Brigham and

Women’s-and now also includes four

community hospitals and several affiliates.

Partners integrated services and facilities

slowly and used the strong affiliation of

member hospitals and 4,000 affiliated

physicians to strengthen its position in

managed care contract negotiations. This

strategy explicitly leveraged the strong

brand-name status of the system’s two

flagship hospitals, while building joint

bargaining power.

Over the past year, the success of this

strategy from the providers’ perspective

became clear, as Partners won payment

increases, reportedly as high as 25 to 30 percent,

from all three of the major local plans:

- Partners adopted an aggressive

negotiating strategy with Blue Cross Blue

Shield of Massachusetts. After six months

of talks, Blue Cross Blue Shield, rather

than risk losing its premier provider,

agreed to large reimbursement increases.

- Next, Partners turned to Tufts in late

2000, reportedly demanding close to a

30 percent reimbursement increase over

three years. After three months of unsuccessful

negotiations, Partners announced

it would not renew its contract and

advised its 100,000 patients covered by

Tufts to make other arrangements for

health care, threatening a major blow to

Tufts as its open-enrollment period

neared. Fearing disruptions for consumers,

the state attorney general and an

influential large employer urged the two

sides to resume negotiations. The dispute

was resolved nine days later, with Tufts

making significant concessions to Partners.

- Finally, Partners made its case to HPHC,

seeking a 28 percent payment increase

over four years. Although the state attorney

general weighed in again-this time

out of concern for the effect of rate

increases on the still-struggling health

plan-Partners again succeeded in securing

significant payment increases.

Partners’ success in winning substantial

payment increases from all three of the

major plans reflects a remarkable power

shift away from health plans. The system

contends that years of steep discounts from

health plans and reduced Medicare and

Medicaid revenue left them no choice but

to push back on commercial plan payment

rates. Health plans caution, however, that

increasing provider reimbursement will

accelerate the trend toward higher premiums.

From the consumer perspective,

Partners’ tactics have created instability

by threatening disruptions to care.

Back to Top

HMOs Undergo Extensive Change

acing new pressures from providers

and employers, health plans are exploring

innovative ways of managing care and controlling

costs. Risk arrangements have fallen

out of favor with providers, and health plans

have begun to experiment with new product

designs that can accommodate changing

market conditions. Quality improvement

initiatives have received added attention, in

part because of urging from local employers.

Boston has one of the highest HMO

penetration rates in the country, with nearly

50 percent of the population enrolled in

HMOs. Boston HMOs have broad and

overlapping provider networks, few restrictions

on services and rely on discounted

fee-for-service payment arrangements

with withholds contingent on providers’

meeting set utilization targets. Typically,

20 to 30 percent of provider organizations’

total annual compensation is at risk.

For various reasons, providers have not

fared well financially under these payment

arrangements, and some providers have

begun to resist them.

Approximately 29,000 Medicare beneficiaries

in Massachusetts had to switch

plans or select new physicians over the past

year because some providers were unwilling

to accept risk contracts for Medicare

products. Providers are also beginning to

push back on risk in commercial plan

products due in part to tensions over

payment levels and referrals, and many

observers believe this practice will become

widespread. Indeed-in what may prove

to be a harbinger of changes to come-

Partners’ recent contract with HPHC

eliminated withholds that were contingent

on providers’ utilization patterns, replacing

them with bonuses if certain quality standards

are met.

Boston’s employers, while accepting

double-digit premium increases, have

begun to demand patient safety initiatives

and care management programs. The state

employees’ purchasing coalition, which represents

82,000 employees and approximately

250,000 people (about two-thirds of whom

live in Boston), is an example. This coalition

adopted the standards of the Leapfrog

Group-a national organization that advocates

purchasing directives that promote

quality improvement-by including financial

penalties in its recent contracts for plans

failing to reach specified targets for reducing

medical errors. Other employers have urged

plans to supplement their own care management

strategies with programs developed

by national disease management companies

to see which approaches work best.

To help manage costs, plans have

adopted new product designs, including

a three-tier pharmacy benefit and higher

copayments for physician office visits.

Some plans also are exploring the possibility

of a three-tier hospital benefit in which

consumers would pay different amounts,

depending on where they received care. acing new pressures from providers

and employers, health plans are exploring

innovative ways of managing care and controlling

costs. Risk arrangements have fallen

out of favor with providers, and health plans

have begun to experiment with new product

designs that can accommodate changing

market conditions. Quality improvement

initiatives have received added attention, in

part because of urging from local employers.

Boston has one of the highest HMO

penetration rates in the country, with nearly

50 percent of the population enrolled in

HMOs. Boston HMOs have broad and

overlapping provider networks, few restrictions

on services and rely on discounted

fee-for-service payment arrangements

with withholds contingent on providers’

meeting set utilization targets. Typically,

20 to 30 percent of provider organizations’

total annual compensation is at risk.

For various reasons, providers have not

fared well financially under these payment

arrangements, and some providers have

begun to resist them.

Approximately 29,000 Medicare beneficiaries

in Massachusetts had to switch

plans or select new physicians over the past

year because some providers were unwilling

to accept risk contracts for Medicare

products. Providers are also beginning to

push back on risk in commercial plan

products due in part to tensions over

payment levels and referrals, and many

observers believe this practice will become

widespread. Indeed-in what may prove

to be a harbinger of changes to come-

Partners’ recent contract with HPHC

eliminated withholds that were contingent

on providers’ utilization patterns, replacing

them with bonuses if certain quality standards

are met.

Boston’s employers, while accepting

double-digit premium increases, have

begun to demand patient safety initiatives

and care management programs. The state

employees’ purchasing coalition, which represents

82,000 employees and approximately

250,000 people (about two-thirds of whom

live in Boston), is an example. This coalition

adopted the standards of the Leapfrog

Group-a national organization that advocates

purchasing directives that promote

quality improvement-by including financial

penalties in its recent contracts for plans

failing to reach specified targets for reducing

medical errors. Other employers have urged

plans to supplement their own care management

strategies with programs developed

by national disease management companies

to see which approaches work best.

To help manage costs, plans have

adopted new product designs, including

a three-tier pharmacy benefit and higher

copayments for physician office visits.

Some plans also are exploring the possibility

of a three-tier hospital benefit in which

consumers would pay different amounts,

depending on where they received care.

Back to Top

Universal Coverage Initiative

Fails but Prompts New Law

ealth care advocacy organizations in Massachusetts sponsored

a November 2000 state ballot initiative, known as Question 5, to require the Legislature

to enact universal health care coverage for state residents, and to prohibit for-profit

conversions of health care organizations and implement a patients’ bill of rights.

Plans and employers spent $5 million on an advertising campaign in a successful

effort to defeat the measure. The narrow margin of defeat for the initiative-52

to 48 percent-was viewed as an indication of residents’ continued strong support

for universal health care coverage.

In July 2000, with the ballot measure vote looming, the Legislature passed a long-debated

managed care reform law, known as Chapter 141. If voters had approved the November

2000 initiative, this law would have been superseded. Although Chapter 141 establishes

a commission to research options for universal coverage, the main focus of the

law is on patients’ rights. It calls for an external review process and various

other patient protections short of the right to sue health plans. In addition,

it includes provisions regulating plan-provider payment arrangements. Some observers

believe these payment provisions will dampen plans’ and providers’ willingness

to participate in risk arrangements. One of the most controversial provisions

of Chapter 141 is a requirement that plans send letters to enrollees to inform

them, not only of services that are denied coverage, but also of services that

are approved. Plans contend that this requirement is extremely costly and administratively

burdensome. ealth care advocacy organizations in Massachusetts sponsored

a November 2000 state ballot initiative, known as Question 5, to require the Legislature

to enact universal health care coverage for state residents, and to prohibit for-profit

conversions of health care organizations and implement a patients’ bill of rights.

Plans and employers spent $5 million on an advertising campaign in a successful

effort to defeat the measure. The narrow margin of defeat for the initiative-52

to 48 percent-was viewed as an indication of residents’ continued strong support

for universal health care coverage.

In July 2000, with the ballot measure vote looming, the Legislature passed a long-debated

managed care reform law, known as Chapter 141. If voters had approved the November

2000 initiative, this law would have been superseded. Although Chapter 141 establishes

a commission to research options for universal coverage, the main focus of the

law is on patients’ rights. It calls for an external review process and various

other patient protections short of the right to sue health plans. In addition,

it includes provisions regulating plan-provider payment arrangements. Some observers

believe these payment provisions will dampen plans’ and providers’ willingness

to participate in risk arrangements. One of the most controversial provisions

of Chapter 141 is a requirement that plans send letters to enrollees to inform

them, not only of services that are denied coverage, but also of services that

are approved. Plans contend that this requirement is extremely costly and administratively

burdensome.

Back to Top

Safety Net Strengthened

n contrast to mainstream providers and plans, Boston’s safety

net providers have been financially strong over the past two years, due in part

to continued state support and sound management strategies. Expansions in Medicaid

and the State Children’s Health Insurance Program and a strong economy also helped

to strengthen the safety net, causing the state’s uninsurance rate to drop considerably.

This trend may continue, given strong legislative support for raising the tobacco

tax an additional 50 cents per pack to extend Medicaid coverage further.

The two major safety net hospital

systems-Boston Medical Center and

Cambridge Health Alliance-continue to

receive the majority of the state’s uncompensated

care and Medicaid disproportionate

share hospital funds. In addition, each hospital

system’s Medicaid managed care plan

has grown because of Medicaid expansions

and entry into new markets outside Boston.

Indeed, the financial strength of these hospitals

was evident in their ability to step in

and help bolster the area’s struggling community

hospitals.

Community health centers (CHCs) in

Boston have become more financially stable

over the past two years, thanks to additional

state funding and new organizational and

management strategies. CHCs benefited

from more than $38 million in new state

funding, as well as increased Medicaid payment

rates for dental services. Although

the state’s largest CHC, East Boston

Neighborhood Health Center, declared

bankruptcy in 1999, it is recovering with

the help of federal and state aid and

improved fiscal management. Finally, some

CHCs have merged or formed alliances to

share overhead expenses and have established

relationships with hospital systems

to obtain assistance for capital improvements

such as information systems. n contrast to mainstream providers and plans, Boston’s safety

net providers have been financially strong over the past two years, due in part

to continued state support and sound management strategies. Expansions in Medicaid

and the State Children’s Health Insurance Program and a strong economy also helped

to strengthen the safety net, causing the state’s uninsurance rate to drop considerably.

This trend may continue, given strong legislative support for raising the tobacco

tax an additional 50 cents per pack to extend Medicaid coverage further.

The two major safety net hospital

systems-Boston Medical Center and

Cambridge Health Alliance-continue to

receive the majority of the state’s uncompensated

care and Medicaid disproportionate

share hospital funds. In addition, each hospital

system’s Medicaid managed care plan

has grown because of Medicaid expansions

and entry into new markets outside Boston.

Indeed, the financial strength of these hospitals

was evident in their ability to step in

and help bolster the area’s struggling community

hospitals.

Community health centers (CHCs) in

Boston have become more financially stable

over the past two years, thanks to additional

state funding and new organizational and

management strategies. CHCs benefited

from more than $38 million in new state

funding, as well as increased Medicaid payment

rates for dental services. Although

the state’s largest CHC, East Boston

Neighborhood Health Center, declared

bankruptcy in 1999, it is recovering with

the help of federal and state aid and

improved fiscal management. Finally, some

CHCs have merged or formed alliances to

share overhead expenses and have established

relationships with hospital systems

to obtain assistance for capital improvements

such as information systems.

Back to Top

Issues to Track

inancial difficulties among Boston’s health

plans and providers and contentious contract

disputes since 1998 have resulted in

higher premiums for employers and higher

out-of-pocket costs and increasing network

instability for consumers. HMOs have begun

to change considerably, and though use of

risk arrangements and tightly managed

products is waning, there is increased interest

in care management and quality improvement

activities that hold promise for the

future. As the Boston market continues to

evolve, several issues warrant tracking: inancial difficulties among Boston’s health

plans and providers and contentious contract

disputes since 1998 have resulted in

higher premiums for employers and higher

out-of-pocket costs and increasing network

instability for consumers. HMOs have begun

to change considerably, and though use of

risk arrangements and tightly managed

products is waning, there is increased interest

in care management and quality improvement

activities that hold promise for the

future. As the Boston market continues to

evolve, several issues warrant tracking:

- Will plans and community hospitals continue

to experience financial instability,

and, if so, what effects will this have on

the makeup of the health system and continuity

of care for consumers?

- Will threats of care disruption from

health plan-provider contract disputes

become a routine phenomenon in the

Boston health care market, and, if so,

what will the impact be on costs and

consumers’ access to care?

- How will employers respond to rising

premiums, and what effect will their

response have on health plan products?

- Will the state be able to maintain its high

levels of care and coverage for low-income

uninsured despite a potentially

slowing economy?

Back to Top

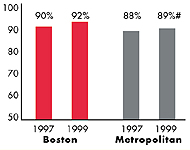

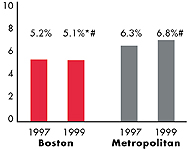

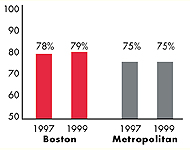

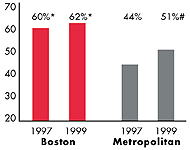

Boston’s Experience with the Local Health System, 1997 and 1999

Back to Top

Background and Observations

| Boston Demographics |

| Boston County |

Metropolitan areas above 200,000 population |

Population, July 1, 19991

4,409,572 |

| Population Change, 1990-19992

|

| 2.8% |

8.6% |

| Median Income3 |

| $31,868 |

$27,843 |

| Persons Living in Poverty3 |

| 10% |

14% |

| Persons Age 65 or Older3 |

| 14% |

11% |

Sources:

1. US Bureau of Census, 1999 Community Population Estimates

2. US Bureau of Census, 1990 & 1999 Community Population Estimates

3. Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1998-1999 |

| Health Insurance Status |

| Boston |

Metropolitan areas above 200,000 population |

| Persons under Age 65 with No Health Insurance1 |

| 8.1% |

15% |

| Children under Age 18 with No Health Insurance1

|

| 3.0% |

11% |

| Employees Working for Private Firms that

Offer Coverage2 |

| 88% |

84% |

| Average Monthly Premium for Self-Only Coverage

under Employer-Sponsored Insurance2 |

| $198 |

$181 |

Sources:

1. Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1998-1999

2. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Employer Health Insurance Survey, 1997 |

| Health System Characteristics |

| Boston |

Metropolitan areas above 200,000 population |

| Staffed Hospital Beds per 1,000 Population1

|

| 2.7 |

2.8 |

| Physicians per 1,000 Population2

|

| 3.3 |

2.3 |

| HMO Penetration, 19973 |

| 46% |

32% |

| HMO Penetration, 19994 |

| 48% |

36% |

Sources:

1. American Hospital Association, 1998

2. Area Resource File, 1998 (includes nonfederal, patient care physicians,

except radiologists, pathologists and anesthesiologists)

3. InterStudy Competitive Edge 8.1

4. InterStudy Competitive Edge 10.1 |

Back to Top

The Community Tracking Study, the major effort of the Center for Studying Health

System Change (HSC), tracks changes in the health system in 60 sites that are

representative of the nation. Every two years, HSC conducts surveys in all 60

communities and site visits in 12 communities. The Community Report series documents

the findings from the third round of site visits. Analyses based on site visit

and survey data from the Community Tracking Study are published by HSC in Issue

Briefs, Data Bulletins and peer-reviewed journals. These publications are

available at www.hschange.org.

Authors of the Boston Community Report:

Kelly J. Devers, HSC

Jon B. Christianson, University of Minnesota

Laurie E. Felland, HSC

Sue Felt-Lisk, Mathematica Policy Research, Inc.

Liza S. Rudell, HSC

Linda R. Brewster, HSC

Ha T. Tu, HSC

Community Reports are published by HSC:

President: Paul B. Ginsburg

Director of Site Visits: Cara S. Lesser

Director of Public Affairs: Ann C. Greiner

Editor: The Stein Group

|